OUT OF MONEY

A lot of those people in the sixties were like bottomless pits as far as money was concerned.

—Victor Bockris

Louis Waldon: When you go to talk business with Andy, he really didn’t want to talk about it. He would say (mimicking), “I can give you some money, but not very much. I can only give you maybe a hundred dollars.” I said, “Great!” I thought that was perfect. You did a movie in two hours; at that time that was good pay. But the actors, especially Brigid and Viva, said, “Don’t accept anything from Andy except money, because money really gets to him, money really makes him nervous.”

Brigid Berlin: Oh I know, people like Viva (mimicking), “He owes me money,” and everybody else, “Oh he never paid me! I mean, I made him famous, it was, you know, all me.”

* * *

We licensed footage of Brigid where she simply sits and complains to the camera, much like Viva, which is why they became such friends. During these gossipy tirades, Warhol would be an occasional presence, entreating Brigid to, “Just say whatever you feel like.” But Brigid felt more comfortable without Warhol in the room. While smoking endless cigarettes, eating chocolates, or sucking down a canister of Reddi Whip, she would confide to a featureless camera. Is this frankly any better than the eye-rolling reality shows of today? Well, no. But Warhol did it first …

* * *

Brigid Berlin: So I made this fantastic tape for Andy, and he said, (mimicking) “Well, we just don’t have any money just now.” How could he not have any money? I mean really …

* * *

According to auction tallies for 2014, Warhol outsold every other artist. Collectors bought 1,295 works totaling $653.2 million, ahead of sales even for Picasso.

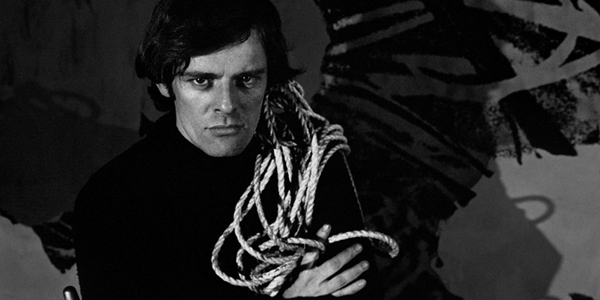

Andy dials for dollars. (Photo: Billy Name)

Taylor Mead: I was determined to get cash from Andy. I lost. In fact, the son of a bitch— Well, I shouldn’t put down his mother; his family are darling. But Andy was as cold as ice. It was sort of a brilliant act. He was a cheap, cheap genius. When he owed me fifty bucks and I’m in Madrid starving to death, he wouldn’t send the money … my father was cheap and rich, and I find that is one of the basic ABCs of the world. If you’re rich and cheap, like the United States, my father, Andy; if you are cheap … “Moooon River.”

* * *

Taylor had once again broken into song with ‘Moon River.’ I’m guessing he wanted to say “Kiss my ass, you cheap filmmakers.” It was time to get Mr. Mead, former Beat and unredeemed downtown reprobate, another drink.

* * *

Billy Name: Taylor Mead was already an established underground film star, but when he started working with Andy he would be a little snippy sometimes, like, “Gee, where’s all the money?” or “Warhol is so cheap and tight.”

David Croland: He wasn’t stingy at all. Andy was always giving money to everyone, left and right. He gave everyone money, every one of the Superstars, their girlfriends and their boyfriends. Thirty people a day. I could name fifteen off the top of my head I think he gave money to, including Susan (Bottomly) and myself.

Jonas Mekas: Andy was a very, very, kind person. And everybody felt very, very good in his presence. I disagree with all those accusations that are sometimes thrown at Andy. There were misunderstandings like, “Oh, he just went up to, he sucked up to the rich people.” No, they came to him. He did not go after them. They all came. I know, I’d been around then. They just flocked to him, searched him out. They did because of that openness, because Andy did not reject anybody.

Nat Finkelstein: It was all a facade. I think the key point here, and bringing it up in a very nice way, is to say that Andy created this place to work, and as a social environment it could do more for him. In doing that, he incited a lot of people to get excited about working with him, and be part of it. You can always manipulate somebody by lying. But shaking hands on a deal and turning your back on it is something else. I suggested and wrote the outline for ‘The Andy Warhol Index.’ He and I came to a handshake agreement about a 50-50 split. I did the proposals. Black Star, my agent, put him under contract, and I sold the book to Chris Cerf up at Random House. All of a sudden, Andy appears with a whole bunch of high-powered lawyers behind him. So, as far as the free living, blah blah—that was crap, man … that was Andy manipulating an aura for himself. It was all about promotion, and Andy would sell himself to just about anything. Once he drove around in this truck. On the side of it was ‘Dannon Yogurt.’ He sold himself for a year’s supply of yogurt.

Vincent Fremont: He really revolutionized and turned the ‘cultural’ world upside down. He is synonymous with American and International culture. With the help of the press, he built a myth, because they believed everything he said. They neglected to understand his sense of irony, his sense of humor. They took everything verbatim. So he played them. It got him in trouble sometimes. He said, at one point, ’68ish, that Brigid Berlin did all his paintings—which was very clearly not true. But people got freaked out when they heard that. They (journalists) started reading each other’s articles and pretty soon that myth starts up, based on no fact.

* * *

Of all the myths that sprung up around Warhol like magical beanstalks, perhaps the most enduring and egregious was his perception as a demonic ‘Pied Piper’ for rudderless children, and the furor was to reach fever pitch. As members of his disenchanted troupe began to drop by the wayside, Greenwich Village elders, far less benevolent than their sage-smudging West coast counterparts, were readying the acetylene torches. As Mary Woronov would say: “Enough already with Warhol.”

* * *

Mary Woronov: I never went anywhere with Warhol—we just kind of formed a line and followed him. When they started setting things up for me, like in a bedroom with this fat man, “Okay Mary, get on the bed with him.” I said, “No.” I would not be pushed around like that or set up. But Ronnie Tavel wrote plays for me, so even Warhol sensed that I was actress to be used. But what happened to me is that I had a fight with Paul Morrissey. He wanted me to sign a release. I said, “I don’t have to sign unless you want to pay me. And I know you don’t, so I’m not signing.” Warhol was very, very angry and I stopped going to the Factory. My mom got on the phone. “My daughter didn’t sign the release. Would you like to go to court or would you like to settle it?” So he settled and gave me money. Hey, I’m not going to be squashed like that. So, enough already with Warhol. I’d done enough with him. It was a good thing to leave him. I mean, you can’t stay there forever.

Victor Bockris: Mary’s mother sued Andy after she appeared in ‘Chelsea Girls,’ because she was underage. Not for that, but to get paid for her role. She got a thousand dollars, and Andy subsequently had to pay everybody who acted in the movie a thousand dollars, so (laugh) he wasn’t too happy.

Andy enjoys a rare moment of solitude. (Photo: Billy Name)

Andy and Family, including Gerard with model Donyale Luna and Ingrid Superstar, Danny Williams, Cathy Starfucker, Paul Morrissey. Handsome Kip ‘Bima’ Stagg (foreground) starred with Edie Sedgwick in ‘Beauty 1,’ then married my cousin Deirdre. (Photo: Nat Finkelstein)

Jonas Mekas: Paul Morrissey became very, very powerful. So it was a combination after ‘Chelsea Girls,’ not just pure Andy. Like some movie companies, a certain production style is imposed upon the films—this is MGM, this is Warner Brothers. So that was the end of Andy’s cinema, in a way, because at that point Paul Morrissey wanted complete control, and he used a lot of the same stars. Later Morrissey went on his own, and those films, ‘Trash,’ ‘Heat,’ ‘Flesh,’ cannot be called Andy Warhol films. One could say they were produced by Warhol, but those were Paul Morrissey films and they have his stamp on them.

Paul Morrissey: I don’t remember ever saying anything to Andy where he didn’t say it was a good idea. He was so glad to have any ideas, because Andy was not the kind of person, who had ideas. He never directed anybody; he didn’t interfere with anybody, because he didn’t know what to interfere with!

Ivy Nicholson: I can’t stand Paul. He was doing really bad business. He would always say, “Oh, Andy’s gay.” Which of course he wasn’t—Andy was bi-sexual. He’d promised people if the movie ‘I, A Man’ was a success they’d all get paid much better money. Andy got the idea from a Swedish movie called ‘I, A Woman.’ And ‘I, A Man’ was about a man who goes out with a lot of women and has affairs with all them, all totally different. The movie had a more evolved script than usual. The photography was better, the sound was better. So ‘I, A Man’ was a huge success. And we are not getting any more money. Why not? If ever I get money I am going to sue him.

Billy Name: It’s the same old story. If you were not there to do the work, and the groundwork to make and build something you have no idea what it costs to produce what happens. So people came in and said, “Oh wow, Warhol can make me! And he is supposed to pay me isn’t he?”

Louis Waldon: Right. What they didn’t understand is, Andy had a big Factory. He paid the rent on it. You could go there and hang out all day if you were liked. And hang out while he was working. They had like a little club. They had a lot of fun. Andy would produce the movies. They cost $1500 to $2000 at that time to produce an hour, two hour film in color, with sound. So, he paid for all that. I went because of the immediate publicity. The notoriety was great. Here you were on the cover of magazines and newspapers. Your name is mentioned all the time. It was a good move for an actor like me, who was working with off-Broadway, which was a hundred years behind the times.

Kip ‘Bima’ Stagg: I was instantly part of Andy’s inner circle, the ‘pretty boy.’ It was fun being part of the hottest scene in NYC. But it was soon clear that apart from Andy’s paintings, there was no creativity going on except for acting ‘fabulous’ and ‘outrageous.’ There was as much substance to Andy’s Superstars as all those shiny silver Mylar balloons floating on the ceiling.

* * *

As wiser heads left the scene, a fresh crop of street kids arrived, thrilled to be part of the Warhol sideshow. As before, some came from wealth and ennui, others were runaways, eager for adventure. Among those replenishing Warhol’s disgruntled, dwindling troupe were Geraldine Smith and her vivacious friends Patti D’Arbanville and Andrea Feldman, future Warhol stars, of which more about in the upcoming chapter devoted to Max’s Kansas City, which would become the Factory commissary.

* * *

Geraldine Smith: When I ran away. I was about fourteen, running down the street in the Village. I had on these skin-tight clothes and hair down to there, all this black eye make-up. A couple of guys invited me to a party, and I went with them to the Warwick Hotel. It was for the Beatles, and we hung out with them all night, smoked pot, and ate steaks at Max’s Kansas City. That’s where I met Andy. I went in with my friend Andrea. She wrapped a towel around her head like a turban and went up to Andy and said, “I’m Mrs. Warhola.” And that was it. Everybody was there, and we kept going back every night because it was one great party. Paul was doing ‘Flesh’ and asked me to be in it. I’d say yes to anything. I’m on an adventure.

Allen Midgette: Max’s Kansas City, I go in there that night, I see Paul Morrissey. He’s sitting in a booth. And he says, “Oh, would you like to have a drink?” Well, Paul never asks me to have a drink, okay? (mimicking) “Would you like to go to Rochester in the morning and pretend to be Andy?” So, now I’m going to do a college lecture for Andy for free? That’s what I expect, I mean that’s what I had learned to expect. So, he said, “Well, you get six hundred dollars.” “Oh, that’s fine. When do we leave?”

* * *

The luckless Allen Midgette, always the brunt of the hip Factory’s hippie prejudice, had recently returned from San Francisco. He tended to leave New York for calming Zen periods, only to come back for yet another surrealistic filming experience with the Warhol Family. After a while, fed up with their “aggressive amphetamine-fed histrionics,” Allen would take off again. While he worked on the films, Allen often bunked in with his good friend and fellow mellow actor Louis Waldon, who lived in the Meat Market district. Whenever he arrived in New York, Allen, like all the others, was usually broke. And there was Warhol, waiting with open arms, with offers of imminent stardom, but don’t expect SAG minimum. At least Paul paid him.

According to those who worked on Warhol films, Paul Morrissey really taught Andy the ropes. (Photo: Nat Finkelstein)

“Like a little club.” Louis Waldon, Nico, and some sad flowers share a few beers at Max’s Kansas City, the favored Factory hangout. (Photo: Billy Name)