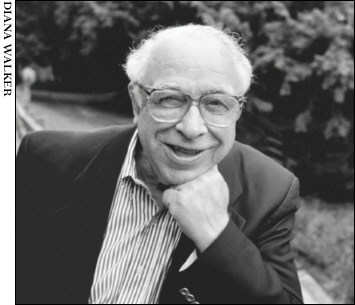

ART BUCHWALD

“People are constantly amazed when I tell them I was a Marine.”

IT’S HARD TO IMAGINE a greater contrast to Ben Bradlee’s family, Harvard education, wartime service, dashing appearance, and general rakishness than his old friend Art Buchwald, the lovably teddy-bear humorist and columnist who may have been the most unlikely Marine in all of World War II. In his autobiography Leaving Home, he wrote with endearing candor, “People are constantly amazed when I tell them I was a Marine. For some reason, I don’t look like one—and I certainly don’t act like one. But I was, and according to God or the tradition of the Corps, I will always be a Marine.”

At seventeen, Buchwald was running from a troubled childhood and the heartbreak of a failed summer romance. He persuaded a street drunk to forge his father’s signature on the permission form needed to enlist in the Marine Corps. That he survived basic training on Parris Island was a minor miracle. He was always in a jam for his bumbling ways, terrorized by his drill instructor, Corporal Pete Bonardi of Elmhurst, Long Island.

Buchwald spent the war in the South Pacific, attached to a Marine ordnance outfit, loading ammunition onto the Marine Corsairs that were dueling with Japanese Zeroes in the skies over places like Guadalcanal, Okinawa, and Midway. He was on a tiny island called Engebi.

Buchwald was not much more competent on Engebi than he had been at Parris Island. Loading a large bomb onto a Corsair, he hit the wrong lever and it dropped onto the tarmac, sending his buddies scattering, convinced they were about to be blown up. Finally Buchwald’s sergeant assigned him to work on the squadron’s mimeographed newsletter and to drive a truck, reasoning he couldn’t do much harm to himself or others in those jobs. His sergeant told him later, “You had the ability to screw up a two-car funeral. Anything you touched ceased to function.”

He also learned more than he wanted to know about anti-Semitism. Many of the small-town boys he served with had never known a Jew, and they were quick to repeat the bigotry of their upbringing. Buchwald, much more a man of wit and words than fists, nonetheless found himself in numerous fights after some reference to a “kike” or “Christ-killer.” But then he decided it wasn’t worth all the anger and bruises, so he just responded “Stuff it” and walked away. Now, on reflection, he says, “I can’t maintain people picked on me just because I was Jewish. They picked on me because I was an asshole”—followed by that familiar Buchwald laugh.

Buchwald’s life after the war began at the University of Southern California, where he enrolled under the GI Bill even though he didn’t have a high school diploma. In the crush of veterans registering in 1946, the admissions office simply didn’t check. By the time he was found out, Buchwald was a fixture on campus and accepted as a special student.

At USC, Buchwald began to hone the gentle, mocking style of humor that would make him one of journalism’s best-known columnists and a high-priced public speaker. He wrote for the campus newspaper and a humor magazine. He was friendly on campus with Frank Gifford, the All-America football hero; David Wolper, later one of Hollywood’s most successful producers; and Pierre Cossette, who became the man behind the televised Grammy Awards. It was a fantasy come true for this funny little man from a succession of foster homes in New York.

His Walter Mitty life took an even more romantic turn when he learned the GI Bill was good in Paris as well as in the United States. Determined to become another Hemingway or Fitzgerald, Buchwald hitchhiked to New York and caught an old troop ship for France. He lived the life of an expatriate on the modest stipend the GI Bill provided him for classes at the Alliance Française, drinking Pernod late into the night in Montparnasse, stringing for Daily Variety back in the States, and hanging out with new friends who would later become famous writers: William Styron, Peter Matthiessen, James Baldwin, Mary McCarthy, Irwin Shaw, and Peter Stone. As he recounted in I’ll Always Have Paris, Buchwald loved the life. “We had come out of the war with great optimism,” he said. “It was a glorious period.”

Art Buchwald

It became even more glorious when Buchwald talked himself into a job at the glamorous International Herald Tribune, the English-language newspaper that was distributed throughout Europe and served as a piece of home for American tourists. In 1949, just seven years after he’d been rejected by his summertime sweetheart and joined the Marines in a desperate attempt to find a new life, Art Buchwald had talked his way into one of the most sought-after jobs in journalism. “Paris After Dark,” Buchwald’s column, quickly became one of the most popular items in the paper, and it led to the byline humor column that made him the best-known American in Paris. He was the city’s most popular tourist guide for visiting stars such as Frank Sinatra, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, and Audrey Hepburn.

His books became bestsellers, and when he came home, sixteen years later, he was an even bigger star in Washington, with his own table at the most popular restaurant in the capital and lecture fees now at five figures, often with a private plane for transportation. His was practically an uncle to the various Kennedy offspring. When he went to Redskins games, he sat in the owner’s box. He summered on Martha’s Vineyard with pals Katharine Graham, Mike Wallace, Bill Styron, and Walter Cronkite.

However glamorous his life had become, he never forgot he was a Marine. When Colin Powell was preparing to leave the military and enter civilian life, Buchwald offered to advise him on what lecture agencies would serve him best. Powell’s assistant called Buchwald, inviting him to lunch with the general at the Pentagon. Buchwald said, “Lunch? Don’t I get a parade? I was in the Marine Corps three and a half years and I never had a parade.” When Buchwald arrived at Powell’s office, the general said, “Follow me.” He took Buchwald into a large room where Powell had assembled fifty of his staff. As Buchwald entered, they all came to attention and gave him a salute. After all those years of people not believing he had been a Marine, Buchwald had a parade, with the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs at his side, in the Pentagon.

He laughs now when he thinks of how much attention he received from Marine brass once he moved to Washington. “They said I was a great Marine. I was a lousy Marine. But at the last Marine Ball I attended, colonels were coming up to have their pictures taken with me. I loved that.”

Buchwald’s feelings go well beyond the attention he gets at Marine ceremonies. “I had no father to speak of, no mother. I didn’t know what I was doing. Suddenly I’m in the Marines and it’s my family—someone cared about me, someone loved me. That’s what I still feel today.”

Despite his lovably rumpled appearance, Buchwald also maintains certain habits he learned at Parris Island. He keeps his personal effects neatly arranged, just as he did in his footlocker during basic training. His shoes are always shined to a high gloss. He always has an extra pair of socks, just as the Marines taught him.

During the Vietnam War, he was caught between conflicting emotions. He was against the war, yet when the Marine Corps asked him to record some radio commercials for their recruiting efforts he happily complied. He was flattered, in fact; after all, he was a Marine. He realized that his old loyalties and his current thinking were in conflict only when friends began to point out the inconsistencies of his behavior. He stopped recording the commercials.

Buchwald has written about his Marine Corps experience so often that fellow leathernecks often approach him to compare notes, inevitably saying, “You think your drill instructor was tough. Mine was the toughest in the Corps.” Buchwald never concedes. He knows Pete Bonardi was the toughest.

In 1965, Life magazine asked Buchwald to return to Parris Island for a week of basic training, to recall the old days. He agreed, if he could take along his old drill instructor, Pete Bonardi.

He found Bonardi working as a security guard at the World’s Fair in New York and arranged for him to get the time off work. Bonardi remembered Buchwald from basic training, saying, “I was sure you’d get killed,” adding warmly, “You were a real shitbird.”

In his book, Buchwald recalls that they had a nostalgic week at Parris Island and that nothing much had changed. He may have been famous, but he was still a klutz. On the obstacle course, Bonardi was still yelling things like “Twenty-five years ago I would have hung your testicles from that tree.” At the end of the week, they shook hands and parted friends.

A quarter century later, Buchwald received a call from a mutual friend telling him Bonardi was gravely ill with cancer. Buchwald telephoned his old drill instructor, whose voice was weak as he told Buchwald he didn’t think he could make this obstacle course.

In Leaving Home, Buchwald describes taking a photo from their Life layout and sending it to Bonardi with the inscription “To Pete Bonardi, who made a man out of me. I’ll never forget you.” Bonardi’s wife later told Buchwald that the old D.I. had put the picture up in his hospital room so everyone could read it.

Bonardi also had one final request. That autographed picture from the shitbird, the screw-up Marine he was sure would be killed, little Artie, the guy he called “Brooklyn” as he tried to make a leatherneck out of him? Corporal Bonardi, the toughest guy Buchwald ever met, asked that the picture be placed in his casket when he was buried.

I confess that I weep almost every time I read that account, for it so encapsulates the bonds within that generation that last a lifetime. For all of their differences, Art Buchwald and Pete Bonardi were joined in a noble cause and an elite corps, each in his own way enriching the life of the other. Their common ground went well beyond the obstacle course at Parris Island.