In September 1999, I began my sophomore year at Kenyon College. I was part of a campus Christian group and had done some work organizing a welcoming committee for the new kids on campus. Through that work, I had gotten to know a couple of first-year students in the incoming Class of 2003. One of them mentioned that he and several other people would be hanging out later that night in Room 315 of McBride Residence Hall. “Come by whenever,” he said. That night, when I got to Room 315, I happened to sit down (perhaps not accidentally) near a tall, gorgeous Russian woman. Her name was Tanya and she remains the most interesting person I have ever met.

She was born in Moscow, but had moved to Atlanta when she was 11. We started talking in 315 and later in the exit stairwell that, at two in the morning, led a very smitten 19-year-old me down to the path back to my dorm. She thought my nerdy jokes were funny. She didn’t know anything about baseball, but we ended up bonding over babysitting. My summer job in college was working at a day care center, and she had spent the previous summer babysitting two little girls who were six and two. A few years later, they were the flower girls in our wedding, but we’re getting ahead of the story.

At first, we were just two people. I’d see Tanya around campus quite a bit. Kenyon was a small school in the middle of nowhere Ohio. It’s hard not to run in to someone, even if you’re trying to avoid them, and I didn’t mind running in to her. We had several friends in common, we ate breakfast around the same time, and she was fun to hang out with. In February of each year, the school held an annual formal dance for everyone on campus. The school’s founder was an Episcopal bishop named Philander Chase, so the dance was Philander’s Phebruary Phling, and that year, it phell on Valentine’s Day.

Phling was supposed to be the highlight of the Kenyon social calendar, although I had gone the year before and it was mostly just the same people I saw in class, obscenely drunk and dancing in the dining hall. In formalwear.

A few days before Phling, Tanya sent me an instant message (hello, 2000!) asking if I was planning to go. This was silly because everyone knew that everyone went to Phling. It was really the only thing to do on campus that weekend, but Tanya had something in mind. She said that she had always wanted to go to a formal dance wearing a suit and with her date in a dress. She had asked a few of her friends from her hall, and none of them would take her up on the idea. Then, she thought to ask me. I typed back two words that changed the entire course of my life. “Why not?” Thankfully, she had a dress that fit me “well enough.” We told no one of our plans and simply showed up together. That night the legend of Tanya-and-Russell was born.

Except that we weren’t dating. We were that couple, the ones who are the last two people in the world who realize that they are dating each other. By this point, we were regularly having breakfast together. Over the next summer, we wrote each other letters (on paper!) and I even called her on her birthday to sing the birthday song. My mother likes to tell the story of the next September, when everyone was getting back to campus for the new school year. After a summer apart, I saw Tanya and ran over to her and at the same time, she saw me and ran toward me. My mother told me several years later that in that moment, she had turned to my father and said, “Explain to me again how they’re not dating.” We weren’t. Really.

Well, by that point we were having breakfast together, usually lunch, and most of the time, dinner. We would rent kids movies on VHS (hello again, 2000!) from the Village Market and watch them together. We would study together in the library even though we were in completely different majors, because we were nerds. Sometime in October, one of our mutual friends asked, “Is it just me or does everyone think you two are dating?” We swore that we weren’t. Tanya was my friend with whom I just happened to spend nearly every waking hour. It wasn’t until that December that we admitted to ourselves that we were dating. We were apparently not the most aware people in the world.

There’s a beautiful and subtle vocal shift that takes place when any serious romantic relationship forms, and it took place in ours. We became Tanya-and-Russell. Yes, we were still two people, but we also formed a unit that was somehow more than just the two of us. I started noticing that when friends said our names, they ran them together a lot more closely than they did when they spoke the names of any two other people in sequence. Tanya and I had a deep discussion about this one night. She’d noticed it too. She notices things like that. It’s something I love about her.

The word “couple” is often used to refer collectively to people in romantic relationships, but I think there’s a relationship status that’s more than a “couple.” It’s the one where you get the hyphens and the ever-so-shorter pauses between your names, because the two of you are more than just two people now. Those are the good relationships. Tanya told me after we “started” dating that if we made it to three weeks together, we would probably end up getting married. Like most things in life, she was right.

In May of 2002, I graduated from Kenyon, but Tanya still had her senior year left. I moved to Chicago to start graduate school, which meant that we had a year of a long-distance relationship ahead of us. This time though, I didn’t miss the obvious cue when she started talking about graduate programs in the Windy City. For my part, I spent a lot of weekends that year on U.S. Route 30, which runs through the middle of rural Indiana and nowhere Ohio, driving back to Kenyon to see the woman whose name and soul had become intertwined with mine. In June of 2004, I dropped to one knee and asked Tanya to make those hyphens permanent. She said yes.

* * *

I was not an art major. Kind of like my dreams of being a major leaguer, my artistic abilities peaked in fourth grade, when the art class assignments went beyond pasting construction paper shapes on top of each other in some prespecified order. However, I was and still am handy with the collage, which is the big-kid version of pasting shapes on top of each other. The important task is to get all of the important stuff onto the page. How it’s arranged is secondary.

I think there’s a common assumption that baseball teams are put together the same way. Just put 25 really good players onto the approved list and you’ll be fine. It doesn’t matter whether they fit together or not. It’s one of those things that seems intuitively true. Of course, a team with 25 All-Stars has a better shot than a team with 25 guys who all belong in Triple-A. Talent is a huge part of the game; but is that all there is?

There is a concept in science known as emergence or emergent behavior, which is better known as the whole of an organism being greater than the sum of its parts. Human consciousness itself is an emergent property. The fact that you are currently awake and aware cannot be fully explained by the physical structures of the human brain, and yet here you are reading this book. Emergence can be a wonderful thing. It can take two goofy, nerdy college students and make them a couple. The problem with emergence is that it isn’t always good. It can take a group of people and make them an angry mob. Worse, it can make them do The Wave.

We are hardwired to see emergence in ways that we don’t fully appreciate. A series of small lights next to each other on a marquee that flash in a serial sequence become a set of “moving” lights. There is, of course, no motion, nor would the brain perceive them as “moving” if they were to flash in a random sequence, but by the way that they interact with each other, they become something more than just blinking lights. When talking about baseball, people often discuss players who “play together as a team.” A lineup where the “pieces complement each other.” A clubhouse where good chemistry is said to be the driving force behind a surprising run toward a playoff spot. Is it possible that in baseball, there are ways for a team to be more than the sum of its parts?

For baseball fans, it can be a fun game to play “pick the perfect team,” although it can quickly turn sour when you realize that it’s just a game of “recite last year’s All-Star roster” or “which inner-circle Hall of Famers do I have a strange fascination with?” Sure, your team of All-Stars would be better than any team currently playing, but this is not actually a team-building exercise. It’s like having nine separate discussions. One about the best first baseman in the league, followed by a discussion of the best second baseman, and on and on.

I recommend a different challenge. Let’s play “pick the-perfect-team” (with hyphens!). Imagine that for some reason, Major League Baseball has hired you and 29 other folks to helm each of the 30 teams. On top of that, MLB has just declared everyone a free agent! You get to start from scratch and your job is to put together a team that will win the World Series. There’s always a catch, though. As a condition of your getting this dream job, you have agreed to be bopped on the head (MLB will provide some aspirin, if you like) and have your knowledge of the actual players in Major League Baseball erased. You retain the knowledge that there are infielders and outfielders and starters and relievers and good players and bad players and all-hit-no-glove-players and no-hit-all-glove players. Thankfully, MLB is willing to bop you on the head again and restore your knowledge, but only after you submit a plan detailing how you will go about your job.

While we’re at it, let’s pay some amount of respect to the realities of team construction. You’ll need to actually find 25 guys and you’ll be given a salary limit. If you sign Mike Trout to a mega-deal, it will probably mean no mega-deal for Bryce Harper, even though it would be so much fun to see the two of them in the same outfield. You do, however, have the freedom to sign any 25 players in any configuration that you like. With that in mind, what would be your strategy? Would it still be “grab the best 25 players available”?

* * *

Writing in the Harvard Business Review in 2015, author Roger L. Martin laid out an astonishingly simple business maxim that can provide us a great deal of guidance here: “If the opposite of your core strategy choices looks stupid, then every competitor is going to have more or less the exact same strategy as you.” In his article, Martin lamented the fact that in the world of mutual fund management, many firms had stated that one of their key strategies was “great customer service.” At first this seems reasonable, because no business would survive if they provided poor customer service, but it’s also not a strategy. It’s a goal. No one would ever choose the opposite.

A real strategy forces you to make choices between options when it’s not obvious what the answer is. In other words, a strategic choice is one where you might be wrong. Providing good customer service is a reasonable goal, but should our mutual fund company do so by hiring more account managers (which will cost them more money) so that each manager has a smaller caseload and more time per client to provide customer service? Should they not hire as many, leaving account managers with bigger caseloads, but saving on salary and benefits? How big can a caseload get before customer service suffers? If it does, how likely are customers to start taking their business elsewhere? I don’t know the answer to any of these questions so I will use a phrase which means “I have no idea, but I still want to sound smart.”

It depends.

I love “It depends” because it has the benefit of being a true statement that tells us absolutely nothing. It’s true because the answer to just about every question in life really does depend on several complicated factors. If the answer were easy and obvious, then we wouldn’t have asked the question in the first place. “It depends” tells us nothing unless it’s followed by an answer to “On what?” Otherwise, “It depends” is mostly just a culturally acceptable way of saying “It’s complicated and I have no idea.” It’s always telling to see what things a culture is unwilling to admit out loud to the point where they must create a code phrase.

If I’m going to do something other than guess, I need to know a few things. What do we know about our customers? Are they willing to pay more for an account manager who is more dedicated to their specific needs? Will they really take their business elsewhere if they don’t get a call back within five minutes? Could we push our average time to 10 minutes? What’s the company’s current budget situation? If I knew the answer to those questions, I would be able to render a more qualified opinion (or any opinion at all), but the truth is that everything I know about mutual fund management can be written on the back of a dime with a crayon. If I want to answer this question, I’m going to have to dive in to the complexity to figure it all out. I will need real deep knowledge. I will need to know how all the parts work together.

Ah, but why do all the hard work of obtaining deep knowledge and understanding complexity when you can instead have a slogan! “Cut costs at all costs!” has the benefit of being easy to repeat, easy to follow, and sometimes might even be the right answer, or at least the right direction. Sentences with some variant of the word “always” in them are nice for the fact that they require minimal thought. Politicians love slogans. The engineer, on the other hand, answers questions like these often with complicated discussions about the details. Details are boring, but they run the world.

Baseball is full of cheap slogans too, some of which have even acquired enough mold to be considered wisdom. You can never have enough pitching! Defense wins championships! Power in the corners, speed up the middle! It’s true that I’d rather have plenty of pitching than not enough, but at some point, I might want to sign a hitter or two, especially if I already have 24 pitchers on my roster.

* * *

There are two ways to build value on a baseball team. One is to have better players. This is hardly revolutionary and immediately fails the Martin Test, but there’s always room for being able to identify what makes a player “better” in ways that competitors do not see. In Chapter 2, we saw that in the early part of the 2010s, only a few teams appeared aware of the effect that catcher framing could have in providing value to a team, but those who did snapped up the catchers who were good at it, and benefitted from the extra talent that no one else saw. Eventually though, when the league caught on to the catcher framing effect, the market simply began pricing that value into the cost of a catcher’s contract. It’s hard to keep a secret in baseball.

I’m much more interested in the second way that a team can build value, which is value generated through understanding how players fit together within the structure known as a baseball team. I’m interested in going beyond the parts and engineering a better way for those parts to work together. I’m interested in emergence. Unfortunately, emergence is another one of those concepts for which we lack words in baseball. We are used to assigning credit for events to an individual player (“Barry Bonds hit 73 home runs in 2001”), but what happens when two players interact with one another to create value?

For example, if a team has a fantastic set of defensively skilled infielders, a pitcher who induces a lot of ground balls will be worth more than that same pitcher in front of a more average group of fielders. The pitcher hasn’t changed, but he gets better results in front of the Gold Glovers. The Gold Glovers get to shine ever brighter when they play behind a pitcher who feeds them more ground balls. The team clearly benefits by generating more outs on defense, but to whom should we give the credit? The real fun of the “build the-perfect-team” game isn’t in the final roster. I’d submit that the game is actually at its best when it serves as a way to have a deeper discussion about the guts of how baseball works.

Let’s begin with the one advantage that we have been given in this exercise. We know that everyone is a free agent. That’s helpful because it means that we don’t have to make decisions about our team based on the fact that we already have 17 guys signed and we’re pretty much stuck with them. It also means that we can try some new things. We’ve been given carte blanche to construct a team in any way we prefer. It has to function as a baseball team over 162 games, but perhaps we can move away from the tyranny of how rosters are currently constructed and try a few new ideas. Most people would begin this exercise by assuming that we will need five starters, a few garbage-time relievers, a right-handed specialist, a left-handed specialist, a set-up man, and a closer, and then eight position player starters, a spare catcher, a couple of utility infielders and outfielders, and maybe a designated hitter. Perhaps we could even rethink whether those categories make sense. Not only have we cleared the roster, but we can destroy and rebuild its scaffolding if we want. We have total freedom on this canvas.

Let’s use it!

* * *

One of the most telling pieces of information about baseball is that teams may employ 25 people on a given day, with nine of them playing at any one time. Half of those roster spots are routinely dedicated to staffing just one of those positions, with the other half used to staff the remaining eight. The pitcher is the most important person on the field, because no matter what else happens, he is the only player who is guaranteed to touch the ball during a play.

We will begin with a simple multiplication problem. Over 162 nine-inning games, a team will need to have enough pitching to cover 1,458 innings. Some of those innings will be in games where the score is already 10–2, and some will be the ninth inning of a one-run game. There will be days where the game will go 16 innings. There will be days when we don’t need to bother with the ninth inning. Even more fun, a team goes to the ballpark every day having no idea which one of those will happen. A manager has to be ready for anything and there is probably going to be a game tomorrow night to think about as well.

It’s also telling that baseball games are often subtitled by the names of the two starting pitchers (“It’s Kershaw vs. Bumgarner! And oh yeah, the Dodgers are playing the Giants.”). In fact, if a sportscaster gives any information about a forthcoming game other than the time it starts, it’s almost exclusively the names of the two starters. It’s for good reason. If the pitcher is the most important person on the field, then the pitcher who figures to be out there for the majority of the game would be the most important player on his team for that game.

Major League teams routinely carry five starting pitchers, and hope that they go six to seven innings in each game. I call this the 5-6-7 rotation. These five starters are generally backed up by a squadron of six to eight relievers who most commonly throw one inning at a time. (In 2017, 51 percent of relief appearances were cases where the reliever got exactly three outs.) Therefore, most teams follow the 5-6-7-1-1-1 model when filling out the pitching side of the roster.

Of course, it wasn’t always this way. There was a time in baseball history where teams routinely used a four-man rotation and, while contrary to popular belief, the majority of starts did not take place on three days’ rest.

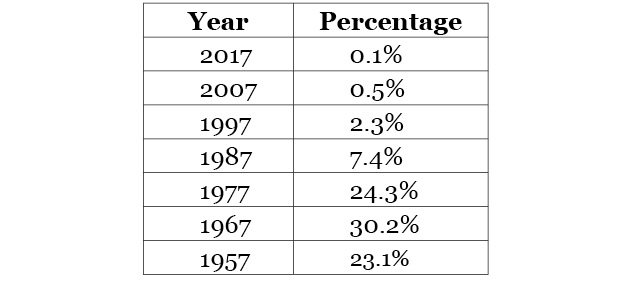

Table 9. Percentage of Regular Season Starts Made on Three Days’ Rest

There are those who long for the days of the four-man rotation, for the simple reason that it’s hard to find five good starters. Why not make the task 20 percent easier? Research that I have done suggests that this is not likely to happen. While we don’t have reliable injury information for pitchers going back into the 1950s and 1960s, we can use playing time data to find pitchers who were pitching for an extended period of time and then seemed to disappear for a while. Using a statistical technique known as Cox regression, I found that when I limited my data set to only the 1950s, the number of times that a pitcher started on three days’ rest actually predicted a lower risk of one of these “mysterious disappearances.” This was also the case in the 1960s.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the link broke, with pitchers who had a lot of starts on three days’ rest being no more or less likely to have one of these absences. By the 1990s and 2000s, the effect was clearly pointing toward starters who had three days of rest more often suffering more “injuries.” The decreased use of three days’ rest in MLB and the increase in the risk of injury associated with it seem to track each other. It’s not clear which one came first, but it seems that either pitchers are no longer conditioned to be able to throw on three days’ rest or teams have slowly realized that it was a bad idea as they have gotten better at diagnosing what might have previously been “hidden” injuries.

We will not have a four-man rotation any time soon, but what if we had a four-and-a-half-man rotation? In this model, teams assemble five starters, but the fifth guy pitches only when his team plays five games in a row. If there’s an off-day, he gets bumped. In 2017, 49 percent of starts were made on four days of rest and 40 percent were made on five or six days of rest. Again, research that I have done shows that pitchers perform neither better nor worse than their overall stats suggest they would when they pitch on four days of rest or five. So, if you have a pitcher who is fully rested, and he doesn’t gain anything from having an extra day of rest, why give the ball to someone who is, by definition, worse than him?

Teams don’t have to be dogmatic about it, but skipping the fifth starter once in a while could give an extra start or two to each of the other four in the rotation. During weeks where he is not needed, the fifth starter could be used in relief or he can be shuttled off to the minors so that his team can instead have an extra specialist reliever or a bench bat. It’s the sort of strategy that can prevent a few extra runs per year, not based on who’s on the team, but on how we use those players.

Here’s another, more radical, idea to chew on. What if there weren’t any starting pitchers? Yes, someone would be on the mound as the game started, and he would technically be “the starter,” but what if he had a very different job description than we were used to. A starting pitcher is expected to begin the game and to pitch the majority of the team’s innings for that day. In 2017, the starting pitcher averaged less than 5²⁄₃ innings. That’s quite low by historical standards (in 1917, the average starter went more than seven innings per outing), but it still accounts for almost two-thirds of the game. The MLB rulebook even requires that for a starter to be awarded a win, he must pitch at least five innings. If he doesn’t, the “winning pitcher” is at the discretion of the official scorer. It’s supposed to be given to the most effective reliever for the day, but it may not be given to the starter, even if he pitched 4²⁄₃ perfect innings.

In 1993, then–Oakland A’s manager Tony La Russa (hello again!) tried an experiment in real time with an A’s team that eventually lost 94 games. Instead of tasking one pitcher with throwing 100 pitches and six or seven innings (something that his staff struggled mightily with that year), he instead created three groups of three pitchers and asked them each to throw 40–60 pitches and hopefully three innings. The starting groups would take their turn every third day. La Russa reasoned that if his pitchers were having trouble making it through the mid-section of the game, why ask them to do something that they weren’t good at. On Monday, July 19, 1993, Todd Van Poppel threw four innings and 49 pitches to the Cleveland Indians and was relieved by career-starter Ron Darling, who also threw four frames. The A’s lost. Undaunted, on Tuesday night, La Russa “started” Mike Mohler, who struggled through an inning and two-thirds. Eventually, Bobby Witt, making only his second career appearance in relief, pitched four reasonable innings. The A’s lost that one too. It’s probably most telling that by the following Monday, the A’s started Darling and he threw 94 pitches and went six innings against the Angels. The experiment was over a week after it began.

During the La Russa rotation experiment, the A’s went 1–5, but even despite their poor showing, maybe La Russa was on to something. What if part of the reason why it’s so hard to find five good starters is because there aren’t 150 pitchers who have the tools to consistently make it through six innings? What if, instead of a mad search for those who can, teams upcycled the parts that they already had on hand?

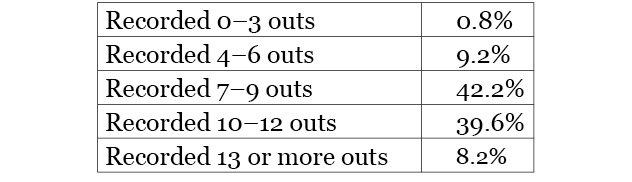

If there’s one nice thing to be said for the 5-6-7 model of starting, it’s that it has the ability to provide a lot of innings from only five roster spots, but if we’re to scrap the 5-6-7 model, we need some idea of what we need to replace. Let’s look at how deep into games starters actually went in 2017.

Table 10. Number of Outs Recorded by Starters, 2017

We’ll need to replace an average of just under six innings each night. Let’s say that instead of asking one pitcher to throw 100 pitches, we ask two pitchers to throw 50 each. How many outs can a pitcher tally in 50 pitches?

Table 11. Number of Outs Recorded by Starters by Their 50th Pitch, 2017

The average starter recorded just shy of 18 outs in 2017. By his 50th pitch, the average starter recorded 9.4 outs. Even if the starters changed nothing about themselves, we can feel confident that two starters throwing 50 pitches would likely record 18 or 19 outs, on average. Those are averages, so night-to-night the number would vary, but at least we know it would balance out in the long-term. If all went well, we could probably replace the bulk innings that the 5-6-7 model provides.

We’re going to run in to a couple problems though. For one, the best-case scenario here is that our pitchers would throw 50 pitches and then have two days of rest. We’d need three sets of two pitchers, for a total of six “starters.” That means that we’ve spent an extra roster spot and gained nothing in terms of innings covered. There’s also a problem of variance. Starting pitchers have better stuff in some outings than in others. Some are more consistent, but in the 5-6-7 system, we accept that on some nights, the starter is going to flame out after pitching 2¹⁄₃ horrible innings. There will also be a night a month later where that same starter will pitch eight strong innings.

With paired starters, one guy might be having a really good day and get you four innings in his allotted 50 pitches. The problem is that his tandem buddy is most likely to be having an average day and he’ll get you 9½ outs, or three innings. On the flip side, it’s possible that the first guy will flame out and only get through one inning, but his tandem buddy will come in and again, he is most likely to be having an average day and will get you 9½ outs. The tandem model limits the risk of the type of outing where the starter(s) don’t get out of the third inning, but it also limits the chances of the starter(s) stretching into the eighth. It’s not that either can’t happen, it’s just going to be rarer. The tandem system is lower risk, but it’s also lower reward.

Here we run in to a quirk of how the rules governing an MLB roster inadvertently shape that roster. The 5-6-7 model compensates for this risk nicely. If the starter goes eight innings, that’s wonderful. If he flames out early though, teams usually have a designated long reliever. He’s usually an expendable “arm” who’s trying to prove that he’s not expendable, and if the starter has flamed out, it usually means that the score is 14–2 and the game is effectively over, barring a minor miracle—and when has one of those ever happened? It doesn’t really matter who the long reliever is or what he does as long as he gets the team through the sixth with his arm still attached. If he has to pitch four innings, his team has the option of sending him back to Triple-A and some other fresh expendable arm can be called up to take his place the next night. Because teams can get another long reliever on short notice, they can afford to use a starting pitching strategy that is higher risk in terms of filling innings. It’s remarkable to think that one of the reasons that the five-man rotation exists is because it’s so easy to find and replace bad pitchers.

There are other ways to do the tandem model. Obviously, if a team has a Cy Young contender already in its rotation, they wouldn’t want to restrict that guy to 50-pitch outings. If a team had two “real” starters (1, 2) and then two tandem pairs (3/4 and 5/6), the starters could rotate 1, 3/4, 2, 5/6, 3/4, 1, 5/6, 2, 3/4, 5/6, but again, we sacrifice a roster spot.

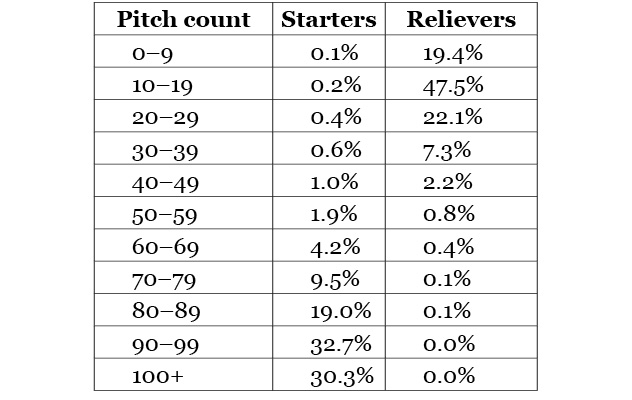

Then there’s a practical problem: spare parts. Pitchers tend to get injured a lot. The way that rosters are currently constructed, there are two main roles on a pitching staff. The starter throws 100 pitches. The reliever throws 20. Our tandem starters would theoretically be throwing 50, even though the idea of a 50-pitch outing doesn’t currently exist in MLB.

Table 12. Percentage of Outings within Pitch Count Ranges, 2017

We see that it’s rare that anyone, starter or reliever, has an outing in the 40–70 pitch range. If a team loses a starter to injury, they can easily find someone in their minor league system or in the discard bin who is at least trained to throw 100 pitches (even if those pitches aren’t all that great). If one of the tandem starters broke, how would a team replace him? There’s almost no one in the league trained to do that, meaning that a team would need to find nine or 10 of these 50-pitch guys and have them in-house just to make the system work. They’d also need spare parts for their bullpen and for their “regular” starters.

It turns out that the five-man rotation, much like democracy, is the worst system in the world, except for all the other ones that we might try. The four-man rotation might have its advantages, but we’ve reached a point of no return on that one. Systems involving tandem starters require exactly the right roster, and rely on types of pitchers who may not exist in enough abundance for even one team to make it work. So, despite the freedom that we have to choose any type of crazy starting rotation that we want, we find that the boring 5-6-7 model seems the best suited to the realities of baseball, because it provides bulk innings with a minimal commitment of roster spots.

Before we leave the tandem starters though, perhaps we have learned something useful that we can take with us into the bullpen. There is another word that is lacking in our baseball vocabulary. This time, it’s a word for a pitcher whose job is to throw 50 pitches. He’s not a starter, nor does he fit into the usual mold of a reliever. Indeed, if a team tried to sign a player to fill such a role, what should they tell him his job is? But in that lack of a word is the presence of an opportunity. There once was the word “fireman,” although that had a specific meaning of a pitcher who could be counted on specifically in high-leverage situations. What would we call someone who was capable of throwing three innings, but who didn’t need to be the best reliever in the bullpen? What if he were simply average?

Right now, there are probably pitchers who would excel in a three-inning role. The thing is that because there are so few pitchers who can pitch six good innings on a consistent basis, if a pitcher shows the ability to go three solid frames, he is likely to keep being pushed out there for the fourth and fifth inning, in the vain hope that he will become a “good” starter. When he doesn’t, he will bear the label (and perhaps the price tag) of a “failed starter.” There might be other guys out there who have already been converted into bullpen roles, but who could be so much more than a one-inning guy. What if there was a half-way point for those guys where they could do what they are actually good at?

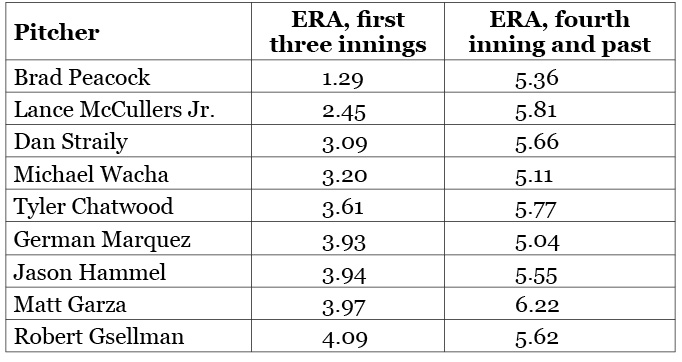

I looked in the data to see if there were guys who fit this mold. In 2017, the average reliever had an ERA of 4.15 and the average starter had an ERA of 4.49. What if we could find a starter who had a better ERA than the average reliever in his first three innings, but was awful from the fourth inning onward, perhaps because he didn’t have the stuff to turn over a lineup more than once? It would mean that—doing nothing differently from what he has already done in the past—he has the ability to go three innings at a time and to pitch like a league average reliever.

Table 13. Starters with First Three Innings ERA under 4.10, but ERA over 5.00 Past That, 2017 (min 100 IP)

These are just the cases that jump out of the MLB data set. There might be other pitchers knocking around in the minors who haven’t made the leap to the majors because they are not “real” starters yet. The problem is that baseball’s language only has two words to describe pitchers (“starters” and “relievers”), and if you don’t fit into one of those two boxes, you are described as a “failure,” and “failed” is a powerful word. Sometimes when there is no word for something, we don’t realize not only that something exists, but that it’s sitting in front of us.

Our reliever wouldn’t even need to be a particularly noteworthy performer. His performance could be average, which means there’s a place for him on a Major League roster. His ability to fill multiple innings from one roster spot with league average results could be very valuable in a bullpen world where everyone else is trained to go one inning. There are certain games during a season which are won because one team had more capacity to throw not-awful relievers for longer. There are certain games where a starter exits in the fourth or fifth inning though the game is still winnable. It’s too early to bring in the late-inning corps, but the traditional long-man is likely a below-average reliever who is a poor choice for a game that calls for someone who knows what he’s doing. If nothing else, his ability to soak up a few innings means that a team might not have to lean so heavily on one of its other relievers who is below average. So, we will be on the lookout for “failed starters.” If we look at them from a different angle, we might see treasure in another man’s trash. All that we needed to do was to reinvent a word to describe them.

* * *

In Chapter 3, we saw that despite the obsession with the ninth inning and the “closer,” the most important innings that a team faces in a year are in games that are close rather than late. A one-run lead in the seventh inning is a more important situation than a three-run lead in the ninth. There’s a message in there for roster construction. A team would do well to make sure that they have three very good relievers, rather than just one. The reason is simple. If the most important situations that a team will face all year can happen in the seventh, eighth, and ninth innings, there will be games in which all three of those situations happen, and a team will need three good relievers (or some combination of good relievers capable of handling three innings) to staff them.

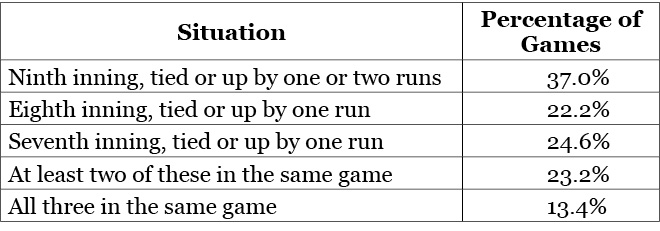

Table 14. Percentage of Games in Which Teams Faced a High-Leverage Inning, 2013–2017

(Note: all cases represent the game state at the beginning of the inning)

In 13.4 percent of games (22 over a 162-game season), the average team is going to face three of these critical-situation innings. That might not seem like much, but these are the specific situations where the game could go either way. Being 12–10 in them versus being 10–12 in them could make a huge difference at the end of the season in making the playoffs.

In constructing our bullpen, we will prioritize our top three relievers over the rest of the crew. If a closer is worth obsessing over, the seventh- and eighth-inning guys, who are sometimes afterthoughts on a roster, are just as important. We will treat them as such in allocating our scarce resources. In our seven-man unit, we will have three ace relievers who will be tasked with pitching in high-leverage situations in the seventh, eighth, and ninth innings (and will cover a few other innings here and there as the need arises). We will hopefully have our three-inning specialist that we have reclaimed from the scrap heap, and we will have three other pitchers who will sop up garbage time innings. “Garbage time,” oddly enough, includes three-run, ninth-inning save situations.

* * *

Now that we have some idea of what roles our pitchers will fill, what sort of pitchers should we chase? The answer to that question might depend somewhat on who will be standing behind him. Among pitchers, we know there are grounder guys and fly-ball guys. What if we put a ground-ball pitcher in front of a really good infield? We have discussed that he would likely get better results than if he was standing in front of four lead-footed lads. How much value can we expect?

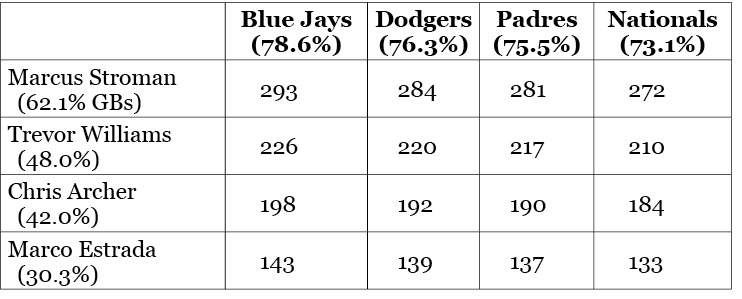

In 2017, the best fielding team on ground balls was the Toronto Blue Jays, with 78.6 percent of grounders turned into outs. The worst was the Washington Nationals checking in at 73.1 percent. In 10th place (a third of the way down the list), we see the Los Angeles Dodgers, and in 20th place, the San Diego Padres. This gives us some realistic boundaries of what a “good” and a “bad” infield defense might look like. In 2017, among pitchers who threw at least 150 innings, the highest ground-ball rate belonged to Marcus Stroman, with 62.1 percent of his balls rolling along the grass. The lowest belonged to Marco Estrada, with a 30.3 percent rate. Our one-third of the way down guy was Trevor Williams and two-thirds of the way down, we find Chris Archer. This again is meant to give us some idea of what the bounds of a high, medium, and low ground-ball rate are.

Now, let’s make a nice grid. Let’s assume that our starter gives up 600 balls in play (about average) during a season. We can estimate how many ground-ball outs a pitcher would record standing in front of each of the four defenses.

Table 15. Expected Ground-Ball Outs, 2017 Data

We can see that for the same pitcher, standing in front of a good defense means more of their balls in play will turn into outs. To take the extreme ground baller (Stroman) as an example, we expect him to generate about 373 ground balls over 600 balls in play. Moving him from the best ground-ball defense (the Blue Jays, in this example) in the league to one that is merely above average (the Dodgers), would cost him about nine extra balls that weren’t turned into outs, and instead, go as “hits allowed” on his record. Again, that might not sound like much, but the value of turning a ground ball from a single into an out is roughly three-quarters of a run, which will make Stroman’s results more than half of a win worse, just based on the four men standing behind him, even if he does nothing differently. Baseball’s lexicon again lacks a word for this sort of intersectional effect.

A team doesn’t even need to go to the extreme cases to generate a good amount of value. We project that when Trevor Williams, who has a medium-high ground-ball rate, is placed in front of an elite infield, his team gains about five extra groundouts compared to the merely good infield. Chris Archer, with the medium-low ground-ball rate, would gain an extra four outs. Williams himself might only be worth one extra ground-ball out compared to Archer, but if a team can get one extra ground-ball out from each of its pitchers over the course of a season by being cognizant of how all its pieces fit together and signing more Williamses than Archers, then they may be able to prevent a few extra runs. If you have good infielders, sign pitchers who will feed them more ground balls.

* * *

Now that we’ve designed some structural principles for a pitching staff, we need to think about the other half of the roster. With eight fielding positions and, depending on the league, a designated hitter to find, and only 12 or 13 roster spots to use, we’re going to need to be economical. Most teams follow the model that they have a designated regular starter at each of the positions, with the remaining spots going to lesser players who will fill in now and then.

Since we are starting from nothing, we may stop to ask whether we should prioritize a certain position over others. Perhaps teams should focus on signing a center fielder over a third baseman? The answer to this one isn’t quite as interesting as one might hope. A lot will depend on which players are available at which position.

For instance, imagine a league where there are 30 center fielders. One of them is amazing and the other 29 are dreadful. That one All-Star is going to have a lot of suitors, because you’re not just paying for his services, but you’re also paying for the fact that you get to avoid all of the other bad options. The problem is that the other GMs in the league are going to notice his talent as well, and will bid up his price accordingly. If you end up with the amazing center fielder on your roster, it’ll probably be because you were willing to pay a lot of money.

In economics, this is known as the Winner’s Curse. You “win” an auction because you were the person willing to spend the most money. If you are at an auction with a bunch of fools who don’t know what they’re bidding on, there’s room for being the person who is willing to spend the most. Unfortunately, there are no fools in front offices. About the best you can hope for is to find little bits of value that other people don’t realize are there and the market is underpricing.

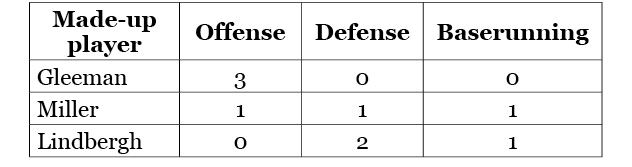

The more interesting question is whether a team should build its position player suite around power or speed or defense or maybe a little from each column. Suppose we had three players, all of whom we rate as “three-win” types, but who draw their value from very different areas.

Table 16. Completely Made-Up Players

Lindbergh is obviously the best defender, but will probably need to hit eighth. Gleeman has a bat that he uses to hit long home runs and field ground balls. Miller has a more well-rounded game without much of a weakness. So, who’s it going to be? Recall that one of the strengths (and weaknesses) of Wins Above Replacement (WAR) is that it evaluates a player by stripping out the context of who a player plays with. WAR would see all three of these players as equals, but now that we are creating the-perfect-team, we want to know how each player’s talents might interact with those of the rest of his teammates. We need more than just WAR to make this decision.

If we take Lindbergh for his defense and can hit him eighth or ninth, then we can bury his bat, but the more all-glove guys we have, the higher in the order he will have to hit. If we take Gleeman, we can hit him near the top of the lineup, but we’ll have to live with the defense. Which is more valuable?

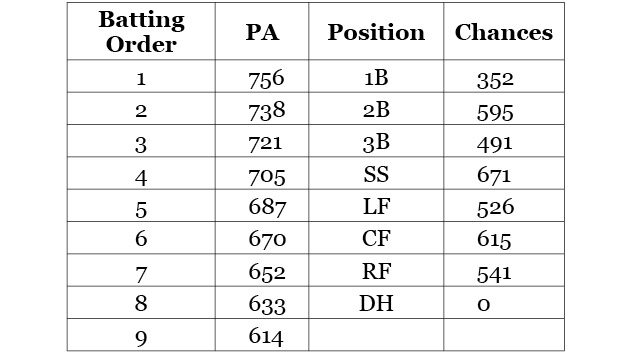

Let’s start with some numbers from 2017. The first set is how many times each spot in the batting order came up to bat over the course of the season (average for each team) and the second is how many chances each fielding position had to make a play on defense. (Catchers were excluded because their primary defensive duties are much different than those of the other fielders.)

Table 17. Plate Appearances by Batting Order Position and Chances by Position, 2017

The defensive numbers line up with the conventional wisdom that it’s best to have better defenders up the middle, because they handle the most chances. There are only so many corners in which to hide a bad glove. We also see that for each spot that a player gets pushed up (or down) in the lineup, he will gain (or lose) between 15 and 20 PA over the course of a year.

To go back to our three create-a-players above, suppose that we are considering replacing Miller, the all-around balanced player, with Lindbergh, the more talented defender. Lindbergh’s defense is an upgrade over Miller’s, though Lindbergh’s hitting is, in a vacuum, an equal amount worse than Miller’s. Miller hits sixth in the lineup currently, but Lindbergh will have to hit eighth and the current seventh and eighth hitters would have to bump up a notch. Trading Miller for Lindbergh therefore makes three spots in the lineup a little bit weaker, but perhaps the defensive upgrade that Lindbergh provides can make things worth it.

There’s a fundamental difference between how these teammate-interaction effects work on offense and on defense. The ability of a lineup to produce runs essentially relies on emergence. The only way that a batter can produce a run all by himself is to hit a home run. In 2017, there were 22,582 runs scored and 6,105 home runs hit, meaning that 73 percent of runs scored in 2017 involved one batter getting on base followed by another batter somehow knocking him in. We also know that batters do not come up in random order. If we have a leadoff hitter who is good at getting on base, the hitters who will have the most say as to whether or not he scores are the second and third hitters in the lineup. For a lineup to succeed in its mission, it needs good hitters who are bunched together so that they can get their hits in sequence. In addition, when a batter either walks or gets a hit, he not only adds value to his team, but he doesn’t make an out, and that means another plate appearance for someone else. The more good hitters a team has, the more valuable those extra plate appearances are.

Conversely, if a team has several bad hitters, they will make outs more often and that will deprive the better hitters of a few extra turns at bat. Offense in baseball is structured so that a team with a critical mass of good offensive players will see compounding benefits. A team with a critical mass of bad hitters will see a similar compounding effect, but in a negative direction.

On defense, the story is different. In theory, having a good-fielding second baseman and a good-fielding shortstop should provide good value for the team. At the very least, we assume that the two of them won’t get in each other’s way, but that’s not what happens. I’ve done research where I’ve found that a shortstop playing next to a good-fielding second baseman is less likely than we would expect to make a play on a ball than when he’s playing next to a bad defender, even controlling for how hard of a play he had to make. (The effect also shows up for a second baseman playing next to a good shortstop.)

In psychology, there is a concept called the “diffusion of responsibility” that applies here. In an emergency situation, people are quicker to respond when they are the only person in the room. They hesitate when around others, because someone else might call for help. The shortstop, seeing a ground ball headed up the middle, but knowing that his keystone partner has some range, might hesitate just enough to let a ball or two go through now and then. When playing next to a lead-footed fielder, he might feel that everything depends on him and react a bit faster. Installing a good-fielding second baseman doesn’t end up as a net negative, but the effect on the shortstop takes away a little bit of the value that the team thought it was getting. On defense, having a critical mass of good fielders actually diminishes the value that each provides. The effect sizes are not large, but they are not zero either.

In an ideal world, we would find a player who is good on both offense and defense, but again, “find someone who is good at everything” is not a strategy. It’s a goal. Given the choice between two otherwise equal players, one of whom specializes in offense and the other in defense, we will have a preference for the better batter.

* * *

There’s one other cheat code that we haven’t talked about yet. There are players in baseball who have the ability to competently play more than one position on the diamond. They hit well enough to be regulars, but don’t mind shifting around in the field to fill whatever gap is needed. With apologies to 1980s and 1990s super-utility player Tony Phillips, the modern patron saint of these multi-instrumentalists is Ben Zobrist, who came into the league with the Tampa Bay (Devil) Rays in 2006 as a shortstop, but quickly found a home in not having a home on the diamond. He was a good hitter and had the athleticism to play some tough defensive positions reasonably well. The nice thing about his versatility was that by being willing to pack several different gloves in his suitcase, he allowed other value to emerge.

There are a few things that a Zobrist allows a team to do. He can allow a team to build a mixed-position platoon. He can allow his team to shift guys around in the late innings and replace a poor-fielding player in one position with an all-glove no-hit player at another (with our super-utility guy bridging the gap). He can enable a team to be much more efficient when it comes to giving players days off. The Zobrist Effect turns out to be meaningful.

Platoons are a well-known strategy for making one good player out of two flawed ones. In 2017, right-handed batters overall had an on-base percentage of .314 against right-handed pitchers, but .332 (18 points more) against lefties. Flipping that around, lefties had better outcomes (.336 vs. .310) when they faced a right-handed hurler than a left-handed one. Some individual hitters have more extreme splits than that, but if a team can find two guys who are both good hitters against one sort of pitcher and they both play the same position, they’ve got themselves a platoon. What happens if you have a right fielder who feasts on righties and a second baseman who loves hitting against lefties? If you have a Zobrist who can bridge that gap, you have a mixed-position platoon!

Having a Zobrist on the roster means that a team can expand the universe of platoon-eligible players that it can draw from, making it easier to construct platoons and construct better ones. If we assume that the platoon effect is worth about 20 points of on-base percentage and that our Zobrist allows his team to gain a platoon advantage that they otherwise wouldn’t have gotten in an extra 100 plate appearances per year, that’s two additional on-base events that they can grab. Remember that turning an out into a single is worth roughly three-quarters of a run. That’s an extra run and a half of value that our Zobrist’s versatility adds to the team’s ledger, just by having an extra glove in his locker.

Teams can similarly use their Zobrist to facilitate a cross-positional defensive replacement. Assuming that our Zobrist plays average defense anywhere on the field, it means that late in the game, a team might be able to pull a poor defender from one position, say a bat-first second baseman, slide their Zobrist into that spot, and put their glove-first center fielder into the game in the eighth and ninth inning. A poor defender will cost his team about 20 runs in the field compared to an average fielder over the course of a season. A very good defender will save his team about 20 runs. What if a team could effectively replace a bad defender with a good one for 100 innings out of a season? That change would be worth about two and a half runs. Again, that’s not going to turn a bad team into a pennant winner, but it’s free value that can be had and is easier to grab if you have someone who can bridge those gaps.

Finally, a Zobrist allows a team to be more efficient when it gives days off to players or when it deals with injuries. If your second baseman gets hurt and will be out for two weeks, someone from the bench must take his place. The problem is that your team carries only one player on the bench who even has a clue at second base, and he is the worst hitter of the bench mob. Oh, if only your fourth outfielder could play second. He’s not a great hitter, but he sure is better than the utility infielder. What if we could shift our Zobrist back to second and have the fourth outfielder take over in right?

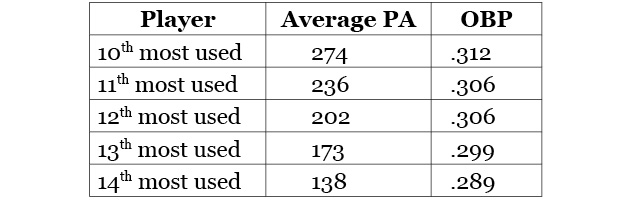

Hitters who ride the pine do so for a reason. Either no one has yet recognized their brilliance, or there isn’t any brilliance there to recognize. There are still differences between the best guy on the bench and the worst. Using data from 2013 to 2017, we can look at how often a team’s 10th most used hitter (by plate appearances) came to bat and the average OBP that he provided. We can do the same for the 11th most used hitter and the 12th and on down to the end of the bench.

Table 18. Bench Production, 2013–2017

Being able to use the first guy on the bench to replace a guy who is hurt is worth 23 points of OBP over the last guy on the bench. Yet how often does the light-hitting utility infielder play because he’s the only one who can fill in at shortstop? What if we could shift some of those plate appearances from number 13 and number 14 to number 10 and number 11 on that list? A Zobrist might be able to make that happen. If we were able to divert even 100 PA away from those bottom-of-the-bench players to our top hitter, it could be worth a couple of extra runs to his team. Every little bit helps.

One Zobrist is not going to be able to facilitate all of these tricks, but he might enable one or two. The more flexible the Zobrist (and the more Zobrists on a team), the more opportunities to realize some of this extra value around the edges. It’s value that a Zobrist adds, not because of what he does with a bat or a glove, but because he’s willing to change his glove. It’s value that should be recognized.

* * *

Let’s come back to reality. Real Major League teams are never actually in this sort of “original position” (and yes, philosophy majors, this is a shameless baseball adaptation of philosopher John Rawls’s work), where they are constructing a team from the ground up. They have to work within the constraints of what their farm system has produced and what free agents are available when they are out shopping. No one is going to build a team exactly like this, but they might be able to use some of these principles.

Talent is still going to be the primary driving factor in how well a team does, but there’s a place for understanding emergent value as well. Baseball teams and fans alike have spent the last century and a half trying to figure out and measure “talent” in baseball. There aren’t many hidden needles in haystacks when everyone has a metal detector. On the other hand, there’s a painful lack of a statistic or even a word that describes the value that teams gather from these emergent sources, in which players provide value by the ways that they fit together. It’s hard to think about things that don’t have a word to describe them. How does one search for something that doesn’t have a name?

So, if you’re an enterprising researcher who wants to discover something new in baseball, this is a good place to start. Think like an engineer—a baseball engineer. It’s a lot more fun than just reciting a list of All-Stars.