AFTER THE FACTORY

… EPILOGUE

The most wonderful thing about living is to be dead.

—Andy Warhol

Victor Bockris: Somebody said about Warhol that “Great artists make art out of what creates the most distress for them.” I think that’s very true, and a very good point. You can really follow Warhol’s work and see how he is facing the things that cause him the most distress. And ultimately his theme is death … The death of his father when he was twelve, the near death of his mother when he was thirteen, left indelibly imprinted on him the horror of hospitals and how quickly someone can just disappear. Also, the horror of death in the religious tradition, where you bring the very big thing to him, a big thing in his life, death.

Henry Geldzahler: He wouldn’t fall asleep until dawn cracked because sleep equals death … Andy was a Catholic and I think he had a sense of evil. His position was not a profoundly moral one—he surrounded himself with all kinds of things that society and the church disapproved of. And perhaps, finally, he disapproved of. That was one of the fascinating and repelling aspects of his films and life at the Factory.

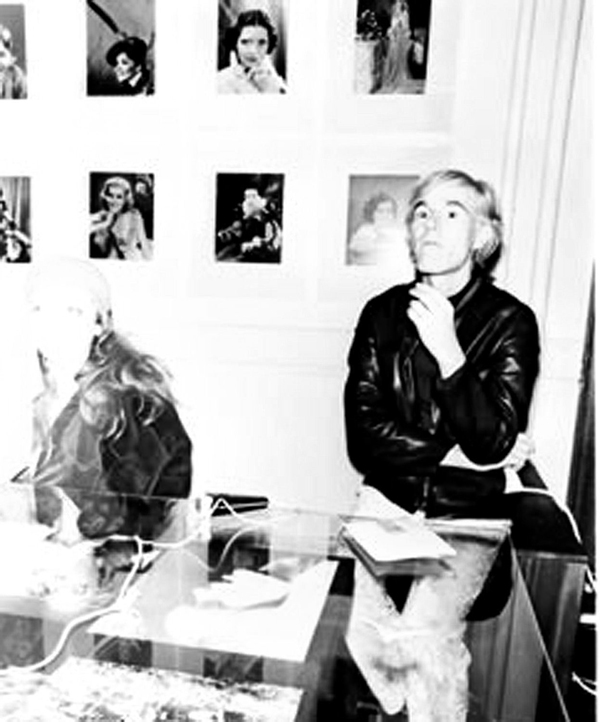

Andy, Viva, and other former goddesses of the silver screen share a moment in the White Factory. (Photo: Billy Name)

Robert Heide: After he was shot, I met him on MacDougal Street. He was very frail at that point. Andy was not just super cool, he was also very vulnerable. He was at the cutting edge of the age that we live in now, of technology … In the future we will not want our fifteen minutes of fame. We’ll pay dearly for our anonymity.

Louis Waldon: I came back from Europe after I hit the cover of the Village Voice with Viva and Brigid Berlin. At a book opening, I walked into the author’s bar at the Lion’s Head with a buddy of mine. We ordered a drink, and a bartender came out, who was a writer I had known for years. He poured a drink, then he poured himself a drink—and spat it in my face. I said, “What the hell is this about?” My buddy says, “Let’s get out of here. These people don’t like you, Louis.” It was because I was on the cover with Andy Warhol.

Ivy Nicholson: I would have been Andy’s wife. He had a long time to think about it. That was during my homeless period. I got more publicity when I became homeless than when I lived in my first husband’s castle! I was a countess, married to Regis Du Poleon—not much publicity there. But when I became homeless, it was covered by the Washington Post, The Times. People were flying in from all over to try to find me, a homeless woman! Someone wanted to be my agent, but I was still homeless. So I said, “Okay, I’ll show up if you invite some of my homeless friends to the Fairchild.” They would! I’d drag in some other homeless guy who was a starving artist, as they say.

* * *

It’s ironic that Ivy in the sixties made much more money as a model than Warhol did selling art. When we interviewed her in Paris, she came with a retinue, including her charming son, the Viscount Darius Du Poleon (Yes, those stories of her castle were true). Young Darius had appeared in a couple of Warhol films, but Ivy was hardly a hovering stage mom. Also along for the Paris visit were her adult twins by another former husband, the filmmaker John Palmer (‘Empire,’ ‘Ciao Manhattan!’). We drank red wine while she recounted her escapades, sometimes a bit incoherently, reminding one of an unpredictable, very bright bag lady. Then, she decided she’d like to spend the night, and I realized Ivy was homeless once more …

* * *

Ivy Nicholson: When you live in the street and you don’t always have enough to eat it’s a real thrill going to have a wonderful meal. You can order the most expensive wine with the most expensive food!

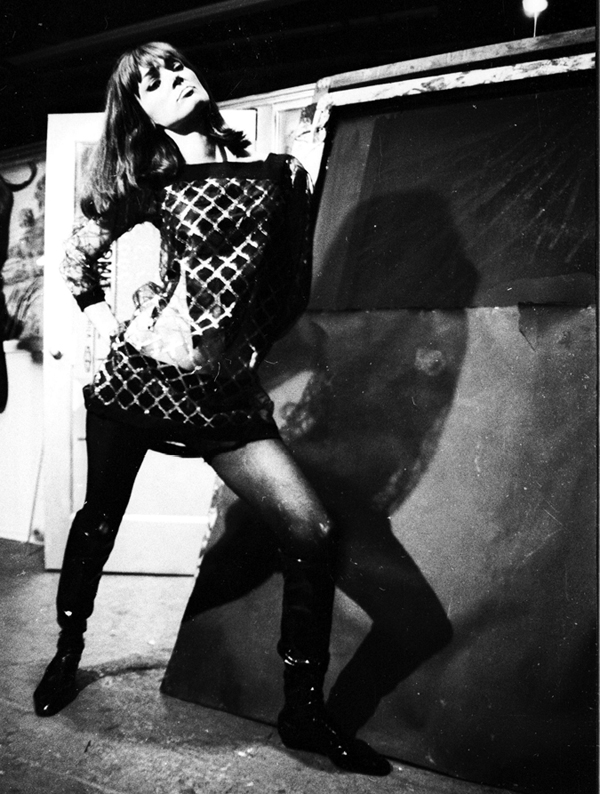

Billy shoots Ivy and art in the Silver Factory.

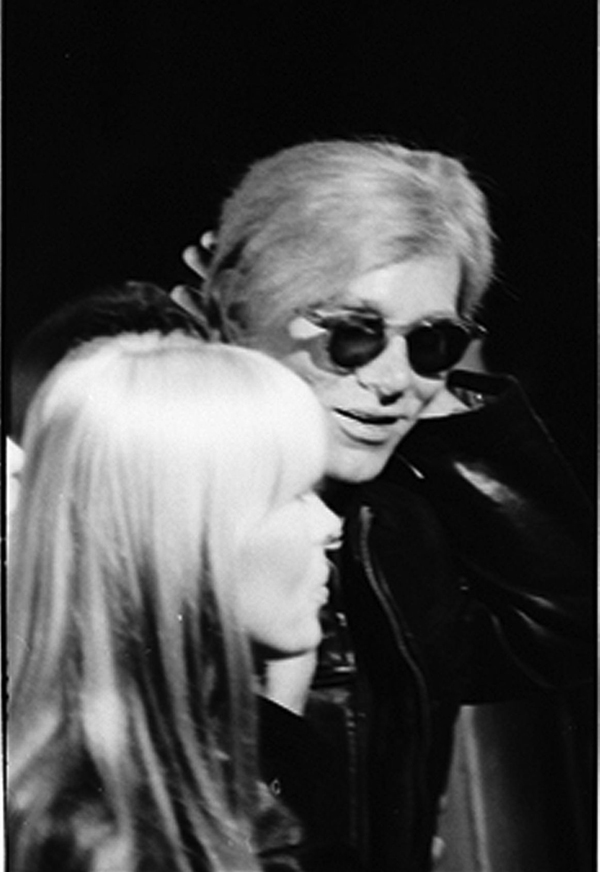

“I’ll be your mirror.” Andy and Nico. (Photo: Billy Name)

* * *

… Ivy is still a whirligig of manic energy, but manages to somehow hold it together, and has recently (relatively speaking) directed a film starring her twins, who are supposedly schizophrenic, but very sweet. We also talked about our mutual friend Nico, and the last time we’d seen her before her untimely demise in 1988 at the age of 50. She’d apparently had a heart attack, and had fallen from her bike and hit her head, suffering a brain hemorrhage by the side of a dusty road in Ibiza, Spain. After the Velvets, Nico had done a solo album, ‘Chelsea Girl.’ She and John Cale also created the wondrous ‘The Marble Index.’ But I will always think of her (and Andy) when I hear ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties.’ Warhol also adored the haunting ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror,’ since he’d so wanted to be Nico, his Nordic goddess Girl of the Year. He’d compared her to the prow of a Viking ship. Nico clearly wanted calmer waters.

* * *

Nico: Regrets? I have no regrets, no, except that I was born a man instead of a woman. That’s my only regret. (She laughs and inhales her unfiltered cigarette.)

Lou Reed: (strums his guitar in studio) “It’s such a perfect day, you made me forget myself, made me feel I was someone else, someone good …”

* * *

In 1967 Lou Reed dedicated his song ‘European Son’ to Syracuse University mentor Delmore Schwartz, who had died the year before at age 52, a sad alcoholic. The Velvets made their last group appearance at Max’s in 1970. I remember them playing ‘Perfect Day’ in the upstairs room … Warhol had already lost them. His involvement and interest had waned by ’67, when their album, ‘The Velvet Underground and Nico’ was finally released by MGM-Verve. In the era of ‘Sergeant Pepper’ and the ‘Summer of Love,’ their dark, edgy compositions lent a discordant note. Even Warhol’s cheerful peel-off banana on the cover could not help. Nico had left, John Cale had left, and Lou Reed was ready for the solo career that would take him all over the world and introduce him to a new generation of fans. In 1991, we walked from our atelier in Paris to the nearby Fondation Cartier to see Lou and John play together again, reunited thanks to Billy Name. They sang ‘Songs for Drella.’ C’était incroyable. Almost 20 years after that, we saw Lou Reed once again in Paris, performing ‘Berlin’ to an oversold house. Though suffering from liver disease, he looked much the same. Come to think of it, so did we. Time stands still in Paris …

Lou Reed: (Andy) made it all possible, one, by his backing, and two, before we went into the studio, he said, “Use all the dirty words. Don’t let them clean a thing.”

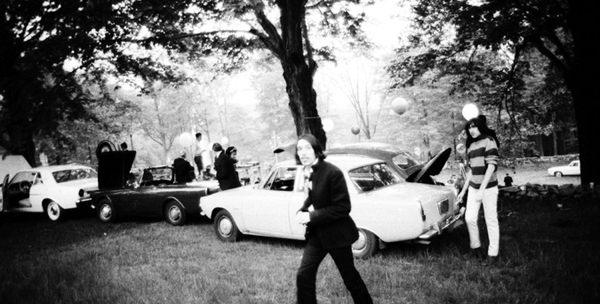

The Velvet Underground arrives for their performance at the famous Philip Johnson ‘Glass House,’ built in 1949, in New Canaan, Connecticut on 47 acres.

“Such a perfect day.” John Cale enjoying a bit of bucolic in the Connecticut woods with Gerard and Nico. (Photos: Billy Name)

Bibbe Hansen: We all lived in loft buildings. They were old factories. Growing up in the art world, to a certain extent art isn’t anything special. It’s what you do every day. One time, I was in my father’s loft, starving to death, and I went down and found some soup. Al (Hansen) came home a little while later and asked me if I was hungry. I said, “No, I just had some soup.” He fished the cans out of the garbage and said, “Do you know what this is?” I said, “Yeah, Campbell’s Tomato soup.” … “No! That was an Andy Warhol signature. You just ate two cans of soup signed by Andy Warhol.” So, they say when you are really, really hungry food tastes great. Let me tell you, it tastes even better when you are really, really hungry. And, it is art.

Mary Woronov: I don’t care for Pop art. I mean, when I was there I thought it was gold. I thought it was fabulous, and I didn’t understand what was going on. I was just one of the little flies on the wall going, “Oh this is fabulous, oh wow, a soup can, ha ha ha!” I hate it now.

Gerard Malanga: Andy did something really interesting, although some of the other Pop artists did the same thing to a certain extent, had similar ideas. There was a convergence of those ideas, and that was because of the media. In a sense, the media created Pop art—it became a mirror to the media. The story of Pop art is really the story of the media looking at itself.

* * *

Gerard might agree that it could also be Warhol looking at himself—he was fond of self-portraits. The first one he ever made, in 1963, went in 2011 for $38.4 million in a bidding war. As art critic Peter Schjeldahl wrote in the May 2000 issue of The New Yorker: “In Warhol’s case, we should acknowledge just how right he got the big changes, and, no less, the big continuities of life on a media-revolutionized planet. His best works of the early sixties flag the exact moment when it was no longer possible to regard mass culture as a sphere of kitsch, remote form the values of serious folk.” … Bob Heide concurs, since he shopped a lot with Warhol. When we visited a friend who had bought Warhol’s townhouse, the word “Hoarder” came up.

* * *

Robert Heide: Andy was cultured. We’d go to flea markets together. Of course, Holly Woodlawn would also be selling at the market with stubble on her face, hung-over. I had a sign in my apartment from 1947, Betty the Coke girl, with her bright red lips and brown hair. Drink Coca-Cola! Andy said, “That’s the real Pop art.” People call it nostalgia. I think it’s classic Americana. Everything is art, when you’re dead and gone. Andy and me, we were archeologists. We weren’t about the money.

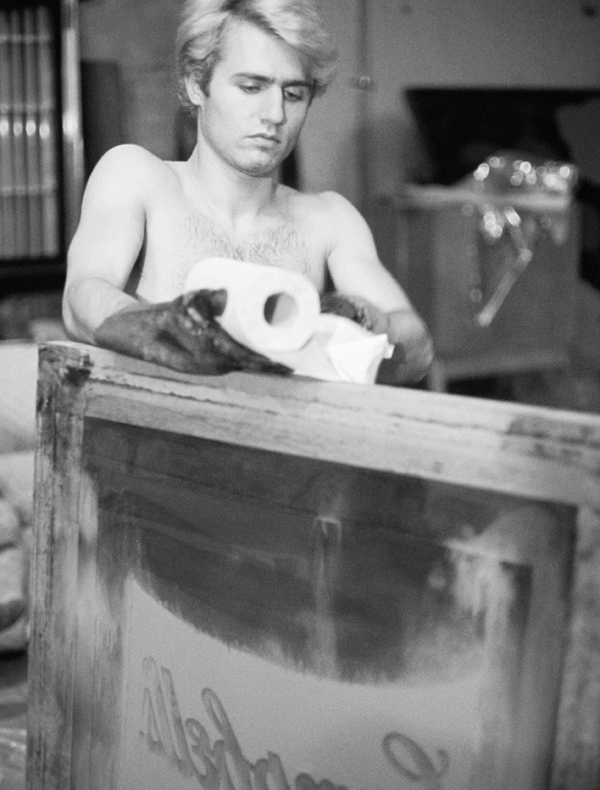

Messy work … Gerard silk-screens Campbell Soup Cans. (Photo: Nat Finkelstein)

Vincent Fremont: Andy was the center. He was the force. He said he was just there paying the rent, watching other people do things. That is again the opposite. He was like a huge magnet of ideas and exchange of ideas. That is what life is about, and Andy understood this.

Nat Finkelstein: Whoa, whoa, another kind of Andy Warhol? When you look at it, society in general, what effect did Andy really have? The people around Warhol were a facade, salesmen of toys and titillation. They were a safety valve for society. Think about all the photographs you’ve seen taken around the Factory, and think about how many people of color you saw before 1969. None.* Sure, there were blacks around, but they didn’t get into the Factory—there was only one water fountain. So what effect did Andy have, aside from being just a large rock which was thrown into a pool and made a lot of ripples? The structure remains intact.

* * *

Andy Warhol: I’d asked around ten or fifteen people for suggestions. Finally one lady friend asked the right question, “Well, what do you love most?” That’s how I started painting money.

* * *

A close Warhol pal with little interest in money is still working well into his eighties. Jonas Mekas championed Warhol’s movies, and today his Anthology Film Archives is one of the world’s largest and most important repositories of avant-garde films. I wish he could find the time to teach a film course at NYU’s graduate film school …

Jonas Mekas: People think, “Why should we see those films?” Consider, in the old days people used to go and make dangerous long trips into the Orient and bring back spices to enrich the kitchens of Europe, something special they could not find at home. And the same purpose is to show films. They don’t have to be great, but they each contain something special and local that we don’t have. Every country has cinema, but it’s very specific, related to their country, and we should be interested in them. That is what we are all about here at Anthology (Film Archives). We show films that nobody else would show. They don’t have to be masterpieces. It’s like if you just eat a steak every day and no salad. You sometimes need salad. You cannot live on masterpieces alone! So, that said, you go to Eisenstein, to Renoir, to Rossellini, and nobody can make films like Renoir, nobody can make films like Eisenstein, and nobody can make films like Andy. He used everybody around him to produce that whole body of work, that cannot be repeated. It cannot be repeated.

Interviewer (to Warhol)

When they tried to explain your film, they said “This was a peek into Hell.” For me, William Burroughs’ ‘Naked Lunch’ is like a peek into Hell.

Henry Geldzahler

Andy goes to Church every Sunday, and he probably has his own idea about Hell … (turns to Warhol) Does Chelsea Girls remind you of Hell?

Andy Warhol

Uh, no.

Henry Geldzahler

Were you surprised when critics wrote that?

Andy Warhol

Uh, yes.

* * *

Award-winning filmmaker and Burroughs pal, Jean-Francois Valee (yes, he’s French) made a must-see movie that gets under the skin as effectively as a plunged needle. For the above interview we used a hallucinatory clip of Burroughs unearthing his heroin stash from the bathroom of a wretched Mexican hotel room. The film features an interview with Laurie Anderson, extraordinary musician and performance artist, who waltzes with Burroughs, both snappily attired in identical white linen suits. In the Nov. 6. 2013 issue of Rolling Stone, Laurie wrote a beautiful and moving eulogy to her husband and soulmate of 21 years, Lou Reed.

Donyale Luna (the first black ‘Supermodel’), Gerard, Ingrid Superstar, Danny Williams, and Andy Warhol pose for Nat Finkelstein’s camera.

Actor Paul Swann stars in ‘Camp’ (1965) with Gerard Malanga. Other cast members included Tally Brown, Fu Fu Smith, Tosh Carillo, Jack Smith, Mario Montez, Baby Jane Holzer, Judie Babs. (Photo: Steve Schapiro)

Vincent Fremont: Andy was attacked as an artist throughout his career. He would get a showing in the Leo Castelli Gallery, but Leo didn’t really understand him. He was more focused on Jasper Johns, Lichtenstein and Rauschenberg. Andy actually started creating his own gallery—the Studio. Fred Hughes comes into his life in 1967 and turns it into what he wants to be done, where they are working with various dealers. Leo was a New York dealer, but there were others in Europe.

* * *

Gallery owner Leo Castelli said that his job consisted, on a daily basis, of contributing to “the myth-making of myth material.” His first wife Ileana Sonnabend had been an early champion of Warhol, with shows at her galleries in Paris and Soho. A year after her death in 2007, the heirs got hit with a 50% estate tax, so they sold off $600 million worth of her $1 billion dollar art collection, including 4 Warhol Marilyns, 3 from his Death and Disaster series, 2 Elizabeth Taylors, and a partridge in a pear tree … I have made some small attempt here to note the Warholian flurries in the market, but it’s quite impossible to keep up with records that keep breaking themselves. He reigns as the biggest auction seller from 2012 to 2015. Warhols are for sale everywhere, though some art critics wonder “how long his magic will last,” the question no one dares answer. It’s a pity that all those Factory People we interviewed decided back then to “take the hundred dollars” and not his art. If only they had listened to Ivan Karp, Warhol’s first dealer, who’d always had faith in him. But then, they’d have had no time for us, being too busy with their investment portfolios.

* * *

Nat Finkelstein: Andy was broke until the seventies. He would complain. When Fred (Hughes) came in, he commercialized it and gave Andy a direction where he could be financially enabled. But as far as the sixties were concerned, that Andy was just sort of evolving? No. There were three different corporations formed under his name, at least three that I know of, so he wasn’t evolving.

* * *

Fredrick W. Hughes was to become the most important person in Warhol’s life. Then a dapper self-possessed twenty-two year old, Hughes had been working since a teenager for the powerful de Menil family, the greatest art collectors in America. (Warhol often filmed on their lavish estate, including, ‘Loves of Ondine.’) So, he was absolutely all about Warhol’s art, selling off the stockpile and getting him into portraits. Another staff member, nineteen-year old Vincent Fremont, would soon replace Billy Name as the (White) Factory foreman, running ‘the business’ and becoming vice-president of Andy Warhol Enterprise.

Billy photographs Ivan Karp, longtime Warhol art dealer.

Vincent Fremont: Andy ran his own business … I didn’t go to college—I went to the University of Andy Warhol. You learned a lot. What was the most important thing I learned from Andy? I don’t think there is just one thing. It’s multiple life lessons, being close to an artist that way. He was the godfather to my first daughter. As far as working, even though he was a workaholic, he made it fun, at least for himself, and every day was not a walk in the park.

* * *

According to most of our interview subjects, Warhol had indeed made the work fun for himself and his Factory People. But when the scene stopped being fun, perhaps it was time to ‘step out of the picture’ and go for a walk in Washington Square Park, and just keep going—which is exactly what Billy Name did. He had treasured his time with Warhol, as evident in those fabulous fly-on-the-wall photographs. Some other folk we met made me want to say, “Hey, you with the airs, one day you’re going to realize that time has moved on without you and it’s all gone, the glamour, glory, and silver glitter.” Billy knew better, being a Buddhist and aware of the benefits of non-attachment. In his seventies and suffering from diabetes, Billy can be reclusive these days, but on November 6, 2014, he was honored with an opening at the Milk Gallery in Chelsea to celebrate ‘Billy Name, The Silver Age,’ a limited edition art publication of his best pictures, and we were happy to be of some help.

Billy Name: There was not really a place for me anymore. It was simply an art scene. So I left one day and I left a note on the darkroom door: “Dear Andy, I am not here anymore, but I am fine, love Billy.” And I went out into the world to see what the planet Earth was doing.

* * *

While Billy had quietly lived in his little darkroom, the only person to visit him had been his friend Lou Reed. Apparently, Warhol had gotten used to the situation …

* * *

Andy Warhol: I had no idea what made him go in, so how could I get him to come out?

Gerard Malanga: (to Billy Name) You don’t know what happened the day after you moved out? Paul and I went into your room. You know what Paul started doing? He started dancing an Irish jig.

Billy Name: Oh, I know. He didn’t want me to be back there from the beginning of the second Factory in Union Square. He would tell Andy things like “Oh, Billy can’t stay there because he’ll paint the whole place silver.” So, I left the note, and just left.

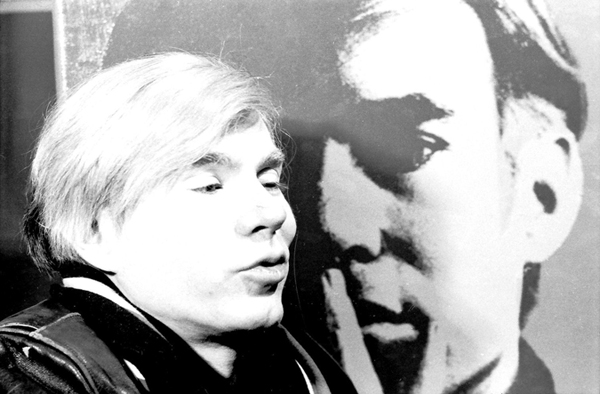

In the Silver Factory, Andy communes with his famous self-portrait. Billy Name’s impromptu shots of Andy gave us insight into more than complex personality.

Billy channels William Eggleston in the stark darkroom where he lived for eighteen months, in the Black and White Factory.

Gerard Malanga (to Billy Name): Paul was so elated and thrilled at the fact that you had vacated, his albatross.

Billy Name: I never came back. I was living in the streets in the Village, but they knew me at the Paradox on the Lower East Side, and they always let me eat there free. But I enjoyed staying out in the park, and I slept in hallways and in cardboard boxes and hung out with people living in the streets. Eventually, I went down to this farm in Georgia, then New Orleans, then Colorado, then San Francisco, then …

Danny Fields: They were too much, really full of moxie, forcing Billy out. But you know what, he went into a lovely life in upstate New York, and he became the mayor and the chairman of the Beaver Dam Commission and all that. He totally changed his life and he became a country boy and a political ecologist and all kinds of things. A lot of the stuff that I’m telling you, excuse me, but he’s alive and Andy’s dead.

Andy Warhol: I always thought I’d like my own tombstone to be blank. No epitaph, and no name. Well, actually, I’d like it to say ‘figment.’

* * *

According to art critic Peter Schjeldahl: “Warhol’s greatest moment was brief. Caught in the feedback of his own influence, he declined rapidly as an artist. But his peak performance stands higher and higher, while everything that once seemed to contest it falls away.”

* * *

Billy Name: We were aware at the Factory what we were. We could feel the power, the dynamic of the whole thing, being in the hot spot of the art world. I didn’t really have an intent to document … I was just an artist who Andy gave a camera to. But we were of the avant-garde mindset, too. We admired the poets in the late fifties and early sixties in New York culture. Then it moved into experimental music, with John Cage and La Monte Young, and experimental film with Jonas Mekas. Andy didn’t know that world. He got into the commercial art world when he came to Manhattan, but we were in the legitimate avant-garde, Gerard and I. We stemmed from there, so we opened roadways for Andy to come into it, where he could be comfortable.

Gerard Malanga: Well, it became an interesting thing for you to photograph.

Billy Name: Yeah, but it was more like a dance for me than an attempt to document. I would shoot on the sets; do shots of Nico for the album cover. Or the Velvet Underground. Otherwise, it was dancing all of the time with the camera in my hand.

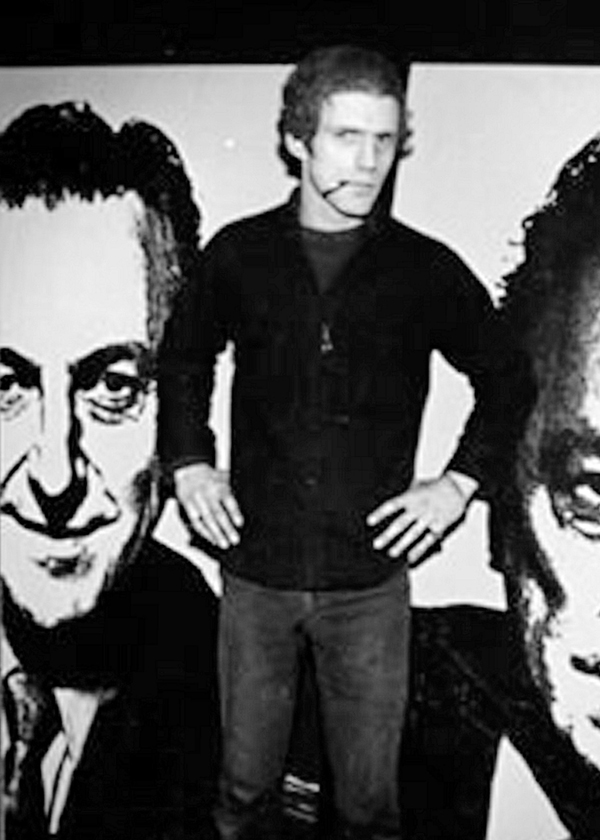

Billy Name with portraits of art dealer and collector Sydney Janis.

Ultra Violet: Andy, when he was much younger, wanted to be a tap dancer. And to be a tap dancer you’ve got to levitate, and Andy could not levitate. So he said, “Gee, I am going to go into art.” Because there’s no criteria in art. Anything goes.*

Andy Warhol: Gee, I wish I could sing, or hum. I can’t even whistle.

* * *

Ultra Violet: Today as an artist I rack my violet brain to find out what shall I be doing, because it’s so transient. It’s going to last five minutes, or fifteen, if I’m lucky. When I met Warhol he said, “Oh, we have to change your name, nobody could spell it.” And I remember reading an article in Scientific American on light—I saw that word ‘Ultraviolet,’ and though it intriguing. I told him, “My name is Ultra Violet,” and he just laughed. It proved to be a good name. I would have never done all those things if I had not met Warhol, and he had not said “Let’s do a film and change your name.” I went into this violet era where everything was violet, from my underwear to my teeth. I am Ultra Violet, still here. I am the only survivor of the Silver Factory.

* * *

Ultra is gone now, but the rest of the Factory survivors still think outside the box: Billy, Mary, Gerard, Ivy, Allen, Robert, Paul, Jane, John, Jonas (who turned 92 on Christmas Eve), Danny, David, Susan, Brigid, Holly, Viva, whose gifted daughter Gaby Hoffman is a successful actress, and Bibbe, whose beautiful and gracious son Beck won the Grammy for Album of the Year in 2015, for the exquisite ‘Morning Phase.’ And Vincent Fremont, founder of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Arts, can be proud that the Foundation has recently finished a record-breaking program of guilt-free donations to universities and institutions (52,786 Warhol works!) … So, Taylor Mead might not be “buried alive” after all. We filmed his hilarious show in a Bowery bar, and wound up using it over end titles. By now you’re thinking, ‘Andy Warhol’s Factory People’ should have been subtitled ‘How Not To Make A Documentary.’ That’s okay; Taylor said he loved us, or was it the scotch? …

Taylor Mead: Andy made them all famous, semi-famous. I am one of the most semi-famous people in the world, except for Ultra of course. But if I’d been rich and famous, I would have had AIDS by now. I would have bought every hustler in Hollywood. I had all the numbers.

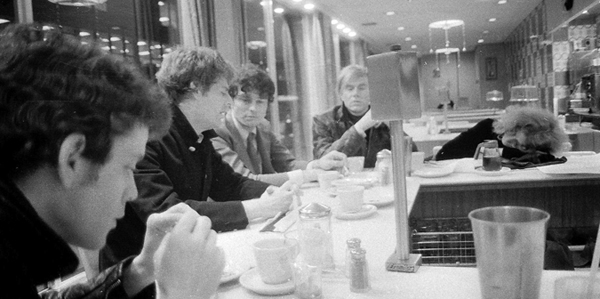

Lou Reed, Paul Morrissey, a friend, and Andy, enjoying the end of a late night, and ignoring, at right, a sleeping Viva.

Viva wakes up in a nearly deserted diner (Paul in B.G.), as Billy Name channels Edward Hopper’s ‘Nighthawks.’

… Taylor checked his watch with a touch of consternation. “Now see, I’m way past my time, actually. They’re waiting for me to go onstage. I have to prepare for my public. I have to appear for the three people that showed up.” Well, he’d forgotten to reset his watch for the fall time change, and was an hour early. More people showed up soon enough, including a couple of curators from the Whitney Museum who were preparing a retrospective of Taylor’s many films. He claims to be “buried alive in museums,” but his fans still turn out. In some marvelous strange way, Taylor sums up the spirit of Lenny Bruce, the advent of the sixties, and the decadal mayhem on the horizon. We had come full circle. And now it was time for … Taylor’s Show!

* * *

Taylor Mead: Okay. In honor of French Television, or people in Paris, or whoever is here tonight—you got the cameras rolling? … I would like to do an homage to the Statue of Liberty, which France gave to us, reluctantly. Or we were reluctant to pay for the trip over—misers on both sides. Finally, it got erected. So my poem is: ‘Is Lesbianism Something New’?” God, I’m slurring like crazy, fucking whiskey and drugs … Is lesbianism something new. Well, there has been a very masculine woman carrying a torch for someone, standing conspicuously in New York harbor for over a hundred years. Here’s to Lady Liberty. Boy, is she tough looking, too …

* * *

Taylor pulled out a ragged paperback and read us his first poem from his first book, for which he was “nearly arrested.” I’d reprint it here, but he deserves to sell a few, even posthumously. After the reading, he took a break to play his radio and sip his ‘prop’ glass of scotch while our titles continued. Okay, they did go on for a while. This tends to happen when you’ve gone over budget and are now begging for money from assorted sources, who expect a plug in the credits, even though we know those credits on TV zip by as quickly as transvestite ripping off five o’clock shadow. Luckily, Taylor, as usual, went on and on …

* * *

Taylor Mead: Here’s another fairy tale by Taylor fucking Mead: Once upon a time, but there’s no such thing as once upon a time. (Taylor holds up his sketch pad). In a large castle—with, like most castles and cathedrals, penises all over the place while outlawing them— In a castle, a monster dwelled. Andy Warhol. Though I think Andy is paying for this reading, so I better be careful. Wonderful Andy. Wonderful Andy was a monster. (flips a page) Can anybody see this? Is it too anemic? I’ll color it for next week. These are the credits … It’s not like the Harry Potter credits, which go on for twenty minutes. Was the movie that good? Loved the dragons.

King Andy shares his silver castle with Ruby.

Young child (to Warhol)

Would you like to add something to that?

Andy Warhol

No.

* * *

And neither would we, except to add a sincere footnote of gratitude to all our Factory People, even the difficult ones (You know who you are), to the patient folks whose footage we licensed, even the difficult ones (You know who you are), and to our workaholic editors and technical experts (You’re all difficult). Thank you Victor Bockris, for writing the best biography I ever read about Warhol. Though I expect there will be more, I don’t expect to read them. Thanks Edie and Nico, for the memories. Thank you to the late Lou Reed and to Bob Dylan, for being good sports and for being more relevant than ever. The big subjects of the sixties are back with a vengeance, and that’s why everybody remembers, even the ones who weren’t there.

So, thank you to former WCBS TV news correspondent and present novelist Mary Pangalos Manilla, and to former filmmaker and present day columnist Diana Colson, who were there in the sixties, and remembered it all differently.

* * *

A final shower of Buddhist blessings on Billy Name for his iconic photographs, his benevolent friendship, his stories, and his unique insight … Billy did not see his trunk, which held all those negatives (and Valerie Solanas’ script) until 1987. When Andy Warhol died on February 22 of that year (Billy’s birthday!), the trunk was returned to him … Sadly, those negatives were ‘lost’ to the ages once again, thanks to an erstwhile agent, but that is another tale for the N.Y. Times, and luckily we had already made ‘heavies’ of most of them to meet television broadcast standards.

Warhol, too, had his work “stolen left and right.” Ever Zen, he just shrugged his shoulders, like Billy, and expected matters to eventually resolve themselves (with a platoon of busy lawyers). However, he did once complain that “The Campbell’s Soup Company has not sent me a single can of soup.” … So thanks again, Andy, ironic until the end, for a truly Warholian experience. By the time I had gone through my piles of research and newspaper clippings, I came to the same conclusion as your multitude of fans and foes: You reached the public as no other artist has before you, except maybe Picasso, which has made you the most collected (and protected) artist on the planet. Therefore, rather than encourage any more legal attention from the keepers of your eternal flame, we have wisely decided not to do the sequel.

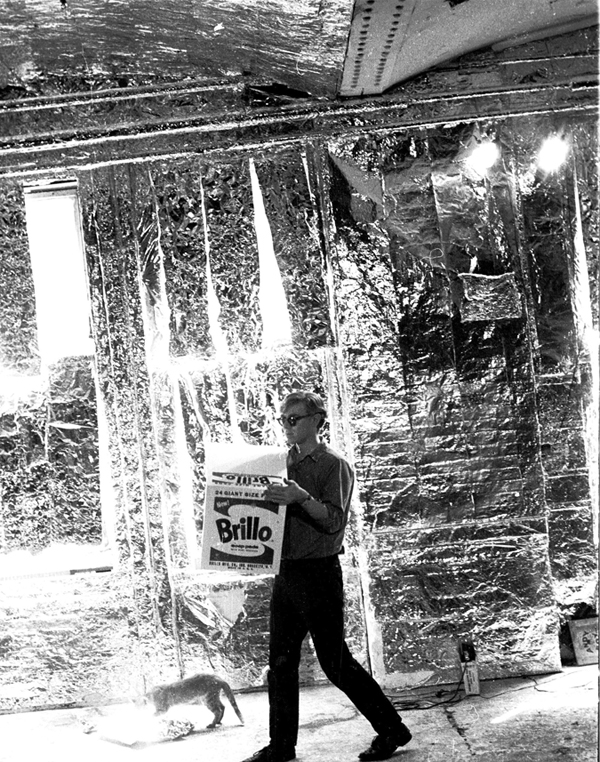

Billy photographs Andy’s art as it leaves the Silver Factory.

* Actually, there were a couple of blacks (of course, beautiful) in Warhol’s coterie, dancer Rufus Collins (of ‘Couch’ fame) being one. Finkelstein photographed the striking Donyale Luna, a willowy model I once knew, who worked in a few Warhol movies, including ‘Camp’ in 1965 with a cast that included Baby Jane Holzer, Jack Smith, Mario Montez and Gerard Malanga. Luna’s own ‘Donyale Luna’ debuted in 1967. She succumbed to an overdose at 39 … Another unconventional beauty, who prided herself on being “a self-made” woman, Candy Darling succeeded in attaining true Warholian superstardom. She lost the battle with leukemia at 29, but achieved underground immortality. A film of her life, ‘Beautiful Darling,’ came out in 2011. Heartbreaking … Nobody made a movie about poor old ‘Nat the Hat’ when he died in 2009 of emphysema (though there were some sighs of relief). He left a legacy of provocative pictures, a peon to the sixties. The New York Times gave him a two-page obit, and suddenly all his stories about Warhol had the ring of truth about them …

* Nor could Warhol dance a step, but before the canvases of car crashes and falling bodies came the whimsical life-sized blow-ups of dancing feet in detailed diagram, showing one how to Fox Trot. We choreographed the pictures to the tune of Cole Porter’s classic ‘Anything Goes.’ Mysteriously, the Warhol Foundation did not find it funny. Well, there was a whole lot they didn’t find amusing about our series.