5

Weeping Machines

Automaticity, Looping, and the Possibilities of Perversion

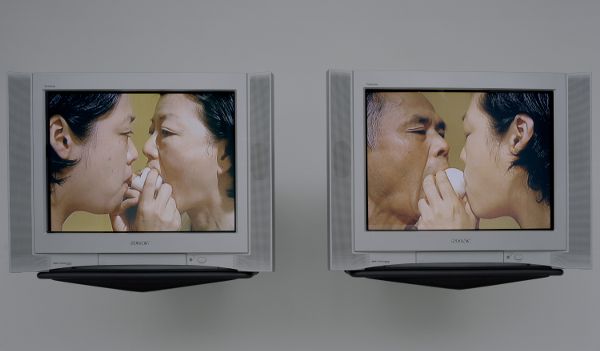

Neapolitan (2003) invites spectators to sit on a bench covered in a crocheted cozy to watch a television that plays a fourteen-minute loop of Nao Bustamante watching a projected loop of the end of the Cuban film Fresa y Chocolate (1993). Bustamante cries during the final scene, pausing only to wipe her eyes with a hanky before she rewinds to re-watch the end and cry again. Patty Chang’s In Love (2001) pairs a monitor that shows Chang and her mother locked in a passionate kiss with another monitor showing a video of her doing the same to her father while tears stream down everyone’s faces. As the film progresses, the action unspools backward; we see that what appeared to be a kiss was both of them sharing an onion. With Neapolitan and In Love, Bustamante and Chang perform women on the verge. While Bustamante and Chang cry and cry and cry, catharsis is just out of reach. Just as spectators begin to imagine resolution, the videos begin again.

Bustamante’s and Chang’s inhabitations of hysteria and perversion reveal the divergent ways that racialization positions these performances of responsiveness as excessive. This version of brown jouissance is akin to what José Esteban Muñoz calls “brown feeling,” which “chronicles a certain ethics of the self that is utilized and deployed by people of color and other minoritarian subjects who don’t feel quite right within the protocols of normative affect and comportment.”1 These brown feelings are Muñoz’s mode of describing “the ways in which minoritarian affect is always, no matter what its register, partially illegible in relation to the normative affect performed by normative citizen subjects.”2 I come to this articulation of brown jouissance by combining Muñoz’s investment in thinking with feeling as a mode of non-normativity with Dana Luciano’s argument that affective comportment be linked to sexuality. While Luciano centers her discussion on grief, she invites us to think more broadly about emotionality in relation to sexuality. Luciano writes that grief “constitutes a crucial dimension of the dispositif of sexuality itself: the modern intensification of the body, its energies, and its meanings.”3 Hence, I argue that we can understand Bustamante’s and Chang’s performances of emotion as part of a constellation of sexuality because they are legible through norms of labor, intimacy, and brown femininity.

Bustamante’s crying can be indexed to stereotypes of the overly sensitive, hysterical Latina, while Chang’s crying can be attached to the specter of the insensate assimilated Asian American. Through their occupation of opposite sides of the spectrum of “appropriate” emotionality, Bustamante’s and Chang’s performances of crying illuminate the complexity of brown feminine performances of emotion. These performances oscillate between grief, happiness, relief, and pain and resist any fixed reading. That is what makes them arresting works of art to think with, but in their divergence each also highlights the contours of what constitutes normative comportment and the underlying assumption that black and brown people do not feel, they merely react. This is a legacy of the linkage of interiority to whiteness that Denise Ferreira da Silva describes in Toward a Global Idea of Race when she differentiates between the subject and Other. As I wrote in the introduction, the subject occupies “the stage of interiority, where universal reason plays its sovereign role as universal poesis,” while the Other is assigned to the realm of the external as an “affectable I.”4 This notion of affectability, reactivity, and responsiveness is what I connect with automaticity.

Automaticity, which occupies the register of the un-thought and robotic, issues a challenge to the norms of affective comportment because it suggests sensation without—or at least out of joint with—feeling. I argue that this notion of automatic responsiveness can be found in several post-Enlightenment discourses. We can trace this genealogy through a history of automata, which in the late eighteenth century became invested in replicating internal processes—witness the popular defecating duck whose appearance Jessica Riskin attributes to designers wanting “not only to mimic the outward manifestations of life, but also to follow as closely as possible the mechanisms that produced these manifestations.”5 We can also locate automaticity in theorizations of the body as mechanical, which led to a cleavage between authenticity and acting. Joseph Roach, in an explanation of Denis Diderot’s philosophy of acting, describes it as approximation, because the body is “a virtually soulless machine possessing vital drives but no will.”6 Roach further describes Diderot’s perception of the eighteenth-century actor as “imitating the exterior signs of emotion so perfectly that you can’t tell the difference; his cries of anguish are marked in his memory, his gestures of despair have been prepared in advance; he knows the precise cue to start his tears flowing.”7 Automaticity, then, renders corporeality and emotionality suspect, positioning them in relation to theatricality and insincerity and against ideologies of authenticity.

Bustamante and Chang, I argue, play with this idea of automaticity, highlighting the ways that it undergirds how minoritarian performances register, but also using it to subvert these norms through their performances of excessive theatricality. These performances challenge the norms of intimacy between performer and spectator and activate multiple frameworks of opacity in their confounding of transparency, domesticity, and temporality.

Emotional Excess, Vibrators, and Melodrama

While we do not see what makes Bustamante cry, we bear witness to her rapt attention. Light from the television flickers across her face as the music swells and tears stream down her face. Her shoulders heave, her mouth emits a few low sobs, and her nose runs. The scene ends, and Bustamante reaches for the remote control to rewind the clip. We hear the same music and see Bustamante cry again. She takes a sip of water; she uses the remote to rewind. In this performance of automatized sensation and emotional looping, Bustamante plays with what it is to perform the excessively emotional Latina. By suturing this mode of theatricality to the loop, however, Bustamante resists the overdetermination of this stereotype in favor of illuminating the orgasmic and masturbatory pleasures of the brown hysterical body and its domestic excesses.

Bustamante’s inhabitation of the emotional Latina has had particular resonance with critics. Lindsey Westbrook, reviewing the piece in Artweek, frames Neapolitan as a performance of Chicana mourning. She writes:

Figure 5.1. Nao Bustamante, still from Neapolitan. ©2003 Nao Bustamante.

Nao Bustamante’s Neopolitan is also brand new and deals with several themes that recur in her work; emotionality, vulnerability and stereotypes of gender and Mexican-American culture; we watch her watching a scene from the Cuban film Strawberries and Chocolate. She is making herself cry, periodically rewinding the tape and wiping her eyes on a Mexican flag hanky. The work is profoundly self-conscious, of course, and, for that reason, cynical. But it is also genuinely sad, expressing sorrow and mourning, perhaps, for the current world situation.8

Proposing that the hanky is merely a colored dish towel, Muñoz argues that Westbrook’s review highlights the “various ways in which brown paranoia is not something that can be wished away, no matter how much we would like to fully escape the regime of paranoia,” while also calling attention to the subversive possibilities of Bustamante’s performance—namely, that by reading her Mexican American identity alongside her crying, depression and the depressive position become strategies of minoritarian critique and signal the possibility inherent in opacity.9 What is important about the difference between Westbrook’s and Muñoz’s interpretations of Bustamante’s performance is the status accorded to her crying. For Westbrook, Bustamante’s crying is decipherable as part of Bustamante’s sorrow at being a minoritarian subject; hers are the tears of overdetermination, intertwined with the wound of representation and its relationship to violent geopolitical histories. Westbrook reads Bustamante as participating in a ritual of mourning. Muñoz, however, understands Bustamante’s tears as a strategic form of self-determination in which she navigates these colonial histories, but also plays with them and with the expectations that they produce. Muñoz reads her performance within his theorization of “feeling brown” and positions her tears as a representational strategy that acknowledges minoritarian subjects’ estrangement from affective norms, but rewrites this non-normativity as a mode of performing optimism that simultaneously recognizes historical trauma.

Bracketing the question of whether or not Neapolitan fits within the genre of mourning, I focus on the piece as a performance that plays with racialized concepts of automaticity. By this I mean that Bustamante’s excessive crying signals a history of perceiving brown female responsiveness, particularly Latina emotionality, as automatic—less thoughtful and more reactive—and that Bustamante’s own framing of her performance plays with the repetitive pleasures of this automaticity.

Indeed, Bustamante’s performance of excessive emotion can be positioned within a history that links black and brown people and white women to sensation rather than sensibility. In elaborating on this dichotomy further, Kyla Schuller argues that women were characterized as impressible, which is to say that their bodies and minds were overly responsive to their external environments. For Schuller,

Impressibility of character describes emotional excitability above and beyond its stimulating impression. Anglo-Saxons, at the top of the evolutionary ladder, possessed the most highly differentiated physical, mental, and psychological profiles, such that woman’s “form” is more unlike that of men. The bodies and minds of civilized women, on account of their being more childlike than men’s, retained more plasticity; correspondingly, their hyperimpressibility triggered responses exceeding the stimulating impression.10

These taxonomies not only positioned “excessive” emotional response outside the realm of the civilized, but by the same logic also registered the emotional responses of women, and brown and black people as excessive and non-normative.

Muñoz himself has written much on the non-normativity of Latinx affect. While he frames the stereotype of the “hot ’n’ spicy spic” against the idea of whiteness as lack, excess is still a key term in his discussion: “The ‘failure’ of Latino affect, in relation to the hegemonic protocols of North American affective comportment, revolves around an understanding of the Latina or the Latino as affective excess. . . . Thus the ‘hot ’n’ spicy spic’ is a subject who cannot be contained within the sparse affective landscape of Anglo North America. This then accounts for the ways in which Latina/o citizen-subjects find their way through subgroups that perform the self in affectively extravagant fashions.”11 Similarly, writing in a psychoanalytic vein, Antonio Viego describes the untranslatability of traditional Latino maladies such as “los nervios” and “attaques.”12

Further, within this space of the emotionally excessive, sensation becomes linked to a temporality of the present, which further demarcates it as uncouth. In contrast to sentiment, which is what civilized men possess as an internalized psychic structure that requires a narrative temporality of past, present, and future, sensation is a corporeal response that exists only in the now. Luciano writes, “‘Sensation’ signals a mode of intensified embodiment in which all times but the present fall away—a condition simultaneously desired, in its recollection of the infantile state, and feared, in its negation of social agency.”13 Those who experience only sensation exist in the present; they do not exhibit agency since the narrative structure of time is foreclosed to them.14 This fetishization of the moment and the imagined corporeal excess of these sensational bodies mark them as out of sync with normative society. Through her use of the loop, Bustamante plays with what it is to inhabit the present. She is always crying, automatically performing responsiveness, and always out of joint.

Interestingly, in her artist statement, Bustamante embeds her understanding of this performance within the realm of mechanized sexuality, which nuances our understanding of the way she frames excessiveness and automaticity. She refers to the final scene of Fresa y Chocolate as “an emotional vibrator of sorts.”15 The film, directed by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Juan Carlos Tabío tells the story of what becomes a friendship between a university student, David, and a gay artist, Diego, in Cuba in 1979. It is a story about the seductive nature of ideas, the power of art, and exile. At the end of the film, Diego leaves Cuba to avoid persecution, and the men embrace. Bustamante describes the appeal of this scene thus: “In this scene the two main characters hug, that’s it, they hug, a plump moment of relief and connection for the emotional body. The music swells and so do my eyes. I cry every time, inducing a momentary emotional response by technical manipulation of my psyche.”16 If the film functions as a technology to elicit response, then what viewers watch is Bustamante’s excessive responsiveness. The barrage of tears enters the realm of the sexual not only because the installation produces a type of voyeurism (we watch Bustamante watch), but also because Bustamante understands her response within the frame of sexuality.

In Bustamante’s invocation of the vibrator, two different ideas about mechanical sex become simultaneously operationalized. On the one hand, we are allowed to think about our current era as one in which all sex is mediated in the way that Luciana Parisi suggests: “In the age of cybernetics, sex is no longer a private act practiced between the walls of the bedroom. In particular, human sex no longer seems to involve the set of social and cultural codes that used to characterize sexual identity and reproductive coupling.”17 Her comments speak to the way in which interactions with machines have restructured sexuality, sexual relations, and identity. Parisi focuses on this invasion of technology through the notion of “mediated sex.” In this view machines (nonhuman ones especially) are tools that enable humans to have sex with each other in numerous different ways. We certainly see this at work in Bustamante’s suggestion that the end of the film is a technology that facilitates her emotional climax. On the other hand, the vibrator also raises the specter of sexual response as itself mechanical. This idea is behind the attention to anatomy and physiology that William Masters and Virginia Johnson ushered into modern sexual thought by using Ulysses, their technologically enhanced dildo, to help map out female sexual response for their ground-breaking 1966 book, Human Sexual Response. Masters and Johnson’s carefully measured results were based on the interventions of film and photography. Couples were filmed during intercourse, women were filmed masturbating, both manually and with Ulysses, which took intravaginal photographs at rapid intervals during orgasm. The use of these technologies speaks both to the interconnectedness of cinema and science and to the desire for precision that automation was perceived to provide. Unlike the women used in the study, Ulysses was not subject to subjective interpretations of truth. Although the women’s comments were used to ascertain whether orgasm had taken place, they became part of a knowledge loop that ricocheted between their statements and the physiological data gleamed in the laboratory. In this instance it is Ulysses’ approximation of humanity that is valued; partial physical similitude was coupled with the mechanical absence of feeling. Ulysses’ ability to record but not interpret and to penetrate but not feel were prized above all else, in a way that is emblematic of what Peter Galison calls a machine ideal—“the machine as a neutral and transparent operator that would serve both as an instrument of registration without intervention and as an ideal for the moral discipline of the scientists themselves.”18 Although Masters and Johnson acknowledged the potential for different responses with Ulysses and with a partner, they used data from their research to argue for their sameness, a rhetorical strategy that reopens the question of Ulysses’ subjectivity. In defending the use of Ulysses as an appropriate sex object, they wrote: “In view of the artificial nature of the equipment, legitimate issue may be raised with the integrity of observed reaction patterns. Suffice it to say that intravaginal physiologic response corresponds in every way with previously established reaction patterns observed and recorded during hundreds of cycles in response to automanipulation.”19 In this statement Ulysses is assumed to produce the same physiological effects as masturbation, which, in turn, is already assumed to produce the same effects as intercourse. Through this argument for the data’s simultaneous difference and sameness, we see the dilemma of simulation. In this case, using the machine to simulate sex opens the category of sex. If copulation with a machine provides the same result as human intercourse, what is the difference between the two? Transposing these insights to the installation unearths the ways that Bustamante exploits her body’s learned response to a particular stimulus, displaying her body’s automaticity.

The automaticity of the vibrator also suggests an alternate dimension to thinking about the loop—a mechanical temporality that produces the same results over and over again. Lauren Berlant argues that the loop (which Bustamante watches and which we watch), allows us to see the forms of agency and ambiguity that Bustamante is playing with. Berlant writes, “She is reveling in the kind of self-imitation that constitutes pleasure, whether or not it feels good.”20 Berlant situates this ambiguous affective performance within Muñoz’s description of the oscillation between subject and object, which minoritarian subjects perform. For Berlant the loop not only signals the porosity of subject and object, but also highlights the minoritarian subject’s particular interaction with forms of historicity—by being both “caught” in modes of projection and able to manipulate that form of stasis. Berlant writes that the loop “enacts a desire to be in a temporality that is impossible to destroy as long as the technology can hold the world up—here, a world of longing and displacement from so many objects, enduring as long as there is memory, electricity, broadcast satellites, and batteries in the remote. It matters that the thing that brings Bustamante’s video object to her is called a remote, even though she holds it: that is the remote’s magic, to deny its own name. It’s a limited magic.”21 Technology, then, is vital in creating Bustamante’s agency (and our voyeuristic pleasure). It highlights both Bustamante’s relationship to automaticity and the pleasure of this mode of embodiment. Additionally, by insisting on a repetition of the present, Bustamante moves toward a jouissance of existing in the now. Brown jouissance is part of this insistence on feeling with the moment against the demand to present feeling in accordance with the norms of chronology.

Further, in Bustamante’s description of the film’s final scene as a “vibrator of sorts,” we see that she is equating the film’s moments of catharsis with sexual release. In this way, she harkens back to the vibrator’s late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century function as providing relief for hysterical women through orgasm.22 Within the context of hysteria, orgasm, as induced by the vibrator, was posited as the solution to the larger structural problems of femininity. Generally imagined as a pathology related to “overcivilization,” hysteria became a technology of race-making that furthered racial divisions between women, positioning white women within the category of the frigid and black and brown women in that of the hyperfecund and hypersexual.23 Laura Briggs writes, “It is in this arena that the racial discourse of nervousness emerged in a very familiar form, one that had already been (and would continue to be) reiterated often in Euro-American culture: ‘overcivilized’ women avoided sex and were unwilling or incapable of bearing many (or any) children, ‘savage’ women gave birth easily and often and were hypersexual.”24 Briggs argues that these dual discourses underline the ways that white women’s “struggle for social and political autonomy from white men” was framed not only as a threat to masculinity, but as a racial threat.25 In this way we can see Bustamante’s inhabitation of the hysterical woman not only as about indexing the overly emotional Latina, but as about posing a direct threat to whiteness through hypersexuality as signaled by the vibrator and Bustamante’s linkage of automaticity to pleasure.

Additionally, Bustamante nuances this hypersexuality by attaching it to the domestic. Whereas scholars have argued that hysteria emerged as a form of embodied protest against the confines of domesticity in the late nineteenth century, Bustamante invites us to explore her sensational excess within the domestic space of the coz(s)y, which provides the setting for these repeated scenes of crying.26 Doyle writes, “The installation is full of pleasure and care; we see this in the artist’s obvious affection for the film and the loving hand applied to the installation itself, in which the television becomes a homey shrine.”27 She describes Bustamante’s installation in detail:

The monitor is shrouded in domestic ornaments and grandmotherly doilies—not genteel white lace but a riot of garish orange and yellow. The monitor is cloaked in crocheted yarn; little tassels adorn every corner and dot the blanket that wraps around the monitor’s base. The headphone’s earpieces and wires have cute coverings, turning them into adorable caps. The bench is covered in its own tailored outfit. A black crow perches atop this mountain, wearing a crocheted hat. The installation is customized for each appearance. Electric cords, outlets, and power strips all wear yarn cozies that take the artist several days of continuous labor to fashion.28

While the coziness of the installation brings Bustamante’s pleasure within the framework of melodrama and the feminine pleasure of sentimentality, it also hints at a deeper menace: that of the mundane comingling of pleasure and the violence of racialization.

The cosies and their excessiveness—both in color and number—recall what Muñoz has called Latino camp and names as a minoritarian strategy of survival.29 That Bustamante has so obviously labored to create them is a statement about her relationship to this aesthetic, the feminine space of the home, and the forms of labor that go into crafting. Jeanne Vaccaro argues that craft “evokes the remunerative, utilitarian, ornamental, and manual labor and laborers—the feminine, ethnic and ‘primitive.’ A philosophy that subordinates labor, the manual, and the sense of touch to abstraction, rationality, and the sense of sight operates in a political economy of devaluing bodies.”30 Further, Lacey Jane Roberts suggests that crafting itself is queer because of its relationship to the anachronistic and the slipperiness of its designation as something professional or amateurish: “Institutions, practitioners, curators, and critics have often claimed the word craft cannot be defined, and this ambiguity is largely viewed as a negative quality. While craft represents a large scope of labor practices, methods, skills, mediums, and makers, it typically is embedded with a tinge of nonnormativity and otherness.”31 For Julia Wilson Bryan it is these very qualities that allow craft to highlight alternate forms of relating to materiality and knowledge production: “Craft draws its very strength from its anachronistic quality and its ties to traditions, both its adherence to conventional artisanal labor and also its more messy reinventions. Handmaking maintains its integrity in response to and in opposition to industrialization. . . . Craft embodies its histories in its materials.”32 What Wilson Bryan draws our attention to is the very particular micro-historical relations embedded in Bustamante’s installation—Who taught her to craft and how? Why these colors?—which produce meaning, though much of it is opaque to the viewer. Through the materiality of craft, however, we also see that the handmade, which Vaccaro describes in relation to “the politics of the hand, that which is worked on, and the sensory feelings and textures of crafting,” is central to thinking about the form of agency that Bustamante is putting on display.33

Figure 5.2. Nao Bustamante, Neapolitan, installation view, at the Broad, Los Angeles, CA, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Through crafting, we see an appeal to an excessiveness that is not codified by the relentless racializing gaze. Instead, we see an alternate aesthetics of tactility and softness, the labor of the marginalized, and a domesticity that stitches together pleasure and difficulty through technology—or manipulations of the hand. Through the cosy, Neapolitan’s teary spectacle gives way to the possibility of pleasure, subversion, and a shifted sensoria. The space of racialized excessiveness may not be pleasurable, but Bustamante offers ways to think around that by inviting you into her space and overwhelming you with tactility.

It is through her hailing of the domestic that Bustamante generates a scene of intimacy. Yet this intimacy is not about transparency, but about genre and the opacity that it offers. I come to this argument by thinking through Bustamante’s mobilization of melodrama, a term that both Muñoz and Doyle use to describe Bustamante’s mode of watching Fresa y Chocolate. In Bustamante’s performance of automatic crying, she draws attention to the ambiguous nature of crying in that her tears fall without necessarily being coded as mourning or sadness, but instead of attaching particular meaning to Bustamante’s response, I take Muñoz’s and Doyle’s disparate analyses of the last scene of the film as further evidence of Bustamante’s performance of opacity.

For Muñoz, the film is about “the way in which queerness can finally not be held by the nation-state. . . . Queerness is the site of emotional breakdown and the activation of the melodrama in the installation. . . . I would thus position Bustamante’s art object as a corrective in relation to the homophobic developmental plot. Queerness, the installation shows, never fully disappears; instead it haunts the present.”34 This analysis sutures the domestic with the nation-state and reads Bustamante’s crying as part of the film’s queer excess. In the film, queer excess and exile from the nation-state is literalized in Diego, whose departure from Cuba precipitates the hug from David, who has spent much of the film learning to respect Diego, Diego’s homosexuality, and his critiques of the government. José Quiroga reads the film as working to soften the perception of the government as anti-homosexual while expelling the concept of a gay identity from national consciousness in order to prioritize Cuban nationalism.35 Bustamante’s crying, however, prevents queerness from actually being removed from the nation-state. For Muñoz, Bustamante’s melodramatic response is part of a larger statement about the ways affect can revive queer possibilities in its oscillation between the scale of the nation and the domestic. We might also profitably think with Elizabeth Anker’s discussion of melodrama as a form of national rhetoric in Orgies of Feeling. While Anker discusses melodrama within the context of the United States in order to produce national heroes and villains, we might think about what it means for Bustamante, who is Mexican American, to watch a Cuban film in which Cuba stages its own drama in which those who stay are heroic and accepting of difference while queers are exiled.36 Does the drama of exile mirror her own familial histories of migration across borders? Is there something about the relationship between Mexico and Cuba, which was uniquely friendly until 1998, that facilitates this connection? Do these shared national residues form part of the film’s ability to function as an emotional vibrator?

In her reading of Bustamante’s relationship to Fresa y Chocolate, however, Doyle, is more invested in situating Bustamante’s viewing within a history of feminine viewing habits. She emphasizes the pleasures of the domestic. She writes, “At the heart of Neapolitan is a scene of indulgence, the treat of a weepie”37—a genre that “offers a fantasy escape for the identifying women in the audience,” according to Laura Mulvey: “The illusion is so strongly marked by recognizable, real and familiar traps that escape is closer to a day dream than to a fairy story.”38 Thus, Doyle’s hailing of Bustamante’s viewing pleasure as akin to that of watching “a weepie” places us solidly in the realm of feminized domesticity and fantasy. This is the space that for Doyle is marked by indulgence and that we can read as masturbatory owing to its relationship with both the vibrator and fantasy. Ien Ang connects melodrama with a resistance to the banality of everyday life. Instead of revealing its artifice, melodrama infuses the daily with excessive emotion. Ang writes: “The melodramatic imagination is therefore the expression of a refusal, or inability, to accept insignificant everyday life as banal and meaningless, and is born of a vague, inarticulate dissatisfaction with existence here and now.”39 While melodrama offers the balm of emotionality, it also threatens to evacuate specificity in favor of responsiveness and repetition. Here, Tania Modleski points out the importance of melodrama’s temporality of non-progress, which enables this feeling of indulgence and escape. She writes, “Unlike most Hollywood narratives, which give the impression of a progressive movement toward an end that is significantly different from the beginning, much melodrama gives the impression of a ceaseless returning to a prior state.”40 The language of melodrama, then, vacates the content of interiority by focusing on swirls of feeling rather than their particular province. Melodrama introduces the idea of inhabiting an affective reality in which progress is not the goal, but a masturbatory excess of tears is.

Endurance, Assimilation, and Perversion

At the onset, Patty Chang’s installation provokes spectators’ discomfort because it appears as though we are watching something deeply perverse—an adult child passionately kissing her parents, in front of a camera no less. In this performance of excessive parental affection, we see a different register of automaticity—one that brings endurance, perversity, and the specter of being insensate to the fore. The flagrant nature of this perversity announces itself as a failure of assimilation and brings our attention to the residue of racialization. As a discourse, assimilation is, of course, deeply fraught. Bracketing the question of who is allowed to participate and what it means to posit whiteness as normal, I read this installation as a critique of assimilation. Although assimilation is just one road toward what Jeffrey Alexander describes as the incorporation of difference, the theory behind assimilation relies on the idea that difference can be erased for certain groups while also imagining that some residue remains. Alexander writes, “Assimilation is possible to the degree that socialization channels exist that can provide ‘civilizing’ or ‘purifying’ processes—through interaction, education, or mass mediated representation—that allow persons to be separated from their primordial qualities. It is not the qualities themselves that are purified or accepted but the persons who formerly, and often still privately, bear them.”41 In Alexander’s mention of the importance of pedagogy for thinking assimilation, we move toward theorizing the loss that accompanies it, which David Eng and Anne Anlin Cheng have written about as a form of racialized melancholy as well as an unstated understanding of the assimilative body as passive slate for inscription—which, in turn, speaks further toward Muñoz’s assessment of whiteness as lack.42

Figure 5.3. Patty Chang, In Love, 2001. Two-channel video installation, 3 min., 28 sec.; dimensions variable. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Purchased with funds provided by Janet Karatz Dreisen, 2002.

In lieu of melancholy, however, Chang foregrounds the possibility of perversion. This sensual potentiality gives voice to the assumption that assimilation cannot tame what Celine Parreñas Shimizu describes as “perverse interiority,” though the actual nuances of this perversity remain unknowable.43 Further, by revealing what one might imagine to be tears of shame to be onion-induced, Chang suggests that she (and her parents) might be shameless, thereby refusing normative affective codes of behavior that one might thrust upon the situation and activating the idea of automaticity (solicited by the onion instead of emotion). We might consider this invocation of shamelessness part of Chang’s engagement with the trope of Asian and Asian American female hypersexuality, whose legacy Parreñas Shimizu describes as “a vibrant combination of fantasy and reality charging the fashioning of the self that moralism, or the power of puritanical discourse, and scopophilia, or the love of looking, cannot accommodate.”44 The embrace of this excess is political in that it acts as a “productive perversity” which challenges “the power of normalcy, especially in limiting definitions of sexuality,” while also enabling a way “to make sense of one’s punishment and disciplining as Asian American women hypersexualized in representation.”45

This perverse excess, however, is also part of an economy that understands Asian and Asian American femininity through the lens of passivity. Parreñas Shimizu works through this dichotomy in her analysis of Annabel Chong, the Singaporean porn star who became famous for starring in The World’s Biggest Gangbang in which she had penetrative sex with 251 men in one session. Parreñas Shimizu reads Chong’s performance of bottoming and her persona as a model minority, which she establishes by discussing her life as a student and subsequent career in IT, as two elements that play into the ideology of Asian passivity. The form of passivity embodied in the idea of the model minority is what offers the possibility of assimilation and is part of the mobilization of the mundane, which Ju Yon Kim uses to describe particular Asian and Asian American performances of racialization. Kim writes, “The mundane, as something enacted by the body that is not necessarily of the body, inserts a productive uncertainty whereby the prerogative to manage racial others can be channeled into efforts to change their behaviors. Yet the presumed incompleteness of these endeavors, exemplified by Homi Bhabha’s ‘almost the same, but not quite’ colonial subject, affirms the very boundaries that such efforts are meant to erase.”46 Kim traces this tension between viewing Asian and Asian Americans as possessing difference that is easily (almost) erased through habit in her discussion of Chinese laborers, Japanese war brides, Korean shopkeepers in the wake of the LA riots of the 1990s, and the myth of the model minority. She writes, “Associated variously with an American work ethic, Confucian values, or an inhuman mechanical efficacy, the same model minority traits lauded for exemplifying American self-sufficiency can just as easily signify an un-American lack of playfulness, and even forebode the ascendance of Asia.”47 Here, we see the double valence of passivity in the model minority as passivity comes to signify the tendency toward uncritical labor and the threat of automaticity as part of the baggage of racialization. This is a different idea of automaticity than that which Bustamante plays with; it is an idea of automaticity that is connected to histories of capitalism and globalization. It is an automaticity that is not about an excessive emotional response to a stimulus, but automaticity as symptomatic of an inability (or lack of desire) to maintain a self in the face of prevailing structures. Its underside is endurance.

Eric Hayot connects this idea of automaticity with mechanization and the impulses of capitalism to extract as much labor from subjects as possible. In his analysis of the coolie stereotype, he writes:

The coolie’s ability to endure small levels of pain or consume only the most meager food and lodging represented an almost inhuman adaptation to contemporary forms of modern labor. . . . An “absence of nerves,” remarkable “staying qualities,” and a “capacity to wait without complaint and to bear with calm endurance” were all features of Chinese people in general described by Arthur Smith in his 1894 Chinese Characteristics, the most widely read American work on China in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries . . . The coolie’s biologically impossible body was displaced ground for an awareness of the transformation of the laboring body into machine.48

Rachel Lee argues that Hayot’s analysis “underscores the ‘impossible biology’ of the coolie’s body—and its alignments with both ‘past and future, animal and superhuman’ capacities—as well as the ‘possible end to suffering via indifference’ palpable in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.”49 For Lee, this relationship between mechanization and endurance works to produce Asian American bodies as fragmented—both in the sense that capitalism demands fragmentation for efficiency and in the sense of being seen as superhuman (requiring less nutrition, for example, than others), on the one hand, and animalistic (lacking in nerves), on the other.

By using the onion to solicit tears, Chang alludes to her body’s position within this racialized economy of automaticity, but she challenges the charge of passivity both through her active engagement with her parents and through her mobilization of the perversity of endurance. While Hayot and Lee both point to the suggestion that Asian American bodies are seen as able to endure, performances of endurance are usually considered the province of white masculinity in that they indicate an ability to use suffering to bolster one’s sense of self. Kent Brintnall argues that tableaux of masculine suffering (such as presented by Mel Gibson, Francis Bacon, and Robert Mapplethorpe) highlight the reification of privilege that can occur in the face of pain. Brintnall writes, “Although suffering can signify vulnerability, weakness and limitation, enduring pain and injury requires resilience. Similarly, while display of the male body can both render it an object of erotic contemplation and reveal the fabrication of the masculine ideal, it can also mark the body as ideal, worthy of attention and admiration. This allure can, at the same time, make the masochistic trial itself appealing.”50 Brintnall evokes masochism as a way for us to understand how performances of masculinity rely on a narrative of triumph over woundedness. His suturing of eroticism and racialization is instructive for my analysis of Chang’s performance, however, because it points to the ways that her performance of endurance adheres to altogether different conventions. Not only is the scene of suffering quieter than those that position the male body as imperiled—we see Chang and her parents only from the shoulders up, which suggests that it is not her body, but her mind that is imperiled—but the specter of masochism does not resolve itself into a privileged position. Instead, it furthers the spectacle of Chang’s racial difference. By this I mean that it invokes the specter of Asian female masochism that haunts Annabel Chong’s performance in The World’s Biggest Gangbang. If we read Chang and her parents’ performance as part of an economy of masochism rather than endurance, we see that both automaticity and this sexual excess are part of the coding of brown femininity as flesh.

Chang’s mobilization of tears, however, undercuts this relationship between racial excess and automaticity when we focus on the role of the onion. Chang describes In Love as a direct citation of Marina Abramovic’s 1995 piece The Onion, in which Abramovic eats an onion in its entirety while her voice records a list of banal annoyances. This is a performance of endurance that calls attention to the trials of femininity. Doyle describes it thus:

The act of eating the onion begins as a perversely masochistic variant of using an onion to shed artificial tears—an external provocation to cry over a life not interesting enough to cry about. As the loop of complaints repeats itself, we watch her struggle over her own instinct as she takes one large bite from the onion after another. We hear her moan and whimper as she chokes it back, skin and all. (This aspect of the performance is almost erotic.) Over time she disintegrates before our eyes: her composed face collapses in abjection and grief.51

Doyle sees this piece as resonating with viewers’ disgust because they find themselves empathetically tasting the onion’s bitterness as they watch Abramovic eat. The viewer, then, moves from questioning whether Abramovic’s tears are authentic toward pondering their deeper meaning. Doyle narrates, “In the end, it is not the authenticity of her tears that you question but their artificiality, in part because as you watch this video it is hard not to have a physical reaction in sympathy with the manifest difficulty of eating a raw onion while suppressing the impulse to gag. . . . Here what starts as a theatrical production of artificial tears appears to morph into real tears over the artificiality of the performance of her daily life.”52 Feeling zings through the circuits of sympathy, viewers cannot help but project onto Abramovic and her alimentary-induced suffering. By contrast, we might read Chang’s use of the onion as a theatrical trick, since it elicits tears without feeling and thereby highlights the difference between the “realness” of Abramovic’s performance and the lack of authenticity in Chang’s. Further, the reverse temporality of Chang’s piece blocks spectatorial projections of empathy because viewers do not understand that an onion is being eaten until the end. Instead viewers meet the (artificial, real?) threat of incest and its relationship to the specter of racialized perversity head-on. This temporal confusion solicits corporeal identification and empathy in very different ways. In an interview with Eve Oishi, Chang says that she was drawn to Abramovic’s piece, but felt sad in response to watching the video: “I felt it was sad to be having this experience alone. Sharing an awful experience with another person binds you together. . . . As I thought about this awful yet exquisitely touching act, I imagined . . . the least likely people I would want to do it with . . . my parents. And this is why I attempted to make In Love.”53 In this way, the focus is less on the act of eating than thinking the onion as an object that connects Chang to her parents. Through the onion, all three of them veer close to incest, enduring its proximity as well as its noxious fumes. By using an onion to triangulate her relationship to her parents, Chang suggests that kinship is a matter of food, endurance, eroticism, and love.

In Love becomes a piece about her relationship with her parents, returning us to the specter of incest and allowing us to position Chang’s piece alongside the plethora of incest memoirs that emerged in the United States and Canada in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Gillian Harkins reads incest memoirs as a genre unto themselves—“a dominant trope for a national culture in crisis, without its moorings in cold war security rubrics or the rationalities of welfare statism.”54 Incest narratives, Harkins argues, garnered much of their force from the refashioning of the family under neoliberalism, making it “into the synecdoche for all broader social relations,” and asserting that “family values were cultural, not economic or political per se.”55 These memoirs elaborated the production of modern neoliberal subjects by focusing on self-reliance, confession, and self-narration. While earlier fictionalized narratives of incest from the 1970s, such as I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, The Color Purple, Corregidora, and The Bluest Eye, all authored by African American women, explored incest as a way to “interrogate the use of race and racial hierarchies to devalue black female children in ways that subject them to increased sexual vulnerability,” the spectacularization of incest reread these critiques as examples of African American familial pathology.56 The difference between these two visions of the incest narrative is powerful. On the one hand, we get a critique of national structures of care, and on the other, we see an articulation of autonomy and privatization. It is telling, I think, that this shift also occurs through a generic transformation—we move from narrative (and occasionally autobiographical fiction) to memoir.

In Love falls between these two modes of narrativizing incest. On the one hand, it plays with the idea of confession, thereby summoning the agency and resistance of that discourse—though it fails to coopt confession’s production of interiority, preferring, instead, to display the opacity of perversion. On the other hand, it also activates the specter of incest as a way to highlight the assumptions that surround Asian Americans even as it works to undermine those ideas by revealing the assumption of incest to be a cinematic trick. However, I also want to suggest that by showing the videos in reverse temporality, Chang plays with the past/future temporal orientation of automaticity. Most saliently, however, In Love differs from these models of incest narratives in that Chang cannot be isolated as the sole protagonist. She is always pictured in relation to her mother or father. In this way, I argue, Chang highlights the willingness of parents to endure—perhaps this is a different form of love than the primarily sexualized love of incest. This is about the parental bond and its fleshiness, which comes to the fore through Chang’s manipulation of tears to illuminate facets of racialized excess. Importantly, the piece is also about eating. As its description on the Guggenheim Museum’s website suggests, “Chang examines the territory of the primal, parental connection in her work In Love (2001). . . . [Parents and child] bite into it slowly, pausing as they take turns offering it to each other, as if it suggests the proverbial, forbidden fruit. Parents and child swallow before they take additional bites, blinking hard to hold back tears from the onion’s sharpness and pungency.”57 Not only are these family members tolerating the onion, they chew it, swallow it, and exchange its morsels so as to nourish the other. Here, we might think about the relationship between eating as part of the realm of the mundane and the imagined controls enacted to police Chinese American people through diet. This is part of the legacy that Chang, born in the Bay Area, recollects through this performative eating. Kim writes:

Dietary preferences were not simply a matter of taste, but intrinsic to the American worker’s “character,” and essential to fulfilling the responsibilities of a republican government. Offering its own theory of consubstantiation, the state senate located the body politic in the very meat and bread consumed by the nation’s citizens. The presumed irreconcilability of “meat” and “rice” as metonyms for American and Chinese ways of living set distinct racial limits on the struggle for workers’ rights by suggesting that the very “stuff” of Chinese and American labor differed.58

By reading Chang through this history, I want to suggest that In Love also shows the generational pain of assimilation: after all, the white onion they share is sharper and harsher than scallions or green onions more traditionally associated with Chinese food. In this reading, the reverse temporality of the piece is also significant in that it prevents us from reading this as a static triumphant narrative of assimilation, the onion is reconstituted in the end. The mastication that we watch unfold in slow sensual time does not dissipate difficulty even as it might call upon the bonds of kinship—diasporic and otherwise.

The veneer of foreignness, which haunts Chang’s installation in its manipulation of perversity and through its critique of discourses of assimilation, is part of what Karen Shimikawa labels “abjection.” Through her analysis of Asian American performance, Shimikawa argues that Asian Americans are perpetually positioned as external to Americanness through the suturing of nation, race, ethnicity, and bodily identity. Shimikawa writes, “Read as abject, Asian Americanness thus occupies a role both necessary to and mutually constitutive of national subject formation— but it does not result in the formation of an Asian American subject or even an Asian American object.”59 By drawing on Shimikawa’s discussion of Asian American identity as occupying the space outside of subject and object, we can situate Chang’s performance within the parameters of brown jouissance. Like Bustamante, Chang manipulates our sense of time—here, playing with the idea of Asian Americans as simultaneously occupying the past and future. In Chang’s piece, we begin with the future and end with the past, leaving the present opaque and unknowable. It is in the opaque present, however, that we find perversion. Chang’s tears call attention not only to the persistent foreignness of the Asian American body and the impossibility of assimilation, but also to the possibility of pleasure in that space in between, a space that Shimikawa describes as “a movement between visibility and invisibility, foreignness and domestication/assimilation.”60 It is precisely this wavering between abjection, pleasure, and pleasure in abjection that exceeds the matrix of overdetermination and produces brown jouissance.

Temporalities of the Present and Brown Jouissance

While Bustamante and Chang perform different aspects of automaticity, what unites their versions of brown jouissance is that these performances occur in relation to the loop, which invites us to think about the relationship between sensation and temporality. By showing their performances in a loop, Bustamante and Chang keep them in the register of the present. Time does not advance beyond this moment of crying, which is repeated endlessly for visitors to the installation. In the case of Neapolitan this repetition amplifies the affective resonance of Bustmanete’s performance of crying. Instead of containing her tears to a few iterations of re-viewing Fresa y Chocolate, the loops bleed into each other to produce more hysteria and more melodrama. No matter when one begins watching, the cycle of tears feels endless. For Chang’s In Love the effect of this looping is more complicated. Since the two monitors show different loops, which may or may not be synced to each other, the viewer has varying understandings about the relationship between the onion and tears. This means that it is possible to watch the entire cycle so that the performances are juxtaposed, which means that one is always aware that the kisses are not kisses, but chewing. However, one could also enter at a moment when the onion is revealed, rendering the kiss a shocking outcome as the video starts again, or one could watch “from the beginning” and see the kiss turn into an onion. Although these scenarios embed the spectator within different narratives of what is at stake, each one relates Chang’s performance to perversion and crying. What shifts is whether the onion or the kiss is a cheap trick. Is Chang using the onion to produce the veneer of perversion or is the kiss an excessive cover-up for the onion? Either way, Chang’s excess falls within the realm of the perverse (even as that space may be the perversely unfunny).

That these larger loops speak to the tensions that emerge from the installations themselves is not surprising, but the doubled nature of these manipulations of temporality should give us pause. After all, Bustamante is also playing with looping within the video, while the force of Chang’s critique lies with her use of reverse temporality. Since I have been arguing that the forms of automaticity that Bustamante and Chang perform have to do with race and sexuality, I want to suggest that their disparate modes of staying in the present—through technological temporal manipulation—also have to do with race and sexuality and the temporal dimensions that they call forth. Generally, brown bodies are imagined as atavistic, which we see in Schuller’s discussion of nineteenth-century beliefs about sensation and evolutionary time. This is not an altogether unfamiliar argument. In Sensational Flesh, I made a similar set of claims. I argued, through a reading of Frantz Fanon, that black masculinity was seen as hewing to the temporality of the biological, which is to say that which is outside the temporality of civilization, while also arguing that black female sexuality could not be imagined as occurring outside the moment of chattel slavery. In these formulations, temporal stagnation was pernicious since it did not allow for agency or subjectivity. Bustamante’s and Chang’s suspension of progress, however, is doing something different.

Their loops foreclose narratives of progress and focus on the pleasures in dwelling on the unfinished. They also reorient the relationship between sensation and temporality. Rather than imagining that hysteria or perversion stop time, these bodily performances generate their own temporality, which is distinct from the conventionally narrativized time of progress in which there is a past-present-future. This is a temporality produced through the oscillation between subject and object. Bustamante and Chang mobilize the stagnation that the hysterical Latina and perverse Asian American woman inhabit and imbue it with their own affective energies. Through their theatrical amplifications of their modes of being objectified, Bustamante and Chang illuminate the subversive possibilities of the temporal stagnation that accompanies objectification. In Bustamante’s and Chang’s installations, the distinctions between past, present, and future blur into each other through the loop to suggest that brown jouissance carries with it its own sense of time related not to the external, but to the internal dimensions of sensation. In this way, we might imagine that Bustamante and Chang have created their own versions of reality in which reliving the impact—some might term it “trauma,” but I want to stay with the ambiguity of Bustamante’s and Chang’s assessments—of inhabiting the excess of a brown female body provides comfort, if not resolution or catharsis. This is the comfort of existing in the loop, of existing in repetition, of existing in an affective and emotional reality of one’s own choosing.

This temporality of brown jouissance is akin to one that Berlant describes as elliptical. In an interview in ArtForum, she describes elliptical thinking as thought that “both tracks concepts and allows for unfinishedness, inducing itself to become misshapen in the hope that by the time you return to the point of departure, so many things will have come into contact that the contours of the concept and the forms associated with its movement will have changed. How can our encounter with something become a scene of unlearning and engendering from within the very intensity of that encounter?”61 In Berlant’s description the unfinishedness of the ellipses enables her to unlearn what she thought she knew about something. Even as she returns to the beginning time and again, the narrative switches. Living in the present, even and perhaps especially when that present is self-created, is also about change even if it is not the same type of progressive shift that we have been trained to anticipate via repetition with a difference. Within any imagined stasis, there is always a dense thicket of possibility. This is where it becomes important that Bustamante and Chang refuse catharsis. In Bustamante’s endless crying, we see pleasure, grief, and masturbatory excess. In Chang’s narrative of kiss to onion, the questions of incest and masochism go unanswered, leaving us with a perverse opacity. These are particular pleasures that might disappear with more time or narrative. Instead, they remain contained in the loop—giving us space within the present to think with these repetitions and their pleasures, to think with sensation and to be in the time of brown jouissance and its multiple iterations of the present.