3 Sources of Crowth

The friends of [Harriman’s] youth describe him as frank, open, fond of gaiety and fun. The twenty-odd years of the Stock Exchange had effectually removed the frankness and the openness. In their place he had a studied reserve, a careful holding of himself in leash, a fixed resolve that no man should be able to guess the real thoughts and motives that lay within his mind.

—C. M. Keys, “Harriman: The Man in the Making”

Railroads were the obvious arena for a man of ambition in the 1880s. As the largest and most dynamic industry in the nation, they were the catalyst for an industrial revolution that was transforming American life with bewildering speed. More track would be laid during the 1880s than in any other decade. Expansion wars of unparalleled ferocity raged well into the depression of the 1890s, giving rise to the systems that would dominate the railroad scene for much of the next century. A man entering the field during these years could find himself overwhelmed and confused by the sheer rush of events, as if he had wandered unexpectedly into the swirl of a vast and desperate battle.

For a man of uncommon intelligence and clarity of vision, however, the panorama unfolding before his watchful eyes offered a classroom of exceptional value. Anyone who learned the correct lessons there would be well prepared for the conditions that followed. Like Wall Street, where the industry’s roots ran deep, the railroad arena was no place for the timid or unwary. The challenges were great, the risks even greater. In one sense at least they were inescapable for Harriman. As a broker he had little choice but to learn the intricacies of rail securities because they were the lifeblood of the New York Stock Exchange.

The exchange accepted its first rail stock in 1830 and then watched the list mushroom. By 1885 it contained 125 railroad issues compared to only 26 nonrail stocks. Railroad bonds also dominated that market, where they competed only with state and federal securities. The orgy of mergers that would create a new breed of industrial securities was still a decade away, the utilities even further in the future. With the list so top-heavy in one area, no broker could afford to be less than expert in rail issues.1

But railroad securities were not the same thing as railroads. Dealing in the one did not provide an education or even insight into the other unless one sought it out. In Henry’s case the opportunity first arose when William Averell put him on the board of the Ogdensburg 8c Lake Champlain, a 118-mile road running between Ogdensburg and Rouse’s Point on Lake Champlain, just below the Canadian border. The position was not merely a gesture; Averell needed Henry’s financial expertise and saw a way to give him some business as well.

Henry was not the only new director in June 1879. He was joined by Stuyve-sant Fish, who came from an old and socially prominent family connected to the Harrimans through the Neilsons. His father, Hamilton Fish, had served New York as governor and senator before becoming secretary of state under Ulysses S. Grant. His mother was a descendant of William Livingston, the first governor of New Jersey. When Henry first met Fish is unknown. The families had known each other for years, and Henry may well have met Fish socially through the Neilsons or Livingstons. Certainly he knew him from Wall Street, where Fish worked for Morton, Bliss 8c Company. No association was to have a more profound influence on Harriman’s life.2

The contrast between them could not have been more striking. Three years younger than Harriman, Fish had grown up with every advantage. As a boy he was educated in the best private schools and lived two years in Europe with his family. He followed his father to Columbia, but his mind turned to business rather than politics or the professions. After graduating in 1871, Fish worked briefly for the Illinois Central Railroad, then entered a position awaiting him at Morton, Bliss. Tall and blond, a genial giant whose blue eyes and heavy features spread easily into a smile, Fish had a pleasant manner born of social assurance. At work, however, he could be a martinet.3

By 1877 Fish had decided that his future lay in railroads rather than banking. He left Morton, Bliss that March to join the board of the Illinois Central, where he remained for nearly thirty years until ousted by his old friend Harriman. The company had just made the pivotal decision to buy the bankrupt connecting lines between the Ohio River and New Orleans and reorganize them into the Chicago, St. Louis 8c New Orleans Railroad. Since Fish handled financial matters for the New Orleans road, he needed friendly firms to sell securities, arrange loans, and take care of other needs. Harriman was a logical man to use, given the long family association, their circle of mutual friends, and Henry’s reputation for conservatism.4

By the late 1870s Fish was throwing some business Henry’s way and had already cast his lot with the railroad industry while Harriman’still pondered his future. During the next few years Fish provided the model if not the inspiration for Henry’s own change of career. The fact that Fish turned up on the Ogdensburg board with Henry in June 1879 indicates clearly that they were looking to expand their mutual interests. Fish had no connection to the road other than through Henry, who had been put there by his father-in-law. Here was the classic tiny acorn that was destined to yield a mighty oak. From this first modest venture together Fish and Harriman learned that they made a good team in certain respects.

The Ogdensburg had a peculiar history that previewed the pattern of so many later western roads. Chartered in 1845 as the Northern Railroad of New York, it was promoted as the last link in a chain of roads running from Boston north to Montreal and west to Lake Ontario. Five years later the road opened to a chorus of enthusiasts predicting a vast flow of traffic away from New York City to Boston via the northern route. But the vast flow never materialized. Twice before the Civil War the road failed and was reorganized. In 1876 the hapless line slid back into bankruptcy again, and William Averell became its receiver.5

Averell had been on the board since 1873 and knew just how dismal the road's prospects were. Net earnings had tumbled 42 percent between 1870 and 1876. The road needed new rails and equipment, and its capital structure was saddled with bonds and preferred stock that paid 8 percent. Averell managed to take the line out of receivership in April 1877 and became its president a year later, but the road continued to flounder. He needed a fresh infusion of capital to revitalize the road just as he was about to acquire a new son-in-law who worked in the money market. Harriman was put on the board to help raise money and restructure the company; he brought with him Fish as a friend who commanded wide resources.6

By the end of 1880 Harriman and Fish had put together a plan to refund the existing bonds at a lower rate of interest. This was Harriman’s first stab at the kind of restructuring that later became his trademark, and it had little effect. Money was spent to improve the Ogdensburg, but it faced a future with too few options. In 1881 Harriman and Fish left the board, having made their imprint on the road's finances but not its future. Five years later the road was leased to the Central Vermont, which had acquired control of its stock.7

What had Harriman learned from this first venture into railroads? Probably not much, other than getting his feet wet. That same summer of 1881 he and Fish turned their attention to a more promising opportunity. The Sodus Bay & Southern was a small road running from Sodus Bay, a harbor on Lake Ontario midway between Oswego and Rochester, to the town of Stanley thirty-four miles to the south. It too was a derelict of grand schemes gone unfulfilled. The road opened in January 1873 just in time to catch the depression and went into receivership a year later.8

The receiver was Sylvanus J. Macy, a shrewd New Yorker with impeccable business credentials. His grandfather Josiah Macy had built a flourishing oil business in New York, and his father, William, also served as president of Seamen’s Bank. The Macys were Quakers with a reputation for shrewdness and integrity. In the spring of 1872 the Macys sold their company to Standard Oil; a few months later William Macy died, leaving Sylvanus and his brothers a large estate. The firm of Macy & Sons continued to prosper. By 1874 Sylvanus had become a senior partner and was thought the richest of them.9

Something attracted Sylvanus to the town of Sodus Point and its railroad. He bought a large block of the road's bonds and went to Sodus Point, where he astonished the locals by buying real estate and putting up buildings out of his own pocket. In September 1875 he helped reorganize the railroad as the Ontario Southern; fifteen months later he left Macy 8c Sons to concentrate on Sodus Point. He became a presence in the little town, a leading citizen and driving force in its economy. But he could not make the railroad go. The line still failed to earn even its expenses, let alone pay interest or dividends.10

In December 1879, Macy and the other major bondholders surrendered the road to a fresh group of optimists who projected an extension toward the bituminous mines in Potter County, Pennsylvania. But the scheme flopped. Despite the return of good times, the wretched line ran only one train a day each way and barely earned expenses. The discouraged Macy moved to Rochester in 1881, but that October he formed a syndicate to buy back the original thirty-four-mile road. This time his partners included Harriman and Fish.11

Here was another of those countless small lines destined for the graveyard of lost dreams, where a plot had already been reserved for it until a quirk of fate brought it to Harriman’s attention. Apparently Mary’s brother William Averell, who lived in Rochester, had invested in the Sodus Bay; possibly some other relatives had too. Uneasy over the prospect of losing their money, they asked Harriman to look into the road's affairs.12

This was the story Harriman told years later, and it fits the circumstances well. All his life Henry was obliged to bail out family or friends who had made unwise investments. But he also had a way of arranging his past to suit him when confiding it to others, and he may have done just that with the rest of the story. Legend has elevated this episode into the moment of epiphany for Harrimans future career, and his own words reinforced that status. “It was a lesson for me that I followed in after life,” he said later, “that the only way to make a good property valuable is to put it in the best possible condition to do business.”13

Kennan’swallowed this version whole, but the known facts, though sketchy and contradictory, do more to deny than confirm. For one thing, the road was not a good property but a proven dog. Harriman in his prime could not turn a sows ear into a silk purse, and he was still an acolyte in 1881. For another, there is no solid evidence that he was the decisive factor in bailing the road out. He may have devised what proved to be the winning strategy—or it might have been Fish—but Macy remained the main man in the property.

In October 1881 Henry became vice-president of the road with Macy as president. For the first time Harriman was an officer of a railroad, but Macy remained head of the syndicate. He also joined with Macy, Fish, and R. Fulton Cutting in erecting a grain elevator at Sodus Point in hopes of reaping a profit from the lake traffic to come. In this venture, too, Macy remained the largest owner. During 1882 the syndicate reorganized the road as the Sodus Bay & Southern, cut the stock and bonds nearly in half, and refunded the bonds at a lower interest rate. Still the road failed to earn even its expenses. At this point, according to legend, Harriman came up with a brainstorm. He bought out his discouraged partners, then plowed money into improvements and sold the road to the Pennsylvania for a handsome profit.14

Particles of truth are sprinkled through this legend. Someone saw what eluded the other syndicate partners: the road’s chief (and perhaps only) asset was its potential as a pawn on the chessboard of rail strategy. The Pennsylvania Railroad lacked an outlet on Lake Ontario while its most bitter rival, the New York Central, touched the lake at several points. The Pennsylvania did not want to be shut out of lake traffic, and the New York Central did not want the Pennsylvania to gain access to the lake. If Henry could play on the mutual fears of these rivals, he might unload the road on one of them at a hefty price. Packaged properly, the tiny Sodus Bay could become the object of a bidding war between the two richest railroads on the continent.

According to the legend, Henry made his move in October 1883 by offering either to sell his own shares or buy those of the other syndicate members at a price he named. There were only twelve stockholders; several jumped at the chance to get out, and Harriman found himself in possession of his first railroad even if it was shared with his friends. He organized a board that included his brother Willie, Fish, Macy, and Mary’s brother William. “I soon recognized that if I wanted to dispose of this property,” he said years later, “I would have to put it in good shape so that the rival lines at each end of my road would want to purchase it.”15

From this sprang another myth of the Sodus Bay as the experience that taught Harriman the lesson of spending for improvements as the key to making money on railroads. But the evidence tells a different tale. Harriman held the road only nine months before selling it, hardly enough time to overhaul even a small line. During that time there is no record of funds spent for improvements or indication of work done. The only sharp increase in expenditures came after the Pennsylvania took control. Nor did Harriman replace Macy, who remained president until the road was sold.16

Harriman and his friends did manage to drum up more business. In 1883 the Sodus Bay hauled nearly twice the tonnage it had carried two years earlier and half again as many passengers. The new business produced the largest gross earnings the road had seen since the depression and its first modest surplus because none of it went for improvements. In 1884 the road was still laid with its original fifty-six-pound rail. It also had the same rolling stock as when it opened for business in 1873 except for one more locomotive, a new baggage car, and forty-eight fewer freight cars. If Harriman bought any new equipment (and there is no evidence that he did), he did not expand the fleet. The locomotives in 1884 were of the same weight as those running in 1880.17

Harriman did bring in a new superintendent to improve operations and drive the business, but he invested little money in the road. Maintenance outlays under Harriman were only 24 percent of earnings compared with 39 percent in 1881 and 38 percent in 1879. The road did spend more on repairs to engines and cars during those months than for any year since the depression. This suggests that, far from upgrading the road and rolling stock, Harriman was trying to hold the old equipment together long enough to unload the property.18

The Sodus Bay under Harriman looked very much like the same old derelict, except that in 1884 it actually earned $8,726 more than its expenses, by far its best performance. Henry managed this profit not with a program of improvements but with the tried-and-true tactic of skimping on upkeep. The object was to create the appearance of improved performance as an inducement for buyers. In short, the Sodus Bay experience looks less like Harriman’s moment of revelation than like a financial campaign managed with impressive skill for maximum profit. It also reveals his willingness to recast his image in a likeness he preferred.19

Once business picked up, Harriman dangled the Sodus Bay before the two rival giants, telling Frank Thomson of the Pennsylvania that his system needed an outlet on the lake and officials of the New York Central that they could not afford to let the Pennsylvania acquire the road. This simple tactic was effective in an industry where roads nearly always justified expansion in defensive terms and officers lived in mortal terror that rival lines would steal a march on them. The Central paid willingly for an option on the Sodus Bay until its agents could investigate the road. Frank Thomson then offered to buy the road outright only to learn that he was blocked by the Central’s option.20

The option expired at noon on July 1. The Central waited until that morning before sending an official to Harrimans office to get the option renewed. Henry already had a good offer in hand from the Pennsylvania, however, and stayed away from his office all morning. When the option expired, he telegraphed Thomson that the road was his. After cleaning up some legal problems over right-of-way, Henry took his pay in Pennsylvania Railroad bonds and walked away with a tidy profit for himself and his friends. Later he bought control of the grain elevator at Sodus as well, and the hard times of 1894 found him scrounging for wheat to fill it.21

The most important result of these early forays into railroads was not the education of E. H. Harriman; rather, it was the success of his collaboration with Fish, which tightened a business association that thrust Harriman into the arena he was destined to conquer. In a sense Fish not only arranged for Henry’s education in railroads but also provided him with a scholarship to a much larger campus where his learning experience truly commenced.

No western railroad owned a better reputation than the Illinois Central. It was the bluest of blue chips in a region where the ledgers of many roads bled a steady stream of red. Completed in 1856, it was the first land-grant railroad and at 705 miles the longest railroad in the world. It was also an anomaly, the only major north-south line in a nation where overland transportation flowed east-west. On a map the Illinois Central resembled a “Y” with one arm anchored in Chicago and the other stretching to Dunleith in the northwest corner of Illinois. The arms joined just above Centralia, and the stem ran southward to Cairo on the Ohio River.

After the Civil War the Illinois Central expanded in two directions. It joined the railroad frenzy in Iowa by leasing some small roads extending from Dunleith to Sioux City on the Missouri River. This line gave the Illinois Central a modest share of the east-west traffic between the rivers. It also won a lengthy battle to acquire the roads reaching from the Ohio River to New Orleans. Once perfected, this addition would give the Illinois Central a through line from the lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.22

By 1880 the system embraced 1,320 miles and carried a diversified traffic that made it an impressive cash cow paying regular dividends through the depression of the 1870s. Analysts heaped praise on what one called “the conservative spirit so dominant in the company’s affairs.” The management was honest, capable, and dedicated to keeping the debt low; in 1880 the company had outstanding only $29 million in stock and a paltry $12 million in bonds. The operation was efficient and maintenance standards high. Since 1877 the company had invested heavily in improvements, upgrading the new lines in Iowa and south of the Ohio River to the same standard as the parent road. Earnings remained remarkably stable through the lean 1870s, thanks to general manager James C. Clarke’s careful husbanding of resources.23

The management regarded its conservative reputation as a badge of honor. But as the competitive environment exploded into an orgy of expansion, pressure mounted on every major road to rethink its strategy. This debate split the Illinois Central board in predictable fashion. One faction clung doggedly to the ways of the past, believing as so many businessmen do that the old formula for success would continue to work regardless of changing conditions. Another group argued that the company could not afford to stand still or more aggressive systems would swallow it.

As the depression wound down, the traditionalists still dominated the management. The revolution that was about to transform American railroads into giant systems was a speck on the horizon, visible only to the most acute eyes. Its approach infiltrated the boardrooms of every major road, triggering debates over policy that often led to turmoil and turnover of managements, yet few rail executives understood what was happening. It was as if they were victims of a spreading epidemic and helpless to diagnose its nature or find a cure.

Stuyvesant Fish returned to the Illinois Central in 1877, just as this debate over the company’s future was taking shape. A new president, William K. Ackerman, was chosen that October, and James C. Clarke was promoted to Ackermans old post of first vice-president. The two men complemented each other well. Ackerman was a meticulous, scholarly man who had spent his entire career in the business office, while Clarke was a lifelong railroader with a gruff, profane manner that endeared him to the men he commanded. Although cautious and careful by nature, both men were convinced the Illinois Central had to expand if it were to remain prosperous.24

It was from Ackerman and Clarke that Fish gleaned much of his education in railroads and probably his point of view as well. Gradually he emerged as the leading advocate of progressive policy on the board, a strong voice growing stronger as his confidence increased. In effect, he blazed the trail Harriman later followed, joining the board as a young financier and transforming himself into a railroad manager.

As the depression lifted, two basic issues confronted the Illinois Central board: expansion and internal reorganization. Although the decision to extend to New Orleans had been made in 1872, the long struggle to gain control of the southern lines had not reconciled some of the conservatives to taking them over. The moves south and into Iowa made them uneasy because of the costs and extended obligations involved. While conceding the need to keep the system in top shape, they balked at anything that might jeopardize the roads proud dividend record. So too did they resist the notion that the company’s management structure needed revamping. Every action met with resistance, every vote was divided, and the officers felt the strain.25

Through these conflicts Fish grew in both knowledge and stature, steadily extending his influence until he emerged as the leader of those directors favoring more aggressive policies. But he did not have a majority with him, and the board split badly on most crucial votes. Much depended on how heavy a financial burden the new lines proved to be. This problem opened a door for Fish. If he could find creative ways of handling these obligations, he might disarm the fears of the conservatives. The logical man to help him do this was his friend Harriman.

In June 1881 the Illinois Central was looking to sell some bonds issued by its New Orleans line. Probably at the urging of Fish, E. H. Harriman & Co. bid on the $2.5 million lot and got them along with an option for another $1.5 million. This first transaction with the Illinois Central proved fateful for Harriman in two respects. It launched his brokerage on a course away from general commission business and toward a deeper involvement in railroad finance, and it set in motion the chain of events that lured Harriman away from banking into railroading.26

This first venture turned out to be anything but routine. Just before Harriman received the bonds, a crazed office-seeker shot President James A. Garfield. The markets plunged sharply and then twitched uneasily until Garfield’s death on September 19. After a difficult struggle, Harriman managed to unload the bonds in a depressed market. Although legend insists that Harriman profited handsomely from this transaction, no one knows how much he actually made. What he did make was a reputation for reliability, which proved far more lucrative in the long run. With Fish’s blessing, he got involved in the road’s financial affairs, hoping to become its American agent.27

Fish had more than friendship in mind. With the clash over policy heating up, he was looking for allies to help him gain control of the board. Among the twelve directors he had only two consistent allies, his old friend W. Bayard Cutting and John Elliott. Ackerman and Clarke sided with Fish on most policy matters but had to hew a careful course because of their positions as officers. To complicate matters, the board held staggered elections in which only three directors stood for election each year.28

Disagreement still raged over what to do with the New Orleans line. Clarke, who had managed it since 1877, argued repeatedly that it should be upgraded and integrated into the Illinois Central system. By 1881 he had accomplished the first goal, but it took another year to gain approval for a perpetual lease of the New Orleans road. Fish and Clarke then pressed hard for vigorous expansion south of Cairo to stake out territory before competitors grabbed it. The company was also constructing branches in the north and grappling with the Iowa lines as well. The scale of this expansion alarmed some directors, who fretted over how the board could pay for it, let alone manage things coherently.29

Fish concluded that an enlarged system required a new management structure, preferably one with himself in charge. While agonizing over expansion policy, the board also created a committee to tackle the problem of reorganization. With the president and vice-president located in Chicago and the financial office in New York, there had long been friction over who held what responsibilities in the latter office. In November 1882 the committee unveiled a plan with two key changes: Clarke would become first vice-president and chairman of the executive committee, while Fish would assume the new position of second vice-president. Fish got his new post, but Clarke wanted no part of the intrigues in New York. He agreed to stay only after the board let him remain in Chicago with title of first vice-president and general manager.30

By 1883, then, the Illinois Central found itself at a crisis in its history. While analysts praised its prudent management, turmoil rocked its boardroom. During this year Fish reached a fateful decision: the solution was to replace the old guard on the board with his own social and business friends, who would support the policies he advocated. Every new vacancy on the board became for Fish an opportunity to elect an ally. The death of one director enabled him to bring aboard Sidney Webster; his next recruit was Harriman.31

Henry was happy to comply. His short association with the Illinois Central had been profitable and looked to be more so. Whether he saw anything more in it at this early stage remains doubtful. By 1883 he and Fish had wrapped up their Ogdensburg road project and were deep into the Sodus Bay venture. He was a natural ally for Fish’s larger ambitions on the Illinois Central, and the more prominent Fish grew in the company, the more likely it was that Henry’s firm would become its financial agent. Dutch interests owned a large amount of Illinois Central stock and entrusted most of it to Boissevain Brothers, which in turn used American agents. Harriman persuaded them to use his firm.32

As the election approached, Fish rounded up proxies for a ticket that included Harriman in place of one of the old directors. Henry had no trouble getting his seat, but the election of officers took an unexpected turn. Ackerman shocked the board by declining to serve and suggesting that Clarke take his place. Thrown into confusion, the board postponed the election a month, then reluctantly took his advice, leaving Fish as the lone vice-president.33

Suddenly the takeover envisioned by Fish seemed on the verge of reality. As president, Clarke was strictly an operations man who took his cue on policy matters from Fish. With Harriman on the board, Fish had a valuable ally and conduit to the money market. All he needed was one or two more loyal directors to complete his coup. In December 1883 he had Harriman move creation of a committee to look anew at the organization in New York. The motion had two objectives: to place the New York office firmly under the vice-president’s control and to raise the salaries of officers there.34

The first point made good sense with Clarke residing in Chicago. Harriman and Sidney Webster made up a majority of the committee; the third member was Frederick Sturges, a longtime director who opposed their views and submitted his own minority report. At the decisive board meeting Harriman and Webster carried their recommendations by narrow margins. Fish was given command of the New York office force and a hike in salary along with the secretary and treasurer.35

This clash marked the opening of a power struggle that raged for three years as Fish and Harriman fought to oust the old-timers who opposed their policies. Sturges was the first to go. Indignant over his defeat and upset at the direction the company was heading, he resigned despite pleas that he stay. The tug of disagreement in boardrooms was gentlemanly but no less grim or serious for its civility. “I am sorry that there is any difference among the Directors,” sighed Clarke to Fish. “I should greatly regret to see any difference arise that might lead to any estrangement or that want of harmony and co-operation which is so essentially necessary in the successful operation of a great Railroad.”36

Fish also regretted the want of harmony and moved to restore it by replacing dissonant voices with others more in tune with his own. Another old-timer, treasurer L. V. F. Randolph, also stepped down as a director, and Ackermans seat was still empty, giving Fish three vacancies on the board. He brought in banker Walther Luttgen of August Belmont & Co. (a friend of Harriman’s) and two society friends, Robert Goelet and S. Van Rensselaer Cruger. Although Cutting was an ally of Fish's, he could not reconcile himself to the Sturges incident and resigned as director a month after the election. Fish replaced him with William Waldorf Astor.37

Analysts were quick to sense what was happening. One called attention to a lack of the “conservative spirit so long dominant in the company’s affairs” and linked it to “rumors connected with some of the late changes in management.” Sam Sloan, a crusty old railroad man who was a neighbor of both Fish and W. H. Osborn, the grand old man of Illinois Central, minced no words in his assessment. “I don’t like that Harriman,” he growled. “He and ‘Stuyv’ Fish are going to get Osborne [sic] in trouble with the Illinois Central, if he don’t look out.”38

How much of the change was Fish and how much was Harriman is not clear, but there is no doubt that Fish led and Harriman followed. Having solidified his hold on the board, Fish got another raise in salary on a motion put forth by his friend Henry. When Randolph retired as treasurer, Fish took over his office as well with another hike in pay to $12,000. Harriman got his reward in the form of more bonds to sell.39

Fish needed the money despite his own personal wealth because he was being dragged into a very expensive lifestyle. His wife Marian (or Mamie) liked to refer to Fish as “The Good Man” in the old Knickerbocker style, but there was nothing old-fashioned about her. A bright, strong-willed woman as chatty as Fish was silent, she had plunged with gusto into the rapidly escalating arms race of New York and Newport society. The Fishes had a fine house on East 78th Street in New York, a Stanford White creation with one of the largest ballrooms in a private residence, and a Newport estate called Crossways, where Mamie entertained lavishly.40

The place Fish liked best, however, was Glenclyffe Farms, his country place at Garrison. He had always been proud of his lineage through an old Puritan family stretching back to the Mayflower. The simple, austere character of his ancestors appealed deeply to him, as did their strong, silent ways. The “Rosebud” of his soul was no mystery to anyone. At Glenclyffe he liked to haul his guests up the stairs to a plain, old-fashioned bedroom without running water that he and his brother had shared as boys. “None of the maids will sleep in it,” he murmured with a shake of his massive head, “it is not good enough for them; yet I spent some of the happiest hours of my life here.”41

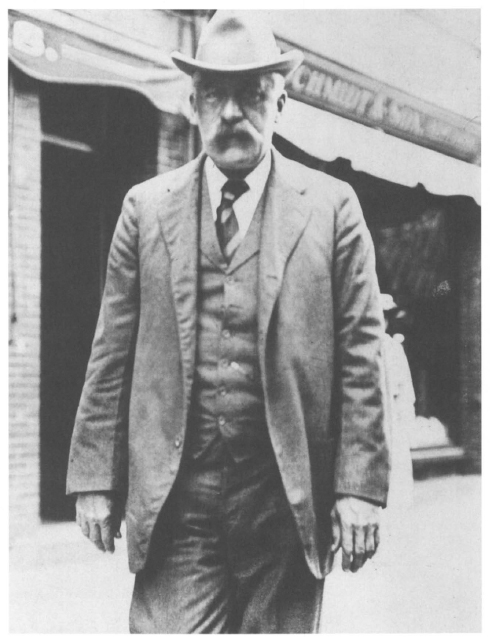

Mentor and friend turned foe: Stuyvesant Fish, who helped launch Harriman’s railroad career and later fought an ugly battle against him. (Culver Pictures)

But he had married Mamie Anthon, whom he adored and who thrived on a very different lifestyle. Fish cared little for society but tolerated its amusements to please his wife. More than once he shuffled wearily home from a business trip to find the house crowded with people who had taken over the place and sometimes even his shaving gear. “It seems I am giving a party,” he would shrug diffidently. “Well, I hope you are all enjoying yourselves.”

Mamie appreciated her husband’s devotion but could not resist teasing him. “Where would he be without me?” she asked in mock innocence. “I put him on the throne.” It was an expensive throne, however, and the cost of extravagance soared at a pace that challenged even Fish’s ample resources. There was no doubt what he needed from the Illinois Central or the investment advice given him by Harriman. The unanswered question was rather, What did Harriman himself want?