7. Nitrogen and the Forgotten Fourth Starter

The first job that I ever had was selling baseball cards. My father’s assistant manager at the parking garage had a side business selling cardboard on weekends. He needed someone who could do enough math to make change and who didn’t mind sitting around thinking and talking about baseball all day. I was 10 and to this day, it was the greatest job I ever had.

This was during the early 1990s, a period of time now known among card collectors as the “junk wax” era, but we didn’t think of it that way back then. Baseball cards had been produced even in the 1800s, but it wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s that baseball cards came into their own. Before the 1950s, most sets were one-off, small-batch collections that featured well-known, All-Star-level players, and were meant to be prizes that would help to sell cigarettes or chewing gum. In 1952, Topps—a chewing gum company—tried something different. They issued a set of 407 cards, including the now-iconic Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays rookie cards. It was the largest set of baseball cards ever made by a country mile. It also flipped the sales model upside down. Topps sold the cards in packs of five and the chewing gum was the nice little prize. A few decades later, they stopped bothering to include the gum.

By the 1980s, the kids of the 1950s had grown into adults who had developed the most universal disease of adulthood, nostalgia. Those who had been card collectors in their youth began reaching back for pieces of their childhood, only to find that few of those baseball cards had survived, mostly by hiding in attics for 30 years. As tends to happen, the number of nostalgic adults exceeded the number of attics and the forces of economics took over. Prices for old cards began to climb, as the first generation that had grown up with card collecting as a hobby grew into adults who had incomes capable of supporting the chase to hold a few extra moments of youth in their hands.

The high prices that baseball cards were fetching drew plenty of newcomers to the business. In 1981, Topps, after functionally having a monopoly on baseball cards for a few decades, was joined by upstarts Fleer and Donruss. Score and Upper Deck cards would appear a few years later, all of the companies producing sets of several hundred cards and all hoping that not only could they sell cards to baseball-loving kids, but that serious adults would see the cards as an investment. What resulted was a spectacular crash, and like every other crash in history, it seems obvious in hindsight, though we missed it (or chose to ignore it) when it was happening in front of us. The market massively overproduced inventory to the point that cards from that era can now be had for the cost of shipping them. Thankfully, I wasn’t an investor back then. I was a kid who was just happy to open a couple of packs.

The 1952 Topps set is normally discussed in terms of the Mantle and Mays rookie cards, which continue to fetch six-digit prices on the open market, but I’d propose that the most important card in the bunch actually belonged to Willie Ramsdell. (He was listed on the card by his given middle name of Willard.) In 1951, “Willie the Knuck”—Ramsdell was a knuckleballer—had gone 9–17 pitching 196 entirely forgettable innings for the Cincinnati Reds. For his efforts, he was traded to the Chicago Cubs before the 1952 season. After 67 innings as a Cub, he fell out of Major League Baseball, never to return again. Because of the rarity of the 1952 set, Ramsdell’s card still fetches a few dollars, but it’s likely that most of the people reading this book have no idea who Willie Ramsdell is. That’s the point.

Ramsdell was the fourth starter on a team that had finished the 1951 season with a 66–86 record in the 18th largest city in the United States, and yet he was deemed worthy of enshrinement in cardboard and specks of bubble gum–scented sugar dust. Whether the Topps Company specifically planned it or not, their decision reflected—or maybe spurred—a major breakthrough in how fans thought about baseball. With a set of 407 cards, and only 16 teams in Major League Baseball at the time, it meant that Topps was producing cards for more than 20 players on each team. No longer were cards reserved for famous names like Yogi Berra and Warren Spahn, who would have been well-known even outside their hometown fan base. There was room for just about everyone. This was a strategic risk for Topps. There were plenty of serious baseball fans who wouldn’t have recognized Willie Ramsdell on the street, even if he was in uniform. It meant the distinct possibility that fans might plunk down their hard-earned nickels for a pack of baseball cards, only to discover that all five were obscure role-players on teams that they’d never seen play.

A somewhat less charitable interpretation of the Ramsdell gambit might have been that Topps was hoping to use the principles of gambling in their sales strategy. If every pack had a Stan Musial or a Ralph Kiner in it, then someone buying a pack would have the thrill of nabbing an All-Star every time they opened one. Topps may have been trying to space out the “good” cards with cards that they knew that few would care about. It would reduce the number of times that the card buyer had the thrill of encountering an All-Star, but it would make them chase that high by spacing out that reward at random intervals, rather than satisfying that itch every time. Topps essentially turned the experience of buying otherwise worthless pieces of cardboard into something resembling a slot machine.

Whether Topps was priming nine-year-olds with their first taste of casino action or whether they simply thought that the public had a right to know Ramsdell’s 1951 stats and his place of birth (and before the internet, where else could one find this information?) the cards slowly became collector’s items. Sure, Mantle and Mays would fetch higher prices than Ramsdell, but soon, people were collecting sets of baseball cards. It was as important to have Ramsdell as Mantle. The set was not complete without both.

A set of baseball cards is a tangible collection of baseball in its entirety at some moment in time. All (well, most) of the players who played regularly in 1951 are in that set, from the superstars to the backup catchers, each with his own eight-and-three-quarters square inches of cardboard real estate. Collecting cards of individual players is a cult of personality. Collecting the set is to savor the game itself. It’s a philosophical statement. There are no unimportant parts of baseball, there are just parts that get more attention than others. If you take any of those parts away, even the little parts that don’t seem to do much, it stops being a set. It stops being baseball.

For baseball junkies, Willie Ramsdell is like nitrogen gas, which comprises nearly 80 percent of the air we breathe in, even though the body doesn’t actually use it. We simply breathe it back out. Yet that gas fills the entirety of every space that we occupy in life. It’s easy to dismiss nitrogen (or Ramsdell) as unimportant, but chemically, nitrogen gas is a stable compound and without it the atmosphere would be far less stable. That atmosphere keeps us alive even if we’re only interested in the 20 percent that’s oxygen—or Willie Mays. Mays wouldn’t be there without the Willie Ramsdells of the world to pitch to him.

I caught the baseball-card bug early in life, thanks to my parents. For Christmas when I was seven, they got me a full 1986 Topps set. I still have it. When I got it, it was already in an album, arranged uncreatively in order from card number 1 in the set to number 792. Players from different teams were strewn about the pages with no rhyme or reason other than whatever logic (if any) Topps put in to numbering their cards. I had to hunt to find pictures of my beloved Cleveland Indians. While baseball cards are social objects that facilitate friendships among children (I traded cards with the best of them), they also have an awesome one-player mode. I felt the need to bring order to the chaos that was the seemingly random assignment of one through 792. So, much to my mother’s horror, all 792 cards came out of their sleeves and onto my bedroom floor. I decided to organize them.

At first, I organized the players by team, but that seemed so banal once I was done with it. Out they came again onto my floor.

This time, I decided to alphabetize the players. Orioles pitcher Don Aase was happy for a while; Braves shortstop Paul Zuvella was not, but eventually I grew tired of alphabetical order and decided to sort the players by position. (Sorry, Mom.) The 1986 Topps set had a little circle on the front of the card with the player’s preferred position printed in it. Most players had just one position listed, but I was struck by the fact that some players had two. At the time, it didn’t occur to me that these were largely interchangeable utility infielders. I figured that they must be some sort of special super-athlete to play both second base and shortstop. They got their own section of the album, and I still have a strange affinity for utility infielders.

That’s the beauty of baseball minutiae. It’s a game full of nooks and crannies and the occasional rabbit hole. There are thousands of little pieces of information about the game. Some of them are more important than others, or perhaps it’s better to say that some are more appreciated than others. Sometimes, even if something isn’t all that important, it’s still fun to understand how it works.

That 1986 Topps set taught seven-year-old me classification and sorting skills in a way that no schoolbook could ever teach. Reorganizing my baseball cards was the first time that I ever played around (literally!) in a data set, and something fun happens when you start playing around in any data set. You start noticing patterns and asking questions that begin with “Why…?”

I remember being struck by the fact that there were so many “SS-2Bs” and not a lot of “OF-3Bs” and wondering why that was. The answer to that question might not be important to understanding the game, but it planted the seeds of exploration in my head. The fact that this book exists can be traced back to that same sense of wonder.

I probably would have kept going with my reorganization of those 1986 cards, finding different ways to group the players together, but eventually the 1987 set ended up under the Christmas tree. My 1986 set is still in a closet at my house, sorted by position, and once in a while it still feels good to pull out that album and breathe in that air from when I was seven. There’s the nitrogen, the oxygen, the nostalgia, the curiosity about utility infielders, and Andy McGaffigan, the Cincinnati Reds’ fourth starter that year.

* * *

I’ve never caught a foul ball. I’ve been to a couple of games where I was in the right section, but I never got a chance to make a play on a batted ball off the bat of a major leaguer, even if it was one that went the wrong way. Once, when I was 10 or 11, I was sitting at the end of a row in the lower deck of Cleveland Municipal Stadium when a member of the Minnesota Twins lined a ball foul off to the side, directly up the aisle-way. (Thankfully, no one was in the way!) The ball ricocheted off the facing of one of the concrete stairs that led to the concourse and it bounded back down the aisle where it landed on the step one row behind me. I jumped to snare the pearl but was beaten to it by about half a second by a guy in his thirties. Had I been a few years younger, I might have been more spry, or perhaps I could have pulled the “cute kid” trick and the guy might have given me the ball. Alas, the ultimate baseball raffle prize has never fallen from the sky into my outstretched hand.

Most baseball fans see foul balls as a source of souvenirs. To catch one is to take home a tangible piece of the game that you went to see. From a gameplay perspective though, foul balls are annoying. They don’t really do anything. With two strikes, they don’t even move the count along. They are just a null space in which a pitch was thrown, but nothing technically happened. What could possibly be worth looking in to about foul balls?

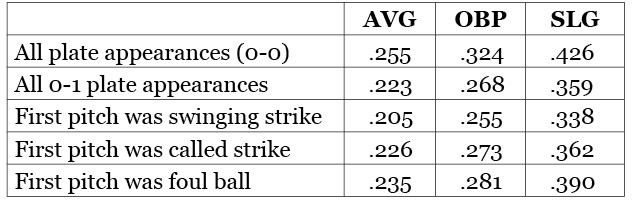

Foul balls may not move the game along, but they do contain information. We know that the batter swung and we know that he didn’t miss. Below we have numbers from 2017 showing what happens when a plate appearance starts out with a 0-1 count.

Table 39. Outcomes on 0-1 Counts, Non-Pitchers Batting, 2017

We can see that a first-pitch strike is not a great outcome for a batter, but we also see that it matters how that strike got there. A foul ball gets better results than a called strike, and both get much better results than a swinging strike. The fact that the batter didn’t miss tells us something, even if he didn’t hit the ball in the right direction. These findings even hold when we statistically control for the overall quality of the batter and pitcher. This means that even if we had the same batter and pitcher, but three different plate appearances, one starting with a called strike, one with a swinging strike, and one with a foul ball, we would still expect the same basic pattern of outcomes.

Let’s look at two-strike foul balls.

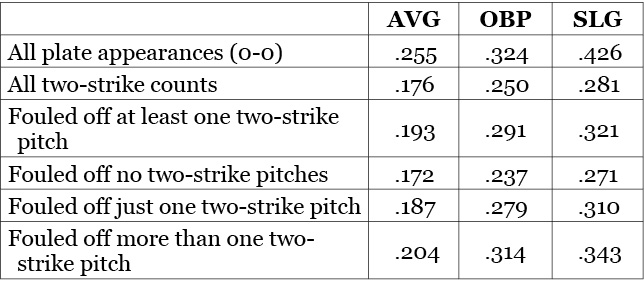

Table 40. Outcomes on Two-Strike Counts, Non-Pitchers Batting, 2017

Again, we see that a two-strike count is a bad idea for a hitter, but they do happen. In fact, in 2017, more than half of all plate appearances got to two strikes. A batter who fouled off a ball when he got to a two-strike count actually gets somewhat better results than we might otherwise expect. (Again, these findings hold even when we control for batter and pitcher quality.) Intuitively, this makes sense. The more two-strike pitches that a batter spoils, the more he forces the pitcher to labor and the more chances he gives the pitcher to make a mistake.

This isn’t the kind of value that people tend to look for in a baseball player, but it’s value. Even batters who foul a two-strike pitch off are hitting well below the league average, because they are, by definition, dealing with a two-strike count. We might look at the slash line of .193/.291/.321 and wonder who would want that? Someone who was stuck in a situation where the expected slash line is .172/.237/.271, that’s who. If a hitter is good at generating foul balls, he’ll be better able to cut his losses in a bad situation. Added value, even if it’s just taking things from “very bad” to merely “bad,” is still added value.

And you thought that they were just souvenirs!

* * *

A runner stands at first or, to be more precise, a few feet away from first. A pitcher turns and throws over to the first baseman and the runner takes a couple steps back to the bag. The first baseman throws the ball back, and the runner takes a few steps back off. Everyone knows what’s going on. In 2017, there were 16,721 throws made to first base to “check in” on a runner. A measly 1.5 percent of them resulted in a pick-off. There were another 0.7 percent of those throws where the pitcher threw the ball away allowing the runner to advance. That means that 98 percent of the time, a throw to first doesn’t “do anything” other than make the fans a little more antsy in their seats. Everyone knows that it doesn’t make much difference, but it happens anyway. It’s baseball’s way for the pitcher to say to the runner, “I haven’t forgotten about you.” Maybe it’s his way of saying, “I know what you’re thinking about…” Maybe there’s more going on there than meets the eye.

In 2017, the runners who most often got a “check in” were Delino DeShields Jr. (64 percent of the time he was on first), A.J. Pollock (61 percent), Trea Turner (60 percent), Byron Buxton (59 percent), and Jonathan Villar (59 percent). On the other side of that list, no one bothered at all to check in on Kendrys Morales or Victor Martinez in 2017. Salvador Perez, Nelson Cruz, and Joe Mauer all got throws over less than 3 percent of the times that they stood at first. I’ll let the reader figure out the pattern there.

Surprisingly, throws to first don’t act as a deterrent to runners trying to steal. Using data from 2013 to 2017, we can isolate all situations in which a runner was standing on first with second base open. We know that some runners like to try to steal more than others, so we’ll need to statistically control for that, as well as for some other factors that we know affect whether runners try to swipe a bag (the number of outs, the inning, whether the score is close). But even once we do that, we see that when a pitcher makes a throw over to first, the runner is actually more likely to try for second later in that at-bat than we might otherwise expect.

There are a couple of reasonable explanations for why this happens, none of which we can directly prove. One would be the “challenge theory,” which says that a runner might see the throw from the pitcher as a challenge. (“Oh…you think I’m going to run? I’ll show you.”) In Chapter 3, we talked about how managers are more likely to try to send a runner after having one caught stealing. Perhaps the same dynamic is playing out here. The other possibility is that pitchers can recognize situations when runners are more likely to make a break for it, and while they can’t stop a runner from trying, they can at least throw over and make him stay a tiny bit closer to the bag.

While a throw to first doesn’t deter runners from trying for second, it does have an effect on whether a runner makes it to second safely. Again, when we control for all of the same factors above, including how successful a runner usually is in his steal attempts, we find that when a pitcher has thrown to first, a would-be thief is less likely to be successful, by about 6 percentage points, controlling for everything else. That’s a pretty big effect. Reducing a runner’s chances of stealing by 6 percent is worth .04 runs of expected value to the defense. That might not seem like much, but it just takes a nice soft toss over to first to reach out and grab those runs.

Runners commonly take a lead of a few feet off first. Eventually, a stolen base comes down to a race between how quickly the runner can traverse the 90 feet between first base and second and how quickly the pitcher and catcher can get the ball to the second baseman. By getting a lead, the runner is trying to move the odds in his favor by shaving a few feet off his journey. A fast—but not blazing fast—runner might be able to average 20 feet per second on the bases. So, for every two feet—less than the average length of a step—closer to first base that the pitcher can make him stand, the runner will need roughly an extra tenth of a second to make it to second base. Those tenths of a second matter. The pitch-catch-throw-tag sequence usually takes around 3.4 or 3.5 seconds from the moment the pitcher releases the ball, so an extra tenth of a second is 3 percent of the time that the runner has available to make his mad dash.

A runner on first can’t stray too far off first base, lest he get picked off. Logically, he should choose the distance that is the furthest he can get away from the base while still feeling comfortable that he can get back if he needs to. Pitchers know that runners will be picking a distance that they are fairly sure is safe, and that actually recording a pickoff is rare, yet they throw over anyway. Why bother? It’s because the pitcher knows that the runner is human and humans have a tendency to overcorrect.

If a runner was able to make it back to first with a lead of 10 feet, then he should be able to do it again. After all, he just did it. That’s not what the human mind does though. By throwing over to first, the pitcher has put the thought into the runner’s head that he can (and will) throw over. Of course, the runner already knew that, but now that thought is front and center in his mind. It might mean that he takes a slightly shorter lead or hesitates just the tiniest fraction of a second more when trying to decide if the pitcher really is going to throw home this time. In a cat-and-mouse game where there are less than four seconds to get away from the cat, those fractions can be the difference between a stolen base and a caught stealing. The data suggest that this is exactly what happens.

The real reason that a pitcher throws over isn’t that he thinks he’ll pick the runner off. If that happens, it’s a nice bonus, but he’s really playing a mind game with the runner. The prize he’s going for is that extra half-step that no one notices.

* * *

In 2017, Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred made what looked to be a minor change to the rules of the game. The intentional walk, long a staple of strategy in the game, would be no more—at least the part where the pitcher throws four purposefully wide pitches so that everyone can pretend that this is an actual at-bat. Instead, the manager was allowed to signal to the umpire for an intentional walk, and the batter could just trot down to first.

Strangely, my defense of the “classic” intentional walk—the one where you have to actually throw four balls—begins with the center fielder, but first, we need to meditate on the absurdity of the center fielder, a man standing 300 feet from the spot where the action is. In most other sports, it isn’t even physically possible to have a defender that far away. Three hundred feet can fit the length of three basketball courts and one-and-a-half hockey rinks. Three hundred feet marks off the distance from end zone to end zone in football. In baseball, a 300-foot fly ball is rather pedestrian. There’s even more real estate out there beyond the center fielder. A baseball field is a very large place.

That has some consequences. It means that a good number of the seats in the ballpark are also several hundred feet away from the place where the ball is launched. Unlike soccer or basketball where the location of the action moves around the playing surface—which means that at different times, seats will be closer to or further away from the game action—the batter’s box doesn’t move. It means that the two most important people in any at-bat—the pitcher and the batter—are confined to only a few square feet worth of space, 60 feet, six inches apart, and 500 feet away from the guy who paid $12 to sit in the center-field bleachers.

Baseball looks very different when watched at close range. I remember clearly the first time that, when I was in high school, my friends and I snuck down into the lower reserve section at Jacobs Field and watched half an inning from the first row behind the backstop. (Even my teenage rebellions involved baseball.) Eventually, an usher politely asked us to remove ourselves from that area, lest we be removed from the park, but I remember it well. The pitches moved. It wasn’t video game movement. They still obeyed the laws of physics, but they moved. And the batter muttered. And the pitcher danced. There was emotion coming from all of the participants after each of those pitches. It was its own little soap opera.

For most of my life, when I had gone to a baseball game, I sat in those $12 seats. I knew that the outcome of a pitch, whether ball or strike, was important, but I mostly considered it important because I knew that a strike brought the batter closer to a strikeout and a ball brought the batter closer to a walk. All you can really see from center field is the ball being thrown down the chute and the umpire making a call.

There’s a lot of action that goes on between the pitcher and hitter on all of the pitches. It shows up a lot better on television than in the bleachers. The center-field camera gives a decent perspective on the ball’s movement and the body language of the pitcher and batter after each pitch, so I knew some of what was going on. The thing is that there once was a time when baseball games were not shown on television. That might not seem like a big deal, but it means that baseball spent a great deal of its early existence where there were only two ways to experience the game. One was on the radio (once it was invented) and the other was in person, probably sitting a few hundred feet from the batter’s box.

* * *

Baseball is a game played in two parts. There’s the dance of the batter and pitcher and then there’s what happens at the end of that dance when (and if) the batter hits the ball. Much of the first part of that dance is played out in the realm of inches. Plenty of pitchers live either just on the corner of home plate or just off of it. The difference between a “good” slider and a bad one might be a couple inches of break. It’s the sort of resolution that even the best human eye can’t get from a few hundred feet away. From that distance, they all look the same. But a fly ball hit in the air 300 feet from the batter’s box? That was easy enough to see.

That too had consequences. In baseball’s formative years, a language grew up around the end of the dance. Hitters “singled” or “grounded to third” or “flied out to center field.” From this language, there came forth numbers that became culturally important, almost all of them based on summarizing what had happened at the end of a player’s turn in the box. Batting average summarizes the outcome of a hitter’s at-bats. On-base percentage summarizes the outcome of a hitter’s plate appearances. Home runs are a specific outcome that can end a turn at the dish. So are strikeouts.

Baseball’s culture grew to speak of its heroes in terms of how their plate appearances ended. There’s nothing wrong with that. That is eventually the object of the game, but what would have happened if baseball had built all of its ballparks with all of its seats behind home plate, close enough to watch the dance of the slider? What if Abraham Lincoln himself could have turned on the television to watch a game? What if a language had developed where we talked about both Babe Ruth’s career home run total, and also the number of pitches just off the corner that he was able to lay off?

But alas, that never happened. The physics of the game called for a center fielder and seats that were too far away to fully appreciate that batter-pitcher tango. By the time radio and television were widespread, baseball already had an entire language, poetic and numerical, that it used to talk about itself. The fundamental assumption of that language was that what happened at the end of the at-bat was what mattered, with special preference given to things that the fans could see from the stands. Television might be able to show the movement of the pitches, but by the time television came around, there were few words to describe how pitch movement affected the game and the fans watching at home didn’t grow up speaking them.

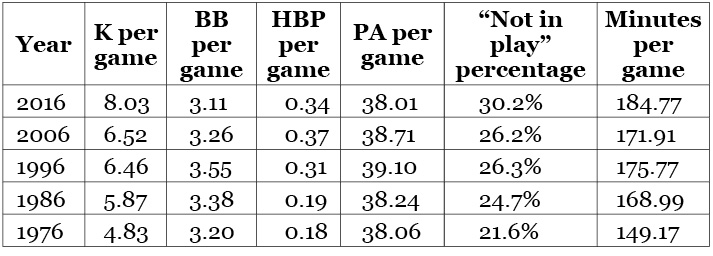

Table 41. “Not in Play” Events per Game per Team, 1976–2016

Major League Baseball took a look at these data before the 2017 season and decided that it had a problem. Games had grown noticeably longer, by more than half an hour over the course of 40 years, despite the fact that patrons still got to see almost the exact same number of hitters come to the plate. There’s another trend that has walked alongside that increase. Driven almost entirely by an increase in strikeouts, hitters were putting the ball in play a lot less than they used to. Over 40 years, the number of plate appearances ending with a “not in play” event jumped by almost 10 percent.

The issue of game length and game pace are separate, though related problems, and baseball has never been clear on which one it’s trying to solve. Maybe the answer is “both.” The game has grown up with a clear cultural preference for the ball being hit into play, but it has also evolved past seeing strikeouts as a moral failing as it once did. (Karma did not punish Casey for his hubris by having him ground to third.) Instead, strikeouts are now seen as an unfortunate, though bearable side effect of behaviors that teams do like. Power hitters strike out a lot, but they also hit a lot of home runs. Whatever their moral valence, strikeouts are hard to appreciate from 500 feet away, and even though television can show the anguished face of the batter after he flails at the forbidden candy that he shouldn’t have chased, we are still programmed to associate “action” with “hitting the ball.”

This left MLB in a strange position. They couldn’t command teams to strike out less. They did what they could, instituting suggestions, like requiring the batter to keep one foot in the batter’s box, even when he was adjusting his batting gloves. If they couldn’t induce more balls in play, they could at least say, “C’mon guys, let’s get this over with.”

The psychologist in me sympathizes with the gentlemen who are on the field taking an extra moment before stepping into place. Baseball is a game of sustained attention in a low-stimulation environment under conditions of sleep deprivation. Baseball is a game where most of the time nothing happens, but you have to pay close attention anyway because when something does happen, you have to react quickly. That’s hard to do when the team plane landed at 3:00 am last night.

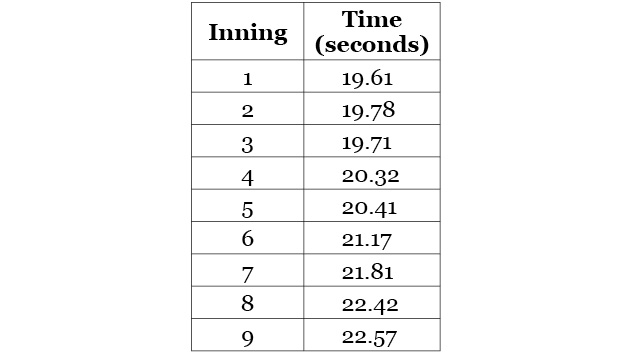

Table 42. Length of Time Between Pitches, by Inning, 2017

(Note: bases empty only)

As the game wears on, things start taking just a bit longer. That makes sense. When people in laboratory settings are asked to perform a sustained attention task without rest, their reaction time slows as the task gets longer and they have more lapses in attention. It’s not surprising if hitters take an extra moment to reset their focus before climbing into the batter’s box to face a 98 mph fastball that could literally kill them. MLB could legislate that they not take those extra moments, but they’d be legislating against the realities of neuropsychology. Their reward would be players who aren’t quite on their game.

Here we need to ask again whether the cure is worse than the disease. Yes, games could be shorter, but there wouldn’t be quite as much thrill from seeing some of the hemisphere’s best athletes playing a game at the highest possible level that it can be played. There are going to be days when the score is 8–3 and the eventual outcome of the game isn’t much of a mystery, but in any one plate appearance a player can make a highlight reel–worthy catch or hit a home run that breaks the tape measure. Even if the game is a dud, the fans can at least go home talking about that play. Take away those little extra pauses and you take away some of the player’s abilities to generate those moments. It’s like cutting a few minutes off Swan Lake by sending in the junior varsity ballet dancers, because they pirouette a little faster.

* * *

When I worked as a therapist, it was important to understand not only the problem that a person was bringing to the therapy room but why they believed that it was a problem. In baseball’s case, they have identified the clock as the problem. For a business which makes its money by selling an entertainment product, it’s a perfectly reasonable fear to have, but MLB has a fear of being boring. Like anything else, boring is in the eye of the beholder, though MLB has a business interest in making sure that as many eyes as possible are beholding the game.

I rather like spending three-and-a-half hours at the ballpark, but even I recognize that an 8–3 snoozer is no one’s idea of a good time. And yet, while baseball complains about long games and extended pauses, they sure do sell those moments when it suits them. Watch the television feed of a close game and you are guaranteed to see close-ups of a reliever as sweat drips down his face and he takes a deep breath before shaking off his catcher. The batter takes an extra moment before stepping in and has a determinedly placid look on his face as he wiggles his bat a little bit. Back to the pitcher, who comes set as the crowd noise swells behind them both, and then…the batter calls time. Baseball can be such a tease.

Suddenly, in a close game, the very issue that baseball had declared as the reason for boredom is now a dramatic moment, despite the fact that “nothing” is happening. Now the pause is a reason to love the game. It’s a reason to luxuriate in the fact that the game is in the balance and might be won by the heroes or the villains, and we have no idea who. It’s an invitation to become emotionally invested. It’s the setup for what is often called a “Hollywood ending.”

I’d argue that baseball doesn’t have a time-of-game problem. It has a narrative-pacing problem. It wants to tell a good story. To solve it, maybe baseball can take a few lessons from another art form: film. Filmmakers don’t tell a story in the most efficient way possible, because humans don’t perceive stories in terms of efficiency. Instead, film uses a complicated visual language all its own that we often don’t even recognize, but one that conforms to the way that people absorb narratives. When a scene opens, the filmmaker rarely jumps right to the action, but instead leaves an “establishing shot” on the screen for a few seconds. If the characters will be interacting at a diner, the screen will show that diner from the outside. The establishing shot doesn’t actually move the plot along, but the brain needs a moment to transition from the last scene where they were in a laundromat. Or a spaceship. Or Mount Rushmore.

Filmmakers also play around with time in their composition. It’s a standard film technique to use slow-motion footage during a particularly important moment in the film. Efficiency would be showing the event at full speed, which is how things actually proceed, but it’s not how humans experience big events. When people experience crisis moments in real life, they will often recall the event by saying, “It’s as if time slowed down.” It didn’t, but there’s a very real cognitive reason why it seems that way. During normal operations, the human brain has millions of pieces of information that it could pay attention to. The problem is bandwidth and capacity. To pay attention to every single detail all the time would be maddening.

Instead, the brain is predisposed to pay attention to certain bits of information, process others on auto-pilot, and ignore others. In a crisis situation, as the brain realizes that this is an important moment, it begins collecting as much data as it can for this short burst. We are used to a certain amount of information representing a certain amount of time, but the brain’s short-term information-gathering binge messes with that ratio. Filmmakers have learned to use that to their advantage, mirroring the brain’s natural tendency to slow things down as a signal to the viewer. Pay attention. This scene is really important.

The intentional walk is a counterintuitive strategy. The pitcher is not supposed to want the batter to reach base, and yet there he is doing something that will guarantee the batter does. This must be an extraordinary moment if they are resorting to doing something that they aren’t supposed to. The intentional walk is most often placed at an important juncture in the game, and like a filmmaker who is trying to set a good narrative pace, the IBB slows the game down and allows a bit of time for baseball’s version of an establishing shot as we watch two grown men play catch exactly four times. The whole process used to take a minute or so in the good old days when you actually had to throw the pitches, and now we can shave most of that minute off the game. But at what cost? Yes, we could get rid of that establishing shot and it would cut a little bit of time off of the movie, but would the movie actually be better for it?

I think there’s value in the “classic” intentional walk. We need those four pitches because they are part of the unspoken, visual language of the game. As the narrative of the game unfolds, the seconds that those four sham pitches consume actually serve a purpose in making the game fit with how humans process information, and therefore making the game more engaging. It’s not realistic to expect that a non-obsessed fan will watch every pitch of a game, especially one that doesn’t have much drama in it. It might even be a little much to ask the obsessed ones to do it. The rules of basketball and football provide for “action,” with the rules scheduling it on a regular and predictable basis. Baseball suffers from an unpredictability problem in that sense. To be a baseball fan is to have no idea when the next bit of “action” might be.

So I say bring back ball four. Make the pitcher actually issue an intentional walk, rather than just point the batter to first. Leave alone the language which baseball has evolved to work around some of its own limitations. Yes, they might seem like four useless lobs, but they do a job that’s much more important than just allowing the batter a free pass to first. And they’re worth the 45 seconds that it takes to make them happen.

* * *

The high school you went to turns over its entire student population every four years. The teachers who were there when you were 16 eventually move on to other jobs or retire. Yet, even though most of the people are gone, there is a connecting thread that somehow still makes the school feel familiar. At my high school, the cafeteria still smells like tater tots and 300 adolescent boys crammed into a small space. Somehow that part never changes. When I went to school there, I never really stopped to notice that smell. It took me time being an outsider before I realized how much that smell comprised the atmosphere that I breathed on a daily basis. It took even longer before I realized how much breathing that air shaped me as a person.

When Rob Manfred proposed the rule change concerning the intentional walk, there were plenty of strong reactions. That seems to happen any time baseball proposes a rule change, even something tiny and seemingly irrelevant. In the case of the intentional-walk rule, even the people who were against the change expressed frustration with their difficulty in explaining why they were even upset over something that meant so little. One day, when I was back visiting my high school, I had the same sort of reaction when I saw that they had replaced all of the old hallway lockers, including my locker. Sure, it had trouble closing half the time and probably should have been replaced 10 years before I got to the school. It wasn’t even really mine, given that plenty of other students had used it before and since I graduated, but it represented an object that linked me back to another time in my life. Yes, the school and its walls were still there and there was still a (new, impostor!) locker in that space, and yet I felt a profound sense of sadness about the loss of a malfunctioning piece of metal. When something is important to your life, there aren’t any unimportant parts. Maybe intellectually, there’s a case to be made that the new lockers or the new intentional-walk rule is measurably better, but emotionally, it stung.

When you grow up to be an obsessive baseball junkie like I did, you start to notice the little things and they become a part of you. I find baseball captivating because it provides so many opportunities to look at these seemingly small pieces of life and to recognize what a big impact they can end up having. Change one and the entire game—or your entire self—can change. What might seem irrelevant, like the nitrogen gas that we breathe in and breathe right back out, turns out to have a profound effect that few bothered to notice. There aren’t any unimportant pieces. There are just pieces that we haven’t yet given their proper attention.