I slam was born at the beginning of the seventh century in one of the world’s harshest climates, in Mecca in Saudi Arabia around the year 610 AD, when the Prophet Muhammad began receiving divine revelations from the angel Gabriel. However, it wasn’t until the year 622 AD or 1 AH (after Hijrah, or exile) that the Islamic calendar marks the official start of the religion when, after a dispute with his tribe, the Prophet Muhammad fled Mecca to the city of Yathrib, now known as Medina.

Medina was and still is an oasis in the desert, but though there was water, there wouldn’t have been much variety available to the early Muslims in terms of food, and their diet was mainly limited to dates from the palm trees growing in the oasis; meat and dairy from their flocks of sheep, camel, and goat; and bread from grain they either grew or imported in their trade caravans from the fertile countries of the Levant and beyond. The Prophet’s favorite meal is said to have been tharid, a composite dish made of layers of dry bread topped with a stew of meat and vegetables, which still exists in one form or another, under different names, throughout the Middle East and North Africa, and even as far as Indonesia, where some curries are served over roti.

The Arabs have always been great traders, from even before the advent of Islam. They controlled lucrative trade routes along the Silk Road, and in the early days of Islam, they spread their religion not only through war conquests but also by peacefully converting the people they traded with. The goods they traded included spices as well as dry ingredients such as rice and legumes, although it is unlikely that they traded any fresh produce given how long the camel caravans took to cross the desert from lands where fruits and vegetables grew in abundance.

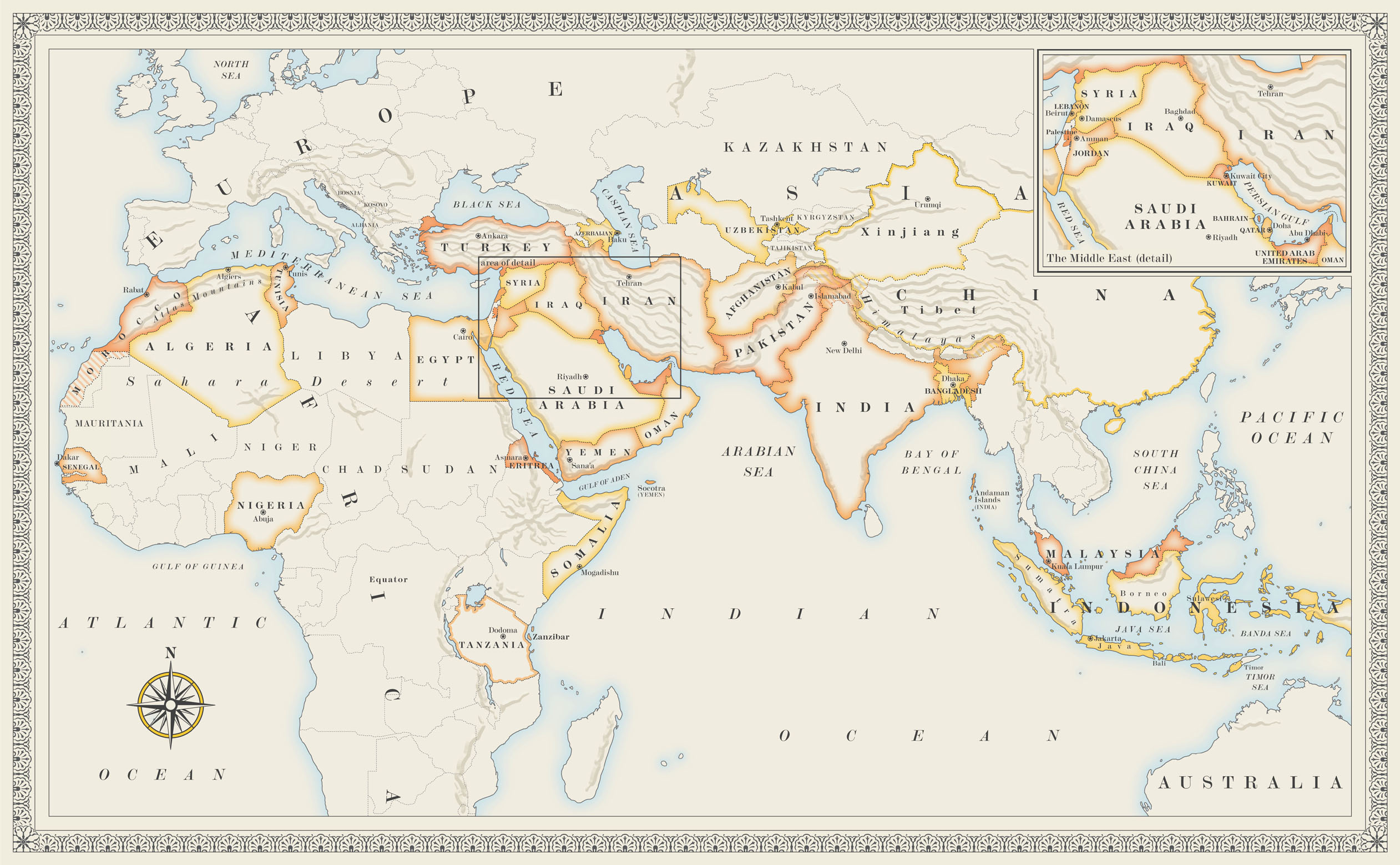

Even today the Muslim world whose recipes I have included follows the same arc more or less as that of the conquests during the expansion of Islam: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Egypt in North Africa, finishing in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India in South Asia, and Xinjiang province and Uzbekistan in Central Asia. In between are Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Jordan, Turkey, and Iran in the Levant; the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar in the Arabian Gulf. On the fringes are countries where the influences are more diffuse, such as Zanzibar, Somalia, Senegal, Nigeria, Malaysia, and Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country.

After the Prophet Muhammad died in 632, the Rashidun (wise guides) established a caliphate, with Medina as its capital, to continue spreading the Prophet’s word. They took Islam to the Levant and North Africa to the west and Persia, Afghanistan, and Iraq to the east, but it wasn’t until the Ummayads founded their own dynasty (661–750 AD), moving the capital to Damascus in Syria, that Muslims began to live in splendor. They expanded their culinary repertoire because of easy access to more varied produce—part of Syria is desert but much of the country is fertile with the fruit growing around Damascus famous throughout the Middle East and beyond; as are the pistachio and olive groves around Aleppo. The Muslims also acquired new culinary knowledge from the locals they ruled over, which they absorbed into their own cuisine.

The Ummayads established one of the largest empires the world had yet seen, continuing Islamic conquests further west onto the Iberian peninsula, and east into Central Asia to create the fifth-largest contiguous empire ever. However, it wasn’t until the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258 and 1261–1517), when the capital moved to Baghdad, that Muslims started to develop a rich culinary tradition.

The Abbasid caliphs favored Persian chefs—the Persians already had splendid courts and a rich culinary tradition—who brought a whole new culinary knowledge with them, which they then adapted to the taste of their new masters.

Food became an important element of Abbasid culture and, in the tenth century, a scribe named Abu Muhammad ibn Sayyar wrote the first Arab cookbook, Kitab al-Tabikh (The Book of Cooking) for an unnamed patron who may have been Saif al-Dawlah al-Hamdani, a cultivated prince of Aleppo. The book contained a collection of recipes from the court of ninth-century Baghdad. The scribe himself descended from the old Muslim aristocracy and, as such, he was in a good position to faithfully transcribe the court’s recipes, which he gleaned from the personal collection of individual caliphs, such as al-Mahdi, who died in 785 AD, and al-Mutawakkil, who died in 861 AD, among others.

Many of the dishes that are today typically associated with Arab, Persian, or North African cooking, such as hummus, tabbouleh, kibbeh, baklava, pilaf, or couscous, do not appear in this book. Still, there are dishes from that time such as hariisah (meat and grain “porridge”) or qataa’if (pancakes folded over a filling of nuts, fried, and dipped in syrup) that are prepared today even if slightly differently and with different names. The medieval lavish use of herbs continues to this day.

The Abbasids allowed several autonomous caliphates like the Fatimids in the Maghreb and Egypt and the Seljuks in Turkey to prosper, and each developed its own distinct cuisine based on local know-how and ingredients, but all remained rooted in the tradition of Persian cooking. It was also during the reign of the Abbasids that Sufism rose as a mystical trend with a particular emphasis on the kitchen as a place of spiritual development.

The next great Muslim empire was that of the Ottomans (1299–1922/1923) who established Istanbul as the capital; and with them, a new culinary influence was born. Ottoman cooks introduced many innovations and were among the first to quickly adopt New World ingredients.

They took inspiration from the different regional cuisines of the empire, which they refined in the Topkapi Palace kitchens in Istanbul where hundreds of chefs cooked for up to four thousand people. Each group of chefs concentrated on one specialty with some groups, like the sweets-makers, having their own separate kitchens. All the chefs were hired on the basis of one test, which was how well they cooked rice, a simple task but a good indicator of skill. Eventually, the Ottoman palace cuisine filtered to the population during Ramadan events when food from the palace was distributed to the poor, and through the cooking in the yalis of the pashas, which was directly influenced by palace cooking.

The Mughals were the last great Muslim dynasty and, at the height of their reign in the seventeenth century, their empire spread over large parts of the Indian subcontinent and Afghanistan. The Mughal emperors belonged to the Timurid dynasty, direct descendants of both Genghis Khan and Timur. The former in particular was famous for his pitiless conquests, destroying conquered cities such as Damascus and Baghdad, with mass slaughter of the citizens. But the Mughals founded a refined dynasty that owed a debt to Persian culture. This was evident in their art and literature and in their cooking, which they made their own by using local ingredients and techniques, and using an impressive number of spices, which they almost always toasted before use.

The recipes I have included in this book are mostly from countries where these three great culinary traditions have developed. There are more than three hundred recipes, but even with this number, I have had to limit the selection to classics as well as personal favorites. For a comprehensive selection, I would have needed more than one volume. And I have divided the book into chapters concentrating on ingredients or types of food that are essential to the foods of Islam, with the two largest chapters devoted to the two main staples of the Muslim world—bread and rice.

THE DATE

The date is the most important fruit in Islam. It was important in the early days of Islam and it remains important today, at least in the parts of the Islamic world where it grows, which is mainly the Middle East and North Africa. In many places, the date palm is known as the tree of trees, also known as “the mother and aunt of Arabs,” as their lives depended on it. Long before oil riches, dates were the main staple of Gulf Arabs, both in terms of diet and trade (the date palm sap is used to make palm sugar), as well as construction (its wood, although not very hard, is used in building), and they were also Gulf Arabs’ main sustenance along with bread, meat, and milk. Dates were a commodity used to barter with neighboring tribes.

It is not easy to pinpoint the exact origins of the date palm. According to one myth, the tree was first planted in Medina by the descendants of Noah after the Flood. But if not in Medina, then in an equally hot place with plenty of water. As the Arabs say: “The date palm needs its feet in water and its head in the fire of the sky.” It is therefore probable that the date palm first appeared in the oases of the Arabian desert. And that is still where most date palms are grown. Saudi Arabia is the second largest grower in the world after Iraq, and the Saudi’s coat of arms is a date palm over crossed swords.

The date palm is also grown on the coasts of Africa, in Spain—in the east, a reminder of the time of Muslim rule—in western Asia, and in California. The soldiers of Alexander the Great are said to have introduced it to northern India by spitting the pits from their date ration around the camp, so that, over the course of time, palm groves grew there.

There are three main types of date: soft, hard, and semi-dry. The semi-dry is most popular in the West, commonly sold in long boxes with a plastic stem between the rows of fruit as they do in Tunisia. Soft dates are grown in the Middle East mainly to eat fresh, although they are also dried and compressed into blocks to be used in a range of sweets. As for hard dates, also called camel dates, they are dry and fibrous even when fresh. When dried, they become extremely hard and sweet and keep for years. They remain the staple food of Arab nomads.

The fruit goes through different stages of ripening, with each stage described by an Arabic term that is used universally in all languages. Khalal describes the date when it is full size and has taken on its characteristic color depending on the variety—red or orange for Deglet Noor, dull yellow for Halawi, greenish for Khadrawi, yellow for Zahidi, and rich brown for Medjool. Rutab is the stage at which the fruit softens considerably and becomes darker, and tamr is when it is fully dry and ready for packing.

The date still figures prominently in the diet of Gulf Arabs. It is the first food people eat when they break the long day’s fast during the month of Ramadan, the tradition being to eat only three, to emulate the Prophet Muhammad who broke his fast with three dates. The date’s high sugar content makes it an ideal breakfast after so many hours without any food or water, supplying the necessary rush of energy while being easy on the empty stomach. Some people eat it plain, others dip it in tahini, and others have it with yogurt or cheese, and particularly a homemade curd called yiggit.

The date also features prominently in the Gulf Arabs’ regular diet, both in savory and sweet dishes; and date syrup is used to make a drink called jellab, which is sold on the street packed with crushed ice and garnished with pine nuts and golden raisins.

RAMADAN AND OTHER IMPORTANT OCCASIONS IN ISLAM

From the birth of a child to the circumcision of boys to marriage to burying the dead, every occasion in Islam is marked with special dishes that celebrate, commemorate, or comfort, as the case may be.

The month of Ramadan is the most important time of the year for Muslims, a time for fasting and feasting when Muslims throughout the world change their ways to show their devotion to God. No food or drink is allowed to pass their lips from sunrise to sundown, but as soon as the sun sets, people gather with family and friends to break their fast, whether at home or in restaurants and cafés, or simply on the street if they happen to be working and have nowhere to go to break the fast. The menu changes according to where you are. In the Arabian Gulf the fast is first broken with dates and water before moving on to the main meal, known in Arabic as iftar. Then people pray before sitting at the table to partake of their first meal of the day. In the Levant, people break their fast with apricot leather juice, fattoush (a mixed herb and bread salad), and/or lentil soup. In the Maghreb, soup is the first thing people eat after sunset, whereas in Indonesia they break their fast (called buka puasa there) with sweet snacks and drinks known as takjil. During Ramadan, Indonesian restaurants serve their whole menu at each table and charge diners only for the dishes they consume before taking away those that remain untouched to stack them again in the restaurant window.

Lailat al-Bara’a (the night of innocence), on 15 Sha’ban, is the night of the full moon preceding the beginning of Ramadan, when sins are forgiven and fates are determined for the year ahead and when mosques are illuminated and special sweets are distributed.

The two main feasts in Islam are Eid el-Fitr (the feast of breaking the fast), which celebrates the end of Ramadan, and Eid al-Adha (the feast of the sacrifice), which signals the end of Hajj (Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca) and is the most important festival in Islam. Eid al-Adha is also known as Baqri-Eid (the “Cow Festival”) because its most important feature is the sacrifice of an animal in commemoration of the ram sacrificed by Abraham in place of his son. In Muhammad’s time, a camel normally would have been sacrificed.

Ashura, which falls on the tenth day of the month of Muharram (which means “forbidden”), is a time of mourning for Shi’ite Muslims to commemorate the massacre of Muhammad’s grandson Hussain and his band of followers at Karbala. A perfect place to witness the rituals associated with Ashura is Iran, which is predominantly Shi’ite, as well as South Lebanon, the stronghold of Shi’ite Hezbollah (the party of God). Most Shi’ites follow the ancient Persian tradition of nazr (distributing free foods among the people) and cook nazri (charity food) during the month.

Turkey is one of the places to witness the holy nights called kandili: Mevlid Kandili (the birth of Prophet Muhammad), Regaip Kandili (the beginning of the pregnancy of Prophet Muhammad’s mother), Miraç Kandili (Prophet Muhammad’s ascension into heaven and into the presence of God), Berat Kandili (when the Qur’an was made available to the Muslims in its entirety), and Kadir Gecesi (the Qur’an’s first appearance to Prophet Muhammad). The word kandil (from the Arabic kindil) means candle in Turkish, and some trace the application of this word to the five holy nights back in the reign of the Ottoman sultan Selim II (1566–1574) who gave orders to light up the minarets of the mosques for these occasions.

Saints’ days are also widely observed in the Muslim world, but the two Eids and the holy nights are the great festivals, and they are the only ones universally observed by all Muslims without any question as to the worthiness of the occasion.

And there are of course the celebrations for important life occasions such as circumcision and marriage, with rich Gulf Arabs roasting whole baby camels for weddings while Moroccans prepare lavish feasts called diffa (hospitality) where pretty much the whole of the Moroccan repertoire is served, starting with b’stilla, a sweet-savory pigeon pie, and finishing with a seven-vegetable couscous to make sure no guest is left hungry. In between are the mechoui (whole roasted lamb), a selection of tagines (both savory and sweet-savory), and salads. Moroccan and Indian weddings last up to three days, although the latter can, in some cases, last up to a week, with biryani, a multilayered rice dish, taking pride of place at the wedding buffet, in particular on the night of the wedding.

I had planned to devote a separate chapter to celebratory dishes, but I feared this would be repetitive, not to mention confusing. Instead, I single out these dishes in the chapters they belong to, explaining in the headnote which special occasion they are associated with.