THE ARENA

“Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed, to a new generation of Americans, born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace.”

—From John F. Kennedy’s inaugural speech, January 1961

Given the ambitions of his father and family, John Kennedy’s decision to pursue a public life was not wholly altruistic, but in his eloquent inaugural speech he gave voice to his generation on the issues of peace and war, and also on the importance of entering the arena beyond the battlefield. In the postwar years, politics was a noble calling and a natural extension of the lives of the men and women who had made so many sacrifices and learned so many lessons during the war. Their ideologies and their ambitions spanned a broad spectrum, but they came to the public arena determined to have their say in the future of the country and of the world.

Some, such as Wisconsin senator Joe McCarthy, a tail gunner in the Marine Corps during the war, emerged with a dark and twisted view of what was necessary to advance the cause of liberty. Others drew entirely different lessons from their common experiences. John Kennedy, the scion of a rich and powerful Boston family, a decorated Navy veteran, ran as a Democrat against Republican Richard Nixon, also a Navy veteran, the son of a poor Quaker family from California. Senators Barry Goldwater and George McGovern were both pilots from western states during the war, and when they landed in the U.S. Senate they were at opposite ends of the political field. Strom Thurmond and Ernest “Fritz” Hollings, both World War II veterans, represent the same state, South Carolina, in the U.S. Senate. They’re equally colorful and canny, politicians with Old South manners and rich accents, but one is a Republican and the other a Democrat.

From Eisenhower through George Bush, all but one American president was a veteran of World War II. The exception was Jimmy Carter, a Naval Academy graduate who was commissioned as an officer just as the war ended. From the fifties through the seventies, the halls of Congress were dominated by World War II veterans. Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois, a classic liberal, had been a lieutenant colonel in the Marine Corps. Senators Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, George McGovern of South Dakota, Edmund Muskie of Maine, Jacob Javits and Daniel Patrick Moynihan of NewYork, Warren Magnuson of Washington, George Smathers of Florida, John Tower of Texas, John Glenn of Ohio, Mark Hatfield of Oregon, Frank Church of Idaho—all World War II veterans.

State capitols were the fiefdoms of governors such as Orville Freeman in Minnesota, who still carried a prominent scar on his jaw from a gunshot wound he’d received while serving in the Marines. Governor John Connally of Texas saw considerable action in the Pacific with the Navy, but his most serious wounds came when he was riding in a limousine with fellow Navy veteran John Kennedy on November 22, 1963. William Scranton, governor of Pennsylvania, was a World War II pilot. Governor Harold Hughes of Iowa was an Army infantryman. George Wallace was a defiant symbol of segregation as governor of Alabama, but he had a notable combat record as a crewman on Army Air Corps bombers in the Pacific.

They came out of the same war to their political posts, but they were not in lockstep in their ideologies. Their varied views on social, diplomatic, and military questions were another affirmation of the independence and skepticism that Andy Rooney so admired when they were men in uniform. They emerged from the war with those qualities intact and reenforced. They took them to the political arena along with their hard-won understanding that the world is a large and complicated place, a personal self-confidence gained in the most trying circumstances, and their determination to influence the fate of their time.

They were immediately faced with a new war, a Cold War that would go on for forty years and threaten the entire world with nuclear destruction of a far greater magnitude than Hiroshima or Nagasaki. An ally turned foe, Joseph Stalin, had a voracious appetite for power and a nuclear arsenal to back it up. The day he died in 1953, a refugee from eastern Europe living in our South Dakota community said to my mother, “They’re stoking it up down below for old Joe today.”

Stalin had galvanized the West into forming a new military alliance, NATO. China under Mao Zedong and communism set off a wave of other fears, leading to another shooting war, this one on the Korean peninsula.

Then there were the unresolved issues at home, particularly of race and broader economic opportunity. There were great public-works projects to construct. The men and women of this generation moved from the problems of war to the problems of peace with alacrity. They were not always correct in their approach, but they were not intimidated. They also had a deeply personal understanding of the consequences of war as an instrument of national policy. They were the young men another generation of old men had sent to war. Now they had in their hands those same decisions for another generation of young Americans, this time in Vietnam.

The Vietnam War deeply divided not only the country but the World War II generation as well. The leading hawks and some of the most eloquent doves were from that generation. The new war also created a cultural schism. Those in political life who publicly supported the war effort while wrestling with private doubts had a visceral antipathy for the long hair, language, and flag-burning ways of the antiwar demonstrators. Then, too, they knew that in the working-class neighborhoods and on the farms, there were no deferments and little access to alternative service.

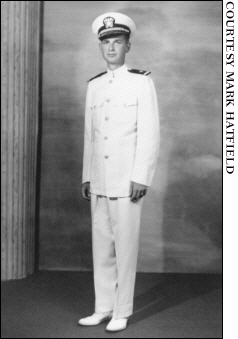

No two politicians symbolized the differences with greater clarity than two friends in the U.S. Senate, both members of the Republican party: Bob Dole of Russell, Kansas, and Mark Hatfield of Salem, Oregon. One the son of a small-town jack-of-all-trades, the other the son of a railroad blacksmith. One an infantry lieutenant, the other a Navy ensign.

Mark Hatfield