4

Performing Witness

Voice, Interiority, and Diaspora

A young black woman stands in profile; she is bare-chested and unsmiling. There is a continuous line between the shadows on her back and her closely cropped hair. The image is bathed in red. White text overlaid on the photograph reads, “You became a scientific profile.” In an adjacent photograph, an older black man with silvery hair gazes impassively at the camera in an image that highlights his wiriness; the textual overlay on this photograph reads, “A Negroid Type.” These images are drawn from the Louis Agassiz collection at Harvard’s Peabody Museum.1 While Agassiz commissioned the daguerreotypes as part of his efforts to produce a visual taxonomy of physical types and support his theories of the inferiority of black people, Carrie Mae Weems incorporates them into her 1995–1996 photographic series, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, as an illustration of the links between the commodification of blackness and the visible wounds of race. Yet in Weems’ series, which consists of thirty-four nineteenth- and twentieth-century photographic images culled from various archives, there is also something else, something that enables us to think about brown jouissance in relation to voice and the project of witnessing.

Thinking brown jouissance in relation to the voice reveals the tension between the materiality of the body and the ineffable qualities of interiority. Voice, after all, is that which exceeds mere speech. Its granulations are products of movement, bodies, and histories—what I describe in relation to Weems’s series as a version of diaspora—especially as it indexes a beyond. In his description of what he calls “jouissance beyond the word,” Néstor Braunstein writes that “it is impossible to objectify, impossible for the parlêtre to articulate. It is this jouissance which prompts Lacan to say, ‘Naturally, you are all going to be convinced that I believe in God.’”2 Voice, then, links physicality to spirituality. To think voice in relation to a series of photographs, however, is another thing altogether, but voice comes through in the way that this series highlights Weems’s performance of witnessing. This witnessing inheres in her tinting of the photographs—red mostly, but also blue—and her application of a textual overlay. Through these acts she amplifies the possibility of locating voice within the photographs, not only showing us the jouissance that lies beyond the word, but transforming these photographic objects into portraits of interiority, as well. Weems brings forth the voices of diasporic ancestors so that the relationship between spirituality and interiority is made manifest even as these photographs illustrate a history of black bodies as commodities. It is in Weems’s interpretive tug between visual objectification and the possibilities of voice that brown jouissance lies.

Objectification, Commodification, and an Archive of Black Woundedness

From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried was commissioned by the Getty Estate in Los Angeles as a companion piece to their 1992 exhibition, Hidden Witness, which depicted images from Jackie Napolean Wilson’s collection of photographs of African Americans immersed in daily life throughout the nineteenth century. In his description of the image that gives the show its name, Wilson writes, “When I first saw this daguerreotype, it was the warmth of the family setting and the beauty of the land that first caught my attention; later I saw this man forlorn with shovel in hand leaning against the tree. . . . This slave gardener made the scene himself. He was the ‘hidden witness’ who saw this picture being created and was a witness to life at that time, and remained a testimonial to this day.”3 Hidden Witness recognizes the underacknowledged labor that African Americans performed as slaves or servants, displacing the ideology of the naturalized white family unit and highlighting its dependence on racialized labor. Wilson’s project is recuperative: it brings together unexpected archives to consolidate images of quotidian black life, thereby allowing the viewer to consider the humanity of the subjects, who are often caught off guard and appear lost in thought, while drawing our attention to the labors of race.

In response to Wilson’s eclectic, dreamy archive and its hints of racial uplift, Weems plays the more negative side of the affective register. As Weems explores what it is to witness, her installation summons grief, guilt, empathy, and sympathy in ways that both mask and unmask her racialized subjects. Instead of captions bearing names or identities, Weems’s reprints show us objectified bodies, largely from nineteenth-century sources. In Weems’s focus on the visual economy of race and its relationship to objectification, she illuminates Nicole Fleetwood’s argument that “the notion of rendering/rendered is crucial to the formulation of blackness and blacks as objects and subjects of visuality and performance.”4 Writing further, Fleetwood argues that “the visual manifestation of blackness through technological apparatus or through a material experience of locating blackness in public spaces equates with an ontological account of black subjects. Visuality, and vision to an extent, in relationship to race becomes a thing-in-itself.”5 The histories of medicine, anthropology, and surveillance reinforce this claim because these disciplines rely on producing difference as visible and therefore quantifiable. For example, Simone Browne’s recent work on re-centering blackness to demarcate difference in surveillance studies begins with a comparison between slave ships and Bentham’s famous panopticon.6 In these sets of arguments, we see that technologies of visual representation, including photography, are deeply imbricated in histories of consolidating race as visually knowable, transforming photographic subjects into specimens—examples of types rather than individuals. By delving into the photographic archive, Weems is explicit in her summoning of this history of visual objectification.

From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried presents this violence in a doubled fashion, however. Weems shows us that there is violence inherent to the medium of photography, while also presenting images that speak to the violence (past and present) of slavery.7 Part of what is at stake in Weems’s series is the illustration of the delicate contours of the relationship between blackness and enfleshment. Here, we follow Hortense Spillers and her articulation of the relation between blackness, flesh, and rupture. Spillers argues that flesh is what bodies become through the violence of the transatlantic slave trade, but this flesh, she cautions, is seldom intact; it is “seared, divided, ripped-apartness, riveted to the ship’s hole, fallen, or ‘escaped’ overboard.”8 These tears, and the discourse of woundedness, become scripted as precultural, rendering blackness vestibular and spectacular in its difference.

Because Weems’s series plays with the wound, it activates cycles of spectatorical pleasure and empathetic shame, thereby allowing us to uncover the affective dimensions of enfleshment, the space where relations between racialization and gendering become written on the body through emotion. The spectacle of the black body in pain mobilizes empathy and sympathy, but also passivity.9 This is to say that black pain induces sentiment, rather than action. In this understanding of race through visual dominance, we see a crystalization of a mode of interraciality in which blackness is related to woundedness and whiteness is linked with passivity and innocence—one cannot even begin to imagine acting. In her analysis of white innocence, Robin Bernstein argues that these images of woundedness also lead to a perception that black bodies can tolerate more pain and should be subjected to this violence. As evidence of this, Bernstein describes dolls as scriptive things that elicit racialized performances of violence. Bernstein writes, “Children of all races committed violence against dolls of all colors, but white girls specifically targeted soft black dolls for ritualistic and exceptionally violent abuse, which the dolls, of course, submissively endured.”10 In this violent play, blackness permits objectification and harm. In part, this is because violence is not imagined as producing pain—hence the production of white innocence as a lack of ability to conceive of black pain as well as insulation from white guilt. Black pain also hovers around projects of liberation, however. In her analysis of black feminist discussions of sexuality, Jennifer Nash argues that despite their aims to produce narratives of sexual liberation and possibility, many black feminists are still caught up in responding to these legacies of pain, especially in relation to representation: “A vibrant and varied archive that contains different theories of representation still manages to collectively perform the black female body as an injured site, producing an archive that is structured by a ‘grammar’ of woundedness.”11

It is the explicit depiction of woundedness alongside the photographic and affective violence of spectatorship that make Weems’s piece so complex. Her series summons the multiple forms of violence that have visited black Americans while also displaying the passivity of white Americans. Further, the title announces shame and sorrow at these spectacles of racist violence in relation to the act of crying: “From here I saw what happened and I cried.” We have many options for understanding these tears: as grief? Humiliation? Shame? Guilt? We might even use the title to understand the series in relation to racialized sentimentality as a genre.12 In her analysis of the series, Jennifer Doyle notes that this mobilization of sentiment invites collective—perhaps even national—mourning at the history of slavery and of racism. She writes, “From Here I Saw might thus be read as indexing anger, frustration, and exhaustion, a depression by dint of routine: theft, exploitation, appropriation, resistance, grief, mourning, and recovery—followed by the requirement that the artist produce that cycle within her work.”13 The tears that Weems’s series invokes invite us to critique the regimes of visuality that have objectified and harmed black people and to mourn the ways that we have been implicated within this system either as objectified bodies or as passive spectators; the textual “you” that circulates above most of the images allows for this shifting identification. In this way, the installation manipulates our affective response through either one or both of these circuits of bad feelings. Those who suffer are stuck in a cycle of violence and harm, while those who watch are rendered passive. Against the narrative of uplift hinted at in Hidden Witness, Weems’s work suggests the impossibility of moving beyond that frame, prompting some, including Doyle, to ask whether Weems herself is participating in the same problematic dynamic that she unveils: “At what point does witnessing switch from being a point of resistance to being a point of collusion? How does one know the difference—is it a matter of how we look at something, how we feel about what we are looking at? What is the relationship between one and the other?”14 From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried appears to name the collective feeling that the series generates without giving us a way to think outside of that framework. As spectators, we remain stuck in the temporality of grief and its guilt, shame, and sadness.

But when we turn to Weems’s comments on the series, we gain a different perspective. Weems argues that while she is “trying to heighten a kind of critical awareness around the way in which these photographs were intended,” she is also working to “give the subject another level of humanity and another level of dignity that was originally missing in the photograph.”15 It is in this project of giving voice to her photographic subjects that I see Weems illuminating the possibilities of brown jouissance. She does this first by performing witness—rather than spectatorship—through her juxtaposition of text and image to produce interiority and, second, by drawing attention to the way that photography functions as a technology of reproduction and kinship, thereby altering our understanding of mothering.

Voice, Tears, and Interiority

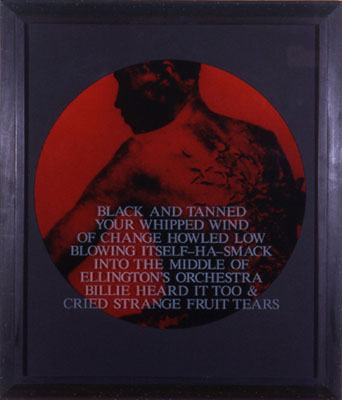

One of Weems’s strategies for returning humanity to the subjects in the photographs is to announce the opacity of their interiorities while simultaneously addressing them by the use of “you.” This “you” is capacious, inviting both spectators—especially those who might identify with the photographs—and the long dead photographic subjects into dialogue with Weems. One particularly jarring example overlaid on a man’s scarred back reads:

Black and Tanned

Your Whipped Wind

of change howled low

blowing itself-ha-smack

into the middle of Ellington’s Orchestra

billie heard it too &

Cried Strange Fruit Tears.

Here, we see that “you” can mean a lot of different things. In speaking to museum spectators, we can imagine that “your whipped wind of change” invokes the incomplete nature of civil rights movements in its suggested conflation between the wound depicted in the image and the contemporary viewer’s experiences of racism. This allows the viewer to imagine that it is his or her body in the frame. Through apostrophe, Weems also summons interiorities that have historically been ignored—those of the people in the photograph. In speaking to them, however, Weems is not asking that we substitute their interiority for our own, but that we listen for their voices. It is significant that she does this by positioning them alongside Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday, which shifts the register of black pain away from the visual toward the opacity of sound. This allows us to consider voice in relation to interiority. The richness of this interiority is demonstrated, in turn, by how Ellington and Holiday signify. Here, I turn to Fred Moten’s description of Holiday’s voice:

Figure 4.1. Black and Tanned Your Whipped Wind of Change Howled low blowing itself-ha-smack in the middle of Ellington’s Orchestra billie heard it too & Cried Strange Fruit Tears. ©1995 Carrie Mae Weems.

The grained voice engrains, the sign of the mouth, which is the birth, the sign of a kiss, reading you like an analyst reads the signs; here that reversal, where the listener oscillates between the analytic positions, is now such that the listener is without knowledge and waiting on Lady to lecture, to free-associate. . . . She’s on another thing, another register of desire. And that grained voice elsewhere resists the interpretation of the audience where the analytic positions are exchanged.16

In Moten’s evocation of Holiday’s interiority, we come toward opacity. Moten argues that Holiday’s singing positions her interiority as unknowable, while prompting self-reflexivity in the listener. In other words, her singing announces an interiority, while leaving it to others to imagine themselves in relation to it. Further, by describing Holiday’s voice as grained, Moten brings Roland Barthes into the conversation—specifically Barthes’s argument that the grain of the voice, “the materiality of the body speaking its mother tongue” brings “not just the soul but jouissance.”17 For Moten, the materiality of Holiday’s body does not just index pain (though that is present), but speaks to spirituality and pleasure, too: “She cuts literature like St. Theresa, with muteness and grain.”18 Brown jouissance, voice, and opacity come together in these lines. What Weems tells us with her juxtaposition of image and text and summoning of the sonic is that black interiority is found in the cracks around the visual and that within the register of the sonic, this interiority should be imagined through a prism of relationality and opacity rather than through a mandate of transparency. We are in the space of the something else that Weems creates from Agassiz’s photographs.

Weems further distances herself from transparency by displacing her own interiority from the series. The titular “I” is not Weems, but Wilson. The title, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, is actually a quotation from one of Wilson’s captions in Hidden Witness. While we can understand this phrase through the spectacularization of the wound and the temporal stagnation of the black photographic subjects whose images she has enlarged and tinted—all of which are more conventional readings of Weems—what does it mean for Weems to use this phrase as her title? I read Weems’s citation of Wilson as a strategic mode of creating distance in order to reveal the opacity of interiority. It also, however, signals that she is doing something different with the concept of witnessing. Instead of portraying witnesses, Weems performs witness through her emphasis on the relationship between her and the images and in the way that she acts as a mediator between the images and the installation spectators. This performance of witness is about fleshiness and relationality.

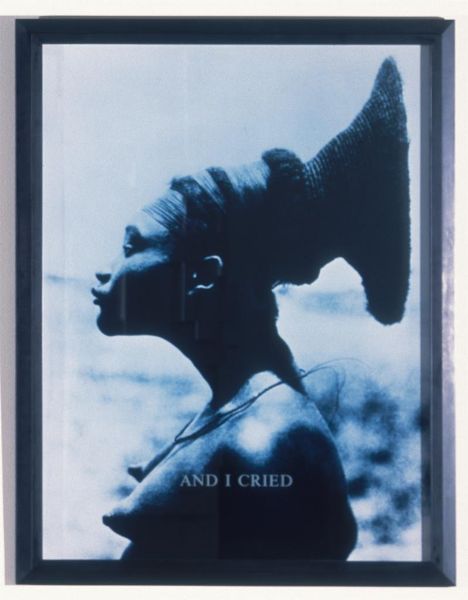

Witnessing announces Weems as a self who exists profoundly in relation to others. She produces her own opacity by juxtaposing text and image so that the relation between her, these photographic ancestors, and museum spectators becomes complicated. We are presented with voices, but we do not know whose. Are we listening to Weems, the people in the photographs, or an unannounced voice from elsewhere? Thinking with voice and witnessing is important because it highlights the elements of fleshiness that come through Weems’s performance of witness. By witnessing, Weems is actively listening to the photographs—challenging the idea that photography is only about the visual and illuminating Moten’s argument that photographs “in general bear a phonic substance.”19 Further, this “I”—which we imagine to be Weems’s flesh—allows us to think of Weems’s interiority as infusing the installation through her manipulation of the prints, which are not only enlarged but tinted blue or red, perhaps suggesting rage, sadness, or any number of emotions. It is significant that the two blue-tinted images, “From Here I Saw What Happened” and “And I Cried”—which depict an African woman whose gaze is directed toward the rest of the series in “From Here” and back over it in “And I Cried”—bookend the show. In addition to gesturing toward the diasporic, as the only images that are overlaid with an “I” they further illustrate the distance between the images that Weems has resignified—“A Scientific Type”—and her own interiority.

Weems’s circumspect invocation of tears is also an important part of this simultaneous display of fleshiness and opaque interiority. If Weems is crying, might we find a kinship between these salty emissions and photography’s liquidity? Perhaps crying in the darkroom offers its own politics? I come to this fusion of photography and crying by way of imagining the alchemy behind these scenes of fleshy capture. Photography’s techniques of making the visible permanent through the chemical capture of light seems an apt counterpoint to the tear’s imbrication within racialized discourses of woundedness. Both traffic in fixity and fiction. Here, the ambiguity of tears is an asset. Even as they illuminate the violent ruptures caused by colonial histories, they offer a way to see beyond woundedness. Further, in perceiving “the tears” as evidence of Weems’s witnessing, we move into the alchemical—the space of transformation where flesh might shift from wound into something else. Specifically, I argue that these tears transform photographs of objectification into portraits—illustrating the mobility that underlies liquidity.

Figure 4.2. Carrie Mae Weems, “And I Cried,” Baltimore Museum of Art. ©1995 Carrie Mae Weems.

Liquidity, here, reveals something about the relationship between affect, flesh, and the possibility of expression. More specifically, it leads us to think with the face—the origin point of tears. While we do not actually see anyone in tears, it is through a consideration of the tear that we can restore interiority to the subjects of these photographs. By transforming these photographs into portraits, these images become people who might cry or laugh or reveal their interiority in countless possible ways. For Brian Wallis this transformation occurs because Weems’s subject position allows her to relate to those in the photographs as individuals rather than types. He writes, “She saw these men and women not as representatives of some typology but as living, breathing ancestors. She made them portraits.”20 In thinking with this difference through the images that Weems uses from the Agassiz archives, for example, the suggestion that these are portraits rather than depictions of specimens draws our attention to hints of personality in the crevices of the face, emotions in the eyes, affect in the posture. Instead of registering these prints as examples of African Americans during slavery or in terms of measurement or form, viewing them as portraiture suggests affect. In this we see that Weems’s transformative (and tinted) tears have shifted our attention away from the affect that is projected onto the images and toward the possibility of understanding these images as expressive.21

Expressivity also allows us to think through the tears that we do not see. The invocation of a crying face—whether it is Weems’s or someone else’s—and Weems’s denial of the spectatorial pleasure of a crying face, which might lead to catharsis or an imagined absolution of guilt, force us to dwell on the interiority hidden beneath these violently produced images. This ambiguity allows us to see the importance of thinking with opacity. In this Weems also issues a subtle rejoinder to the concept of blackness as a “hidden witness”; in her series, not only are these portraits of black people not hidden within the cloak of white normativity, but they and their expressivity are essential to the performance of witnessing. They are front and center—an emphasis amplified by Weems’s use of black matting around the images to focus our attention on the center of the frame. This focus on the photographic forces us to think with the images of black people in pain to find something new, something not overly signified. In Barthes’s parlance we might ask what is the punctum? What affectively pricks us?22

Instead of tears, what we see is the complex relationship between surface and depth and subject and object. How we perceive what is going on in the images depends entirely on perspective, but the possibility of ambiguity, which is where I locate interiority, is crucial to allowing flesh to signify differently. This is a space where many things are possible. It is the space where Tina Campt and Kevin Quashie locate the quiet. Campt writes that “quiet is a modality that surrounds and infuses sound with impact and affect, which creates the possibility for it to register as meaningful.”23 For Campt, the quiet is part of an “everyday practice of refusal.”24 Likewise, Quashie argues that quiet enables us to imagine a wider range of possibilities for blackness and to begin to theorize black subjects. He writes, “Quiet . . . is a metaphor for the full range of one’s inner life—one’s desires, ambitions, hungers, vulnerabilities, fears. The inner life is not apolitical or without social value, but neither is it determined entirely by publicness. In fact, the interior—dynamic and ravishing—is a stay against the dominance of the social world; it has its own sovereignty.”25 Quashie’s insistence that interiority allows for a space separate from domination allows us to think about both the value of ambiguity and the form of political work that Weems’s installation does. Interiority is the space that Spillers demands black intellectuals take up when she urges a reconsideration of psychoanalysis. She argues that interiority can act as a balm against the sociological construction of subjectivity, which Fanon argued vociferously against and which activates pernicious circuits of sentimentality. Spillers describes interiority as “persistently motivated in inwardness, in-flux, it is the ‘mine’ of social production that arises, in part, from interacting with others, yet it bears the imprint of a particularity.”26 Traditionally, interiority is expressed through speech, but as Spillers points out, “To speak is to occupy a place in social economy, and, in the case of the racialized subject, his history has dictated that this linguistic right to use is never easily granted with his human and social legacy but must be earned, over and over again, on the level of a personal and collective struggle that requires in some way a confrontation with the principle of language as a prohibition.”27 The denial of interiority and speech is, after all, part of the process of enfleshment. Voice, that sonic space of expressivity that exceeds language, signals interiority while remaining opaque. This is what makes Weems’s use of apostrophe radical: it hails a quiet, but not silent interiority.

Refracted through the ambiguity of the quiet and its “level of intensity that requires focused attention,” these photographic voices are amplified through Weems’s performance of witness.28 This illumination of voice also draws attention to all of the ways that flesh evades technological capture. Importantly, Michelle Stephens argues that the gap produced by fleshiness is one that centers relation. Rather than focus on the question of authenticity or liveness, the voice activates circuits of openness toward the other. She writes, “Lacan privileged voice, sound, and the ear as important aspects of, as he termed it, an invocatory drive. This was precisely because of the ways in which, unlike the image and the gaze, the circuit of desire to hear the self, to hear the other, and to be heard as the other hears us, can never be completely closed.”29 In using Weems to think with the relational dimension of voice, however, we gain access to long-dead ancestors in a way that exceeds the portrait.30 It is not just that these images have their interiority restored; their identity as a bounded series also allows us to think about the self as collective and diasporic. This Weems achieves by drawing attention to photography as a technology of reproduction and mothering.

Making Kin: Diaspora, Affect, and Mechanical Reproduction

In arguing that Weems presents selfhood as collective and diasporic, I also argue that Weems allows us to see the ways in which performing witness is a form of gendered labor. This restoration of gender operates against the ungendering that traditionally accompanies enfleshment, what Saidiya Hartman describes as the fungibility of blackness, which is part of the enslaved’s transition into the commodity.31 This re-gendering is part of what emerges when we consider the work of photography in terms of reproduction, which, in turn, allows us to see that Weems’s performance of witness is also one of mothering in that it produces new forms of kinship.

The ungendering that accompanies the processes of enfleshment is achieved, according to Spillers, through slavery’s violation of the norms of the psychoanalytic family. The emergent family structures collapsed the law of the Father with normative whiteness and made maternity synonymous with reproduction and labor, thereby making mother and father impossible positions for the enslaved to inhabit and leaving the Oedipal family structure unachievable. These psychoanalytic consequences left blackness outside of the symbolics of gender. Spillers writes, “In other words, in the historic outline of dominance, the respective subject-positions of ‘female’ and ‘male’ adhere to no symbolic integrity.”32 Under these conditions of powerlessness, “we lose at least gender difference in the outcome, and the female body and the male body become a territory of cultural and political maneuver, not at all gender-related, gender specific.”33 This unmaking of gender has deep and important consequences. Most immediately, it threatens the possibility of subjectivity. This difficulty emerges most potently when we read Spillers in conjunction with Judith Butler. In Gender Trouble, Butler argues that even as gender is not an inherent attribute of the subject, it is integral to its formation because it enables legibility. Gender, Butler argues, is the product of repeated, stylized acts that are part of historically produced binaries and the heterosexual matrix.34 Since these performances of gender lie at the core of the subject’s identity, Butler articulates a subject who is perpetually in the state of becoming male or female. To exist in a state of un-gendering, then, denies the possibility of subjectivity. This difficulty around subjectivity is part of why I argue that From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried restores interiority not subjectivity.

Indeed, we see this instability in Weems’s reprints of Agassiz’s photographs of bare-chested slaves, which do not adhere to the conventional gendered divisions of portraiture and present both male and female slaves in the same way. Weems’s use of “you” throughout the series also serves to preserve the instability of gender even as the images themselves—a female nude presented as a “playmate for the patriarch” while the subsequent image of an older woman holding a white child reads “and their daughter”—expose the gendered division of labor. Further, if we consider Weems’s use of photography as a technology of reproduction—in its multiple meanings—we can see a space for re-thinking mothering. Here, I argue that we think Weems’s photographic enterprise and its relation to liquidity as not only about the provocation of chemical reactions and interiority but also as a form of reproduction and kinship. This is to say that Weems’s performance of witnessing creates important connections between Weems and the photographs that she reproduces. This connection is not just about the infusion of interiority, but about the constitution of kinship wherein linkages are wrought through voice, darkroom chemicals, and flesh. Returning briefly to the analogy that Moten draws between the voice, mouth, and birth in his analysis of Holiday—“The grained voice engrains, the sign of the mouth, which is the birth, the sign of a kiss”—I argue that Weems’s witnessing enables us to consider the fleshiness of the voice through the lens of mothering.35

Specifically, I argue that Weems’s reprinting of these archival images is a form of taking up what Elissa Marder terms the maternal function. Differentiating the mother from the maternal function, Marder links the latter with technologies of reproduction and “the capacity for self-replication.”36 While this form of reproduction may feel obvious in the case of photography, the maternal function is also about grappling with the lost maternal body—a form of mourning that is deeply important to thinking with blackness, gender, and sexuality. Marder makes this connection through an analysis of Barthes’s Camera Lucida and grief. While photography represents the mechanized possibilities of reproduction, it also offers a way to both mourn and connect with the lost maternal body. She writes, “The photographic medium is often represented as a prosthetic maternal body that is simultaneously defined by and contrasted to the body of the biological mother. . . . To the extent that these [photographic and cinematic] technologies aim to usurp the maternal function, they are often deployed as a means of regulating or warding off anxieties that are provoked by the inevitable experience of loss that real separation from the mother invariably demands.”37 Marder’s emphasis on marking the link between photography, reproduction, and loss gives us an alternate perspective on Weems’s work as a photographer.

When we consider her enlargements a labor of reproduction and mourning, we can imagine Weems as not only disrupting circuits of sentimentality, but also producing paths of kinship born from chemical bonds. Blood is replaced with saline, which recalls the oceans that often separate diasporic communities. Calling the links between Weems and her photographic subjects kinship is important, not just because it brings attention to other emotional currents that swirl within the violent histories of displacement, but because it allows us to think gender and race in concert with agency, specifically, the agency of mothering. This agency is about creating connection, upending expectations, and scripting alternate futurities. While Weems probes difficult history, she also restores the possibility of less negative affects to her subjects by restoring their interiorities and emphasizing her connectedness—kinship—to them through a form of gendered labor.

And labor, it is. For this series, Weems selected images that spoke to her. She photographed them—because many of the images were daguerreotypes and so could not be reproduced without first being photographed. She enlarged the images and tinted them by replacing the metallic silver in the emulsion with dye, so that the photographs appear blue or red. Then, she placed a circular black mat around the images and covered them with glass inscribed with words. This is a multistep and multilayered process that required Weems to perform a great deal of care both in her thought process and in her handling of the photographs. It is this layer of care that is important in our consideration of Weems’s process. While I am not arguing that Weems makes herself into a mother or a child through her act of mechanical reproduction—especially since Moten might argue that photography itself is emblematic of the collapse between becoming-material and becoming-maternal that ungendering entails—she does enlarge her network of kinship, producing a sort of affective diaspora. She links herself to people in the photographs and invites us to think about the modes of connecting—salinity and tactility—between then and now.

One of these modes of connection is the diasporic, which Weems summons through her use of an African woman to bookend the series. By having this blue African woman flank red African American portraits, Weems connects Africa to the United States while also underscoring the multiplicity of affects at work in this diaspora. Does this blue indicate these women’s sadness at the fate of their diasporic kin? In of the bringing together of Africa and the United States we cannot help but think of slavery and separation, but we also see the activation of a particular fantasy of home, or more particularly the idea of a temporally static motherland. Though I have been calling this relationship “diasporic,” it differs from traditional notions of diaspora in that it is not about the relationship to a particular nation, but about the affective pull of the imaginary of a place. This connection is one of loss, but it is also one that speaks to optimism and the possibility of a restoration of kinship alongside violent rupture.

Figure 4.3. Carrie Mae Weems, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, installation view, Center of Contemporary Art, Seville, Spain, 2010. ©2010 Carrie Mae Weems.

In this duality, we might profitably also think about the ways in which Weems’s diaspora is enlarged through the process of selling her photographs. On the one hand, the question of copyright, brought to the fore in one way through Harvard’s threatened suit against Weems, illustrates the complex imbrications of commodification (especially in relation to photographs from the Agassiz archive) and circulation. Specifically, this tangle enables us to ask, as Yxta Murray does, whose images these are:

But whose daguerreotypes are they? Should Agassiz have ever been able to claim a right to these pictures? And, by extension, should Harvard? Agassiz pirated these images through capture and exploitation. No legitimate law should recognize this violent taking of property rights. Allowing the Agassiz daguerreotypes to remain in Harvard’s custody sustains a brutal offense, and erases instead of bears witness to the violent past. In the interests of peace, the law should transfer the property to new hands: this would involve transforming the daguerreotypes’ title from that of the University to those who bear the closest lineal relationship to the subjects of the daguerreotypes, being Drana, Renty, Jack, and Delia.38

But, thinking with this same question of property in relation to Weems’s own circulation and sale of the photographs still marks these images, or at least those manipulated in the manner that Weems does, as the property of entities who are not the enslaved. They become Weems’s intellectual property and the art collector’s or museum’s private property. On the other hand, however, following the arguments that I have laid out here, these images’ circulation, especially when understood as part of Weems’s artistic and activist oeuvre, suggests that this movement might also register as an enlargement of diaspora and kinship.

In this promiscuous fusion of kinship and diaspora, I connect Weems’s work to that of Audre Lorde, who describes an expansive version of kinship that centralizes race, geography, and maternity. Lorde theorizes kinship in her discussion of what it is to be a daughter and think affectively about history, ancestors, and migration. In an open letter to Mary Daly critiquing the white and European focus of Gyn/Ecology’s female lineages, Lorde writes, “To dismiss our black foremothers may well be to dismiss where European women learned to love.”39 This emphasis on maternity and place is deeply important for Lorde’s theorization of kinship and affective connection. We see this throughout her biomythography, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, and in Lorde’s travels.40 She traveled through West Africa—Senegal, Togo, Ghana, and Benin—for the first time in 1974 and moved to Saint Croix toward the end of her life. Her biographer, Alexis De Veaux, describes these trips as spiritual voyages: “Leaving Dahomey, and Africa, saddened her, and she wasn’t ready to go. But Lorde took from Africa what she needed: a spiritual location; the knowledge of original ancestors; a corporeal reality that was unique, timeless, and complex, and a lust to operate upon the world’s stage. When her time in Africa was over, Africa in Lorde had just begun.”41 This fusion of mother and place is inscribed not only on Zami’s pages, but on the poetry that emerged afterward in The Black Unicorn, published in 1978, which marked the beginning of Lorde’s writings on Africa, the maternal, and the sensual. In the poem “Dahomey,” for example, Lorde is explicit about the fact that her relationship with the mother is spatial:

It was in Abomey that I felt

the full blood of my fathers’ wars

and where I found my mother

Seboulisa.42

Lorde uses the occasion of visiting Abomey, the former capital city of Dahomey (now called Benin), to reference ancestral paternity and maternity, but it is notable that the paternal is marked by violence while the maternal signals a spiritual kinship. Indeed, Seboulisa, whom Lorde imagines as the Mother of us all, is a goddess to whom Lorde refers throughout her writing from this time forward. Likewise, in The Cancer Journals she compares herself to the Dahomey one-breasted women warriors and places herself in a maternal lineage of African women. These examples show us that Lorde’s invocation of Africa is not necessarily located in a search for ancestral bloodlines; rather, it is about seeking affective maternal connections. In her analysis of Lorde’s writings, Michelle Wright argues that this move to incorporate African and American heritages underscores Lorde’s deployment of “diaspora as the new collective model for Black subjectivity.”43

While this production of kinship and diaspora is premised on loss and might profitably be imagined as part of a repertoire of extended mourning, I would like to heed David Eng’s caution against linking diaspora to the “normative impulse to recuperate lost origins, to recapture the mother or motherland, and to valorize the dominant notions of social belonging and racial exclusion.”44 Instead, I would like to think of these diasporas as queer in the sense of generating new possibilities for kinship. Neither Weems nor Lorde is invested in the nation, but they are interested in feelings and the queer possibilities of these feelings. In her work on decentering nation from diaspora, Gayatri Gopinath argues that queer diaspora not only disrupts hierarchies of origin but also produces sites of novel difference: “A queer diasporic framework productively exploits the analogous relation between nation and diaspora on the one hand, and between heterosexuality and queerness on the other: in other words, queerness is to heterosexuality as the diaspora is to the nation.”45 These spaces of difference may be colored by loss, but speak to emergent eroticisms and affects underlying the formation of kinship. In Territories of the Soul, Nadia Ellis draws on José Esteban Muñoz’s discussion of utopia to conceive of diaspora as a queer horizon produced by desire, always present and always slightly out of reach. She writes, “In retaining striking traces of the gap between here and there—between the possibilities spied on the horizon and territory currently occupied—these modes produce urgent feelings of loss, desire, and zeal that mark them, like Muñoz’s utopian horizon, as queer.”46 If the creation of diaspora is born of loss, it also enables us to imagine reworking this type of excess through an alternate language of eroticism and care, which Weems and Lorde perform through their work.

Importantly, in imagining these new diasporas, we must remember that Lorde’s use of diaspora is not ungendered; it is explicitly premised on a version of matrilinearity. Like Lorde, Weems resurrects the matrilineal, though she does so in more subtle ways. Her mode of connecting with ancestors via her laborious photographic process imbues reproduction with affect and touch. Despite reinforcing Weems’ position within a network of kinship, rather than necessarily producing her as mother, I term this work “mothering.” It is not merely that the photographs are reproduced, but that Weems does so with obvious care: each photograph requires being listened to and handled. In this way, we see that this performance of photographic witnessing veers away from Moten’s critique of photography as a silencing of the mother in favor of “an imperial descent into self.”47 Instead, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried amplifies voice, thereby resurrecting the opacity of the photographic form, an opacity that Moten refers to as “the invocation of a silenced difference, a silent black materiality, in order to justify a suppression of difference in the name of (a false) universality.”48 This materiality gives the photographs life and embeds them within circuits of the erotic. This form of making possible is part of the work of mothering. As Alexis P. Gumbs argues, it is explicitly political and pedagogical: “The pedagogical work of mothering is exactly the site where a narrative will either be reproduced or interrupted. The work of Black mothering, the teaching of a set of social values that challenge a social logic which believes that we, the children of Black mothers, the queer, the deviant should not exist, is queer work.”49 For Gumbs, this politicization of mothering is queer because it speaks to a practice that has historically been denied to black women and to futures that have not yet come into being. Campt argues that this version of futurity is a type of black feminist praxis, writing that “the challenge of black feminist futurity is the constant and perpetual need to remain committed to the political necessity of what will have had to happen, because it is tethered to a different kind of ‘must.’ It is not a ‘must’ of historical certainty or Marxist teleology. It is a responsibility to create one’s own future as a practice of survival.”50 As such, this performance of witness also gives us a mode of reconsidering the work that goes on in the darkroom. The future is not yet fixed, but we can see possibility in this version of the vestibular.

This is where I return to brown jouissance and its ability to make the ambiguity of grief or joy into something else. In From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, voice and its fleshiness not only facilitate the creation of interiority, but also enable the creation of a sort of affective diaspora. Here, I ask us to think not only about the fact that Weems brings together these archival images to stand together under her name, but that she marks their connection by tinting them red or blue. Through their coloration, they have been baptized by Weems’s fleshiness to point toward a way to reckon with diaspora and the production of kinship. By reading Lorde into Weems, we see that making kin is a project necessitated by processes of racialization. Making kin stands as a rebuke against slavery’s dismantling of nuclear families and removal of agency. This is not a project to recover the individual; it is one that insists, instead, on highlighting the production of a collectivity. By making kin through her performance of witness, Weems displaces the individual with the diasporic collective and opens our imaginations toward rethinking the work of mothering: we see connection, care, mourning, and possibility.

Spirituality, Kinship, and Witnessing

Through Weems’s performance of witness we see the importance of dwelling on the fleshiness of the voice as it pertains to interiority, mothering, and diaspora, but the solicitation of voice also brings us toward the spiritual. Here, I return to Braunstein’s description of jouissance beyond the word in order to think with the particular forms of excess that are part of the voice’s ephemeral qualities. On the one hand, voice is imagined to enjoy a particular relationship to authenticity: Katherine Brewer Ball writes that “although the voice seems to flow from nowhere in particular, vaguely originating somewhere in the throat of the mouth, it is imagined to be indelibly attached to the core of the body and mind, and even to bridge the two. The voice reflects the subject at the center of the body, the inner being; it is ‘the hidden bodily treasure beyond the visible envelope.’”51 On the other hand, absent the sonic dimensions of voice, how do we describe exactly what Weems’s performance is amplifying? The spiritual, I argue, signals a particular form of fleshy excess. In thinking with spirituality, we see that it is born from materiality and yet exceeds it. I see this excess in relation to the brown jouissance mobilized by voice and witnessing in that it shows us the contours of interiority without necessarily manifesting the tangibility of a body. In Weems’s amplification of voice, she makes her interiority diffuse. We see traces of her corporeality in her care and production of kinship, yet this performance exceeds Weems. This alternate métier of excess—the space of the collective and indescribable—is what I term “the spiritual.”

In both Barthes’s and Moten’s discussion of the grain of the voice, spirituality is an important undercurrent. For Barthes, spirituality is located in the breath—that which brings together emotion and body—and its mysterious relationship to voice. He writes, “The breath is the pneuma, the soul swelling or breaking, and any exclusive art of breathing is likely to be a secretly mystical art (a mysticism leveled down to the measure of the long-playing record).”52 While he juxtaposes the breath with the corporeality of jouissance—“It is in the throat, the place where the phonic metal hardens and is segmented, in the mask that significance explodes, bringing not the soul but jouissance”—when we turn to Moten, we can see how the sonic is actually the place where spirit and matter meet.53 In describing the power of the commodity that speaks, he writes, “If the commodity could speak it would have intrinsic value, it would be infused with a certain spirit, a certain value given not from the outside, and would, therefore contradict the thesis on value—that it is not intrinsic.”54 Moten’s insistence on the resistance of the object by way of sound—not necessarily speech—allows us to read voice as spirituality, especially in relation to blackness and its history of commodification. This rereading is especially important for imagining that voice can provide resistance to the objectification that photography produces. From this perspective Weems’s project of restoring interiority reminds us of interiority’s nonphysical aspects.

This excess is part of the challenge to epistemology that brown jouissance offers. Luce Irigaray, for example, describes spiritual excess in relation to unreason and dynamics that physics or other sciences, for example, cannot account for. She writes, “What is left uninterpreted in the economy of fluids—the resistances brought to bear upon solids, for example—is in the end given over to God. Overlooking the properties of real fluids—internal frictions, pressures, movements, and so on, that is, their specific dynamics—leads to giving the real back to God, as only the idealizable characteristics of fluids are included in their mathematicization.”55 This is to say that there is always an excess of interactivity that rationality cannot account for. That she makes this argument in relation to fluidity, a space where she locates subversive dimensions of femininity, is significant in that it leads us to imagine ways in which brown jouissance’s mobilization of liquidity helps us to enact or conceive of a new politics—a new version of materiality between subject and object, a version of agency that is relational, and a way to think affect alongside the flesh. Historically, we can locate genealogies of unreason, spirituality, femininity, and alternate imaginaries of agency in the realm of the religious. Ashon Crawley, in particular, argues through a reading of the Black Pentecostal Church that performances of embodying voice—spirits who work through corporeal vessels—disrupt notions of subjectivity, agency, and reason.56 Thinking brown jouissance in relation to spirituality is not about not recognizing or fleeing violence, but about understanding its ripples as multiply layered and present in a fleshiness that is not necessarily physically tangible.

However, I also want to veer away from arguing that spirituality is the catch-all category for theorizing racialized excess.57 Instead, I am interested in how we might fuse the diasporic and the spiritual in order to deepen our conception of brown jouissance, specifically how thinking with the spiritual invites us to think about Weems’s diaspora as a form of connection that rejects certain mandates of objectivity and rationality.58

It is in the name of this diffuse form of collectivity that we also gain a way to rethink the relationship between spirituality and photography—namely, the late nineteenth-century practice of spirit photography. Nicholas Pethes situates this genre within a history of scientific experiments designed to make visible what could not be seen by the naked eye. He writes, “Accordingly, the new medium became an important part of the spiritualistic movement at the turn of the twentieth century. In its attempt to establish occult practices as empirical facts, this movement—most notably represented by the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), founded in London in 1882—applied experimental methods and technological devices to document psychic phenomena such as telepathy, telekinesis and communication with the dead.”59 While spirit photography is no longer considered part of a legacy of rational scientific practice, this impulse to make connections and kinship between the present and the past shows us a way to read Weems’s project as a subversion of photography’s attachment to projects of objectification and domination. Like spirit photography, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried brings together disparate temporalities in order to forge kinship. That it does so through voice and the performance of witnessing, technologies of the body that we might relate to “telepathy, telekinesis and communication with the dead,” is not incidental. The series speaks to a mode of thinking the fleshiness through an alternate genealogy of reason and outside of the demands of the tangibly physical.

Spirituality further gives us occasion to reexamine Weems’s tears. Tears offer a way to think about the connection between individual and communal outside of the demand for mourning. The spiritual becomes its own form of diaspora, albeit a deliberately promiscuous one. It is this queer diaspora that produces connection through an alternate understanding of how space and time become collapsed through fleshiness. For how can Weems witness what she was not alive to behold? It is not the question of relatedness, but an investment in thinking the self collectively, soliciting connection not through literal lineages of kinship, but through performances of witnessing and opacity. In performing witness, Weems listens, tethering her body to these photographic subjects in affective, amorphous, and spiritual ways.