When We Were Young

As a little girl, the Queen was taken by her grandmother, the late Queen Mary, to a concert. Observing her wriggling after the interval, Queen Mary suggested that she might like to go home. ‘Oh, no, Granny, just think of all those people waiting to see me outside.’ The little princess was immediately removed through a rear exit.

The Archbishop of Canterbury once ruffled the 7-year-old Princess Elizabeth’s hair and said, ‘How is the little lady?’ The Princess replied, ‘I’m not a little lady, I’m a Princess.’ Queen Mary intervened. ‘You were born a Princess. I hope one day that you will be a lady.’

When the Queen was young, her governess, driven to distraction by her pert charge, decided that she would not be on speaking terms. Whenever Princess Elizabeth addressed her, she did not reply. After this had been going on for some time, the Princess said, ‘But you can’t do this. It’s Royalty speaking.’

In an attempt to give them a flavour of normal life, Miss Crawford, the nanny, used to take Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret on various outings around London. But when they went to tea at the Young Women’s Christian Association in Great Russell Street, they got rather more normality than they’d bargained for. Princess Elizabeth was unable to grasp the rudiments of self-service and left her teapot on the counter. She got an earful from the tea lady.

At Windsor during the war girls in the same Girl Guide troop as Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret noticed the frequency with which they played that memory game where you get a glimpse of a trayful of items and then, when it has been whisked away, you have to recall as many of them as you can. Some even went so far as to complain. Then it was explained that it was all for the sake of the Princesses: a good memory would be vital in their Royal lives and this was a sure way to achieve one.

Aged sixteen, Princess Elizabeth approached her duties with all the dangerous enthusiasm of the young. In 1942, after inspecting troops, she reported some soldiers for having dirty engines and they were put on a charge. Later this thorough approach was dropped.

In Kenya, just before she became Queen, Princess Elizabeth was in a fix. Walking through the bush, her car half a mile away and the ladder to her tree house still fifty yards ahead, she found herself in dangerous proximity to a herd of furious elephants. But she forged on regardless.

Cynthia Gladwyn, ambassadress to Paris in the early 1950s, had taken a great deal of trouble to find young people, at the last minute, to amuse Princess Margaret during her stay at the embassy. But on the Sunday morning, Princess Margaret was laying claim to a cough, although, the ambassadress couldn’t help noticing, it did seem to be oddly intermittent. Nevertheless she couldn’t possibly go out and Cynthia Gladwyn was left to visit all the disappointed people without her. Imagine her astonishment, on her return, to find Princess Margaret equipped with a magnificent new coiffure. It was the ambassadress’s own maid who revealed the truth. The celebrated hairdresser, Alexandre, had visited the embassy while she was out. This had, in fact, been the plan all along. The next day, after enduring another evening of Princess Margaret’s on and off coughing, Cynthia Gladwyn couldn’t restrain herself from saying, ‘I do hope having your hair shampooed didn’t make your cough worse.’

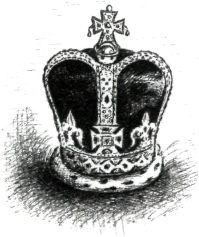

When she first came to the throne the Queen was very reluctant to put on any part of the Crown jewels – she would not contemplate even one of the massive diamond necklaces or pairs of earrings. Eventually, to pass a dull afternoon and because the evil day could not be put off for ever, she agreed to have the whole collection brought round from the Tower of London. First she tried on the dainty single rows of diamonds, and slowly built up to the more weighty pieces. At last, decked out in the Imperial State Crown, a huge lumpy necklace, earrings like diamond scythes and the coronation amulets, she dared to look in the mirror. There was a prolonged silence. At last she said, ‘Golly’.