2

Surface Play

Flash, Friction, and Self-Reflection

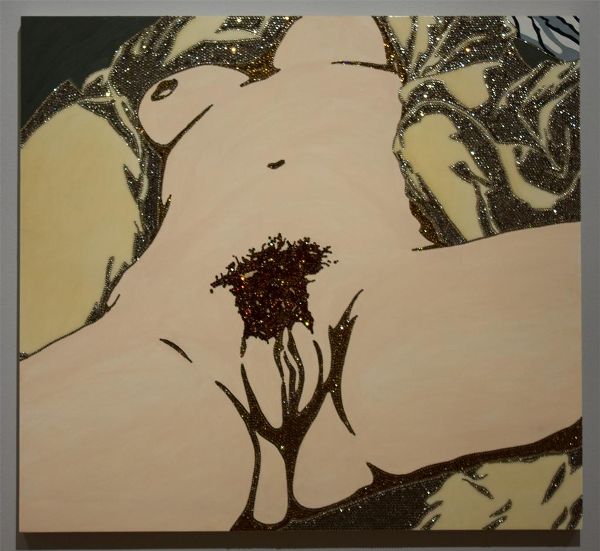

In her painting of a rhinestone-encrusted black vulva, Mickalene Thomas challenges our understanding of black women’s relationship to knowledge and self-production. She explores and rejects the conventional objectifying discourses of scientia sexualis—an expansive set of logics that includes the exploitation of black women’s bodies within gynecological experimentation and a pornographic gaze that seeks to fix the truth of race or gender within black women’s splayed legs. Instead of trafficking in this legacy of anonymous pain, Thomas illuminates the pleasures of tactility and opacity offered by excess surface.

Most overtly, Thomas’s Origin of the Universe 1 (2012) revises Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World (1866), a painting that created a minor scandal when it was unveiled because it dared to bring the pornographic into the milieu of fine art.1 In contrast to other nudes of the era, Courbet’s elision of the rest of the naked figure directed viewers’ gazes to that which had circulated mainly in private spaces—the vulva. We can also read his decision to absent the model’s head, legs, and arms as emblematic of a sexological discourse that sutures female sexuality to the genital, while his deployment of a realist aesthetic allows us to see how this painting furthered pornography’s argument that sexuality is visually knowable. As such, The Origin of the World was imagined to transmit truths not only about genitalia, but also about sexuality as a whole. That the painting purported to illuminate “the origin of the world” further amplified this aura of truthfulness. This knowledge was, however, understood to be private, since Courbet assumed that whoever possessed the painting would want to conceal it because of its provocative nature—indeed, Jacques Lacan, who owned the painting for many years, kept it hidden behind a screen in his house in Guitrancourt.2 However, as Linda Williams reminds us, the practices of visibility and categorization that underlie pornography and sexology also reify the notion of invisible female pleasure and enigmatic female sexuality: “This maximum visibility proves elusive in the parallel confession of female sexual pleasure.”3

Figure 2.1. Mickalene Thomas, Origin of the Universe 1, 2012. Image and original data provided by Larry Qualls; Photographer: Larry Qualls; © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

While Thomas takes her cue from The Origin of the World, she draws on this representational conundrum to present queer pleasures, making a spectacle of their unknowability by bringing our attention to the surface and the importance of opacity. We can understand Thomas’s reworking of Courbet as part of a larger project to portray black and brown women as more than merely objectified. In her framing of Thomas’s work, art critic Roberta Smith writes that her “quotations are notable for going beyond mere one-liner mimicry or conceptual appropriation; they radically de-Europeanize and contemporize their sources.”4 The de-Europeanization that Smith refers to is not just a matter of Thomas’s drawing on black and brown models, but of her doing so in a way that moves them away from the space of pornographic objectification and positions them as selves with their own erotic pleasures. It is notable, for example, that in contrast to Courbet’s anonymous model, the genitals that Thomas paints are her own. This fact positions her as both subject and object of her own creation, signaling her agency and her self-awareness of her objectification within an economy of scientia sexualis, and it locates the painting within the realm of brown jouissance.

Thomas produces this portrait of agency, pleasure, and objectification by employing surface as a formal strategy of producing opacity. This activation of a surface aesthetic serves as a rejection of the mandate of transparency, while also enabling alternate modes of apprehending pleasure and selfhood. There are several layers to thinking Thomas’s relation to surface. First, there is the question of size. Origin of the Universe 1 is a large painting (sixty by forty-eight inches), which invites the contemplation of surface as a spectacle. In this way, I understand spectacle to be operating in opposition to the pornographic or scientific gaze in that through its excess, it disrupts the possibility of contained knowledge. Additionally, the nature of spectacle invites us into the specific realm of black hypervisuality through Thomas’s use of the rhinestone and the reflective dimensions of their shine. Instead of vagina as void, the rhinestones emphasize the ways that this vulva’s materiality lies at the center of two epistemologies of intimacy—friction and narcissism.

Rhinestones, Surface, and the Pleasures of Commodification

Origin of the Universe 1 insistently traffics in a spectacle of excess surface and surface excess. In grappling with excess surface, I have already mentioned its large size, but when we think with the rhinestone, we can also see how this form of excess relates to tactility and cover. Surface excess, meanwhile, can be understood to lie in the rhinestone’s relationship to shine and decorativeness. Both concepts help us refine what is at stake in thinking with the surface.

Anne Anlin Cheng argues that the fascination with the idea of the surface emerged from a twentieth-century fetishization of transparency and “the mysteries of the visible.”5 In other words, surface functions as the underside of a scientific and pornographic drive toward locating knowledge in an “objective” image. However, in contradistinction to this ideology of objectivity and transparency, flirting with the surface can, Cheng asserts, lead to “profound engagements with and reimaginings of the relationship between interiority and exteriority, between essence and covering.”6 This means that surface offers the possibility of doubleness, troubling transparency and the idea of authenticity. In this way, surface complicates categorization because it confounds ideas of what knowledge is, where it lies, and how we can apprehend it. Cheng writes that the problem of the modern surface is “distinguishing decoration as surplus from what is ‘proper’ to the thing.”7 In Origin of the Universe 1, what we want to ask, then, is whether surface is about nakedness and being stripped down or about shine and glamor. Reading with surface emphasizes multiple strategies for producing opacity.

In Origin of the Universe 1 Thomas places rhinestones where we might expect to see shadows. They appear in the creases of sheets, to mark the contours of flesh, to demarcate nipples, pubic hair, and labial folds. They disrupt the flat planes of color with their raised and sparkling presence. Instead of peeking inward, we are distracted by surface and ornamentation. Rhinestones offer Thomas a palette beyond oils; they provide a way to expand the surface of her paintings and to gesture toward epistemologies not captured by realism. Meghan Dailey describes the impact that working with rhinestones has had on Thomas’s work:

The rhinestones, some are Swarovski crystal, are what define her paintings. She sets them like jewels in already bold floral and animal prints, creating a dazzling optical intensity and adding, through their sparkle, a sense of movement. She also uses them to outline the contours of the women’s bodies and emphasize their most sensual features—lips, eyes—and parts that are usually concealed: nipples, the lines on the soles of their bare feet. “Oil painting was never satisfying to me,” Thomas explains. “I always felt like I had to put something on it or it was never finished.”8

We might also, however, understand this decorative excess as providing a type of cover, which preserves the opacity of interiority. In this way, Thomas halts the gaze at the surface. In lieu of satisfying the scientific/pornographic gaze’s desire for visual knowledge as “truth,” Thomas presents an excess of ornamentation and cover. Here, we see that in refusing the edicts of interiority, hewing to the surface becomes a radical act in its privileging of opacity. In this, we can read the rhinestone in relation to Krista Thompson’s analysis of the ways that black diasporic artists have deployed shine as distraction in order to produce an “un-visibility,” so that blackness is spectacular, but not knowable.9

We can also read Thomas’s replacement of flesh with rhinestones as a comment on the history of the commodification of brown bodies. This follows from Thompson’s analysis that shine signals “a distinct aesthetic of material excess . . . a ‘bling-bling’ aesthetic—‘bling’ being a word that in its doubling highlights the spectacular display of material surplus.”10 This attachment to materiality acts as a reminder of the long association between black people and the commodity, while at the same time offering an opportunity to take on this objectification as a mode of producing opacity and as emphasizing what happens when we think with the commodity. In other words, shine makes it difficult to separate the fleshiness of black bodies from the materiality of the decorative. This calls into question the separateness of the categories of person and thing without embracing any of the negative affects of commodification. Shine plays joyfully with the idea of the body as body while rejecting the demand to present anything other than surface. Thompson writes, “In many respects, we might see the fascination with adorning and picturing the body’s surface in jewels, the taking-on of the shame of things, as a type of screen.”11 Thomas’s use of rhinestones, then, is also about the inability to separate the flesh of the body from the manmade commodity of the rhinestone.12

We might ask, then, what it means that rhinestones are not precious gems, but relatively inexpensive and disposable. This quality of rhinestones is part and parcel of their resonance with funk, the musical/dance genre that emerged in the mid-1960s from blues, soul, and jazz and gained widespread cultural visibility in the 1970s with acts such as George Clinton, Sly and the Family Stone, and Betty Davis. These musicians melded together rhythmic beats, sexually suggestive vocals, and movement into big, loud performances. Funk is excess surface, something that LaMonda Horton-Stallings argues offers a black radical “rejection of the Western will to truth, or the quest to produce a truth about sexuality, and underscores such truth as a con and joke. In lieu of singular truths about eroticism or sexuality, [these artists] offer multiple fictions of sex to slip the yoke of sexual terrorism, violence, and colonization.”13 The “funky erotixxx” that Horton-Stallings seeks to cultivate “is unknowable and immeasurable, with transgenerational, affective, and psychic modalities that problematize the erotic and what it means to be human.”14 Indeed, from this perspective we can see Thomas’s use of rhinestones as a rejection of the will to truth and an embrace of the possibility of pleasure in all of surface’s excesses.

Thomas’s use of rhinestones also speaks to one of the undersides of reading with surface—the production of part objects. This happens when the surface is mistaken for the whole. Cheng argues that this occurs especially in the fetishization of surface in relation to ideas of race as a surface phenomenon of difference. Seeing racial difference as surface can prevent one from registering the wholeness of those deemed racially Other. She traces this through the fantasy of “remaking one’s self in the skin of the other,” which works both for imagining whiteness as a form of escape and for thinking about brownness as a space of the exotic.15 This fantasy of the surface cannot even begin to imagine interiority because it is so taken with fragmentation. Along these lines, she writes, “The crystallization of ‘surface’ as an aesthetic ideal at the birth of the twentieth century holds profound philosophic and material connections to (not just disavowals of) the violent and dysphoric history of racialized, ruptured skin.”16 This is to say that the maintenance of the integrity of one surface may be dependent on the breaking up of another. In addition to rendering her pleasures opaque through distraction and cover, then, Thomas’s use of rhinestones can also be read within the framework of fragmentation. By bedazzling the painting of her vulva, Thomas produces herself as a set of part objects, so that the final product is whole, but the fragments remain. On the one hand, this breaking apart prevents us from imagining that we are seeing all of Thomas; on the contrary, it highlights her opacity, even as she has made a portrait of her vulva available to us. On the other hand, in her existence as part object—especially vulval part object—we see the possibility of the objectifying gaze that registers her as consumable.

While I use the rhinestone and its aesthetics of surface excess as an example of brown jouissance’s strategic fleshiness, in this inability to exist untethered from racist and sexist imaginaries we see the perils of strategies of the flesh. This oscillation between opacity and vulnerability is one of the difficulties of trying to sever surface from depth, and it invites us to think about this manifestation of brown jouissance as excess surface in relation to tactility. Since the duality of self-making and objectification become encoded on the surface of the painting through the rhinestone, touch is another way to think about the work that brown jouissance accomplishes. This zone, where the depth of interiority becomes perceptible on the surface, is what Rizvana Bradley names the haptic. She writes, “The haptic can be understood as the viscera that ruptures [sic] the apparent surface of any work, or the material surplus that remains the condition of possibility for performance.”17 Further, this physically tangible surface excess allows us to see touch as a form of penetration. In this, I follow Kathryn Bond Stockton, who in her critique of surface reading—a movement within literary studies that favors the descriptive—argues that words penetrate their readers in order to gain meaning.18 Stockton compares reading to kissing: “Think of all that happens when you kiss a text (if I can use these terms). Penetration’s in the kiss. A dizzy array: kissing with your eyes (since you don’t lick a text) becomes in an instant a penetration of you; from this penetration, there’s immediate birth.”19 Kissing’s tactility is put on display as a mode of coming toward an understanding of interiority. In this analogy, Stockton argues that it is impossible for something to remain “only” on the surface. The act of perception (in this case reading) is objectifying. In another essay on the same topic, kissing becomes barebacking, which Stockton codes as “lesbian”: “Gay male barebacking is like dildoing is like kissing is like reading: it’s a fetishizing of a sign and surface that must get inside us, where a sign-and-surface birth and cause some death.”20 In a cheeky reading of surface, Stockton arrives at the lesbian by reading an attachment to surface as its own form of penetration because of the impossibility of grappling with surface without coming toward penetration. In Stockton’s writing, the word “sign” is what comes to signify surface, but signs cannot be thought without activating individual and cultural understandings of these concepts, which can be described as penetrations of the word. This is better understood when she elaborates on the term “lesbian”:

We have been dildoed by the sign “lesbian.” We’ve been pleasured by it, as it’s come inside us—I’ve had to try to take it like a man—but we’ve also split from each other at the very point of our contact with the sign. Somewhere where denotation births connotation, we start feeling erotic rips and tears. Ours is truly a fractured sameness in several directions. We are like the figure of two lips touching, touching through their gapping, that Luce Irigaray offered and explored in the 1970s as a figure for (self-)caressing through (self-)splitting (lips I wrote about in the 1990s as a figure for a sexual self-estrangement). Through our contact with the sign “lesbian,” my lover and I, so profoundly different, touch upon the nearness Irigaray conceptualized through the touching lips, deriving pleasure “from what is so near that [we] cannot have it, nor have [ourselves].” Some self-fracturing, breaking sameness, is to be found in a “lesbian” kiss.21

This gap between the sign/surface and experience is where Stockton locates attachment, pleasure, and meaning-making. This is also the space between Thomas and the histories of black femininity that she references in Origin of the Universe 1. While Thomas uses her self-portrait as an expansive and ornamented surface, she cannot help but be penetrated by the sign of black woman. In summoning her own agency, she cannot escape her objectification, but she does have tools for augmenting the space between sign and surface—queerness and rhinestones—and, in this production of the gap, black femininity penetrates the viewer differently. I register the painting’s penetrations as moments of brown jouissance in which Thomas’s fleshiness claws back at objectification.

Sister Outsider: Surface Residue and Generational Friction

That Thomas’s rhinestones evoke a 1970s aesthetic is not incidental; they serve as a marker of her attachment to 1970s womanism, which she describes in an interview with Sean Landers as “formed in large part by Audre Lorde’s discussion of a Sister Outsider, of being a part of feminism but still being outside and under recognized.” As Kara Walker does, we might read this attachment as a form of nostalgia: “Thomas’s paintings signal nostalgia for that transitional moment when desire, individuation, and upward mobility press against Blaxploitation.”22 However, Thomas herself pushes against this framing to argue that her attention to the 1970s is part of a “recontextualizing process” designed to show the complexity of who she is: “I try to incorporate all these aspects of myself in my work: what I grew up with, what I’m inspired by—textiles, African photography, Yoruban art, Cubism, Matisse. How can I take the ingredients of who I am and put them into a painting? What does that look like? What does that feel like? What’s the residue of that?”23 Through Thomas’s emphasis on residue, we see what happens when one brings womanism, which I read as a politics that draws attention to the frictions within feminism, to the surface.24

This turn to womanism renders Thomas’s choice to use the word “universe” instead of “world” (as Courbet did) significant. It indicates an epistemology in which queer black sexuality is the point of origin. In some ways this is literal. Though she passed away in 2012, Sandra Bush, Thomas’s mother, was not only a mother, but also a muse:

As an artist I have always been astonished not only by my mother’s strength and tenacity but also by her sustained elegance and charisma in spite of harsh obstacles. Although she was not able to attain the adulation she desired from the fashion industry, her flair as a model and entertainer was perpetually self-evident. Sandra became the model for my own photographic investigations. We worked together in a productive artist-and-muse relationship, ultimately generating a series of photographs and paintings known as “Mama Bush.”25

Their collaboration also helped to heal a rift caused by Bush’s drug use while Thomas was a teenager. In an interview with the New York Times, Thomas frames these sessions as “a kind of therapy. I began to look at her as a person and accept her weaknesses, her failures.”26 Thomas portrays her mother in numerous guises: “Mama Bush, as her mother is known, has stood in for everything from a 1970s diva to a nude odalisque in some of Thomas’s exuberant, rhinestone-encrusted collage-paintings; in the 2009 video piece ‘Ain’t I a Woman (Sandra),’ Bush vamps to Eartha Kitt in a bold red-and-black sweater with big shoulder pads.”27 But, through an elastic reading of generationality, I prefer to think about the ways that her mother also stands in for her. We see this most poignantly when Sean Landers asks her whom she sees in the mirror and Thomas answers, “It’s always me. Sometimes it’s also my mother, my grandmother, or my great-grandmother.”28 In this imagination of an expansive matrilineal selfhood, Thomas echoes words from the prologue of Lorde’s biomythography, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name: “I have felt the age-old triangle of mother father child, with the ‘I’ at its eternal core, elongate and flatten out into the elegantly strong triad of grandmother mother daughter, with the ‘I’ moving back and forth flowing in either or both directions as needed.”29 I read this as a way to think queer black sexuality through the expansive self that is created by thinking with the maternal. In this, I argue not only for a consideration of Thomas as mother or child, but for a more capacious understanding of the maternal as a form of multigenerational selfhood.

Thomas’s insistence on having this expansive self and its sensuality, desire, and woman-loving politics meet as “residue” reminds us of surface’s connection to touch and the fleshiness of the surface. The residue that Thomas invokes does not remain in the past, however; it frames our current perception of the black female body. By insisting on a language of maternity and sex, she brings the residue of Lorde and womanism into the future. This is the origin of a new universe, attentive to the radical insights of Lorde’s feminism while open to the surface possibilities of friction. In this resignification of the past, I see Thomas’s emphasis on residue operating as a sign of temporal drag, to use Elizabeth Freeman’s term. According to Freeman, temporal drag looks like “corporeal and sartorial recalcitrance” and is associated with “retrogression, delay, and the pull of the past on the present.”30 It offers insight, however, into the potential excesses of history, in which drag functions “as a productive obstacle to progress, a usefully distorting pull backward, and a necessary pressure on the present tense.”31 In this formulation, the residue that Thomas describes functions as a marker of the presence of 1970s black lesbian feminist politics and lesbian feminism in general within contemporary iterations of black female queerness.

This insistence on 1970s black lesbian politics is especially radical because these politics, especially in their entanglement with the larger sphere of lesbian feminism, is usually positioned as essentialist and monolithic, antithetical to a queer sensibility that is imagined to be capacious and fluid. Though Lorde has been incorporated into a queer canon of sorts, her lesbian feminism has not been.32 This is the case even as womanism is explicit about its relation to lesbian feminism, which we can see in Alice Walker’s definition of the term: “Womanist . . . A woman who loves other women, sexually and/or nonsexually . . . [and is] committed to survival and wholeness of entire people, male and female.”33 Instead, its attention to racism and racial inequality is often (retrospectively) viewed as a source of friction within lesbian feminism.

Lesbian feminism is often positioned as what needed to be surpassed in order to arrive at the present. The 1970s is, therefore, as Clare Hemmings argues, “consistently marked as thoroughly unified in its aims, unreflexive in its theorizations, yet bold in its ambitions.”34 Further, in these characterizations of the 1970s, as Linda Garber notes, it is the figure of the lesbian feminist that bears the brunt of negative political representation. This is where the friction/residue of race comes in. Clare Hemmings writes that the lesbian feminist is stereotyped as “the flannel shirt androgyne, close minded, antisex puritan humourless racist and classist ignoramous essentialist utopian; [the lesbian feminist] often stands as a symbol for the limits of cross-class and cross-race alliances in second wave feminism.”35 In this scripting of the 1970s as passé, the presumption of whiteness and the charge of racism emerge as symbols of this out-of-time-ness. Being passé, however, also carries with it the implication that lesbian feminism was not interested in the sexual and, in fact, demonized most expressions of sexuality. In part, this perception is due to lesbian feminists’ focus on depathologizing lesbianism and moving it out of the realm of the sexological toward the territory of the everyday, attaching it to feminism, femininity, and family. Unfortunately, this emphasis on female homosociality was often coupled with a condemnation of pornography and S&M as antifeminist and harmful to women.

While Lorde’s focus on the erotic as a feminine resource is exemplary of this broadening of feminine desire—she highlights the nurturing and egalitarian aspects of femininity and argues that pornography emphasizes anti-sociality and inauthentic feelings—this charge of passéness enables people to assign some of Lorde’s ideas (about pornography, for example) to the realm of a disavowable lesbian feminism even as Lorde herself is often figured as a proto-queer theorist. However, this whitewashing of lesbian feminism neglects to take into account the potential value of Lorde’s (and other women of color feminists’) critiques. Rather than simply registering them as part of a moralistic anti-sex panic, we might see them as moving toward an intersectional analysis of sexuality in which the objectification of black women carries with it particular histories that complexify (or add friction to) any straightforward cultural condemnation or embrace of a sexual practice. Writing in this vein, Sharon Holland argues that “absenting these somewhat conservative black feminist opinions from the women of color intellectual project performs damaging work” by removing the specificities of race from discourses of sexuality.36 By drawing our attention to Lorde’s black maternal universe, Thomas leads us to consider the possibilities of generational friction anew, and friction, in turn, allows us to contemplate less discussed sensual intimacies.

By this, I mean that the residual and frictional come together most pointedly in Thomas’s emphasis on the clitoris. While Courbet’s The Origin of the World eschews any representation of the clitoris in favor of portraying the vagina as void, Thomas’s depiction of her clitoris is at once more anatomically correct and excessive in that it gestures toward the possibility of pleasure that is activated through friction rather than by penetration. Further, the clitoris’s designation as vestigial (or residual) organ—it is understood within evolutionary biology as developmentally homologous with the penis, but vestigial because scientists cannot specify an adaptive purpose—speaks to its inability to be contained within a universe of scientific objectivity.37

Thomas’s emphasis on the clitoris is in many ways emblematic of the 1970s feminist reclamation of the organ. Following William Masters and Virginia Johnson’s findings that the clitoris played a role in both clitoral and vaginal orgasms, feminists argued for a clitorally-based rather than vaginally-based sexuality. In an expanded version of her 1968 article, “Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm,” Anne Koedt wrote that disseminating physiological data would combat the previous misinformation about sexuality: “Rather than starting with what women ought to feel, it would seem logical to start out with the anatomical facts regarding the clitoris and vagina.”38 She celebrated Masters and Johnson’s findings of a universal clitoral orgasm and its promise for feminism. Sexual autonomy, specifically the image of an orgasmic woman, was a vital component of second-wave feminism. As Jane Gerhard writes, “A new generation of feminists envisioned sexual pleasure as empowering, as helping men become more human, and as a route out of patriarchal repression of the body. While pleasure did not mean the same thing to every woman, it nonetheless became synonymous, briefly, with liberation.”39 The centrality of sexuality to a particular radical feminist re-visioning of woman is evident in Koedt’s passionate disavowal of the vaginal orgasm. In 1968, she called upon women to take control of their sexuality: “What we must do is redefine our sexuality. We must discard the ‘normal’ concepts of sex and create new guidelines.”40 Koedt equated the vaginal orgasm with patriarchy because it catered to male ego, sexual pleasure, and sense of superiority while neglecting women’s desires. Insistence on vaginal orgasm was emblematic of the structural inequality between men and women; the clitoral orgasm illuminated the potential for equality and offered a way to conceive of women as autonomous in both sexual and nonsexual ways. Reframing orgasm around the clitoris allowed feminists, as Gerhard argues, “to claim a uniquely female form of sexuality that had the potential to transcend the narrow and pathologizing classifications of male experts.”41

The emphasis on the clitoral orgasm was especially important for lesbian feminists, some of whom argued that lesbianism was a form of uncorrupted femininity and that lesbians were not part of an economy of “female” sexuality. According to this logic, female sexuality was the province of women who engaged in sex with men and were part of a different sphere of desire and practice. As Monique Wittig writes in “The Straight Mind” in 1978, “It would be incorrect to say that lesbians associate, make love, live with women, for ‘woman’ has meaning only in heterosexual systems of thought and heterosexual economic systems. Lesbians are not women.”42 In arguing that a relationship to the phallus separates women from lesbians, Wittig articulates an important difference between lesbian sexuality and female sexuality. Alice Walker voices a similar logic when she narrates the experiences of an African American heterosexual woman who turns to the words of Lorde to teach her husband to stop objectifying her and to retrain his erotic impulses.43 Though these discourses differ in relation to the possible role for men and masculinity, all understand the clitoral orgasm as the foundation for a sexual practice that is not oriented toward penetration but that relies on surface stimulation of the clitoris.

Some of Thomas’s embrace of the clitoris indexes this feminist residue of self-determination. However, we cannot think about the clitoris without also acknowledging a sexological history that has scrutinized black female genitalia for signs of racial difference. This allows us to register anew what it means for Thomas to reject the aesthetics of the pornographic and sexological, which have historically turned to anatomy to naturalize black female difference. Jennifer Nash argues that these two discourses rely on “‘the desire to know and possess,’ to ‘know’ by possessing and possess by knowing. . . . Ethnography and pornography share a desire to know the ‘truth’ of other/Other’s bodies and a commitment to crafting a representational universe which contains the Other.”44 While Thomas’s painting refuses this will to knowledge through its aesthetics of surface, her emphasis on the clitoris cannot help but gesture toward racialized conceptions of sexual difference.

This is because among various sites where difference has been imagined to reside on the body, the clitoris has its own special place in the crossings of race, gender, and sexuality. In these schemas, black female bodies are situated as repositories of the less evolved, imagined as closer to nature, and rendered pornographic (which is to say eroticized and objectified). We are most familiar with this story as it has been narrated from the perspective of Cuvier’s fixation on the buttocks of Saartjie Baartman and the production of the myth of the Venus Hottentot, but late nineteenth-century anxieties about black female homosexuality and the myth of the black enlarged clitoris are also part of this pattern of ascribing physiological difference to blackness and mapping high libidos and indiscriminate sexual desires onto physiology.45 In the early twentieth century, describing a clitoris as enlarged was an announcement of sexual deviance. This means that doctors imagined that black women, poor women, and lesbians possessed especially large clitorises and that finding a large clitoris would foretell deviance to come.46 Siobhan Somerville describes the prevalence of this trend:

In an early account of racial differences between white and African-American women, one gynecologist had also focused on the size and visibility of the clitoris; in his examinations, he had perceived a distinction between the “free” clitoris of “negresses” and the “imprisonment” of the clitoris of the “Aryan American woman.” In constructing these oppositions, these characterizations literalized the sexual and racial ideologies of the nineteenth century “Cult of True Womanhood,” which explicitly privileged white women’s sexual “purity,” while it implicitly suggested African-American women’s sexual accessibility.47

Linking lesbian and black anatomies with deviance marked them as simultaneously “less sexually differentiated than the norm . . . [and] as anomalous ‘throwbacks’ within a scheme of cultural and anatomical progress.”48 It is important that we understand these intersections as part of the larger narrative of the un-gendering of blackness because it makes the black clitoris into a different sort of object altogether. Specifically, it makes the black clitoris both perverse and corrupting; it becomes an organ that seeks out other clitorises and vaginas for pleasure, and it detaches the black clitoris from the sphere of womanhood. We can register the meaning of this transformation when we see the ways that eroticism was projected into interracial scenes of homosociality, thereby promoting segregation as a means of guarding against the possibility of perversion.49 This narrative imagines that black clitorises are imbued with overt masculine sexuality—visualizable through the specter of enlargement, which went hand and hand with the sexological imagination of the black clitoris as an organ used in penetration.50

Thinking with the clitoris, however, also brings us toward tribbing, a sex act comprised of friction. While tribbing has a long history, some of which Valerie Traub positions contra to hetero/homo binaries, Jack Halberstam locates the practice within an economy of female masculinity.51 He writes, “Tribadism, because it seemed to resemble intercourse in either its motion or its simulation of penetrative sex, was often linked to female masculinity and to particularly pernicious (because successful?) forms of sexual perversion.”52 Although this masculinization of the practice might allow us to think about tribbing as a racialized act, here, I am interested in its contemporary association with the 1970s and 1980s, as Linda Williams reminds us when she describes its aesthetics: “the often decorative, nonpenetrative nature of much lesbian sex in heterosexual pornography has long been reviled by contemporary lesbians who deem themselves more ‘authentic’ than previous generations. Hence the vehemence toward scissoring and reverse cowgirl, though I would point out that these were once quite popular, even idealized, positions in ‘explicit’ lesbian pornography made by and for lesbians in the mid-1980s.”53 Because it is outside the logic of penetration, tribbing exceeds many understandings of what constitutes sex and therefore stands outside of it. Historically, this means queer women looking to reclaim lesbian sex and eroticism from this lacuna of homosociality emphasized the eroticism of penetration with dildos, fists, and tongues, and distanced themselves and their practices from the surface economy of tribbing, which registered as passé and inauthentically—which is to say, anachronistically—queer.

Tribbing, then, is a practice that shows us the generative possibilities of friction—both through the reclamation of the passé-ness of lesbian feminism and by working with the clitoris as residual and racialized organ. In reading Origin of the Universe 1 in relation to tribbing, I argue for understanding a queer present for the practice and a way to reread its relation to friction. The reluctance to claim tribbing as part of a contemporary queer set of sexual practices while simultaneously deploying its symbol as a sign of queerness (I am thinking here of the popularity of the scissors icon as a shorthand for queer sex) speaks to a difficulty in understanding the role of surface and friction in thinking about sexuality. In historical terms we see this in the apprehension that surrounds 1970s and 1980s black lesbian feminist and womanist discourses on sex—especially since they emphasize the vulnerability of bodies within racist and patriarchal hierarchies. But in hinting at tribbing and the pleasures of friction, we also return to a theorization of the clitoral orgasm and the frictional pleasures of mutual vulval contact. Thinking about sexual relations as a matter of two surfaces coming together is both a matter of friction activating nerves and leading to orgasm and a subversion of the objectifying regime of the visual in favor of that of the tactile. This is because there isn’t much to see. Both surfaces are laboring frictionally toward a visually unmarked end. In many ways this activation of the surface further reifies an economy of opacity in relation to sexual pleasure. Instead of figuring vagina as void, however, what becomes more mysterious is the connection between surfaces and pleasures. Perhaps this is why these tribbing scenes have become popular among heterosexual men: they represent (or at least allude to) the pleasures of the surface, which do not translate visually.

This is part of the excess of tactility that surfaces generate. Tribbing negates histories of objectification through excess, often to the point of orgasm. In Origin of the Universe 1, I locate this frictional excess as something that threads through the rhinestone and the clitoris by way of a resignification of the 1970s. Thomas activates this 1970s residue by engaging with womanism and its emphasis on thinking about multiple forms of marginalization in order to disrupt simplistic ideas of pleasure and power. These critiques, in turn, mobilize the possibilities of opacity that inhere in the unrepresentability of tribbing. This is territory that brings us back to Lorde, who, Sarah Chinn writes, “reimagines and represents lesbian sexuality in ways that profoundly challenge her readers, as something situated on the surfaces and in the crannies of the body, as floating up into nostrils and ears, as myrrh: a fragrant, viscous scent absorbed into the skin.”54 With this statement, we suddenly find ourselves in the excesses of surface sensation that tribbing offers; we are in its sweat, surface, and funk. This is the other side of 1970s; it offers brown jouissance in a whiff of the “bodies and pleasures” about which Foucault waxed rhapsodically. Here, we remember that one of the lures of the surface is that it offers a space to think toward brown jouissance and its alternate choreography of pleasures, relationality, and self-making.

Self-Love, Masturbation, and Impersonal Narcissism

To think the surface, however, is also to traffic in the superficial and narcissistic, which are the categories that we typically use for thinking about surface in relation to selfhood. However, I do not see the operations of self-making that Thomas displays as registering within the realm of solipsim. Thomas’s mobilization of rhinestones destabilizes the idea of a coherent, knowable self through fragmentation and cover. Likewise, her positioning of women of color as the origin of the universe produces a plural self attentive to the frictional temporalities of generational time and the possibilities of resignification. Here, I theorize these relationships to surface and self as a way to understand Origin of the Universe 1 as presenting the self-portrait as a vehicle for self-love, which, in turn, is an alternate framing of narcissism and superficiality as political practice.

While Thomas veers away from authenticity, interiority, and even individuality, her insistence on presenting—nay, flashing—a self that is objectified and relational speaks to brown jouissance’s mobilization of flesh’s liquidity. It also, importantly, speaks to the pleasure that liquidity might index. Here, I interpret the rhinestones as a record of a practice of self-love. In reading the rhinestone as a material remainder of Thomas’s pleasure, I argue that they remind us of physical aspects of Thomas’s sexual excitement in addition to illuminating a version of self-care that is tethered to pleasure. While Courbet’s model’s pleasure is rendered mysterious, Thomas uses the rhinestone to show us how we might consider her pleasure as present and material even as it remains opaque. Hence, I see the rhinestone as part of a formulation of liquidity in that they gesture toward interiority and agency while refusing that the flesh settle into subject or object. Thinking the rhinestone as a trace or residue of Thomas’s wetness and excitement allows us to hold violence, excess, and possibility in the same frame. Even as the source is ambiguous, the idea that rhinestones might offer a record of pleasure—pleasure that is firmly constituted in and of the flesh—shows us a form of self-possession. This self is not outside of objectification, but its embellishment and insistence on the trace of excitement speaks to the centrality of pleasure in theorizations of self-love.

Within the register of black queer pleasure, this concept of self-love finds an echo in Lorde’s theory of the erotic. Lorde describes the erotic as “a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings” and as “an assertion of the lifeforce of women; of that creative energy empowered.”55 The erotic is both something that belongs to individuals and something that cannot be contained by them. In this way, Lorde’s version of the erotic can be understood as a particular response to the trauma of racism and discrimination, which prevents the formation of community among African American women. Racism produces self-hatred and anger and must be met with self-love. In “Eye to Eye” Lorde writes, “It is empowerment—our strengthening in the service of ourselves and each other, in the service of our work and our future—that will be the result of this pursuit. . . . I have to learn to love myself before I can love you or accept your loving.”56 The erotic, for Lorde, is a call for self-care and community to repair the damage done by patriarchy and racism and to formulate ways of moving beyond those systems. Reading Thomas’s investment in pleasure and desire as a version of Lorde’s erotic allows us to dwell on the importance of self-love as a politics.

In her analysis of black feminism’s relationship to the politics of love, Jennifer Nash argues that the specificity of love within black feminist thought in the 1970s and 1980s has to do with the centrality of the self.57 Nash writes that this form of self-love is a departure from love as “simply a practice of self-valuation” and that it is, instead, “a significant call for ordering the self and transcending the self, a strategy for remaking the self and for moving beyond the limitations of selfhood.”58 In describing womanism’s conception of self-love, in particular, Nash emphasizes that this reorganization of self is where politics emerge. To use the terms that I have been using in this chapter, self-love is what produces the possibilities of frictional engagement. Nash writes:

Walker’s womanist subject “loves herself. Regardless.” The italicized “regardless” reveals that self-love is absolutely essential, that it persists in spite of everything else. Although Walker’s call to self-love is certainly an “artful advocacy of unconditional love that starts with our acceptance of ourselves as divinely and humanly lovable,” it is also far more. With “regardless” modifying “loves herself,” Walker suggests that self-love stands at the heart of the womanist project, and functions as a prerequisite for other kinds of humanistic, sensual, erotic, and spiritual loves that the womanist embodies. Self-love, it seems, is the only love that must always exist; it is the love that enables the other loves Walker’s womanist embodies, engenders, and relishes.59

Nash’s reading of Walker positions self-love as something necessary for politics and something that takes work. Self-love is not necessarily restricted to pleasure; it requires “ethical management of the self,” “pushing the self to be configured in new ways that might be challenging or difficult.”60

This prioritizing of self-love for the production of politics and the simultaneous eschewing of the romantic leads us to a consideration of the masturbatory for several reasons. First, it reinforces the link between pleasure and the political practice of self-love by emphasizing the importance of relating to the self. Second, it brings us back to tactility’s role within the practice of self-love. In particular, this tactility highlights the role of embodied knowledge production. Knowing how to manipulate one’s body to produce pleasure was considered an important feminist step in understanding the capacity of the body and in freeing oneself from the tyranny of the medical establishment. We especially see this connection in Our Bodies, Ourselves, a collaborative project started in 1971 by members of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. The collective urged women to touch themselves to gain a better understanding of their bodies and to find freedom from patriarchal norms. Women were encouraged to explore the surfaces of their body in addition to examining themselves in mirrors: “We emphasize that you take a mirror and examine yourself. Touch yourself, smell yourself, even taste your own secretions. After all, you are your body and you are not obscene.”61 This project of sensual knowledge production reemphasizes the dimensions of knowledge that the visual occludes. To touch oneself—to understand how to use touch to bring pleasure to the self—is an important political act. This is yet another way of reading Thomas’s use of the rhinestone: After all, why separate orgasmic pleasure from pleasure in the decorative, and why give it priority? From this perspective, I read Origin of the Universe 1 as a continuation of feminist projects to use tactile explorations of one’s body as a technology for subverting the scientific/pornographic gaze’s will to know and empowering the self. This, in turn, allows us to read Thomas in relation to Lorde’s description of masturbation as a healing practice. In The Cancer Journals, Lorde chronicles her use of masturbation as a way to find a connection to herself and others:

November 2, 1978 How do you spend your time, she said. Reading, mostly, I said. I couldn’t tell her that mostly I sat staring at blank walls, or getting stoned into my heart, and then, one day when I found I could finally masturbate again, making love to myself for hours at a time. The flame was dim and flickering, but it was a welcome relief to the long coldness.62

Masturbation is a practice of radical self-love. It brings Lorde closer to the erotic and the political.

In fusing radical self-love with the masturbatory, we can also begin to see how the erotic might allow us to rethink narcissism as political. Here, I put Lorde and Thomas in conversation with Leo Bersani and Adam Phillips, who conceptualize ethical relation as a form of impersonal narcissism.63 Impersonal narcissism is built upon the finding of sameness rather than difference—though we might question whether all dimensions of difference are given equal weight in this schema. They write, “The self the subject sees reflected in the other is not the unique personality vital to modern notions of individualism.”64 When individuality is less important than commonalities, difference registers as supplemental, and relation relies on narcissism. Bersani writes, “The experience of belonging to a family of singularity without national, ethnic, racial, or gendered borders might make us sensitive to the ontological status of difference itself as what I called the nonthreatening supplement of sameness.”65 What Bersani and Phillips suggest is that if we attach to sameness through narcissism, we are free to lose ourselves in the Other because we do not see our individuality at stake. This, in turn, opens toward an alternate formation of ethics. While Bersani and Phillips do not describe this narcissism as a form of radical self-love, it has much in common with Lorde’s version of the erotic in that it begins with the self and extends that self outward. While Lorde emphasizes the importance of starting with individual selfhood, her version of the erotic is, above all, a mode of bringing people together—despite their differences. Specifically, Lorde emphasizes the importance of individual empowerment for collectivity on a multigenerational scale: “The aim of each thing which we do is to make our lives and the lives of our children richer and more possible.”66 The individual is where things begin, but the erotic’s politics are tied to the production of an affective community—a community bound together by feeling and politics rather than surface similarities. Lorde writes, “The sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared between them, and lessens the threat of their difference.”67 The erotic, then, is “an assertion of the life force of women; of that creative energy empowered”; it is both something that belongs to individuals and something that cannot be contained by them.68

This emphasis on sameness becomes a mode of thinking with others because it invites a contemplation of the self as unbounded and plural. This is a plurality that Thomas invokes in multiple ways. We see it in her response to a query about whom she sees in the mirror: “It’s always me. Sometimes it’s also my mother, my grandmother, or my great-grandmother,” and we see this in her decision to make Origin of the Universe 1 a diptych.69 Its pair, Origin of the Universe 2 (2012), is a portrait of Thomas’s then-wife, Carmen McLeod. Thomas describes the paintings as “a sort of call and response, dealing with the nature of sexuality on a different level, romanticizing the nature of relationships and intimacy—and also having this connection with a black body in relation to a white body.”70 Although Thomas describes the paintings as a form of call and response, reading through the lens of impersonal narcissism and radical self-love we can also see that there is an emphasis on sameness with McLeod: rhinestones, clitoris, spread legs are present in both. The skin tones are different, but thinking about their pairing through the lens of similarity, we can imagine that Thomas has produced a plural self-portrait that begins from the place of self-love.

Figures 2.1 and 2.2. Mickalene Thomas, Origin of the Universe 1 and Origin of the Universe 2, 2012. Images and original data provided by Larry Qualls Photographer: Larry Qualls © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

This search for sameness not only has echoes with Lorde’s erotic, but also with Walker’s womanism, which supports a love “that embraces everyone for the purposes of healing, change, and liberation.”71 Yet, in thinking with brown jouissance, it is important to remember that this possibility of finding sameness (coalition) begins with locating the self, not only in relation to others, but in relation to violence. Just as Nash reminds us that “womanism’s universality is rooted in black women’s particular experiences,” Thomas’s embrace of the possibilities of self-love begin with the centering of the black queer body.72 This is not about segmenting along lines of identity, but about understanding the ways that particularity is rooted in the politics of knowledge production and is not merely a surface structure. Beginning with a black queer female body offers a reorientation of relation and politics, even as it enables an embrace of plurality. It is the origin of the universe, after all, and through this body, we can trace histories of oppression and objectification in addition to refusal, love, and the sensualities of surface.