16 Seeking Hegemony

Harriman is not only a railroad man but a financier. Above all, he is a strategist.

In the latter respect Morgan is said to be his inferior by capable judges. And he is ambitious; ambitious to surpass Morgan in the railroad world and perhaps if the real truth were known jealous of Morgan’s great supremacy…. Harriman has never let slip an opportunity to benefit the great systems he controls in the West, and has always been on the alert to prevent any rival from breaking into his field.

—New York World, May 12, 1901

The spectacular fight over the Northern Pacific earned Harriman another honor: his first extended profile in a New York daily. His name had drifted through the press with mounting frequency since 1899, but this was the first time a reporter bestowed on him the kind of personal portrait reserved for big newsmakers. The illustration accompanying the profile was an example of the bad generic art used by newspapers before the use of photographs became common. Its well-stuffed body looked more like Morgan than Harriman, and the fleshy face with its neatly trimmed mustache bore a mild resemblance to William Howard Taft.1

If the artist missed the real Harriman, perhaps had never even seen him, the reporter captured his elusive subject well. His vivid account was echoed by later writers until it became the stuff of legend. The reporter admired Harriman for having the courage to challenge Morgan. Thousands of men might relish seeing Jupiter challenged, but not one in a thousand dared to lead the charge himself. Harriman was a battler with ability, supreme confidence, and a quick mind. And as the Northern Pacific fight demonstrated, he possessed the one quality reporters loved most: he made good copy.

Harriman’s appearance left little impression except for an odd black derby that looked a size too large. He wore it two distinct ways: pulled forward, where the brim shielded his eyes, or jammed back on his head so that his ears stuck out. On the street he was as inconspicuous as the man with whom the reporter was the first to draw a comparison: Jay Gould. Both were small, slight, dark-skinned men with dark hair and eyes that glittered with hypnotic intensity. The reporter had heard men say that Harrimans eyes “could look through the steel side of a battleship.”

During the next few years the black hair grew thin and gray, and the dark eyes glazed with fatigue, but the driving energy remained. “He goes about his work as if he were on springs,” marveled the reporter. “He is chockful of nervous energy and bounds about from one place to another with never-ceasing restlessness. How he manages to buckle down to one thing long enough to complete it is a mystery to those who do not know him.” That he got an enormous amount of work done was owing in part to his friendship with James Stillman. The reporter believed he understood the nexus of ambition that bound Harriman and Stillman together. Harriman longed to become the dominant railroad man in the nation, Stillman the supreme banker. The obstacle in both their paths was Morgan.

The portrait that emerged was that of a remarkable man who had amassed great power and craved still more yet was anything but a lone wolf. His position owed much to the resources behind him: Schiff, Stillman, the Rockefellers. The real mystery was the relationship among these titans. Were they associates or rivals? Who led and who followed? How tight was the bond among them? With so little information available, it was easy to regard Harriman as a puppet dangled by the big money behind him until the sheer force of his presence and the scale of his actions revealed the puppet to have a life very much its own.

Although Northern Securities became a landmark in the history of American business, it was a less original use of the holding company vehicle than Harriman had already conceived. The idea behind a holding company was to control several roads with a minimum of capital, but Harriman and his banker friends had something more in mind: to impose order on the chaotic rail industry. Large profits required a steady flow of capital from Europe, but the bankers could sell American securities to their overseas clients only if the emerging rail systems were efficient, well-managed, and free from the strife that had bled them to death earlier. Achieving this stability was the goal of community of interest, the voting trusts, the advisory board, and every other device of the era.

In puzzling through the maze of railroads west of the Mississippi River, Harriman came early to the holding company. Several of his Illinois Central cronies had formed one in February 1896 but left it dormant for two years. Harriman joined with Stillman and Fish to revive it as a vehicle for locking up $13.6 million worth of Illinois Central stock. It took Harriman until December 1900 to activate the Railroad Securities Company. By then he and his friends had created a holding company for the Alton as well, but the Northern Securities suit had a chilling effect on any further use of holding companies until the courts resolved their legality.2

Railroad Securities slipped quietly back into limbo while Harriman groped for other ways to expand and integrate his empire. The community of interest began to crack at the seams as it became clear that there were too many interests with too little sense of community among them. It was hard enough to keep track of events, let alone keep faith, during the frantic months of 1901 when everybody seemed to be buying a piece of somebody else. Until the courts resolved Northern Securities, Harriman had no choice but to improvise.

The Southwest theater was becoming as volatile as the Northwest. Since emerging from receivership in 1895, the Atchison had shown surprising strength under its capable new president, E. R Ripley. Nevertheless, Schiff was convinced the “Atchisons independence cannot last very long,” and he did not want it in unfriendly hands. In the spring of 1900 he and Harriman had started buying Atchison stock, but Schiff’s efforts to enlist key foreign investors were blocked by Victor Morawetz, the financial maven of the Atchison.3

Schiff let the matter rest until a month after the Northern Pacific panic, then began picking up more Atchison stock. Hill urged him to make an offer directly to Morawetz, no doubt hoping to get Harriman looking southwest instead of northwest. After sounding his financial friends in Europe, however, Schiff concluded that Hills approach could not be more wrong. “Morawetz is very jealous of his position,” Schiff confided to Harriman, “8c the least intimation to him that you & we want to get in will induce him to do everything he can to keep us out.” The best course was to wait for Atchison stocks to slip from their present high prices. Then, Schiff urged, “we must have the courage to buy largely”—at least $40 or $50 million worth. The foreign investors would “go with us whenever we control enough stock to give us a chance in a contest, but we cannot count upon their help simply for loves sake, & it would be dangerous to even mention … what is in our mind.”4

This advice offers a rare insight into Schiff’s role in the partnership. To other eyes he was a quiet, dignified diplomat whose role consisted mainly of restraining the irrepressible Harriman. Yet part of the mortar binding them together was Schiff’s ability to conceive bold plans and undertake great risks. They had already bought the Southern Pacific and were still carrying their huge load of Northern Pacific when Schiff wrote this meditation on yet another major investment. Stillman too possessed this improbable blend of caution, driving ambition, and daring. Harrimans partners were not just powerful and well connected; they also complemented him well.

Schiff differed from Harriman in knowing when to draw the line, and he drew it emphatically at the Rock Island. During the hectic spring of 1901, the men who dominated that road offered it to Harriman. He liked the property and the price, but when he took the proposal to Schiff, he received a polite lecture on the limits of human endurance. How could any one man, even a genius, Schiff asked tactfully, run the combined Union Pacific-Southern Pacific systems and take on additional burdens? Even if the Rock Island could be legally acquired, there was a limit to the economic advantages of scale. Make the combination too gigantic for one man, however able, to oversee properly and it would cease to be efficient.5

Harriman listened intently to this argument. “You are right,” he conceded at last, “we had better leave it alone.”

Nothing was more difficult for Harriman than leaving things alone. The Rock Island temptation took care of itself that summer when it passed into the hands of four promoters who soon became known on Wall Street as the “Rock Island crowd.” But there were other properties lying around loose and plenty of raiders looking to piece together new systems or the facade of one to induce a buyout. A few brave souls were even building new lines. The toughest of them was Senator William A. Clark, who was pushing ahead on his proposed road from Los Angeles to Salt Lake. This was one challenge Harriman could not leave alone.

The Nevada desert seemed an unlikely battleground for the clash of titans. Visionaries had long dreamed of a direct line from Salt Lake City to southern California, where the burgeoning fruit business had begun to generate a large amount of traffic. But Los Angeles and San Diego were still small, sleepy towns, Las Vegas did not exist, and the mining industry in southern Nevada had faded with the decline of the legendary Comstock lode. The Union Pacific owned a line reaching as far south as Frisco, 277 miles from Ogden. In 1890 the Oregon Short Line had chartered a company to build from Milford, Utah, to Pioche, Nevada, but abandoned the project when money grew tight.6

The detritus of this project, consisting of some roadbed and tunnels, lay forgotten beneath the blazing desert sun and constant wash of shifting sands until 1898, when a new company called the Utah & Pacific built seventy-five miles of track from Milford to Uvada at the Nevada border. The Short Line gave this company its abandoned line in exchange for an option to buy the Utah & Pacific’s stock within five years. It also created a new company to extend the line from Uvada through Nevada but did no work on the project.7

Harriman ventured into this remote arena earlier than most people realize. His first foray reveals how far ahead his thinking ran. In the winter of 1899, while organizing the Alaska expedition, he sent Samuel Felton to inspect the Los Angeles Terminal Railway and report on “its desirability as a terminus for a transcontinental line of railroad.” At the time, Harriman had not yet reacquired the Navigation line and Huntington was very much alive; Harriman was looking at every possible avenue to the Pacific coast.8

The Terminal consisted of a twenty-eight-mile road from Los Angeles to the ocean at East San Pedro and three branches totaling another twenty-three miles of track. None of the lines did much business; it was a property waiting for a future that might never arrive. San Pedro, twenty-two miles south of Los Angeles, had a fine natural harbor. The federal government had plans to improve it and construct an inner harbor at Wilmington, where the Terminal company owned a large amount of salt marsh and tide land. No one considered this land of any value, and no one in the energy-starved Southwest dreamed that beneath it lay a vast reservoir of oil that would enrich the Union Pacific Railroad half a century later.9

Harriman was seeking an outlet to the sea for the flow of traffic along his Utah lines. The problem was that the route contained little local business to help support a new line. Moreover, Huntington had fought a masterful delaying action against the improvements at San Pedro to protect the port he was developing at Santa Monica. Any entrance into southern California would have to contend with Huntington’s viselike grip on the region, and Harriman already had problems enough with Huntington at the Ogden gateway.10

The Terminal lines belonged to a promoter named R. C. Kerens, who had tried for nearly a decade to interest the Union Pacific in the project. In the spring of 1899 he found an unexpected supporter for the line. Kerens promptly sent an emissary to W. H. Bancroft, seeking this time not to enlist the Union Pacific as a partner but to buy or lease its line south of Salt Lake City. Bancroft got the message quickly. “I infer from his conversation,” he telegraphed Harriman, “that W. A. Clark of Montana is behind him.”11

This was a threat Harriman dared not ignore. The whole thrust of Clark’s career had confirmed J. B. Bury’s adage, “There is no force in nature more terrible than a young Scotsman on the make.” Born in 1839 to Pennsylvania dirt farmers, Clark went early to Iowa and then Montana, where he endured incredible hardships to prosper as a merchant amid the brutal free-for-all of the gold camps. Gradually his interests spread to banking; then, in 1872, he made a daring leap into mining at a small, drowsy camp named Butte, where he erected the first smelter and acquired the lucrative Elm Orlu mine. In 1884 Clark happened on some ore samples from a remote mine in Arizona called the United Verde. Recognizing their value, he bought the mine and turned it into an enterprise that at its height fetched him profits of $10 million a year.12

By 1890 Clark had put together an empire of mines, mills, smelters, banks, stores, utilities, newspapers, and lumber holdings that made him one of the most powerful men in the West. A small, trim man standing five feet seven and weighing 140 pounds, Clark looked as forgettable as Harriman. Clear, cold blue eyes illuminated an otherwise drab face masked by a beard. His personality was a vacuum of austerity concealing a shrewd, calculating intelligence. “His heart is frozen and his instincts are those of the fox,” said one of Clarks many detractors; “there is craft in his stereotyped smile and icicles in his handshake. He is about as magnetic as last year’s bird’s nest.”13

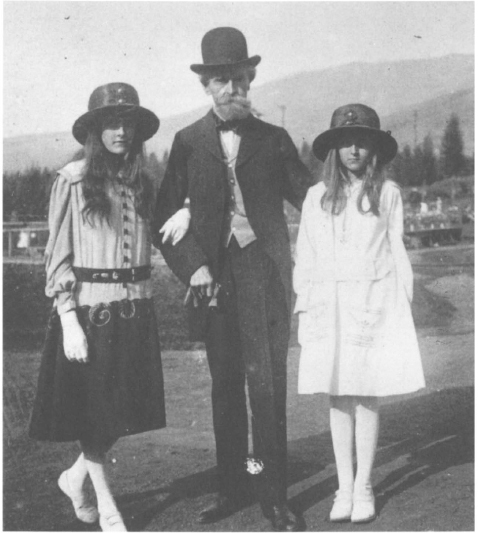

Formidable dandy: Mining millionaire turned social denizen W. A. Clark poses with his two daughters. (Montana Historical Society)

As Clark amassed wealth and success, however, the austere Scot turned into a dandy, a peacock addicted to things French, to attractive women, and above all to steady doses of public adulation. He took prolonged trips to Europe, began the obligatory art collection, and dabbled in cultural affairs. To hostile eyes he was vintage arriviste pure and simple, but nothing about him proved pure or simple. In 1900, when Clark was sixty-one, the whole bizarre range of his interests collided in a series of events that kept his name dancing through the headlines for weeks at a time.

Part of his new image involved a gargantuan mansion being constructed on Fifth Avenue and 77th Street, which sneering New Yorkers referred to as “Clark’s Folly.” Through the pages of the city’s dailies, they followed avidly the progress of this latest addition to Millionaires’ Row as well as the saga of the new wife Clark hoped to install there. Years earlier Clark had assisted the family of a miner killed in one of his mines. Two of the children were talented, attractive girls. Clark sent the eldest to France to study drawing. A widower since 1893, he soon fell in love with his protégé and proposed to her three years later. The idea infuriated his eldest daughter, Katherine, who was a year older than the stepmother she was about to inherit.14

Titillating as this soap opera was, it paled before the major scandal in Clark’s life. His hunger for public adulation propelled him into politics. He went after a seat in the United States Senate in the only way he knew: he bribed the legislature to give it to him. His brazen tactics were too much even for the Senate, which refused to seat him. In desperation Clark resigned and had the lieutenant governor reappoint him while the governor was absent, but that clumsy ruse fell flat. The Senate rejected him again, forcing Clark into a humiliating retreat from Washington.15

This episode earned Clark a different brand of public attention than he craved. “No election for a seat in the United States Senate has ever been so productive of scandal,” sniffed the New York Tribune. Mark Twain paid Clark his own special brand of homage. “By his example he has so excused and so sweetened corruption that in Montana it no longer has an offensive smell,” he wrote. “He is as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag; he is a shame to the American nation.”16

None of this swayed or slowed Clark, who had the gall of a gambler and the certitude of a pope. While the critics raged, he moved serenely along with his mansion, his marriage, and his campaign for reelection to the Senate in the fall of 1900. Nor did he neglect his business affairs. Apart from Kerens’s activities in Los Angeles, two developments called his attention to the Nevada desert that year. The discovery of a new bonanza mine, Tonopah, sent prospectors flocking into southwest Nevada and triggered a revival of the mining industry. Then Huntington died, removing the major obstacle to developing San Pedro as a port.

Clark saw that the proposed through line could tap the new mines in Nevada and open the mineral district of southwest Utah to development. Less than two weeks after Huntington’s death, he announced that he would back the new line. The news caught Harriman while he was chasing the Southern Pacific and the Burlington as well as rebuilding the Union Pacific. While Harriman was preoccupied, Clark stole a march. In 1890 the Short Line had graded forty miles of line from Uvada to Caliente along with a branch from Caliente to Pioche. It had also surveyed a line through Meadow Valley Wash canyon and filed maps but done no work. The Union Pacific assumed that all rights to this route had passed to the Utah & Pacific, but Clark discovered that in 1894 it had been exposed for taxes and sold to the county. He also learned that a company called the Utah & California had surveyed the same route in 1897.17

It quickly became apparent that any feasible route from Ogden to Los Angeles had to pass through Meadow Valley Wash, which extended 110 miles southwest from Caliente. In March 1901 Clark incorporated the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad, swept the Terminal properties into it, and announced that it would build the new road. He also acquired the defunct Utah & California and title to the original survey. His engineers commenced a new survey of Meadow Valley Wash, arguing that the Short Line route had been abandoned. When the federal land office upheld Clarks claim, he sent crews onto the entire Uvada- Caliente route.18

Caught by surprise, Harriman knew Clark well enough to waste no time on talk. He appealed the ruling, ordered the Short Line to exercise its option on the Utah & Pacific, and told Bancroft to rush construction on a new road from Ogden to Los Angeles. This was the kind of galvanizing order that railroad men loved. As Bancroft began pouring crews and material onto the disputed route, the outnumbered San Pedro crews tried to slow them by stringing barbed wire and filling cuts with rocks and timber. The mood grew tense but stopped short of violence.19

On April 24 the Department of Interior reversed the land office decision and awarded the old graded route to the Short Line. The struggle shifted to Meadow Valley Wash, where the prize would go to the first company that filed its map with the land office. Horace Burt rushed to the scene along with the engineer who had done the original survey in 1890. When the Short Line’s engineers arrived in the narrow canyon, the dailies had the kind of spectacle they loved: two teams of surveyors racing to find separate lines in a cramped space with barely enough room for one decent line. In June the legal battle resumed at Carson City, where battalions of lawyers descended on the sleepy courthouse for a pitched battle of their own.20

In an age innocent of television, the clash of business titans was a favorite spectator sport for newspaper readers, and the bombast blowing in from the desert was a treat to relish. The court upheld the injunction against the San Pedro but allowed its work in the canyon to continue. The Short Line engineers whipped through their survey of Meadow Valley Wash in only twelve days and filed their maps first despite San Pedro protests that the maps were nothing more than copies of the original survey. Grimly the San Pedro crews threw up barricades across one end of the canyon while they graded frantically at the other. The Short Line men smashed through the barrier, but little fighting occurred. Clark got the court to enjoin the Short Line from doing any work in the canyon, which forced both sides to the bargaining table.21

Both Harriman and Clark were ready to compromise. The desert could barely support one line; moreover, Clark had no way to get into Utah or Harriman into Los Angeles without spending a lot more money. The question was what kind of deal to cut. It had to satisfy two tough bargainers and also stand up to the mounting attack on rail mergers. While dickering over terms, Harriman came to the realization that the answer lay in Clarks colossal vanity. The year had been kinder to Clark than to Harriman. He had reclaimed his seat in the Senate and married his young sweetheart. These pleasant distractions took some of the edge off Clarks business ambitions. He was willing to share the desert line with Harriman; all he wanted was the glory of building it. This, Harriman discovered, was the key to the solution.

In September the lawyers drew up a memorandum providing for a joint survey of Meadow Valley Wash and leaving all disputed points for Clark and Harriman to resolve personally. Publicly Clark encouraged every story that he was not only constructing the road but planning to link it with the Gould system. Privately, he assured Harriman of his intention to abide by the September memorandum until they could reach a broader agreement. Harriman understood the distinction between public posturing and private diplomacy. He did not mind the rumors, so long as they were not true; they might even deceive Gould.22

Harriman knew Clark was difficult to deal with and showed rare patience as the negotiations dragged out for months. On July 9 he was rewarded with a secret agreement in which Clark agreed to sell him a half interest in the San Pedro and the Empire Construction Company, which had been formed to build it. While this ensured Harriman ultimate control over the Los Angeles line, it also saddled him with Clark as a partner. The message was clear: Clark still wished to preserve the illusion that he was going it alone. As Harrimans chief adviser, W. D. Cornish, explained privately, “Mr. Clark is very sensitive on the point of his road being built as a San Pedro proposition. We are less tenacious about sentimental considerations but are looking to the final result.”23

There was a good reason why Clark’s vanity in demanding public recognition for building the road did not bother Harriman. The line was a crucial artery in his plan to dominate transcontinental traffic between Oregon and southern California and had to be kept out of rival hands. Having been burned by the furor over Northern Securities, Harriman’saw an advantage in keeping the real ownership of the San Pedro disguised for as long as possible. The most remarkable thing about this deception was how well it succeeded. Rumors of a deal between Harriman and Clark abounded, but nobody knew who got what. When the Short Line transferred all its track south of Salt Lake City to the San Pedro, Clark announced solemnly that it was “an absolute purchase, and Mr. Harriman retains absolutely no interest in the property.” Even skeptics were convinced that Harriman had not gained control.24

On a bright Sunday morning in May 1903, Harriman and Clark sat down in San Francisco with their chief lieutenants to thrash out a procedure for building the road. The session lasted all day and produced the terms Harriman wanted. A few days earlier Clark had rejected them, but at the Sunday meeting Harriman dressed the same terms in different clothes and the senator swallowed them whole. Clark would get the glory and Harriman would get the road.25

But it did not come easy. Harriman and Clark agreed to create a committee of four to build and operate the road, with any dispute to be resolved by the two leaders personally. Harriman never liked doing things by committee, and he sensed from the outset that there would be trouble. His instincts proved correct; instead of the six months boldly predicted, the construction took nearly two years. But the secret remained intact. Not until October 1904, when Harriman mentioned the purchase in the Union Pacific annual report, did the news leak out that he owned a half interest in the road.26

Japanese doubts about the American way of business surfaced much earlier than most people realize. During the winter of 1901, when both community of interest and the merger mania were on the verge of a frenzied outburst, the director general of Japans imperial railroads shook his head dubiously at the American example. “The amalgamation of roads does not strike me favorably,” he admitted. “The community of ownership is fraught with danger and will work detrimentally to the interests of the people.”27

A year later Harriman was coming to the same conclusion. As the Northern Securities fight graphically demonstrated, the community’s members had failed utterly to devise ways of resolving their conflicts. Gradually the harsh truth dawned on them that cooperation among roads had limits that could not be overcome. Harriman learned this when he tried vainly to accommodate the traffic needs of both the Alton and the Illinois Central. Fish pressed him for more business at Omaha and protested vigorously when the Milwaukee demanded and got improved facilities there.28

Disputes flared over the exchange of traffic at Ogden and Denver as well. When a clash erupted in the Columbia River valley, Harriman had to assure a suspicious Hill that “I have done nothing to antagonize the situation and will not.” Neither tact nor appeasement helped in most cases because concessions made in one direction annoyed some other interest, which promptly demanded new concessions in return. The community that appeared so united from without was a house divided within. The conflicts worsened steadily after 1901, eroding the enthusiasm and optimism that characterized the early faith in community of interest.

Harriman’s relationship with George Gould had grown increasingly strained since the Southern Pacific purchase. They still sat together on several boards, but their interests were diverging in ways that hampered efforts to promote harmony. So far Gould had done nothing with his newly acquired Rio Grande roads, but east of the Mississippi River he launched a bold plan to forge a line to the Atlantic seaboard. No one had ever created a true coast-to-coast system, although Huntington had come close. Even Harriman had remained immune to this ambition.

Three major pieces of the line were already in place for Gould. The parent Missouri Pacific road reached Pueblo from St. Louis and Kansas City. From the latter cities the Wabash extended Gould’s lines to Toledo and Detroit. In the fall of 1900 Gould had picked up the Wheeling & Lake Erie, which ran from Toledo to Wheeling, West Virginia. The key to Goulds grand scheme was reaching Pittsburgh, which generated an enormous traffic that was monopolized by the Pennsylvania Railroad. When one of Gould’s officers discovered a good route from the Wheeling road to Pittsburgh, Gould decided to challenge the most powerful railroad in America.29

Stung by Gould’s audacity, the Pennsylvania retaliated with every weapon in its arsenal—tying Gould up in court, in the state legislature, and on several other fronts. Unfazed, Gould sprang another coup in the spring of 1902 by acquiring the Western Maryland, which ran from Baltimore to Connellsville, Pennsylvania, only forty miles from Pittsburgh. To reach the seaboard, Gould had only to complete his new road to Pittsburgh and connect it to the Western Maryland.30

Gould’s eastern forays had a subtle but profound effect on Harriman. While Harriman was delighted to see Gould’s energies and resources squandered on a distant front, he could not ignore one danger signal. If Gould was endeavoring to forge a transcontinental line, he would need a line from Salt Lake City to the Pacific coast. Harriman had already shut him out of the Southern Pacific and the San Pedro (although Gould did not yet know about the latter). Would Gould dare to undertake construction of his own line?

One complex deal with Gould did little to reassure Harriman. During the fall of 1902 both men were drawn into the affairs of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company (CFI), which was vital to them as a prime source of traffic for their roads and as the major independent steel company in the West. Railroads depended on steel companies for rails, bridge materials, and other needs. In 1900 only six firms produced steel rails, and they fixed prices on their own terms. This collusion frustrated Harriman’s efforts to get better prices through large-scale buying. The formation of United States Steel in 1901 tightened this stranglehold by sweeping two of the largest firms together, and the traffic boon kept the mills humming with more orders than they could fill. In the bitter fight between the railroads and the rail makers, Harriman wanted to preserve CFI as an independent supplier.31

In the spring of 1901, however, the lynx eye of “Bet-a-Million” Gates fell on the property. Having just been elbowed out of the steel industry by Morgan, Gates viewed CFI as a promising reentry vehicle. But CFI president J. C. Osgood blocked Gates’s efforts at every turn. The fight headed toward a showdown during the summer of 1902 amid a crossfire of threats and injunctions. By this time Harriman must have grown weary of Gates’s portly shadow blighting his path. Whatever he thought of Gates personally, he regarded him as a rogue elephant lurching recklessly through companies in search of profits and indifferent to the debris left in his wake. Convinced that Gates only wanted CFI to unload on United States Steel at a blackmail price, he joined Gould and Edwin Hawley (whose Colorado & Southern also relied heavily on CFI traffic) in an already confused contest for control.32

Early in November Harriman invited Gould and Hawley to his office for a conference at which they agreed on a proposed board and composed a circular soliciting proxies. Their campaign succeeded in shoving Gates out of the picture. Then, inexplicably, Gould withdrew from the alliance and solicited proxies in his own name, claiming that Harriman and Hawley had used his name without his consent. “It is now taken for granted,” wrote one pundit, “that Mr. Gould intends to play an independent part in the various schemes of rival interests.”33

This was exactly what bothered Harriman. Did Goulds stand indicate that he was moving away from the community of interest to play a lone hand? The CFI fight was settled by a compromise giving each faction places on the board, but it was small change compared to what might follow if this breach was a prelude to larger ones. Then, in March 1903, a new line called the Western Pacific was chartered. Despite Goulds prompt denial, a Denver paper blared, “GOULD TO BUILD INDEPENDENT LINE TO PACIFIC COAST.”34

While Harriman watched the Western Pacific for evidence of Gould’s presence, he also had to deal with more immediate threats from the Atchison. In the summer of 1902 Atchison president E. P. Ripley decided to extend a small road called the Phoenix & Eastern from Phoenix to a connection with the Southern Pacific at Benson, Arizona. Ripley also wanted to push beyond San Francisco to the region between the ocean and the mountains, where a rich traffic in timber beckoned. But when he tried to buy a small road there that summer, Harriman’snatched it up first. Undaunted, Ripley grabbed a tiny line that hauled redwood timber as a base in northwest California for what could turn into a construction war with the Southern Pacific.35

Faced with threats on so many fronts, Harriman told Atchison chairman Victor Morawetz bluntly that he considered both the Phoenix and northern California lines an invasion of territory belonging to the Southern Pacific. That this stand was inconsistent with the one he had taken on territorial boundaries in the Northwest troubled him not at all. He saw in Arizona the possible evolution of a small local road into one paralleling the Southern Pacific; in California he feared the construction of a line all the way to Portland. This time Harrimans tough stand worked against him. The Atchison had neither the plans nor the money to undertake either project, but Harriman’s obvious concern gave Mora- wetz unexpected bargaining power. When Harriman demanded that the Atchison sell him the Phoenix and abandon the region south of that town, Morawetz replied that any deal had to include a settlement for northern California as well. Later Morawetz admitted that he got the idea for a parallel line from these negotiations; Harriman had simply overplayed his hand.36

With negotiations at an impasse, Harriman and Schiff reconsidered their earlier plan to buy Atchison stock. But they could not buy everything. Breathless rumors of new construction or mergers sprouted faster than they could be denied, and Wall Street was addicted to rumor. Some were serious and some silly, but Harriman dared not ignore them lest he miss the ones that mattered.

By the end of 1902 the highly touted community of interest was crumbling as one interest after another marched in its own direction despite the pleas and threats of Harriman and others. Although his empire had grown, hegemony remained an impossible dream. He had found no way either to harmonize, or Harrimanize, his rivals. The diplomacy of big business had come to the same dreary impasse as that among nations: no one wished to fight, but no one could find terms on which to make peace.

Even worse, an uneasy public mood was fast turning the bigness of business into a political minefield. Few major business figures had yet grasped the importance of stepping gingerly through its explosive controversies. The attack on Northern Securities had already served warning; another came in December 1902, when the ICC decided to hold an inquiry into the community of interest. The hearings produced few revelations; both Harriman and Hill danced their way around questions with the usual blend of vagueness, temporary amnesia, and outright lies. But the commissioners delivered one pertinent message to Harriman. They zeroed in on the collusion implied in the roles of Stubbs and Miller as traffic chiefs and on the new holding company for the Burlington. These turned out to be the most vulnerable salients, just as Hill had said they would be. Although little was revealed about them, the commissioners left no doubt that the last word had not been heard on the subjects.37

What, then, could be done? The sun of prosperity still shone brightly on the railroads as it did on the nation, but the industry still had not put itself in position to wring maximum returns from it despite the record profits many roads were piling up. A dozen years earlier two giants of the industry, Jay Gould and Collis Huntington, had tried to interest their peers in a bold plan. “When there is only one railroad company in the United States,” Huntington had growled to a reporter, “it will be better for everybody concerned, and the sooner this takes place the better.”38

The idea was far too visionary for other railroad men and was quickly dropped. Although the current craze for consolidation had alarmed the public into believing this was where the industry was heading, no one took such an idea seriously or talked in those terms—except possibly for one man who had a way of conceiving plans that others thought inconceivable. Not a word on the subject escaped his lips, but the full depth of Harrimans ambitions had yet to be plumbed. Was there ticking somewhere in the back of his indefatigable brain a variation on the theme of the One Big Railroad?39