THE ENRICHMENT OF AMBROISE VOLLARD

It took a certain sort of character to become a dealer in difficult modern art in late-nineteenth-century France; a cussedness, a thick skin and a pleasure in the unusual. The Ambroise Vollard who arrived in Paris in 1887 aged twenty-one was a colonial and an outsider. He had been brought up on the island of Réunion, a remote outpost of the French Empire in the Indian Ocean. Is this outsiderhood also one of the reasons why he responded almost immediately to the new art? He was tall and maladroit, and determined to the point of obstructiveness; on top of that he had a keen sense of the ridiculous, and a strong subversive streak. Probably all of those characteristics helped in the formation of an art dealer prepared to do battle on behalf of artists most of the public thought of as madmen.

Not that Vollard arrived in Paris determined to be an art dealer. He had been sent to study law, but soon found he was happiest rummaging second-hand stalls on the quays of the Seine for engravings and drawings. He gave up his law studies to work full-time at a dealership called Union Artistique, which specialised in selling the work of Salon artists such as Édouard Debat-Ponsan, a purveyor of images of picturesque countryfolk treated in a mildly plein-airist style. Vollard first saw the work of Cézanne at the shop of Père Tanguy, an elderly ragamuffin with faintly communard sympathies who patronised new painters ‘in whom it pleased him to see rebels like himself,’ as Vollard later put it. Vollard knew that Cézanne spoke to him in a way that Debat-Ponsan never could, and in 1893 he went solo, breaking away to set up his own somewhat ramshackle gallery in rue Laffitte specialising in advanced contemporary art. His gallery became, in his own words, ‘a sort of pilgrims’ resort for all the young painters – Derain, Matisse, Picasso, Rouault, Vlaminck and the rest’. But the first important show he put on was of Édouard Manet, after he had got hold of a cache of sketches from the artist’s widow. It is interesting that Vollard, as with Durand-Ruel, found his engagement with modern art fired by an early enthusiasm for Manet. But for Vollard the transforming experience was his discovery of Cézanne, to whose work he gave a famous solo exhibition in November 1895.

We do not know exactly what went through Vollard’s mind when he first saw a painting by Cézanne, but he called it a ‘coup à l’estomac’. It was one of those revelatory moments people occasionally experience in front of art that strikes them as totally new and marvellous. If they are art dealers, the way forward is clear to them. Here is the artist they will promote, establish and make money out of. The Cézanne show that Vollard mounted in his gallery was composed of works he had managed to buy either from the sale of the estate of Père Tanguy (who died in 1894) or from the artist himself, with whom he had made contact in Provence. He was single-minded in his conviction of Cézanne’s importance, and in his acquisition of his work. For the next ten years, until the artist’s death in 1906, Vollard held a virtual monopoly in his drawings and paintings. The enthusiasm between artist and dealer was mutual. ‘I am glad to hear that you like Vollard, who is at once sincere and serious,’ wrote Cézanne to the artist Charles Camoin in February 1902. As for Vollard, ‘Cézanne was the great romance of Vollard’s life,’ says Gertrude Stein. Overall, more than a third of Cézanne’s output passed through Vollard’s hands at some point.

He bought and exhibited works by van Gogh, too. And with Gauguin, now domiciled and commercially impotent in the South Seas, he entered – exceptionally – into an exclusive, albeit miserly, contract. ‘He shows nothing but pictures of the young,’ said Pissarro approvingly. ‘I believe this little dealer is the one we have been seeking, he likes only our school of painting…’

Vollard was a bachelor, and as mentioned previously, the fact that he never married and did not have the financial responsibility of a family played in his favour as a dealer. Durand-Ruel, by contrast, in the difficult early days found himself a widower with six young children to support and, unable to hang on to his stock, had to sell much of it cheap. Vollard’s domestic style was different as well. He gave famous dinners in his cellar at rue Laffitte, where he served chicken curry (a recipe brought with him from Réunion). His guests were generally artists, most often Cézanne, Renoir, Degas, Forain and Redon.

Vollard recounts in his Recollections the following dialogue between himself and a prospective buyer at his gallery:

‘How much are those three sketches by Cézanne?’

‘Do you want one, two, or three of them?’

‘Only one.’

‘Thirty thousand francs, at your choice.’

‘And if I take two?’

‘That will be eighty thousand francs.’

‘I don’t understand. So then all three would be…?’

‘All three, a hundred and fifty thousand francs.’

My customer was flabbergasted.

‘It’s perfectly simple,’ I said. ‘If I sell you only one of my Cézannes, I have two left. If I sell you two, I have only one left. If I sell you all three, I have none left. Do you see?’

I reproduce this exchange with some shame and trepidation. It goes against all the precepts of salesmanship now taught so religiously to operatives in the great auction houses. Week-long seminars and training courses are conducted by fresh-faced Americans with degrees in business studies and behavioural science that emphasise the simple central lesson that the client comes first. Don’t tell him why it’s a good deal for you, tell him why it’s a good deal for him. Dwell on the joy of his owning not one but three works by the master. It seems tragic that Vollard should have been denied such wisdom, and perplexing (to the fresh-faced Americans, at least) that he was nonetheless so successful at selling paintings.

Early on in his career Vollard established a reputation for unconventional dealing strategies. Once, when selling a drawing by Forain he quoted a price of 120 francs. The buyer offered 100 francs. Vollard retaliated by raising the price to 150. As Walter Feilchenfeldt suggests, whereas Vollard was close to his artists and appreciated by them, he had a certain contempt for his clients. ‘In picture dealing,’ Vollard wrote, ‘one must go warily with one’s customers. It does not do, for instance, to explain the subject, or show which way up a picture is meant to be looked at.’ He takes a wry pleasure in the absurdities of art buyers. He was particularly amused by a group of connoisseurs who, having seen the works of three ‘madmen’ – Cézanne, Gauguin and van Gogh – rise dramatically in price, convinced themselves that the next sort of painting that would miraculously go up in price could best be identified by other madmen. They hatched a plan to create an investment fund, ‘which they put at the disposal of some half-witted creature, and despatched him to Paris accompanied by a delegate of the group, whose function it was to send home the pictures selected by the lunatic’. For Vollard life is best understood – and relished – as a play staged in the Theatre of the Absurd. He recounts with pleasure the response of the critic Albert Wolff to an author who had begged him to write an article on his work: ‘A eulogistic piece will be 25 louis. A thrashing, 50 louis.’

Vollard knew himself, and his own shortcomings: ‘How many times have I not regretted that nature has not endowed me with an easy-going, jovial manner,’ he reflected in his Recollections. His ideal client was the American collector Dr Albert Barnes, whose merits as a buyer of paintings Vollard describes succinctly: ‘Unhesitatingly he picks out this or that one. Then he goes away.’ But I suspect that Vollard quite enjoyed (and exploited) his own reputation as a curmudgeon. Certainly he enjoyed the little tricks of the art trade, the feints and deceptions, the detective work, and the thrill of the chase. In Recollections he tells with admiration of a fellow dealer who dresses up his clerk as an American private collector in order to visit the house of and do business with an owner who refuses to have any commerce with dealers. He was capable of ruthlessness in dealing with rivals. After he beat down the unfortunate Berthe Weill (a fellow dealer in avant-garde art, a lady who one can’t help feeling deserved more gallant treatment) on a Redon to a shamefully low price, he had no compunction in then telling the artist that he shouldn’t sell her any more work because she was ruining his prices.

In 1901 Vollard showed that he was tapped into the most forward section of the avant-garde by giving the young Picasso his first exhibition in Paris. Opening on 24 June, it comprised sixty-five hastily assembled pictures and an unknown number of drawings. The event was neither grand nor well publicised. Vollard’s presentational skills were never his strength, and Picasso was barely twenty, an unknown Spaniard newly arrived in France. What did he see in Picasso at that point? An energy, an exuberant relish of colour that prefigured the Fauves, a distinctively Spanish gusto. It seems that about half the exhibits sold, which was a pretty successful outcome. But Vollard didn’t stay with Picasso after that: he didn’t like the Blue Period works that followed. Vollard’s interest in Picasso was renewed with some Rose Period works that he handled in 1906. But Cubism, in the words of John Richardson, ‘utterly defeated’ Vollard. As a Cubist painter Picasso was much better suited to the dealing attentions of the school-masterly Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. It is ironic that Picasso’s portrait of Vollard, painted in 1910, is an exercise in the language of Cubism. Dealers are not sentimentalists: Vollard was perfectly happy to sell it on to the Russian collector Ivan Morozov for 3,000 francs two years later.

Picasso’s Cubist portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1910), incomprehensible to the sitter.

Vollard also gave Matisse his first solo exhibition, in 1904, but missed out on him. When Matisse finally contracted himself to a dealer, it was to Bernheim-Jeune in 1909. Still, one of the Fauves Vollard did get was Derain, to whom he was introduced by Matisse in November 1905. He had the resource to gamble on unknowns, and to do so in large numbers. He spent a modest 3,300 francs on eighty-nine paintings by Derain. Apparently he barely looked at them as they were loaded into his car, but he already had a plan for Derain. Part of that plan was to send him to London. The recent successful exhibition at Durand-Ruel’s gallery of the works Monet painted there made a deep impression on both Vollard and Kahnweiler. Vollard despatched Derain to produce a series of London paintings in 1906; Kahnweiler tried, but could not persuade Picasso to do the same. On the face of it, grey, fog-bound London was a surprising location for a Fauve to paint in. But here is an instance of a dealer having an impact on the history of art. The series of London views that Derain produced were striking and important landmarks in the development of Fauvism, and wouldn’t have been painted without Vollard. Together with Monet’s 1901 series, they also stood in good stead later generations of art dealers, on the basis that many rich collectors live in London and are delighted to put their money into works by great Modernist masters that depict familiar surroundings (see plate 10).

Ambroise Vollard: a lithograph by Renoir.

The Vollard stock books tell a happy story of ever-increasing distance between the price of the thing sourced and that of the thing placed. In spring 1906, for instance, he buys a Gauguin self-portrait from Victor Segalen for 600 francs; he sells it to Prince de Wagram less than two months later for 3,500. In December 1899 he buys from Cézanne’s brother-in-law two landscapes for a total of 600 francs. A letter survives from Vollard in which he regrets being unable to pay more, because ‘still lifes and flowerpieces are preferable to these unpolished landscapes’. But you can be sure that the lack of polish and the greater desirability of still lifes were not mentioned when he sold one of the landscapes to the German collector Karl Osthaus in April 1906 at a considerable mark-up, and certainly not when he sold the other in March 1922 to Coe of Cleveland for more than 100,000 francs. His virtual monopoly of Cézanne in what was by the first decade of the twentieth century a rapidly rising market for the artist meant that he could pick and choose when and what he sold of his large holding of the artist’s work. To all intents and purposes Vollard’s financial future was now not just secure, but looking very rosy indeed. It gave him the freedom to experiment in other areas, notably publishing.

Vollard’s closeness to his artists is reflected in the extraordinary number of portraits they painted of him: there are memorable and multiple images by, for instance, Renoir, Cézanne, Bonnard and of course Picasso. As Picasso remarked, ‘the most beautiful woman in the world never had herself painted as often as Vollard’. Such was the lasting visual impression that Vollard made on Picasso that much later in life, when carving a slice of tongue, Picasso held it up to remark upon its chance resemblance to the features of the dealer. Vollard’s impact was considerable, both physically and intellectually, which was perhaps what fascinated painters: Vuillard describes him as ‘serious, ironic, enormous and spirited’.

That sense of irony is an important thread in Vollard’s make-up. René Gimpel records how, after some perfidy of Degas over prices, Vollard observed wryly: ‘You can only trust the talentless artists to keep their word.’ During the First World War Vollard’s irony emerges more forcefully, as a cynical relish of the absurd, a commodity never in short supply during the conflict. Père Ubu, the alter ego in whose voice Vollard wrote a number of laconic short stories, recounts in ‘Le Père Ubu a l’Hopital’ how a senior medical officer (a ‘Five Stripes’) amputates the leg of a wounded soldier, reprimanding a junior military surgeon (a ‘two-stripes’) who has had the effrontery to cure a similar case without operating. ‘The Censorship opposed publication of my story for cogent reasons,’ reported Vollard later, continuing,

and I came round, of my own accord, to a saner appreciation of the military method. For it is easy to see how contrary to all hierarchy, and even to common sense, it would be if a ‘Four Stripes’ were not twice as clever as a ‘two-stripes’. Obviously any cure obtained by an inferior, after a man of superior rank has failed, can only be considered null and void. I wrote my Ubu à la Guerre to this effect, and this time the Censorship bestowed its full approval.

His preference for artists over collectors is a feature of Vollard’s dealing life. But he makes an interesting observation about collectors of the new art: he prefers Germans to the French. He describes it as ‘a singularly paradoxical situation’ that ‘the Frenchman, who is argumentative by temperament, becomes a conservative when confronted by any new trend in art, so great is his need of certainty, and so afraid is he of being taken in. The German, on the contrary, while bowing instinctively to anything in the way of collective discipline, yet gives enthusiastic support to every anticipation of the future.’

Presentation of works of art in Vollard’s ‘gallery space’ was not one of his strengths. Contemporary accounts of the chaos that prevailed indicate that Vollard, had he lived a hundred years later, would have benefited from the courses that international auction houses now offer their staff, aimed at ‘improving the client experience’. Certainly Gertrude and Leo Stein, when they first went there, had difficulty in making their requirements understood. ‘It was an incredible place,’ said Gertrude Stein. ‘It didn’t look like a picture gallery. Inside there were a couple of canvases turned to the wall, in one corner was a small pile of big and little canvases thrown pell mell on top of one another.’ By contrast with the grand premises and persuasive selling technique of a dealer like Georges Petit, Vollard was a secretive hoarder. There was no hard sell: Gertrude Stein goes on to describe him as ‘a huge dark man glooming. This was Vollard cheerful. When he was really cheerless he put his huge frame against the glass door that led to the street, his arms above his head, his hands on each upper corner of the portal and gloomed darkly into the street. Nobody thought then of trying to come in.’

The Steins’ first attempt to buy a Cézanne landscape from Vollard was not untypical. He brought them everything but the subject matter they wanted, disappearing upstairs and returning with first an apple, then a painting of a human back, then ‘a very large canvas and a very small fragment of landscape painted on it’. Would it be possible to have ‘a smaller canvas, but one all covered,’ they ask? At this point a couple of elderly charwomen follow each other downstairs and exit the premises. Gertrude Stein wonders if the artist called Paul Cézanne doesn’t actually exist, but it’s these two women who knock up the ‘Cézannes’ in a back room on orders communicated a trifle inaccurately by the proprietor.

But Mary Cassatt admired Vollard as a seller: in December 1913 she wrote to her friend and client the great collector Mrs Havemeyer: ‘Durand-Ruel would not buy the things from Degas that Vollard gladly took and sold again at large profits. Vollard is a genius in his line, he seems to be able to sell anything.’ But how? ‘Doing business with Vollard was always something of a feat,’ remembered Ruth Bakwin, ‘because most of the time he discouraged buyers from purchasing his paintings.’ When Mrs Havemeyer actually went herself to buy Cézannes from Vollard, he kept her waiting while he continued the conversation he was having with an artist. Mrs Havemeyer indicated she would miss her boat. Vollard politely answered, ‘Madame, I am certain you could take another boat.’ She did. The key of course is that the only way to buy Cézanne at that time was to go to Vollard. Vollard was operating from a position of strength. His monopoly gave him powerful muscles, which he rather enjoyed flexing. He had great international contacts and understood the benefits of lending his stock extensively, for instance to Cassirer in Berlin for a succession of exhibitions, to Roger Fry in London for the Post-Impressionist show in 1910, and to the Armory Show in New York in 1913, where he sold conspicuously more than any other European dealer.

In his later life Vollard formed a close attachment to the wife of an old friend, Madame de Galea, but he would have been a difficult man to live with. His bachelor habits grew more marked as time went by: Daniel Wildenstein remembers the elderly Vollard as living in fear of catching a cold and being pathologically stingy. ‘Vollard give something away? Don’t make me laugh,’ exclaimed Wildenstein. But you can detect a grudging admiration in his tone. The big beasts locked horns when the Wildensteins attempted to do business with Vollard in the 1920s and 1930s. ‘We would go to his place one or two times a week to try to buy a painting from him,’ remembered Daniel. ‘Everything was always on the ground, in piles… If you wanted to buy a Cézanne from him, you needed to ask for a Renoir. Not a Cézanne, certainly not that. A Renoir… And then with a little luck he would take out a Cézanne.’ Was this his sense of the absurd, his consciousness of his own strength, or very subtle salesmanship? Perhaps a bit of all three.

So identified with successful moneymaking had he become in the mind of the young Jean Renoir, the artist’s son, that initially he was convinced that the unit of currency in the USA was a Vollard, not a dollar. ‘Vollard is a tall awkward person, earnest, simple and engrossed in linking his name with modern art history,’ noted the New York art critic Henry McBride in 1915 when introduced by Gertrude Stein. ‘He has a trick of shutting one eye tighter than the other which gives an oblique line across the face.’ Daniel Wildenstein described him in later years as ‘massive, with a baritone voice, small beard, and a beret that covered his bald spot’. ‘He was a sort of alert old bear,’ said René Gimpel.

In March 1920 Vollard told Leo Stein that he now preferred writing books to selling paintings, especially since people were buying art as an investment. His objection to art as investment was not the high-principled one articulated by others, of art mattering more than money. It was the galling thought that the new owners would make profits from the paintings he sold them – profits he could make himself if he hung on to the wretched things – as the market continued on its apparently inexorable path upwards. It was intolerable. ‘What’s the use of letting the other fellow profit by it?’ he moaned to Stein. It was better not to sell at all.

Of course the lesson of the half century from 1875 to 1925 was that any dealer who ‘defends’ and promotes new art does so partly on the grounds that the new artists they are introducing to the public are going to increase in value. It is an underlying premise that is essential to their financial functioning. And it is a compelling argument, too, for the prospective purchaser. The work might look a bit strange now, but in ten or twenty years’ time maybe that strangeness will have been transformed into its most desirable feature, and maybe it will be worth a lot more. If an investor in the stock market picks a share that goes up dramatically thereafter, he is lauded for his commercial acumen. If an investor picks a young artist whose work goes up dramatically in the ensuing years, he is lauded both for his commercial acumen and for something even more desirable: his aesthetic discrimination. The wise art dealer doesn’t lose sight of that distinction.

But Vollard had done well enough to turn away from the routine buying and selling of paintings in the years after the First World War. He was certainly prepared now and then to undertake an exceptionally remunerative deal – for instance in November 1923 he sold two Blue Period Picassos to the American collector John Quinn for the impressive total of 100,000 francs – but he gave his attention increasingly to his projects as a publisher. Roger Fry paid a visit to Vollard in 1925 and found that all Vollard wanted to talk about was literature rather than art, and particularly his ‘Ubu’ stories, which Fry thought ‘rather silly’. However, ‘the easiest way… to win Vollard’s confidence was to show a keen interest and appreciation of his publications. Indeed many found this the only key that would unlock those secret rooms where the countless masterpieces were stored.’

There is no doubt that Vollard took genuine pleasure in the marriage of art and literature that his publishing ventures blessed; printmaking tied to book publishing offered him a close and satisfying involvement in the product, denied him in the producing of paintings by his artists. And he was very good at it: very good at having the ideas that married artists to texts, and very good at the production of the plates. His printmaking immortalisation was achieved in Picasso’s Vollard Suite, the most celebrated set of etchings that Picasso made, consisting of 100 prints finally published in 1937. Most of them were done in the years 1930–34, arguably Picasso’s most creatively fertile period. Vollard wisely allowed Picasso free rein, and the subjects poured out in wildly experimental print effects: minotaurs, bullfights, lovers, finishing as ever with three etched portraits of Vollard himself, done in 1937.

Vollard is a good example of the lesson that, in order to succeed as an art dealer, one has to cast one’s bread widely upon the waters, and accept that – to change metaphors – not all the frogs one kisses will turn into princes. In the same way that a publisher who manages to attract a range of great writers to his imprint also produces books by authors who don’t make it, so Vollard’s overcrowded gallery was also populated by the works of many painters now consigned to oblivion. A trawl through the gallery records of 1894–1911 shows that Vollard gave shows to a number of largely forgotten names. Today who has heard of Paul Vogler, André Sinet, René Seyssaud or Pierre Laprade? He must have seen something in them. But if you turn to the names of those he handled who did make it – Cézanne, van Gogh, Gauguin, Bonnard, Vuillard, Picasso, Matisse, Derain, Rouault, van Dongen – you realise his strike rate was pretty impressive. He may have wielded a scatter gun, but he knew pretty accurately the direction in which to point it. Renoir, for one, was impressed by Vollard’s judgement of painting. His manner was deceptive: there was a certain indolence to it. ‘He had the weary look of a Carthaginian general,’ said Renoir. But in front of a new canvas he was at his best. ‘Other people argue, make comparisons, trot out the whole history of art, before uttering an opinion.’ But Vollard was different. ‘With paintings this young man was as stealthy as a hunting dog on the scent for game,’ was Renoir’s verdict.

All dealers do regrettable things now and then, and Vollard has been criticised on a number of counts. He was close to Renoir in his old age and admired him as an artist. But later historians have been critical of Vollard’s treatment of Renoir’s studio debris, of his willingness to cut up the larger canvases on which Renoir painted studies into more saleable individual pieces. At least it kept the Japanese happy in the late 1980s with a constant supply of works whose authenticity was more important than their quality. Close study of the Vollard stockbooks also reveals evidence that Vollard was occasionally remiss over sales of works by Cézanne. The records suggest a certain amount of accounting subterfuge was deployed to hide the fact that he paid the Cézanne family a lot less than he made on the paintings and drawings they consigned to him. Then there is Gauguin, whom ‘Vollard acted shamefully towards’, as Matisse put it, in 1952. Vollard is reproached for having been miserly in the prices at which he bought Gauguin’s Tahitian works in the last years of the artist’s life. But it should be said in mitigation that no one else was prepared to offer more. They were difficult to sell. Even Leo and Gertrude Stein ‘thought they were rather awful’ when they first saw Gauguins at Vollard’s gallery. Bonnard was also the victim of unscrupulous behaviour, according to Daniel Wildenstein. He describes how Vollard got hold of a bunch of good Bonnards by taking them from the artist’s studio ‘for consideration’; then Bonnard forgot what he’d handed over and charged Vollard significantly below market value. But the problem was they were unsigned. Vollard did not dare go back for signatures. Daniel Wildenstein comments censoriously, ‘perhaps in Réunion one buys and sells bananas like that, but this was Bonnard!’

In the partially explored territory of the history of art dealing, one area remains especially virgin: the role that restorers play in the success of dealers. The relationship is conducted in a fraught and secret place, but one that might reward the intrepid researcher. Certainly dealers such as Duveen cannot be fully understood without reference to that area of activity. And similarly with Vollard: accusations are sometimes levelled against him in relation to a small number of the many works by Degas that passed through his hands. He bought a large quantity in the Degas estate sale in 1917, and it seems he had very few of them improved by his restorer. Close comparison of these works with what they looked like when they first emerged from Degas’s studio and were photographed as a record for the estate sale in one or two cases show alterations: a face is filled in, or a limb straightened. The problem is that, because it may have happened once or twice, unjustified suspicion is cast on all works by Degas with a Vollard provenance. This is manifestly not fair. Degas was one of the artists for whom Vollard had enormous respect. He even wrote a fond if ultimately unrevealing memoir of him. The vast majority of works by Degas that he handled are excellent examples, and untouched. It was just that when you buy in bulk, which Vollard always liked doing, you will inevitably get one or two duds in the consignment, duds that he very occasionally gave in to the temptation to hand over to the restorer for imaginative reconstruction. Perhaps it was out of loyalty to the artist’s memory. What was it that Max Liebermann once said? ‘It is the duty of art historians to call the artist’s bad pictures forgeries.’ Vollard might have added: ‘And it is the duty of art dealers to present them in their best light.’ Vollard could have adduced in his defence the eighteenth-century theory of Pierre-Jean Mariette, that ‘an experienced connoisseur was authorised to improve a drawing in order to make visible the truth that only a specialist could see’.

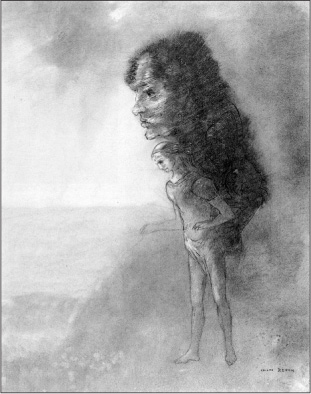

Odilon Redon, La Conscience: a difficult subject for a dealer.

Was Vollard possessed of a moral sense? One can almost hear Daniel Wildenstein exclaiming: ‘Don’t make me laugh.’ But one drawing by Odilon Redon that Vollard owned – and never parted from – suggests that the question of right and wrong occasionally occupied him. The title of the work is La Conscience. Here is Alec Wildenstein, author of the Redon catalogue raisonné, assessing this particular drawing:

Man has become the baggage-carrier of his conscience, which has taken the form of a giant bacteria with a human face. The man, fragile under the burden which is bigger and heavier than he is, advances to the edge of a nothingness which he contemplates, his arms outstretched but hesitant to throw himself into an abyss as unfathomable as the human mystery. Will the man really jump, taking the easy way out? Or will the conscience that weighs him down keep him on the heights so laborious to attain and so arduous to inhabit?

Of course there is another explanation for the fact that Vollard never sold this drawing. He simply couldn’t find a buyer for it. Perhaps none of his clientele – the picture-buying public of the world – wished to grapple with the challenge of its subject any more than he did.

The Vollard estate, in which this work by Redon was included, remained disputed for many years. The dealer who is so successful that he can afford to set aside for himself and his descendants secret stores of masterpieces is an exciting idea. The private storerooms of the Wildensteins have for some time been part of art-world folklore. The same was true of Vollard. No one quite knew what would be revealed after his death, and when it came, in 1939, even that was shrouded in an element of mystery. What is certain is that it was in a motor accident. What is less certain is whether his head was struck by a stray Maillol sculpture also travelling in the car with him. If true, this version would have a symbolic resonance. But John Richardson has a theory that Vollard was actually murdered in an elaborate plot orchestrated by the shady Parisian dealer Martin Fabiani, who had positioned himself to benefit from Vollard’s vast estate. Tracking the disposition of the estate is anyway complicated by the outbreak of the Second World War, but part of it seems to have been stolen by an ex-employee and spirited away to the Balkans. Another part was shipped out of France to America in 1940 by Fabiani, who had apparently bought it from Vollard’s brother Lucien. If this was indeed the final act in a murderous conspiracy, it was itself thwarted by unforeseen events. The boat carrying the shipment was stopped by the British authorities in Bermuda, and the contents confiscated for the remainder of the war on the suspicion that the paintings were going to be sold to raise foreign exchange for Germany. By a historical irony, the man responsible for the confiscation was a young intelligence officer called Peter Wilson, later chairman of Sotheby’s. It is one of the very few instances of a collection of such quality being in his hands without his immediately inveigling it under the hammer. Regretfully he had to pack it off for detention in Canada for the next five years. The remaining part of the Vollard estate was sealed up in a Parisian bank for many decades. After lengthy legal negotiations there was a sense of Peter Wilson’s shade finally being placated when Sotheby’s were entrusted with its sale in 2010. Sotheby’s marketed this final manifestation of the Vollard legend as ‘Trésors du Coffre Vollard’.

What would have happened to the development of modern art if Durand-Ruel had not adopted the Impressionists as his cause? And how would it have progressed if, two decades later, Ambroise Vollard had not discovered and promoted Cézanne? Vollard’s championing of him (and to a lesser extent of Gauguin and van Gogh) opened up recognition for the artists in the early years of the twentieth century. Would their influence – so crucial to the evolution of Cubism and abstract art – have been felt so widely without Vollard acting as a conduit of their work to exhibitions (and sales to influential collectors) in Germany, in the United States, in Russia and even in Britain? This is not to argue that modern art would have failed to take hold without the pioneering dealers who first handled it. But the form it took might have been different in its emphases and progression.