JOSEPH DUVEEN: THE SALESMAN AS ARTIST

The years leading up to the First World War are remarkable as a period of uniquely intense innovation and revolution in modern art. Pioneering dealers played an extraordinary part in fomenting this revolution. Without men such as Vollard, Kahnweiler, Cassirer and Herwarth Walden the course of Modernism would have run very differently. Their crucial contribution is examined in later chapters. But their commercial activities represent a tiny proportion of the value of the art traded at this time. The removal of the import tax on works of art into the US in 1909 led to prodigious old master traffic in the years that followed. The dealer-princes with outlets in the USA, the Duveens, the Knoedlers, the Wildensteins and the Seligmanns, were turning over huge sums: Duveen’s sales in Paris totalled $13.5 million in 1913 alone. And the good times continued to roll after the war, too. Such was the wealth that the Duveens and the Wildensteins had accumulated that even the Wall Street Crash in 1929, so disastrous to many of their clients, only briefly disturbed the momentum of their success.

In 1936 Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery in London, visited the palatial New York galleries of Joseph Duveen in the pomp of the great dealer. Clark takes up the story as the proprietor himself, recently created Lord Duveen of Millbank, showed him round:

We were accompanied in our peregrination by a heavily-built man called Bert Boggis, who had worked in the packing department and had all the qualifications of a chucker out. Since he had long accompanied Lord Duveen as a personal guard he had come to know the names of painters, which is more than Lord Duveen ever did. ‘There you are,’ Duveen would say as we entered the room, ‘it’s a Blado – what is it Bert?’

‘Baldovinetti.’

‘That’s right, Bladonetti. What do you think of it?’

‘Well, I’m afraid it’s a bit restored.’ (It was in fact a completely repainted work of a painter called the pseudo-Pier Francesco Fiorentino.)

‘Restored? Ridiculous. Bert, has it been restored?’ Silence. ‘Ah! he knows. Next, next.’ A profile head appeared. ‘It’s a Polly, Polly – what is it, Bert?’

‘Pollajuolo.’ Silence all round.

If the picture exhibited was one of his favourites, Lord Duveen would blow kisses at it. Occasionally his enthusiasm would make him giddy with excitement. Then Bert would say ‘Sit down, Joe, keep calm,’ and the great man would passively comply.

Duveen was an epic character, whose biography by S.N. Behrman is one of the funniest books ever written about art. A salesman of genius overburdened neither with scruples nor with knowledge of academic art history, Duveen was born in London in 1869, which meant that he was approaching his prime at the turn of the century. This was happy timing: around 1900 there was a perfect confluence of socio-economic developments in America and Europe ideal for an international art dealer of energy and initiative to exploit. On the one side of the Atlantic there existed a bevy of increasingly rich Americans who had everything except class and history, and on the other a slew of European aristocrats, torpid with class and history but in increasing need of money. How to remedy the situation? What could be satisfactorily transferred between them that would endow class and history to the former? Art, in which ‘old’ Europe was rich, was the perfect commodity. It was this transference that Duveen perfected, taking up comfortable residence in that sweet territory positioned between the lower price of the thing sourced and the higher price of the thing placed. It was a territory that he generously shared with a number of others: experts, like Bernard Berenson and the German museum director Wilhelm von Bode, whom he paid generously; venal middlemen, often shameless aristocrats claiming secret commissions; and restorers, to whom Duveen gave every encouragement to express themselves creatively.

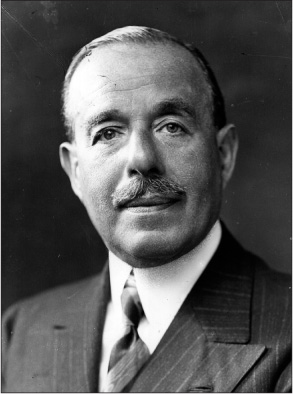

Joseph Duveen: ‘when he was present everyone behaved as if they had had a couple of drinks’.

The statistics are extraordinary: almost 50 per cent of the legendary Andrew Mellon collection, which provided the basis for the National Gallery in Washington, was supplied by Duveen. Indeed Duveen is calculated to have been responsible for the import into American collections of 75 per cent of their best Italian pictures. In this respect he invented a kind of cultural money laundering: by taking the rich Americans’ new money in return for classic European art, he was transmuting that new money into old. And the old money, in the hands of the European aristocrats, was running short. From the 1880s onwards even the British aristocracy, hitherto largely buyers of art rather than sellers, found themselves under financial pressure, as a result of the collapse of agricultural prices under the glut created by the expansion of farming in the new world. Land rich and cash poor, they looked around for what they could sell, and their ancestral art collections were the easy options.

Joseph Duveen – Joe – was born into an established art-dealing business. The Duveen firm created by Joe’s father and uncle was already by the beginning of the twentieth century an important and well-connected one, with branches on both sides of the Atlantic. For his coronation in Westminster Abbey Edward VII called in Duveen Brothers as decorators to improve the look of Buckingham Palace and brighten up the ceremony at the Abbey. But the young Joe was very keen to enter the picture market, and in June 1901 he persuaded his father to pay 14,050 guineas for a late-eighteenth-century portrait by Hoppner, an auction record for any English picture. As a statement of intent it was impressive. And it reflected a simple equation that Joe formulated early on: that a high price was a mark of quality, and a low price a mark of the lack of it.

In the five years either side of 1900, business at Duveens tripled. The Duveens had initially operated out of shops. Now they moved up a level of grandeur, and their premises in London, Paris and New York began looking like opulent private houses. Joe’s picture business flourished. Besides English portraiture, he purveyed French eighteenth-century masters, Dutch works as long as they were by Rembrandt or Hals, and of course classic Italian works of the Renaissance. This, as defined by Joe, was rich American taste. And for the first four decades of the twentieth century rich Americans were very happy to buy into it. Later-nineteenth-century and modern art he disapproved of because there was too much of it. He also disapproved of auctions, where prices were too fortuitous and constantly needed help. In the words of his long-time business colleague Edward Fowles, Joe was dynamic, enthusiastic, excitable, aggressive and impatient. He had a good working knowledge of the British school, a superficial knowledge of French and Dutch painting, but very little of Italian. The shortcomings of his connoisseurship were usually disguised by his consummate salesmanship, but with Italian paintings he was intelligent enough to realise that he needed expert help. It came in the greedy, high-minded, unscrupulous and thoroughly conflicted shape of Bernard Berenson. The partnership that they formed of salesman and scholar was one of the most productive in art-dealing history, but also – on Berenson’s side at least – one of the most fraught.

Berenson’s emergence as the expert with whom the art trade must reckon in their dealings in Italian Renaissance art was underlined in 1895, at the Italian Art Exhibition of that year. The young scholar from Boston produced an ‘alternative’ catalogue to the show, pointing out all the misattributions and worse. In fact he was already working with Otto Gutekunst of Colnaghi in supplying Isabella Stewart Gardner with major Renaissance art. This eccentric but highly driven collector, also from Boston, was buying heavily, and provided Berenson with an early lesson in the pitfalls of trading in art. He sold her three Rembrandts at rather larger mark-ups than he admitted. He only just avoided being found out by her suspicious husband. It was a nasty moment, a glimpse of the moral chasm opened up by the dangerous elasticity that art offers between the price of the work sourced and the price of the art placed. This is indeed the sweet spot for dealers, but it can very rapidly become the bitter spot if your client gets wind of the extent of the gap. Not for the last time in his life, Berenson seemed to want to have it both ways, which elicited a justified rebuke from Gutekunst. ‘Business is not always nice,’ he wrote to Berenson, continuing:

I am the last man to blame you, a literary man, for disliking it. But you want to make money like ourselves so you must do like wise as we do… if the pictures you put up to us do not suit Mrs G it does not matter. We will buy them all the same with you or by giving you an interest in them… It is important for both of us to make hay while Mrs G shines.

Berenson and his wife Mary became expert at smuggling pictures out of Italy to sell to Americans. ‘I don’t consider this wrong,’ wrote Mary in 1899, ‘because here in Italy the pictures are apt to go to ruin from carelessness.’ The Berenson method was to approach the overseer of the local gallery in Italy to get permission to export. They presented the work in a box, but substituted a worthless daub. The box was then given a seal by the overseer, but could be reopened elsewhere and the real picture replaced for the actual act of export. Other times, other standards.

The existence of Berenson made Duveen nervous and excited at the same time. Duveen recognised that, whereas English eighteenth-century paintings generally had clear provenances, and Dutch and Flemish art presented fewer problems of expertise, Italian Renaissance art was the most speculative market of all. There were huge profits to be made in it. And Berenson, as the acknowledged expert in the field, was an asset almost beyond price. He could provide the expertise that would turn the speculative picture into the moneymaking certainty. His was the eye that could authoritatively attribute the works to individual artists, some of whom he had discovered, and others of whom he had invented.

But Berenson also needed Duveen, because he needed money. He had been born with none, and his precocious brilliance with works of art had propelled him into circles where there was a lot of it, often a dangerous sequence of events for art experts. In particular his dream for I Tatti, the villa he had set his heart on in the Tuscan hills, which needed very expensive financing. So they signed a contract in 1906. If Joe had been a self-analytical man he might have recognised in Berenson the attributes they shared: egotism, ambition, pleasure in a rich lifestyle, greed and charm. But it was left to Joe’s uncle Henry, usually a force of reason in the Duveen business, to note perceptively of Berenson: ‘It appears that he could be most useful to us, but I advise caution as all are agreed that he will never play the second fiddle but must lead the band, if not conduct it. It could be dangerous to be out of step with him.’

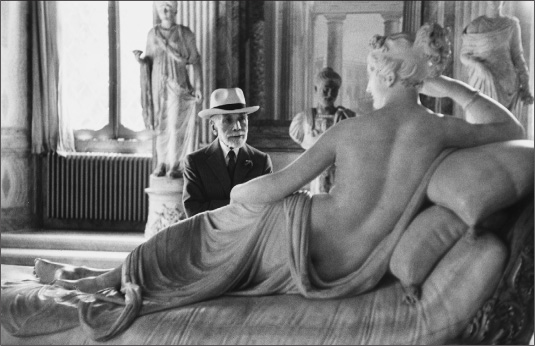

Bernard Berenson, reaffirming his belief in tactile values.

Thanks to Duveen, Berenson started making large amounts of money. It has been calculated that he earned more than $8m in the twenty-six years between 1911 and 1937; enough to buy and improve I Tatti, institute a 16-acre formal garden, acquire a car commensurate with his new status and engage a butler, an employee that Roger Fry wryly described as ‘that essential adjunct to academic life’. Within Duveen’s organisation high levels of secrecy were maintained to protect Berenson. The transactions on which he was due commission were entered into ‘the X book’, a confidential ledger to which only Duveen and his right-hand man Fowles were privy. Tellingly, Berenson’s codename within Duveen was ‘Doris’. Those familiar with Ancient Greek will recognise that the name shares a root with the word meaning ‘bribe’.

Did Berenson act fraudulently in the expertises that he made for Duveen? It is certainly true that his attributions became more generous in his years of cooperation with the art trade. And there is also no doubt that Berenson came to hate himself for the Faustian pact he had entered into, for the compromise of his scholarship that it represented. Posing as an impartial judge – an art historian and a connoisseur – when in reality you are a paid advocate is on the edge of dishonesty; hiding and covertly expanding your commission is straying further towards the territory of fraud. ‘I soon observed that I ranked with fortune-tellers, chiromancists, astrologers, and not even with the self-deluded of these, but rather with the deliberate charlatans,’ reflected Berenson bitterly, and a trifle disingenuously, on his role in the art market. Elsewhere he spoke of Duveen’s seductive powers: ‘that noble peer’s power of persuading without convincing’. But Berenson himself was also guilty of overenthusiasm, and the floridity of his language in his praising of pictures turned into a useful sales pitch for Duveen.

There are specific instances when, if Berenson does not transgress a moral line, he strays very close to it. In 1922 Duveen had to get retrospective certificates from Berenson for a collection of pictures which he had sold to the financier William Salomon. Nicky Mariano, the companion and confidante of Berenson in his latter years, says Berenson refused categorically to do this; but nonetheless they appear in the X book. And of course everything that went in the X book entitled Berenson to a financial reward. In the back of Berenson’s mind turned the constant mathematics: a more positive attribution = a higher price from the buyer = a higher commission (anything from 10 to 25 per cent of the selling price) payable to Bernard Berenson. Another ambiguity was the Venetian portrait of Ariosto: in 1913, when Duveen was selling it to Benjamin Altman, the department store tycoon, Berenson was prepared to ‘stake his reputation on the painting’s being a Giorgione’, undaunted by the fact that in 1896 he had declared it as ‘a work by the young Titian, or a copy of such a work’. It was a convenient change of mind.

Perhaps it is kinder to say that, as the supply of Italian Renaissance masterpieces dwindled, Berenson – under pressure from Duveen – succumbed to bursts of attributional optimism that tended to give the benefit of the doubt to a number of pictures that did not always deserve it. As Meryle Secrest suggests, one of the reasons for his inaccuracies is that from the 1920s onwards he was invariably judging from photos. Perhaps this was deliberate. ‘Given Berenson’s prickly conscience and his perfectionist expectations for himself, traits so evident in his later diaries, perhaps the only way he could live with himself, in the thick of a very murky and conniving world, was to judge from evidence that, after all, told him so little. He could always blame the evidence.’

Berenson was a demanding financial partner. He wanted maximum benefit from the deals he facilitated, but no responsibility for the actual making of sales. This meant that he participated in profits, but not in losses. He was very firm on this point. It was as if the Catholic Church secretly owned a condom factory, the profits of which they were happy to bank, but when a faulty batch of merchandise was returned to the maker, they were not willing to accept the loss. A moral balancing act had to be achieved by those experts who provided authentication services to the art trade (Berenson, if the best known and the most brilliant, was not the only one). Some, like Wilhelm von Bode, salved their consciences by using ambiguous language. ‘I have never seen a Petrus Christus like it,’ he wrote once, seized on by the dealer as the ultimate accolade of praise for his picture, but actually signifying the expert’s doubt as to its authenticity. Bode, in his old age notoriously susceptible to the charms of young women, found Berlin dealers sending their most attractive secretaries round to him in order to get positive verdicts on works from their stock. He obliged regularly. René Gimpel, as ever, is an amused witness of the process: he records how the eminent art historian and museum director Max Friedländer was passionately attracted to a dealer’s wife, who squeezed authentications out of him by hints of the surrender of her virtue. ‘If she slept with him,’ notes Gimpel, ‘it would be swiftly finished, so she keeps her garters fastened. On the basis of such certificates, American collections are formed!’

Duveen’s ability to make people do what he wanted was legendary. He fought battles on many fronts simultaneously, deploying an extraordinary armoury of allies in order to win his victories. Clients, staff, tamed experts, restorers, fellow dealers, lawyers, aristocratic middlemen, even royalty were all persuaded by a variety of means into doing his will. His success was based on huge energy, a relentless optimism, and a kind of blustering charm that the British found rather marvellous because they thought it was American and the Americans found rather marvellous because they thought it was British. ‘Joseph Duveen does business as he would wage war, tyrannically,’ recorded Gimpel in his diary in September 1920. ‘He is an audacious buyer and an irresistible salesman. But he is childish too, and indeed asks me like a child what people think of him and his firm. “That you are a great seller and that you have the most beautiful pieces.” “They’re right, don’t you think?”’ Even Duveen needed reassurance occasionally.

At the beginning of his career, Joe learned the trade from his father Joel and his wise uncle Henry in New York. And in his prime he was blessed with a supportive and intelligent team of staff. Much of the detail of the buying was actually seen through by his brothers Edward and Ernest in the London gallery and Edward Fowles and Armand Lowengard in Paris. There were times when they saved Joe from himself, because in the art market enthusiasm can occasionally be a dangerous thing. Then there was the redoubtable Bertram Boggis, a character with a name straight out of P.G. Wodehouse, who assumed increasing power in the Duveen entourage. Boggis was recruited from the New York waterfront (where he was working, as legend went, after deserting from an English cargo ship in 1915) in answer to an advertisement for a job as a porter at Duveen’s. There was a queue of applicants. Each time Boggis was rejected, he rejoined the end of the line and presented himself as a different candidate. At the third attempt he was taken on, and became the commissionaire, a role in which he felt it necessary to carry a pistol. He had a face like a bullfrog and the sort of street wisdom that made him infinitely resourceful. Prohibition he treated as an opportunity rather than a limitation. He used a fashionable delicatessen on Madison Avenue as his base, from which he conjured illegal liquor for the Duveen clientele.

One of Boggis’s roles was as gatherer of ‘below stairs intelligence’: with generous bribes he routinely recruited servants of Duveen clients to pass on any private information that might be of use to Duveen in his business negotiations with their masters. It was Boggis’s proudest boast that when Andrew Mellon was Secretary of the Treasury ‘the contents of his waste-paper basket were on the train from Washington to New York within an hour of his leaving his office in the evening’. In Paris in the 1920s information obtained by similar means established Maurice de Rothschild’s problems with constipation. As already mentioned, the telephone call to his valet de chambre to see if his bowels had moved that morning determined whether the day was propitious for offering him a masterpiece. The strategy of winning over a client’s household staff still goes on. Not so long ago a leading dealer, discovering that a major collector’s butler was a keen amateur artist, offered the butler a West End exhibition in order to curry favour with his master. Indeed the butler of another Duveen client, Jules Bache, was so well looked after by Boggis that he managed to send his son to Harrow.

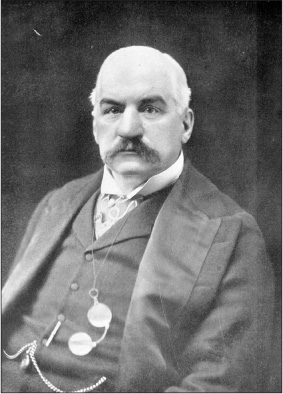

The art market was stupendous in the period leading up to the First World War. The confidence of the leading players verged on the hubristic. In 1909 the Duveens’ rival Jacques Seligmann bought the sumptuous Palais de Sagan in Paris as his centre of European operation. Here he entertained and sold to his American millionaire clients on their visits to France. It was not just pictures, of course: Seligmann was offering the full works, including furniture, silver, tapestries, faience, gold boxes. The descriptions given by Germain Seligman (he dropped the second ‘n’ after obtaining US citizenship) of his father’s sessions with the visiting J. Pierpont Morgan in the Palais de Sagan are vivid accounts of the relationship that existed between these rich collectors and their dealers. In the course of an afternoon’s exchange of commercial negotiation and aesthetic exposition half a million dollars’ worth of business might well have been done. ‘Great transactions must be accomplished with lightning and thunder,’ comments Germain Seligman. ‘Otherwise where is the fun?’ In 1914 Jacques Seligmann bought the Wallace-Bagatelle collection ‘sight unseen’ for an initial investment of $500,000. It was a huge gamble, but Seligmann knew it had been assembled by the great Lord Hertford, and once Seligmann got to see it in the house at 2 rue Laffitte, it turned out to be on a par with what is now the Wallace Collection. In the summer that remained before war broke out, Seligmann moved everything to the Palais de Sagan and managed to sell many treasures from it to Frick and other international collectors.

The early twentieth century was also a golden age for American plutocracy. Of what sort were the men who had made prodigious amounts of money, and thereby qualified as the natural clients of Duveen and the other art merchant-princes? In their behaviour and aspirations the very rich are largely unchanging over the years. But one thing distinguishes these early tycoons: they were often not very prepossessing to look at. Perhaps the biggest difference between the rich of today and those of a hundred years ago is the lengths to which twenty-first-century plutocrats are prepared to go to preserve and beautify themselves (even the males). Botox, plastic surgery, hair tinting and transplants are all copiously employed to correct the malformations of an unkind Nature, to hold back the years, and reinforce the idea that if you are rich enough today you can buy anything, even eternal youth. There was none of that nonsense in America in 1900. Men such as Benjamin Altman, Henry Clay Frick, Pierpont Morgan, P.A.B. Widener and the Huntingtons, Collis and Henry, were rough-hewn moguls, brutish, seeking salvation only in the soft emollient of art. All were self-made men: Altman in department stores, Frick in steel, Morgan in banking, Widener in meat and the Huntingtons in railways. All were conscious of the need to refine themselves, and seduced by the vision of art that Duveen sold them. Art offered atonement, an idea that the artist-turned-adviser Mary Cassatt was eager to play on in the interests of a sale. She bullied her client James Stillman mercilessly. In front of a Velázquez she urged him, ‘Buy this canvas, it’s shameful to be rich like you. Such a purchase will redeem you.’

J. Pierpont Morgan: a stranger to the cosmetic surgeon.

The other notable thing about the very rich of the early twentieth century, according to Behrman, was their taciturnity. ‘Perhaps there is some mysterious relation between the possession of great wealth and parsimony of speech,’ he speculates. Elsewhere he suggests that millionaires talk slowly and sparely ‘in order to keep themselves from sliding over into the abyss of commitment’. This trait survives into the twenty-first century, but I have a different theory to explain it. I have met very rich people who don’t speak much because it is too much effort. Such emotional and intellectual fulfilment as the hyper-rich male requires often appears to be met by the playing of golf. In fact most of his energy, social and physical, seems absorbed by it. He has grown so rich that he can’t be bothered to finish his sentences. It is as if the very effort of talking at all seems an unwarrantably intrusive demand on his now priceless time and energy. He proceeds on the assumption that those set upon this world to serve him and accommodate his whims (most of the rest of the human population, including his wife) should be obliged to operate with antennae constantly tuned to his own wavelength, so that the barest minimum of words on his part should be enough to head them in the right direction in the meeting of his requirements. Indeed the act of communicating at all is irksome to him, an irksomeness that he expresses by the regular insertion of expletives into his half-formed sentences. ‘Fucking Matisse, fucking outasight,’ is as far as one very, very rich client was prepared to go in his aesthetic assessment of one of the gems of his collection when showing me round his drawing room.

While it was fairly clear that as far as Duveen was concerned money was more important than art, his message to his buying clients was that art was more important than money. By buying great art, they were buying immortality, allying their names with Leonardo, Botticelli and Raphael, etc. Reproached for putting a high polish on his old masters, Duveen said his rich clients wanted to see themselves reflected when they looked at works of art. Such was Duveen’s mastery of the market that he rarely bought without in effect pre-selling. He knew what he could afford to pay for a painting or a collection because he knew how much a specific well-heeled client, already seduced by the fantasy of buying into the dream of immortality through art that Duveen purveyed, could be persuaded to pay for it. This was true of the first of Duveen’s big purchases: the Kann collection, for which Joe and uncle Henry paid $4.2m in 1907. It was a purchase that also marked the beginning of business relations with Nathan Wildenstein, a combination of two big beasts that was frequently acrimonious but nearly always profitable to both parties. Almost simultaneously Duveen bought the great Hainauer collection from Berlin. Buyers were already lined up. Altman, Widener and J.P. Morgan all jumped in, as did Arabella Huntington, widow of Collis P. Huntington, who bought Rembrandt’s Aristotle with a Bust of Homer. Very soon Duveen was in profit, and still had lots of desirable stock left over. Arabella Huntington was the sort of woman dealers dream about, a rich and fanatical collector herself and a practiced loosener of the purse strings of the even richer men that she married. Between 1908 and 1917 she and her new husband, Henry Edwards Huntington (nephew of Collis P.), spent $21m with Duveen. Henry Clay Frick was also won over to the Duveen cause when Joe sold him J.P. Morgan’s Fragonard Room, conveniently on view at the Metropolitan Museum (neither the first nor the last instance of a dealer taking advantage of the exhibition of privately owned art in a major museum to make a sale, bolstered by the authority of the museum exhibition). Over time collectors such as Altman were rewarded on a new variation of the ‘Ars longa, vita brevis’ principle. The department store that bore his name went out of business, but it lives on as a wing in the Metropolitan Museum. No one in Britain wants to see Sainsbury’s go out of business, but should the worst happen the name will live on in the wing at the National Gallery. And Duveen himself, ever keen to emulate his clients, is immortalised in his galleries at the Tate.

Duveen’s strategy of paying – and asking for – very high prices for his stock was an intelligent one. At the stratospheric level of the market you are by and large protected from fakes. Duveen knew enough to be buying the very best, with immaculate provenance and unimpeachable authenticity (often provided in-house by Berenson). Shelling out a lot of money is in itself attractive to a certain sort of buyer, who takes comfort, pleasure and cachet from paying the highest price of the year. And history shows that generally the very best goes up quicker than the merely good (always allowing for shifts in taste, which is the unknown factor in all this).

A further element in the Duveen business model was the ‘grand’ intermediary who was happy to take discreet payment from the dealer for delivering to his premises fellow aristocrats or rich Americans as sellers or buyers, but needed at all costs for the commission he received to be kept secret in order to preserve his unsullied reputation in society. Joe cultivated distinguished British middlemen, peers like Lord Esher and Lord Farquhar, who were responsible for introducing royal patronage to Duveen. Farquhar, for instance, besides conducting a profitable trade in honours, pointed Duveen in the direction of fellow aristocrats in money trouble. In return Duveen furnished Farquhar’s houses and never sent him a bill. The bitter Berenson wrote that Duveen ‘stood at the centre of a vast web of corruption that reached from the lowliest employee of the British Museum to Buckingham Palace itself’. Berenson’s worst fears were confirmed as Duveen himself was created first a knight, in 1919, and then a peer of the realm in 1933.

Duveen was constantly inventive about works of art. He was quite prepared to reshape them in a form that was more pleasing to his clientele. Even in the 1970s, the old master department at Christie’s could be cast into gloom by a Gainsborough portrait in oval format. That was certainly not the Duveen spirit. Under Duveen’s instruction less commercial oval portraits were cut down into more commercial rectangular shapes, and everyone was happy. The client was always right after all. Sometimes even more esoteric requests were made: one client, the American Carl Hamilton, wanted young boys: ‘young fellows – about 12–13 years’, that he’d like to take home to America and adopt. Amazingly, Duveen obliged. A French one and a Spanish one were provided. It was perhaps this that Berenson had in mind when he confided bitterly to René Gimpel:

in Florence the Yankee becomes an art lover between a visit to a little girl and one to a little boy, a flourishing trade here. The middleman who deals in works of art follows close on the heels of the procuress; often they are one and the same. They invariably know how to find somewhere in the same town the twin brother of the picture admired in the museum, and the American flings himself into this new kind of debauchery at fantastic cost. But there at least he isn’t risking the dread disease; only the picture is contaminated!

Berenson, despite his increasingly critical attitude towards Duveen, had to admit that he was an artist as a salesman. ‘He would make you pay outrageously, he would exact the last possible penny in a deal, and then would spend thousands of dollars on you with the most open-handed generosity.’ Duveen’s mantra was a simple but beguiling one to American millionaires: ‘When you pay high for the priceless, you’re getting it cheap.’ Frick found practical ways of reassuring himself that Duveen’s high prices were actually rather reasonable. Frick’s research revealed that Philip IV had paid Velázquez the equivalent of $600 for a work for which Duveen was now asking $400,000. Frick compounded $600 at 6 per cent per annum from 1645 to 1910, and to his joy came up with a sum that made the $400,000 look like a bargain.

Even the greatest art dealers are a bit like plumbers when it comes to discussing their rivals’ wares with clients. The sigh and shake of the head that plumbers are so good at when inspecting another plumber’s handiwork looked amateur by comparison with Duveen’s reaction to a fellow professional’s goods. It was beautifully judged: a sharply raised eyebrow, an exhalation of disbelief and a world-weary shake of his head that spoke not so much of anger but rather of sorrow at the cupidity of humankind; and of relief that, at least in this instance, he was on hand to protect an innocent consumer – who was also a friend, because Duveen’s clients were his friends – from making a costly mistake. ‘On one occasion,’ records Behrman, ‘an extremely respectable high church duke was considering a religious painting by an old master that Agnew’s, the distinguished English art firm had offered him. He asked Duveen to look at it. “Very nice, my dear fellow, very nice,” said Duveen. “But I suppose you are aware that those cherubs are homosexual.”’ On another occasion a prospective buyer of a sixteenth-century Italian painting offered him by another dealer ‘watched Duveen’s face closely and saw his nostrils quiver. “I smell fresh paint,” said Duveen sorrowfully’.

The reassuringly vast sums that Duveen charged his clients only became a problem in the event that the buyer decided to resell the work in question. On the rare occasions when Duveen’s best clients did return pieces to the market, Duveen would move heaven and earth to keep up their prices in a kind of successful Ponzi scheme, by providing other favoured clients to buy them at even higher levels. The so-called Baldovinetti that caught Kenneth Clark’s eye on his visit to Duveen’s premises in 1936 is an instructive case in point. Joe originally bought it on Berenson’s recommendation in Florence in 1910 for $5,000; even then it was acknowledged to be much repainted, quite possibly by the vendor, a notoriously creative restorer. Nonetheless, it was sold by Joe to William Salomon for $62,500. When Salomon wanted to get out of it, Joe sold it to another rich client, Clarence Mackay, for $105,000. When Mackay went bust in the Depression, Joe took it back. Hence its appearance on Duveen’s walls when Kenneth Clark called. But it was only there briefly because the same year Joe sold it on to Samuel Kress, who in turn gave it to the National Gallery in Washington. This last stage in the sequence, the donation to Washington, was an even more effective way of insuring that no one lost out. Persuading his biggest clients to endow museums with their collections was a brilliant scheme on Joe’s part. Besides achieving them immortality, there were tax advantages too, to which his clients responded equally positively. It was genius. In the words of Behrman, at a stroke ‘oblivion and the Collector of Internal Revenue were circumvented’. Huntington, Frick, Mellon, Bache and Kress were all persuaded into this kind of philanthropy by Duveen. In fact in 1936 Joe sold Andrew Mellon $21m-worth of paintings and sculpture from Duveen stock in order to fill in gaps in the embryonic collection of the National Gallery in Washington. Puritan guilt was assuaged, and the agony of wealth was dulled. The art of atonement was atonement through art. Sadly, however, some of the Duveen swans turned back into geese over time in Washington: the so-called Baldovinetti now languishes in storage in the National Gallery, its attribution uncertain.

In preparation for an encounter with a prospective purchaser, Duveen sometimes staged role-playing sessions, with his secretary impersonating the client. He was a master at creating desire through insecurity. A new collector coming to Duveen for the first time always got told he couldn’t buy from him. Whatever caught his eye was invariably reserved for someone else. ‘As a novice in collecting I expected to have to pay the highest prices for masterpieces,’ admitted Albert Lasker. ‘What I did not expect was that I would also have to pay a large premium for the privilege of paying the highest prices.’

That was Duveen as a seller. As a buyer, he had runners all over Europe, ‘franc-tireurs routing out hard-up noblemen with good pictures’. When dealing with British sellers, in the words of Behrman, ‘he didn’t waste breath on art patter. He just talked money.’ ‘I can’t pay you £18,000 for this,’ he announced regretfully to one titled seller. ‘I insist on £25,000.’ He simply didn’t understand small amounts of money. In England he played the role of the generous buffoon, the court jester to the aristocracy. In America he played the aristocratic Englishman (which he managed to do with conviction once he got himself ennobled). Osbert Sitwell wrote of Duveen’s ‘expert amiability, which resembled that of a clownish tumbler on the music-hall stage’. Sitwell went on: ‘Being a remarkably astute man in most directions, I think that… he enjoyed having the stupid side of his character emphasised; it constituted a disguise for his cleverness, a kind of fancy dress.’ And Duveen was a generous benefactor of the nation, but even this was an act of brilliant prestidigitation, a sort of cultural three-card trick: the public galleries that he paid for in Britain were actually funded, in Sitwell’s words, ‘by the sale to the United States of the flower of the English eighteenth and early nineteenth-century paintings. We have the galleries now, but no pictures to hang in them.’

He lived better than his millionaire clients. I used to wonder if this made clients suspicious when negotiating with an art dealer. But on balance I think the extraordinarily rich are reassured by extraordinary wealth. They prefer to pay 25 per cent more to be dealing with one of their own. Because clients such as J. Pierpont Morgan dealt in large sums and made large profits, ‘he conceded to his dealer the same privilege,’ in the elegant words of Germain Seligman. Indeed he expected it. Like most of his clients, Duveen was not an intellectual and seldom read anything. Again, not much has changed. I once sent a book I had written to a leading New York gallerist, who shares some of the characteristics of Lord Duveen. ‘Did you enjoy it?’ I asked him – in a shameless attempt to elicit praise – some months later. ‘Yeah, it was good,’ he told me. ‘I had it read.’

Lawsuits gave Duveen’s life savour. In 1897 a tiresome new US Revenue act had imposed a 20 per cent tariff on imported works of art. In 1909 this was repealed to allow duty-free exemption on works of art more than 100 years old, a cause of unconfined joy in the American art trade. In the ‘difficult years’ leading up to 1909, Duveen kept two account books – one real and another a work of fiction, for the eyes of US Customs. Unfortunately a whistle-blower within the Duveen organisation revealed the deception to US Customs, and Duveen was prosecuted for the evasion that had taken place up till 1909. A great art dealer needs a great lawyer and Duveen found one in Louis Levy, who represented Duveen in this and all his future American litigations. It was sorted out in the end, and a penalty fine of $10m was whittled down to $1.2m, still a substantial sum. Joe, typically, was rather proud of the magnitude of the settlement. And of course the removal of the tariff now opened up the US market still further. But you had to think on your feet as an international art dealer even in 1909. That year a law came into force in London imposing UK tax on overseas branches of UK companies. Deftly Duveen shifted his business to New York and Paris. This was the reason why sales at Duveen in Paris in 1913 amounted to more than $13m. They included Raphael’s Cowper Madonna, for which Duveen apparently paid $500,000 that year and sold to P.A.B. Widener almost immediately for $700,000.

In 1920, the year after Duveen’s knighthood, his firm’s net profits were $710,032. The stage was set for a booming decade, during which he added to his already glittering client list Andrew Mellon, Randolph Hearst, Julius Bache (codename Julie) and Clarence Mackay, a new generation of huge American wealth who all began buying. It was to H.E. Huntington that he sold Gainsborough’s Blue Boy in 1922 for the staggering sum of $728,800, having somehow persuaded the Duke of Westminster to part with it. On top of that Duveen also contrived a three-week farewell exhibition in the National Gallery, London when it was announced that the painting was leaving British shores. Cole Porter even wrote a song about it – ‘The Blue Boy Blues’ – which celebrated the portrait’s journey from ‘the gilded galleries of Park Lane’ to the primitive western frontiers of America.

Yet one more major lawsuit, which lasted off and on through most of the 1920s, was the affair of La belle ferronnière. (It was almost as if Duveen orchestrated it as an entertainment to brighten his otherwise monotonously successful progress through the decade.) The fact that Duveen was not a connoisseur of Italian pictures did not deter him from pontificating loudly on them. René Gimpel recorded: ‘He has no knowledge of painting and sells with the support of experts’ certificates, but his intelligence has enabled him to keep up a cracked facade in this country, which is still so little knowledgeable.’ Andrée Hahn, a lady in Kansas, claimed to own a Leonardo, a version of La belle ferronnière in the Louvre. Duveen was asked his opinion of it, and roundly condemned it as not authentic. The Hahn family then sued him for fouling up a sale they were negotiating. They proved remarkably tenacious litigants. Though they had very little right on their side, they eventually accepted an out-of-court settlement of $60,000 in 1930, but not before Duveen himself had made court appearances in the course of which he claimed infallibility as to authenticity (although he admitted he didn’t always know attribution). A less willing expert witness was Bernard Berenson, although he too had his moment of majesty in one hearing, as recounted by René Gimpel:

The lawyer asked him [BB]: ‘You’ve given a good deal of study to the picture in the Louvre?’

‘All my life; I’ve seen it a thousand times.’

‘And is it on wood or canvas?’

Berenson reflected a moment and answered: ‘I don’t know.’

‘What, you claim to have studied it so much, and you can’t answer a simple question?’

Berenson retorted: ‘It’s as if you asked me on what kind of paper Shakespeare wrote his immortal sonnets.’

It is a masterful reassertion of eighteenth-century connoisseurial values on Berenson’s part, an underlining of his superiority to the mere technician. Berenson’s position is ‘I don’t know what it’s painted on but I know it’s beautiful’, as against the technician’s ‘I know what it’s painted on but I don’t know whether it’s beautiful.’

At the end of the 1920s came the slump. ‘Julie’ Bache had $4m of Duveen pictures in his possession that he hadn’t paid for, but he didn’t dare return them for fear of word spreading that he was broke. Duveen suffered too: in 1929 the firm recorded a loss of $900,000 and this rose in 1930 to $2.9m, but he still carried on with style, and it seems likely that he was given advance warning of the stock market crash by his friend Calouste Gulbenkian and pulled out his money in time. One Saturday morning soon after the Wall Street disaster Alfred Erickson of McCann Erickson, who had bought Rembrandt’s magnificent Aristotle with a Bust of Homer from Duveen for $750,000, called on him. Duveen immediately made out a cheque for $500,000; generous, but not of course a refund of the full purchase price. Still, Duveen allowed Erickson to buy it back for $590,000 when times were better.

There are different kinds of dishonesty. Collis Huntington, one of the grosser examples of the first generation of American mogulhood, was once described as ‘scrupulously dishonest’; he was the sort of operator who in the twenty-first century would do dubious deals behind the cover of a high-profile legal compliance department. But Duveen was thrillingly dishonest, intoxicating in his bravado. He might take your money off you but he made you feel good in the process, and you sometimes ended up with quite a decent picture from him, even if you’d overpaid for it. ‘He was irresistible,’ wrote Kenneth Clark. ‘His bravura and impudence were infectious, and when he was present everyone behaved as if they had had a couple of drinks.’ Duveen thrived on risk, on surmounting obstacles he had strewn in his own way by an injudicious criticism or praise of a work of art. He couldn’t help going over the top. Berenson’s dishonesty, on the other hand, crept up on him: ‘You know the beginnings of evil are apt to be very good,’ he confided to Kenneth Clark in 1934.

A generation of early-twentieth-century moguls in America were taught by dealers such as Duveen, Seligman, Knoedler, Agnew, Colnaghi and Wildenstein to revere the Italian Renaissance beyond anything, and to express that reverence by spending large amounts of money on its works. This involved new levels of education and expertise to back up the high prices, provided by Duveen through the crucial medium of Berenson. How far was the cult of Giorgione, for instance, stimulated by the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century art trade? Titian, as the leading artist of the Venetian school, was a known and highly desirable quantity. Kings, emperors and the upper echelons of the aristocracy had vied for his works for centuries. But dealers now found that Giorgione offered an extra piquancy. Besides genius, Giorgione had romance. He was responsible for the injection into early-sixteenth-century Venetian painting of an irresistible element of mysterious longing, seized upon by Walter Pater in an essay entitled ‘The School of Giorgione’ (1877) to conjure very nineteenth-century dreams of yearning shepherds in an idyllic Arcadia playing pipes to the sound of plashing water.

And Giorgione had something even more desirable to offer than genius and romance: he died young. ‘To live for only 33 years,’ wrote Reitlinger of Giorgione, ‘is to give a lot of trouble to art experts’ – but a lot of opportunity to clever art dealers. The fact that there was a certain flexibility to his oeuvre, that he was rarer than Titian, that no one quite knew where Giorgione ended and early Titian began, but that he was widely regarded as having had more influence over Titian at this early stage than vice versa, all were played upon by the trade to make Giorgione a more desirable commercial proposition even than Titian.

The dispute over the beautiful Nativity that Duveen managed to buy from Lord Allendale in 1937 was the final point of conflict between Duveen and Berenson, and precipitated the end of their business relationship. It all hinged on whether Berenson was prepared to attribute the work to Giorgione rather than Titian. As a Giorgione it was definitely worth more. Berenson had been prepared to do it in 1913 with the portrait of Ariosto, which had been transmuted from a Titian to a Giorgione in order to make a sale to Altman. But in a gesture born of bad conscience or bad temper he now refused to give Duveen the confirmation he wanted. Indeed it is possible to argue that the shrinkage of Giorgione’s accepted oeuvre in the mid-twentieth century is a direct reflection of Berenson’s remorse at his embroilment in the art trade, a retrospective reassertion of over-rigorous scholarly standards. Only three or four works were definitely accepted as by his hand. While Berenson still lived, Giorgione became forbidden and much-reduced territory. Only after Berenson’s death did it become possible, in Reitlinger’s words, ‘to repeat Giorgione’s name in something above a hoarse whisper’. Nonetheless Duveen still managed to sell the Allendale Nativity to Samuel Kress at a considerable profit, even though its attribution was marooned somewhere between Titian and Giorgione. It was one of his final deals.

Joe was good company and had an impish sense of humour: Dick Kingzett of Agnew’s recounted how in his youth he was at a dinner in the summer of 1938 with Duveen, who spoke to him exclusively about cricket. Did Kingzett not agree that Jack Hobbs was the finest batsman who ever lived? A fellow guest, the rather more aesthetic Eddy Sackville-West, tried to turn the conversation to opera, and mentioned Don Giovanni. ‘Ah,’ said Duveen, ‘the Don. Now in my view Don Bradman is the greatest batsman playing today…’ The grandeur of the circles in which Duveen moved is constantly amazing. He was popular with courtiers, peers and even prime ministers. Ramsay MacDonald was comprehensively seduced by the Duveen charm, which was indeed enough to turn a socialist into a socialite. Joe’s entertaining was constant and sumptuous. Jean Fowles, wife of Edward, describes the effect of his eyes, which were ‘a brilliant, hypnotic blue’. Apparently Duveen had a vast aquarium in his entrance hall, but he confessed to Jean Fowles that he was disturbed by the inactivity of the fish – they never did anything – so he was thinking of replacing them with a huge cage of monkeys. Lady Duveen objected to the idea because of the smell. That wouldn’t be a problem, said Duveen. He would have them constantly sprayed with Guerlain perfume. It was a metaphor for his art dealing.