SILVER FACTORY FINALE

Andy never said “15 Minutes of Fame.” He just adopted it. He adopted everything. And every one.

—Louis Waldon

Robert Heide: Andy was good for some people, and not others. He was maybe helpful to some, destructive to others, but maybe some of these would have self-destructed anyway. In other words he was a conduit, so he inspired admiration just as he inspired enmity and hatred, and that’s sometimes the price of fame. It’s no accident that Andy is shot. When you become so famous, someone is always lying in wait to possibly …

* * *

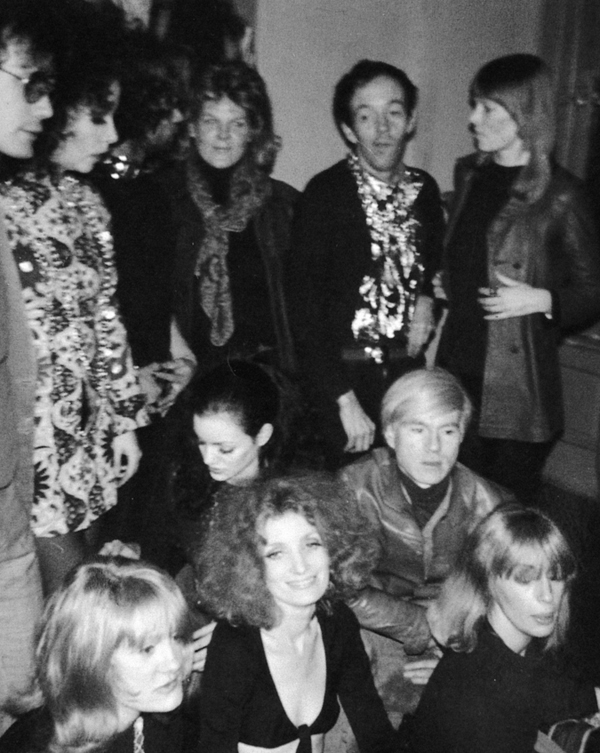

Bob Heide looked woebegone, and left the rest unsaid, but John Lennon was naturally uppermost in our minds. We had just visited with Jonas Mekas, down the street on 2nd Avenue at his Anthology Film Archives. Jonas had made a ‘home movie’ of Warhol with Lennon at a garden party, as they compared instant Polaroid shots and giggled together like kids in the sunshine, despite Warhol’s deep aversion to daylight and Yoko Ono. Here, he looked pale and skeletal, as if in need of a blood transfusion, while Lennon, deliriously happy, devours Japanese food and dances for the camera as Yoko clicks away. It was a private, poignant moment … Of course we used the footage. We’re filmmakers.

Jonas Mekas: (Martin) Scorsese always credits—I mean, he was there at the Film-Maker’s Cinematheque, seeing Warhol, seeing all the films. He was inspired and influenced. Influence is a very complex word. Influence can be part of the very climate, the people that you meet, and talk about the same kind of things. Just by talking or seeing what others are doing can clarify your own ideas.

Mary Woronov: Andy was a conduit. He really wasn’t interested in the things most people are interested in. The Velvet Underground—the songs were rebellious. The art was rebellious. So, you stayed there. But I believe after Warhol was shot, he was afraid, and he didn’t want to be so close to the raw kind of insanity that he wanted before. He knew it was different.

David Croland: It was the end of trust, the fear of selfishly thinking it could be me, because I was there that day … It was the end of a certain kind of innocent glamour. The glamour got harder, people got harder. They were scared after that.

Mary Woronov: It was scary, and so he stepped away. When he stepped away he lost part of his power, and he became the artist that he is. He didn’t do any more movies. Well, Paul helped him stop doing movies, because he took over.

Paul Morrissey: (from ‘Superstar in a Housedress’): So I mentioned it to Andy—I said, “I think they (Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis) should play women’s libbers,” like that ridiculous Valerie Solanas, who had shot him. Andy was very brave about it. He said, “That’s a good idea.”

Nat Finkelstein: Who walked away from that scene better than when they entered? People like Paul Morrissey, maybe Danny Fields. They were used, and then when they were used up, they were gone … Now Nico was different. She was self-sufficient, she was her own person. And she wasn’t going to be swayed by those people. I knew her past then. She visited me in Amsterdam. She was still pretty badly strung out. We had a discussion about if I were to rent a larger place in Amsterdam she could stay with me and I would help her. I never was into heroin.

* * *

Nat’s close friend Nico would always be into heroin, with side trips of LSD, and his love for her would remain unrequited. No longer part of The Velvet Underground, Nico left for the West Coast and the Monterey Pop Festival—and legendary rock star/poet Jim Morrison of The Doors, with whom she would have an intense affair.

Upon her return from Cannes and the ‘Chelsea Girls’ non-screening in 1967, Nico had found herself dropped from the Velvet Underground. (Photo: Nat Finkelstein)

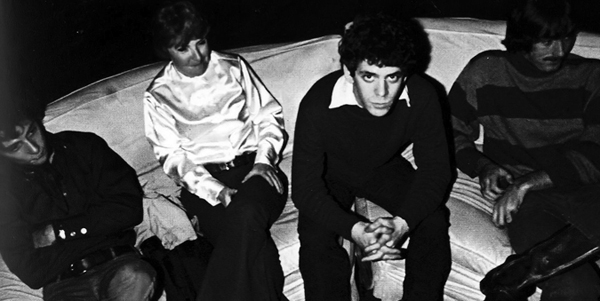

The Velvets prepare to pack it in at the Factory. (Photo: Billy Name)

Interviewer (to Nico)

Do you find that you’re swamped a lot, your days with the Velvet Underground and Lou Reed. Do you find you’re harassed by that?

Nico

I can’t say harassed. I just find it very tasteless, really. Because already that I’m still alive. I’m one amongst the few who are still alive, because I know that the audience likes clichés.

* * *

Nico’s drug use tended to distance her from Warhol, since he preferred talkers like Edie and Brigid and Viva. Nico tolerated me as a yapper, perhaps because I was also into acid, so long stretches of time could go by where no one would talk, but the brain synapses would be flying with no one the wiser. When interviewed at her concert in Manchester (an industrial town that she liked because it reminded her of Berlin), Nico was her usual circumspect self, which served the young filmmaker right, since his sound recording quality was god-awful.

* * *

Ivy Nicholson: I don’t think I communicated with any of the other actresses. Oh, Nico I really liked; she was the only one. We saw one another in Paris. She was like me, European. She was a friend, gave me advice. I was fascinated by her apartments. They were all magic, so weird—one totally black with only ashtrays. No paintings, nothing. Can you imagine? The only decor were ashtrays full of horrible cigarettes—a very elegant apartment with nothing in it. I think there might have been a mattress somewhere; I hope so. She lived there with (filmmaker) Phillipe Garell. Another was Moroccan, with different colored veils all over the walls. But again, no furniture.

Allen Midgette: In reality, much of the Silver Factory was a bit leaden more than silver. The toilet of course was also silver, but on the wall of the toilet, Ivy Nicholson had printed, “I’m in Paris once more with no money.” It’s those kinds of little things that you would want to capture, the fact that the windows are just factory windows looking out on the street, and not so clean—kind of dusty, kind of Miss Havisham from ‘Great Expectations.’ Great expectations were part of what the Factory was, what all these people had, what made you think of it as more glittering, and silvery.

Ultra Violet: You have to belong to somewhere, so that’s what held these people together, because we were all rebellious in our own way, rebelling against an establishment that is never right. Nothing is right in the world anyway, so the kids are trying to find an alternative, and that was part of the success of the Factory. T

Billy records a Family get-together.

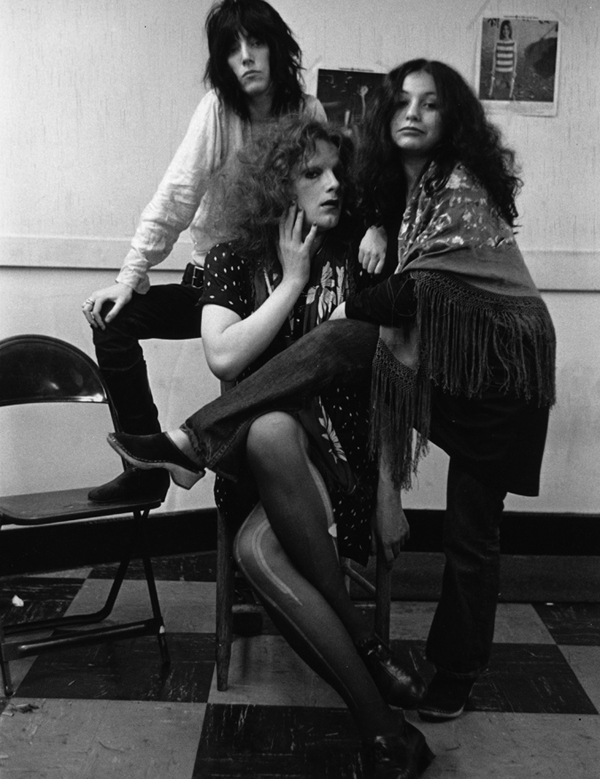

Poet-rocker Patti Smith, Superstar Jackie Curtis, and pal Penny Arcade pose for ‘Leee’ Black Childers.

Geraldine Smith: We were all younger than Viva and Ultra and Brigid. We were fifteen, sixteen. It was the most fun I ever had, I don’t regret anything. The parties! It wasn’t a party unless Andy was there. He was like one of these great puppeteers. Everyone wanted to perform for him. I really liked him; he was always nice to me. People blame him for not paying them, or for their mistakes, but they’re too negative. A lot of people think he exploited us, but others think it’s a stepping stone.

Ultra Violet: Tragedy happened, so things changed. Andy took risks, and he was pretty brave, I guess. And he only realized too late that this kind of thing had to stop if you wanted to stay alive. So, I think that belonging to the Factory … Factory is a powerful word. You manufacture things in a factory. We were being manufactured, or we self-manufactured ourselves.

Vincent Fremont: It got very dangerous when it almost took his life. Then, he changed, about who could get close to him. He was still very accessible … The craziness he was always attracted to, because he equated it with creativity. People think, “Oh, he got shot and now he can’t do anything anymore. He doesn’t want any crazy people around.” Well, they were just a different kind of crazy people. They looked different; they dressed differently. That was the beginning, where the drag queens and transvestites started coming to visit Andy—when you had Candy Darling, and the very talented Jackie Curtis, and Holly Woodlawn. So, it was a whole different era.

‘Leee’ Black Childers: The most beautiful young men on the planet were flocking to the Warhol Factory, where they could be made to feel more like men. Most of them were gay, so they had Jackie Curtis and Candy Darling to be their dates, covered in glitter, outrageous clothes … stuff they stole from dead people or out of garbage cans, stuck together with safety pins so they wouldn’t fall off. It all really did come off as very glamorous. It looked fabulous when they walked in a room, and they always had these beautiful boys with them. Andy loved that. The only problem was very few of them had any talent other than just wearing garbage on their back and getting out on the streets. They couldn’t act. They didn’t want to.

* * *

Mr. Childers’ ribald Chaucerian Canterbury tales of his exotic roommates would have made wonderful little period movies all by themselves, because the drag queens really sparkled in those early Paul Morrissey films. And, thanks to Andy, the serious actresses who’d found themselves out of favor at the Factory, would also become cult queens …

Mary Woronov: After Warhol, I got very, very strange roles—‘Eating Raoul’ where I was a mass murderer, or ‘Rock n’ Roll High School,’ where I was this aging, viciously unsexual school principal. I got a following because I am a good little camp actress, and so now I am a cult queen as you would put it, in Hollywood terms. Well, maybe not Hollywood terms—they do not like cults—but I am an aging cult queen.

* * *

Mary, still working on her doc, is in demand on the lecture circuit and was honored with a retrospective of her films and a Lifetime Achievement award in Hollywood. We shared dinner and a good bottle of wine, so I guess her liver has fully recovered from her feckless youth with Warhol … Louis Waldon had mentioned that after the Factory, she’d married and moved to Italy: “Like most people, she didn’t want to have anything to do with Andy. Nobody wanted to be identified with Andy. They thought it was bad karma.” Out of loyalty, Louis stuck around for a bit longer before he, too, eventually decamped to Europe.

* * *

Louis Waldon: I made Andy’s last movie. He got out of the hospital and we made that movie. But this dread that hung over Andy—people really hated him! Because of Pop art. Here were these people struggling to make a new art movement in New York City. The last art movement (Abstract Expressionism) had been Jackson Pollack and those other guys, Yves Kline, all them. They hated him! He was menaced by a lot of crazy people. He got shot at several times. Then he got shot for real, and he told me he died. He said, “I died, Louis. The light at the end of the tunnel went out.”

* * *

The light had indeed gone out for a while. Warhol had been pronounced clinically dead six minutes after arriving in the emergency room of Columbus Hospital. According to Louis Waldon, surgeon Giuseppe Rossi had to cut open Warhol’s chest and literally massage the heart to get a beat. Outside the surgery, Louis tried futilely to keep Ivy Nicholson from holding her own tribal last rites, dancing and screaming for Warhol at the top of her lungs. For all we know, she may have actually had something to do with his miraculous rally—if only to get away from her … The last movie Louis made with Warhol was ‘Blue Movie.’ As Billy Name told us, “We were pre-porn, but we did the first ‘fuck movie’ with Viva and Louis Waldon actually fucking in the movie. But it was shown and seized by the City of New York.” The film was Viva’s idea, and consisted of the couple meeting, having sex, and enjoying a lengthy post-coital conversation. ‘Blue Movie’ would turn out to be Viva’s swan song at the Factory. She left New York for Paris and French actor Pierre Clementi …

Ivy Nicholson, in her dancing shroud, poses for Billy’s omnipresent camera.

Viva: Timothy Leary loved ‘Blue Movie’ … Gene Youngblood (L. A. film critic) did, too. He said I was better than Vanessa Redgrave, and it was the first time a real movie star had made love on the screen. It was a real breakthrough.

* * *

According to biographer Victor Bockris, Viva had been initially appalled by the rushes for ‘Blue Movie,’ especially the sex scene, but not for the obvious reasons. She had thought the scene “flat and perfunctory,” though she and Louis did, indeed, do the deed. Warhol had to plead with her for a release. Viva also recalled that after Warhol was shot, “He was very much changed toward me. Much cooler. He was sexually afraid of women before, I mean you couldn’t touch him; he would cringe. But afterwards he seemed to be deeply afraid.”

* * *

Victor Bockris: After Valerie Solanas shot him, Andy became frightened of crazy women, and he remained frightened of crazy women for the rest of his life. His mother was a crazy woman in a way—there was a lot of craziness in the female side of his family. So Valerie just really scared him. Still, he was worried that after the shooting he wouldn’t be able to have ideas, because he depended so much on crazy people for ideas.

Billy Name: You couldn’t expect him to be the same Andy that he was before the shooting. I felt the trauma of this whole thing so much that I stayed in my dark room, and I only came out at night. I could not be light-hearted. And Andy made believe he was … It was a cardboard Andy. It wasn’t a real Andy anymore.

Andy Warhol: Before I got shot, I always thought … that I was watching TV instead of living life. Right when I was being shot and ever since, I knew that I was watching television.

* * *

Billy Name mentioned that Warhol once said, “I’m not afraid to die. I just don’t want to be around when it happens.” … Billy himself would not be around for that much longer to worry about his friend and mentor. He had been cloistered in his dark room for over a year, studying Tibetan Buddhism (one of us!) and meditating, living on take-out and Campbell’s soup. Since he was rarely sighted, he’d achieved near mythic status, and was spoken of in hushed tones around the spiffy new ‘Black and White’ Factory by those who feared he might die in there, and the headlines would read, ‘Andy Warhol Locks Man in Toilet.’

Fred Hughes, Andy, Viva, and Brigid Berlin take (gasp!) public transportation. Or is it a plug for Delta Airlines?

Andy and Paul in the Union Square Factory putting finishing touches on a film, using my old editing machine, the defunct moviola. Twins Jed and Jay Johnson in B.G. (Photos: Billy Name)

Gerard Malanga: Andy had moved out of the Silver Factory toward the end of December ’67. Paul Morrissey wanted to give Andy’s image a cleaner look, and one of the things was to convince Andy we had to be more business-like. We had to have desks and a clean space and shiny floors, and, you know, no more silver dust floating around. And we had to get rid of the freaks. Paul was the instigator for getting rid of Ondine, getting rid of Barbara Rubin, getting rid of Billy Name, ultimately probably getting rid of me! I mean, I am still friends with Paul, but let’s keep history, let’s keep the historical thing in context. Paul saw Andy’s potential, rightfully so, but he felt that Andy needed a new image, so basically it was a make-over, a Hollywood make-over. And Andy went along with it. Andy had a good sense and scent for money, and he smelled money, or at least he was dreaming about money. So he probably said, “Well, let’s give it a try.”

Billy Name: We had a contract to provide a new soft-core porn ‘art film’ each month for the Hudson Theater on Times Square. ‘Bike Boy,’ starring Viva, was one which we did. Then Andy was shot, and he wasn’t able to do it anymore. But we had a contract, so Paul started making his Joe Dallesandro pictures—‘Flesh’ and ‘Trash’ and all these things. If Andy hadn’t been shot it never would have happened … Andy would have continued making Andy Warhol Films, but because he was incapacitated, and we had the contract, Paul took over the camerawork and direction. Well, a lot of people don’t know a lot of things.

Geraldine Smith: Paul. Paul. Paul. I loved him, he’s a character, a really smart, talented guy. He’s very opinionated, he’s very loyal, and I like his movies. They’re different from anything else, really controversial. I had a crush on Paul as a kid. We all had crushes on Paul. We all thought he was fabulous. When I starred in ‘Flesh’ opposite Joe Dallesandro, I said, “Paul, where’s the script?” He said, “There is no script.” I had to make the whole thing up! So, I just improvised. I was going to be married to Joe and I had this lesbian girlfriend. And I wanted him to go out and hustle to bring some money home for us. We were friends, we hung out together, we didn’t think for one second about anything. Just did it. We did the whole movie on improvisation.

* * *

‘Flesh,’ ‘Trash,’ ‘Women in Revolt,’ and ‘Heat,’ which also featured Warhol favorites Holly, Candy, and Jackie, are films worth watching today, not just for the historical value, but because they’re actually entertaining. Seeing them in New York all those decades ago made one feel cool and cutting edge. And also perhaps because you could run into its stars on a regular basis while bar-hopping.

Foreplay … Viva, vivacious star of ‘Bike Boy,’ gets Joe Spencer in the mood.

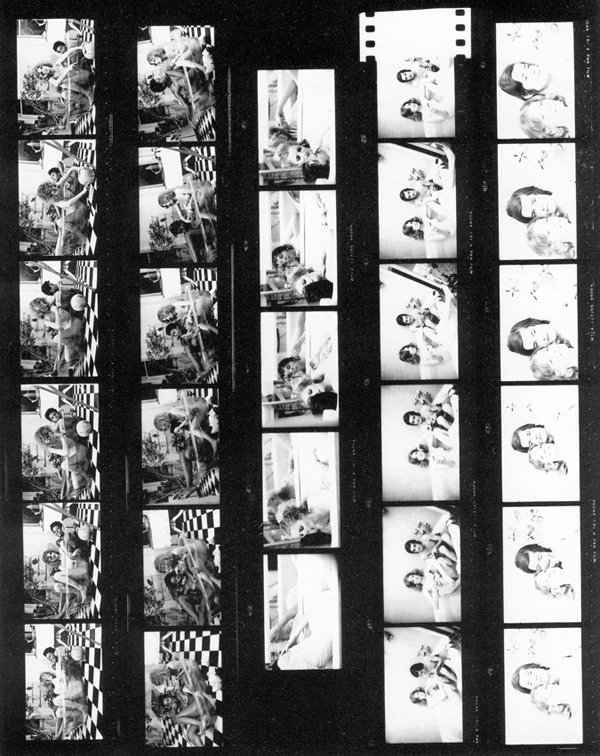

Post-coital regrets? … The couch seems to have taken a direct hit. Part of a series shot by Billy Name during filming of ‘Bike Boy.’

Billy Name’s contact sheets for ‘Bike Boy’ and ‘Tub Girls.’

* * *

‘Flesh’ came about as a reaction to John Schlesinger’s film ‘Midnight Cowboy,’ which had borrowed liberally from Warhol movies, even using his people, like Viva and Ultra Violet, for a party scene to represent life in the Factory. Warhol was flattered that Hollywood was at last being influenced by his films, but also a bit envious. He suggested that they “make another ‘Hustler’ movie.” The film, ‘Flesh,’ directed by Morrissey, featured Geraldine Smith, Patti D’Arbanville, and Joe Dallesandro, an eighteen-year-old discovery whose presence in ‘Loves of Ondine’ had assured roles in ‘Lonesome Cowboys’ and ‘San Diego Surf.’ Warhol, slowly recovering and happy to take a back seat, felt safer with these teenagers than with the dangerous divas that had dominated the Silver Factory years.

* * *

Ivy Nicholson: Everything was unusual with Andy. One of the strangest things that happened—of course you know that I am in love with him—he told us to go to the prison. Paul chose the courtroom for this movie, which wound up being called ‘Love On Trial.’ I started directing, having never directed in my entire life! I invented different kinds of love for the actors. Like one guy, Rene Ricard, did self-love while my boyfriend and Andy’s ghost would pass in front of the judge wearing underwear.

* * *

Louis Waldon felt that Andy was weary of the histrionics. But his own experiences of fending off the temperamental flora and fauna that thrived in the Factory hothouse led Louis to a startling conclusion: Warhol, so shy about his looks that he preferred hiding “in the shadows” and watching others, craved that spotlight himself …

* * *

Louis Waldon: Andy wanted to be an actor, wanted to be in the movies—he was a real fan. Paul Morrissey wasn’t. Paul Morrissey was in to take over the Factory, take over the filming, which he finally did. Paul went into transsexuals and transvestites, and young people. He got rid of all us older people. We all left and went to Europe.

Dave Croland: People get in a corner. They have this life, up there, then they move somewhere else. There are ghosts around New York. People come back who were in that scene, and become shaky—the dichotomy of what it was, and what their life is now. So they lead quiet lives. I am still living a glamorous life in New York. I see Gerard Malanga, Joe Dallesandro. We talk about cerebral things. Andy used to say, “If you want to know about me, look at the surface of my paintings.” What does that mean? I look with the surface of my eyes. One can see if I’m telling the truth or not.

Taylor Mead and Louis Waldon, off to Europe once again, share a meal at Max’s Kansas City. The two longtime friends and co-stars died of strokes in 2013.

The new kid in town, ‘Little Joe’ Dallesandro, had already worked with Taylor and Louis in ‘Lonesome Cowboys’ and ‘San Diego Surf’ when he moved into starring roles in Paul Morrissey’s ‘Flesh,’ ‘Trash,’ and ‘Heat.’ (Photos: Billy Name)

Interviewer (to Warhol)

You said all people are the same and that you wanted to be a machine in your painting, is that true?

Andy Warhol (to Brigid Berlin)

Uh, is it true, Brigid?

Brigid Berlin

No, he just wishes it were all easier.

Taylor Mead: After he was shot the energy level went somewhere else. Then, Brigid was keeping books. Brigid Berlin was his secretary. I made a couple of movies with her where she was fantastic, but I think she had her party list, and we were all off the list. She was controlling all that. So, we were off the list of Andy’s parties and dinners and stuff, and I think that it had to do with Brigid. But Andy would just let this all happen. He just let everyone do their own thing.

* * *

With linebacker Brigid Berlin running interference, Warhol could continue that laissez-faire illusion. Although many women had tried to coax Warhol into the marital bed, Brigid was the wife figure in Warhol’s life. According to Vincent Fremont, who worked closely with Andy and became director for The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, “Brigid was the only one who could yell at him. They would really torture each other, but like a loving married couple.” According to Viva, “They had the longest running marriage in New York.”

* * *

Brigid Berlin: I didn’t want his art for Christmas. What I wanted was a vacuum cleaner.

* * *

Warhol would, of course, always have a soft spot for the lads. In the footage we used from Torbet’s ‘Andy Superartist,’ Warhol was interviewed by a youngster who wanted to “play a game” with him, and Warhol cheerfully went along. The boy began with a statement: “I find that people are—” Warhol, cracking a rare smile, said, “I find that people are—fantastic.” The last question asked of him, recorded years before his shooting, was: “The most wonderful thing about living—” Without skipping a beat, Warhol answered, “the most wonderful thing about living—is to be dead,” His jaunty reply shocked many. But was not a bit surprising to those who knew him …

Brigid Berlin and the only person who ever gave her a job. (Photos: Billy Name)

Best friends forever. Brigid and Andy gossiped about everything, every day, and their mutual insights would eventually wind their way into books, films, and history.