8 Going for Broke

The Union Pacific of that day was a melancholy imitation of a railroad. Of the whole system he found only about 400 miles of road that was graded at all, the rest being merely a collection of ties and rails laid down on a dirt foundation. The station buildings were tumble-down shacks. The cars, as he whizzed past them, looked old and battered, and eloquent of economy in the purchase of paint. West of Cheyenne, on the main line of traffic from the Missouri to Ogden, his train climbed hills by the hundred, hills that would compel every heavy freight train to call upon two engines for its haulage. The engines were old and light. Everything was dirty, decrepit, low-class.

—C. M. Keys, “Harriman: The Man in the Making”

Nothing has done more to shape the Harriman legend than the myth that he found the Union Pacific a dilapidated wreck. What better way to demonstrate Harriman’s genius than to portray him as the Merlin whose magic touch transformed a decrepit antique into the very model of a modern railroad? Everyone from journalists to Schiff to Kennan perpetuated this story over the years. Averell Harriman, who was only six years old when his father took charge of the Union Pacific, insisted late in life that “its rusting rails were sinking into mud; its ties were rotted and broken, its rolling stock falling apart.”1

Observers at the time took a different view. Since a bankrupt road did not have to pay interest on its bonds, it could devote most of its earnings to upkeep. The Union Pacific receivers did just that and thereby earned praise from all sides. For two years the Wall Street Journal hammered at the themes that the Union Pacific was well maintained and the stock undervalued. In October 1897, just two months before Harriman joined the board, the Journal issued its most emphatic statement on the roads condition: “Under the receivership the whole property has been put in the most extraordinary fine condition…. It is no secret that instead of buying a worn-out property, the new company will get a system in as fine condition as anything in the West. New rails, new bridges, new rolling stock, passenger and freight, in fact everything that goes to make up a first-class railroad line.”2

Those who knew the Union Pacific from the inside, such as secretary Alex Millar and operating official W. H. Bancroft, scorned the “two streaks of rust” myth and insisted that the road compared favorably with other western lines. Western railroads did not match eastern lines in their physical condition because they were usually longer and carried much less business. Bancroft made clear what he meant by a typical western road: light rails, little or no ballast, heavy grades over mountain ranges, and light equipment.3

The myth erred in two respects: it described the Union Pacific as a rundown road and measured it by the standard of eastern roads. What Harriman found was not a derelict but a typical nineteenth-century western road, old-fashioned in both its equipment and operating procedures.

The task facing Harriman, then, was more subtle than the myth has portrayed. By prevailing standards, the Union Pacific was in decent shape to do what it had done in the past. Most directors and observers, their thinking dulled into caution by hard times, saw this minimum as all that was needed. The long depression had blinded them to the potential for a bonanza from the recovering western economy. But Harriman’s trip west had stirred his mind to a daring conclusion: traffic was there in huge quantities and could be handled only by transforming a tolerable nineteenth-century road into an efficient twentieth-century one.

Harriman was not alone in this vision of what the future held, but he was the only man willing to bet the store on it. He was going for broke on an idea that was not as obvious as it seemed later, and he had somehow to persuade the rest of the board to follow him.

Less than a month after becoming chairman of the executive committee, Harriman’set out to inspect the entire Union Pacific system. He borrowed Fish’s private car from the Illinois Central and put it at the head of a special train consisting of some Union Pacific private cars and a baggage car with the locomotive at the rear. This arrangement provided a nice breeze and allowed Harriman to inspect the roadbed, buildings, equipment, and countryside. For most of the trip the train ran only in daylight because Harriman wished to see everything.

On any excursion Harriman had an inimitable way of mixing business with pleasure. He took along the five Union Pacific officers who had the most to tell him: president Horace Burt, chief engineer J. B. Berry, general manager Edward Dickinson, freight traffic manager J. A. Munroe, and general passenger agent E. L. Lomax. But he also included his two oldest daughters, Mary and Cornelia, and old friend Dr. E. L. Trudeau. The frail, sickly Trudeau had already founded his famous sanitarium at Saranac Lake for which Harriman had served as a trustee since 1891. Since their early days together at Paul Smith’s, Harriman’seldom missed a chance to invite the doctor on an outing.4

Everyone gathered at the Union Depot in Kansas City, where the train had been readied. Harriman and the girls were in high spirits, the rail officers quiet and deferential. They could not help but feel apprehensive over being locked in close quarters for more than three weeks with the man who held their destiny in his hands. At the same time, they were curious about him and eager to take his measure. Harriman was still a mystery to the men in the West, who knew him vaguely as a financier connected with the Illinois Central. What, if anything, did he know about railroads?

At two o’clock on the afternoon of June 17, 1898, the train chugged slowly out of Kansas City, “backing up” as railroad men said when the engine pushed from the rear, and rolled onto the Kansas division of the Union Pacific. The pace was leisurely, allowing Harriman to scrutinize everything in sight. The first night was spent at Wamego and the second at Ellis, where the visitors were treated to an outdoor band concert. By late afternoon on the third day, as the train ran toward Denver, the endless prairie dissolved into vistas of distant green forests and mountain peaks.

The train rolled past Denver through a lush valley wedged against a mountain wall until it reached Colorado Springs that night. There Harriman paused for two days to take the girls sight-seeing. He liked to visit every local attraction as if he had all the time in the world and nothing else to do with it. They went to Manitou, gaped in awe at the Garden of the Gods, then made the drive up Pikes Peak. The next day they ran through Clear Creek Canyon, where the roaring water had carved the rocky cliffs into dozens of grotesque shapes that lined the track. In the sixty-mile crevice with sides rising five hundred to fifteen hundred feet, the sky loomed like a narrow strip of cobalt above the jagged rock.

On June 22 the train returned to Denver and hurried to Cheyenne, where it picked up the Union Pacific main line. On the rolling prairie the girls saw herds of antelope and caught distant glimpses of coyotes. They paused for the night at Laramie, huddled between the Laramie and Medicine Bow ranges, then pushed on to Rock River in the middle of stock-raising country, the coal-mining town of Hanna, the continental divide at Creston, and the formidable Red Desert, once a favorite Indian hunting ground but now prowled mostly by sheep. Beyond the twisted sandstone cliffs called Point of Rocks lay Rock Springs, another Union Pacific coal town where the infamous massacre of Chinese miners occurred in 1885. That night they stopped at Green River, opposite some imposing bluffs that had eroded into all forms of weird figures.

Green River was the gateway to the Uinta Mountains and Utah, which had finally been admitted to the Union two years earlier. At Echo City Harriman learned that a small branch line had been ravaged by fire the day before. He hunted up the mayor and walked the town with him until satisfied that his help was not needed. On they went to Ogden, where the Union Pacific connected with the Central Pacific, and down to Salt Lake City, where Harriman and the girls roamed eagerly around the tabernacle and other attractions of Temple Square. The night was spent at Saltair, a new resort with a huge concert and dancing pavilion on the shore of the lake. Next morning they enjoyed a dip in the clear salt water.

They were the perfect tourists, willing to go anywhere to see anything, yet the rail officials found it hard to relax because they were being introduced to the Harriman’style. His energy and insatiable curiosity overwhelmed them. As J. B. Berry noted tactfully, “He was keenly alive to all the surroundings.” Harriman’seized on details others missed and fired questions nonstop until even veteran rail officials had to rack their brains on matters that had never occurred to them. Nor could they duck the line of fire, for Harriman had a way of pressing until he got an answer that satisfied him.5

At every stop the local superintendent and other officers climbed aboard and got the same intense grilling. Harriman’s sharp eye and tough, persistent questions jolted them. He could not be fooled because he seemed to know so much already, and smart officers saw quickly that it was dangerous to trifle with him. While riddling others with questions, Harriman’said little in return, leaving them to stew in uncertainty. No one could follow his thinking or divine its direction.

North of Ogden lay the Oregon Short Line and the Oregon Railway & Navigation road over which the Union Pacific reached Portland. The company had lost control of both lines, and Harriman was already deep into negotiations to reacquire them. This remote corner of the West had long tantalized entrepreneurs with its vast potential for wealth, and Harriman wanted to see it for himself. His train headed over the Short Line, then turned north at Pocatello to visit the huge mining complexes at Butte and Anaconda.

At Butte Harriman met Marcus Daly, the mining baron of whom one Montana paper grumbled, “If Christ came to Anaconda he would be compelled to eat, sleep, drink and pray with Mr. Marcus Daly.” Harriman was happy to share those activities with the genial Daly and quickly fell to arguing over who owned the best trotter. Before parting they agreed to settle the debate with a race for $10,000. When the race was held, Daly won and collected the bet. Harriman later insisted on a rematch, however, and this time his horse won.6

While Harriman poked around the mines, the girls ventured down the Anaconda chute and took snapshots of Indians. Later they all rode bicycles around the camp and then horses through the countryside. Harriman also got in some trout fishing on the ride back to Boise, where everyone plunged eagerly into the giant indoor natatorium for a swim. From Boise the train moved on to Umatilla, where it picked up the breathtaking Columbia River line into Portland. The stately peaks of Mount Rainier, St. Helens, and Adams on one side and Mount Hood on the other fired their imaginations, as did the Multnomah Falls and the fish-wheels along the river.

All this was frontier for Harriman. The vast spectacle of the country unfolding before him filled his mind with bold, immense ideas. Every new experience seemed to open his eyes to how much more could be done and to ignite within him the desire to do it. Even before he had conquered a kingdom there burned within him grand visions of empire. There was so much more to the West than he had ever dreamed, and once impressed with its majesty he never forgot the lesson.

The line terminated at Portland, but Harriman wanted to see more. After pausing only a few hours to explore Portland, the train rattled southward on Southern Pacific track toward Ashland, where the travelers spent the night of June 30. The next day they visited Mount Shasta, which offered views the girls found “exquisitely beautiful, and can not be excelled on the American continent.” They gasped in delight at the Rogue River Valley, Strawberry Valley, and the Sacramento River curling about the mountain’s base.7

After reluctantly leaving Shasta, the Harrimans spent the night at Delta, California. Shortly after their departure the next morning, the train was derailed, injuring the fireman and causing a delay of ten hours. While the crew waited for a wrecking train to rerail the cars, an unruffled Harriman hunted up a pole and went off fishing for a couple of hours. Next day they chugged into Monterey, where more magnificent scenery awaited them. Groves of oak, pine, and cedar trees draped the distant mountains and flanked the bay along the peninsula, where they enjoyed a long drive. That night Horace Burt hosted a dinner at the palatial Hotel Del Monte.

On Monday, July 4, the Harrimans arrived in San Francisco and were enchanted by it. Reluctantly they pushed on to Burlingame, where the next day they were guests at a luncheon hosted by Julius Kruttschnitt of the Southern Pacific. This was Harriman’s introduction to the man who later became indispensable to him. The stolid, burly Kruttschnitt, a walking encyclopedia of knowledge on railroads and the West, obliged Harriman with a steady stream of information. After lunch the Harrimans returned to play tourist for two more days in San Francisco before starting the long trip home.

On this homeward journey Harriman traveled the entire original transcontinental route for the first time. For three days his tireless eyes scanned the track and the country. He marveled at the ascent through the rugged Sierras and long, desolate stretches across the Humboldt desert to Ogden, where they switched from the Central Pacific to the Union Pacific. Through Weber’s Canyon, past the glowering Uinta Mountains and the sullen Red Desert, the Wyoming prairie and the Black Hills, the scenery mattered less to Harriman than the terrain. While the girls recorded its beauty, he calculated the cost of transforming it into a road comparable to the Illinois Central. He crossed the heart-stopping Dale Creek bridge and felt the engine struggle up Sherman’s Hill, the highest point on the road and the biggest obstacle to efficient operation.

Once into the flatlands of Nebraska, he studied the curvature and weight of the track, the bridges, depots, and outbuildings, looked over the repair shops at Grand Island, and took note of the lush crops filling the broad Platte River valley. On the afternoon of July 9 the train rolled into Omaha, having covered 6,236 miles in twenty-three days. They proved to be the most important miles Harriman ever traveled. His mind had gone much farther, leaping to possibilities he had scarcely imagined before the trip.

Harriman had headed west relishing the challenge of bringing a moribund railroad to life but knowing little of what the work entailed. He had examined the road, estimated what was needed to modernize it, and taken the measure of the men who ran it. Aware that they barely knew who he was, let alone what he could do, he had blown in like a whirlwind and stamped on them the indelible imprint of his authority before rushing out as abruptly as he had come. He had also surveyed the country, talked to shippers as well as bankers and businessmen, gauged the mood of the farmers on what their crops and livestock promised. In little over three weeks he had learned the West and come home a convert to its potential. The West became a shrine at which Harriman never ceased to worship. The reconstruction of the Union Pacific remained his major goal, but it also became the first step in a much larger vision of empire. The design had not yet unfolded to him, but the inspiration was there.

On the last evening of the trip, while everyone was enjoying dinner in his private car, Harriman announced, “I have today wired New York for 5000 shares of Union Pacific preferred at 66, and any one of you are welcome to take as few or as many shares as you like.” This was a revelation to the railroad officers, to see a financier actually put his own money into an enterprise before it had even shown what it could do. Those impressed enough to take Harriman up on the offer were not disappointed at the results.8

Harriman did more than invest his own money in the company. He also telegraphed New York for authority to spend $25 million at once for new equipment and improvements. The signs of prosperity he saw everywhere along the route convinced him that the road was about to receive more business than it could possibly handle. Labor and materials could still be had at depression prices; the time to act was now, before a revived economy drove them upward. So determined was Harriman to steal a march that he let some contracts for work on his own responsibility even though he knew the board would balk at a request of such magnitude.9

Harriman’s telegram fell like a bombshell on the board. The railroad was barely six months out of receivership and struggling to earn a dividend on its preferred stock. To entertain such a huge expenditure seemed the height of madness; it was, cried one director, an extravagance that would hurl the Union Pacific back into bankruptcy. The request was tabled until Harriman could argue his case in person. On July 14 he took on the executive committee in a long and heated session. The other members hammered away at Harriman with their misgivings but could not shake his confidence; in the end, with much shaking of heads and uttering of dire prophecies, they approved the request.10

Harriman had no illusions as to what some of the board members thought of him or, as Otto Kahn put it, “the fatal consequences to his career in case his forecast should turn out to have been mistaken or even premature.” He had also been buying Union Pacific common stock for months at prices ranging up to 25 even though no one believed it would pay a dividend for years to come. “You see,” sneered one financier to Kahn, “the man is essentially a speculator…. He will come to grief yet.” When Kahn mentioned this to Harriman, the little man retorted, “Union Pacific common is intrinsically worth as much as St. Paul. With good management it will get there.”

St. Paul was then selling around par. Kahn merely nodded and walked away. It sounded to him, he later admitted, like “the wildest kind of wild talk.”11

Schiff had walked the floor of his hotel in anguish the night he had purchased the Union Pacific, but Harriman’seemed unfazed by the enormous gamble he was taking. There was a toughness and certainty of purpose about him that unnerved even hardened financiers, but no one doubted that in this case the once conservative banker was putting his own future on the line as well as that of the Union Pacific.

In going for broke Harriman had one advantage that was in many eyes a liability. The railroad industry was the nation’s first big business, and by 1890 it had already grown hidebound in many respects. Railroad men dwelled in a world of eternal verities shaped by one immutable belief: experience was the best if not only teacher. To them Harriman lacked the hands-on experience necessary to run a large railroad. He had no “practical” background in how things were done.

It never occurred to most railroad men that this lack of experience was an asset in a rapidly changing world where yesterday’s habits became today’s obstacle. Harriman’s lack of experience in the nuts and bolts of operations meant that he had little to unlearn before he could begin to learn. With a mind free of the shibboleths that blinded so many rail officers, he could look at things as they were instead of how someone told him they were supposed to be.

And he was a fast learner. The speed with which his mind assimilated, sorted, and collated data seemed inhuman to those around him, as did his ability to pick something up much later at exactly the point where he had left it. Asked to explain how he managed it, Harriman thought for a while and then said, “I think that the mind is like these—what d’ye call ’em on this desk?—these pigeon holes. A man comes to me. I listen and decide on what to do; and then—it goes into a pigeon-hole.”

“And it’s always there?” asked the interviewer. “No trouble in finding it again at any time?”

“It’s always there.” Harriman pondered the matter, as if curious to know the answer himself. “It’s always there,” he repeated at last. “Whenever I need it again I find it there.”

“And you don’t know how you do it?”

“I don’t know how I do it.”12

The Harriman brain became a source of fascination among those close to him. What awed them was his ability to be so quick and incisive and still reach sound conclusions. Judge Robert S. Lovett, who later became one of Harriman’s closest friends and associates, marveled at this gift: “His mental processes were unlike any that I have ever seen. He never arrived at conclusions by reason, or argument, or any deliberative process that I could observe. His judgments seemed to be formed intuitively. The proposition was presented to him and he saw it. It was much like turning a flashlight on a subject. If interested, he saw it, and did not care and probably did not know how it was revealed. And his vision and measure of it was almost unfailingly clear and correct.”13

James Stillman, who overcame his early doubts to become one of Harriman’s closest friends and admirers, agreed that the little man’s brain was “a thing to marvel at. And yet it was that kind of brain which, if you could take it apart as you would a clock, and put it on a shelf to look at, would be distinguished by the incredible simplicity of its mechanism, and its ability to make the most complex problems solvable and common unto itself.”14

This ability to flash from insight to conclusion with lightning speed led to his being dubbed the “Human Business Machine.” But Harriman was much more than a calculator. He prided himself on his imagination and liked to say that lack of it was a serious defect in any man. Unlike most men, he never let experience glaze his vision. For Harriman the conventional wisdom was a point of departure, not a refuge.15

Few outsiders understood how Harriman’s mind worked. As a result, he has long been portrayed as a man who mastered the intricacies of railroading by immersing himself in detail. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Details were for him merely springboards to understanding how things should be done, and his gift for finding larger truths in the smallest incident was uncanny. From these insights flowed a grasp of the principles on which a railroad should be run.

During his first trip over the Union Pacific, Harriman happened to notice at one stop that it took a long time for the engines to take on water. His eye wandered up to the narrow pipe feeding the boiler. Why, he asked, were the discharge pipes only four to six inches in diameter? Because, came the railroader’s stock answer, they had always been that way, for reasons nobody knew. Harriman ordered new pipes with twelve-inch diameters installed, and crews were astonished to find that water stops took much less time.16

In upgrading the Union Pacific, what mattered most to Harriman was how well he trusted the officer in charge. He realized that it was crucial to have the right men in key positions if he was to accomplish great changes. In business as in war the general was always at the mercy of his staff. Harriman was slow to place his trust in a man, but once given he relied heavily on the man’s judgment. “Unless he could trust a man implicitly,” said Julius Kruttschnitt, “he would soon replace him with a man he could trust.”17

One of those key men arrived in June 1898, just before Harriman departed on his inspection trip. Judge William D. Cornish had served the Union Pacific as master in chancery for the long receivership ordeal before being tapped as the new first vice-president. A shrewd, patient negotiator, the tactful Cornish proved to be the perfect balance wheel for Harriman’s curt, abrasive manner. His sound judgment and skillful handling of subordinates enabled Harriman to concentrate on larger matters.18

Harriman’s business style demolishes the myth of him as a prisoner of detail. He told subordinates what he wanted, sought their advice, scrutinized their reports, decided what to do, and left the execution to them. Far from demanding piles of data, he insisted that even complex reports be pared down to a page or two. “While Mr. Harriman thoroughly understood the details of railroad work,” noted Kruttschnitt, “his policy was to select men who were competent to supervise and control the details, and then to give himself no further trouble about them.”19

If the officers did their job well, Harriman let them do it their own way. “He always said to the railroad people,” emphasized J. B. Berry, “that he looked to them for results and that he did not expect to instruct them in it.” Samuel M. Felton worked for ten years in important positions for Harriman yet saw him only once every month or two. “He analyzed men,” declared another officer, “much as he analyzed facts.” Sometimes he picked the wrong man, but incompetents did not last long under his system. Harriman was slow to praise and quick to criticize. He expected high-quality work and insisted that officers work together. Cost overruns never bothered him if he got the results he wanted.20

Nobody found it easy working for Harriman. “I say work for,” stressed Felton, “because no one worked with him. He was always the sole director, and sometimes imperious and arbitrary.” The most energetic officer scrambled to keep up with him; one auditor grumbled that Harriman would wear out any man in ten years. This edge of desperation was made worse by Harriman’s unfathomable way of leapfrogging from one topic to another without any obvious connection. He seemed to carry the office in his head—in those invisible pigeonholes that even he couldn’t explain.21

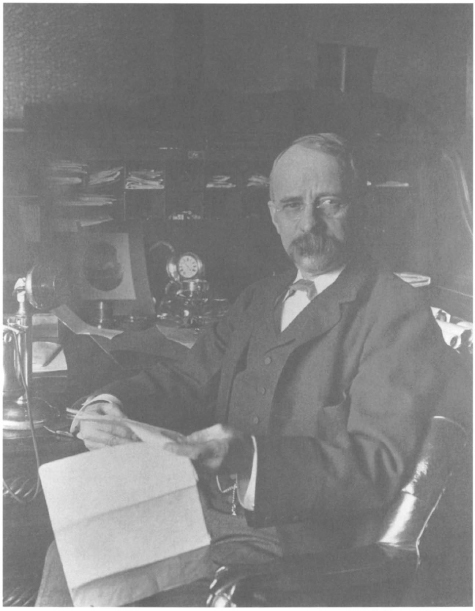

Man at work: E. H. Harriman at his desk, the omnipresent telephone at his elbow. (Union Pacific Museum Collection)

His mind flashed across a subject so quickly that no one could follow it. Once Harriman rattled off to Felton a string of figures nonstop for ten minutes, then tossed out another number as the conclusion to be drawn from the others. “Isn’t that so?” he demanded. “Wait a moment, Mr. Harriman,” pleaded the dazed Felton. “If I could understand all that as quickly as you do, then I should be sitting where you are.” Harriman laughed at that and repeated the figures more slowly.22

As Fish discovered early, Harriman wore out the telephone in his zeal to save time and transact business when he could not be present—a handy tool for one who fell ill often. When the telephone was not available, he used the telegraph, firing off messages in the same staccato style. Instead of scanning telegrams himself, he had the secretary read them to him and usually had an answer framed before the reading was finished. He grew to dislike writing letters as much as reading them and gradually reduced his output to a minimum as the telephone allowed him to do business faster.23

One reason Harriman avoided letters was the toll it took on both the stenographer scrambling to keep up with him and his own concentration. In his haste to spew out a message, he often produced wildly convoluted sentences like this one to Horace Burt, which outlines his relationship to the Union Pacific president:

Your telegram of the 4th regarding answer to Mr. Stubbs letter of the 3rd to me received here this morning, and I have answered Mr. Stubbs as per copy enclosed. The substance of his letter was communicated to me over the telephone on Saturday, at which time I directed Mr. Millar to wire you requesting that you advise me by wire what attitude I should take and answer make to Mr. Stubbs, but his message seems to have been put so that it indicated that I intended to take the matter up here, which I certainly do not unless it should be necessary in order to help settle the matter and save you so long a journey as coming here for this purpose and I desire you to understand that that is the attitude which I want you to consider me in towards this company and yourself,—that is, where I can take up a matter which would tend to help the Company & its officers I will be glad always to do it.

The sentence reads like a road map of Harriman’s mind at work: everything hangs together perfectly if you can follow its breathless twists and turns. But few of his officers could. Railroad men were methodical by nature and incapable of following the leaps Harriman’s mind took.24

Although this gap in intellect made subordinates uneasy in Harriman’s presence, it led them to believe in his genius. But something more attracted them even as he worked them to exhaustion: a magnetism born of his towering confidence in his plans. “He would not only convert you but would keep you converted,” insisted Felton. “The better you knew him, the more confidence you had in him. He had unbounded confidence in himself, and probably this confidence was so overwhelming that few could resist it.”25

Otto Kahn got a taste of this confidence early. Harriman came to Kuhn, Loeb one hot summer day in 1897 to persuade the bankers to take an interest in a certain deal. When Kahn showed no interest, a pale, haggard Harriman argued in vain to change his mind. Finally, he got up and stumbled to the door, then turned around and rasped, “I am dead tired this afternoon, and no good any more. I have been on this job uninterruptedly all day, taking no time even for luncheon. I’ll tackle you again to-morrow, when I am fresh. I’m bound to convince you, and to get you to come along.” To Kahn’s surprise, Harriman appeared the next day and pleaded his case until Kahn yielded as much to his persistence as his arguments. “His power of will was nothing short of phenomenal,” marveled Kahn. “I have seen him perform veritable miracles in the way of making people do as he wanted.” This was Kahn’s first lesson about Harriman; the second was that the deal turned out to be very profitable.26