17 Seeking the perfect Machine

E. H. Harriman is not a railroad builder. He is not a pioneer. He took the labor off the hands of other men, Crocker, Stanford, Huntington, bought in a lump the life-labor of these men, greater perhaps than himself, and reared upon their hard-built foundations a structure of his own planning—the Harriman System…. He followed the path blazed out by the great pioneers—followed it and built it over anew upon a plan and scale of marvelous perfection

An executive officer must be judged by the results of his acts. His methods are a question of the day. His results are for all time.

—Wall Street Journal, August 25, 1906

One clue to Harriman’s management style eluded all but a few observers sharp enough to look more at what than who his officers were. Nearly all the men who oversaw his roads had been trained as engineers: Horace Burt on the Union Pacific, Samuel Felton on the Alton, S. R. Knott of the Gulf line, and Julius Kruttschnitt of the Southern Pacific. Harriman wanted not merely top engineers to do the work but managers who understood what the engineers were telling them.

As the newest member of this team, Kruttschnitt had to undergo the usual Harriman rite of initiation. The man who would later be hailed as the “von Moltke of transportation” found himself walking a stretch of Southern Pacific roadbed with Harriman one day. Harrimans roving eye stopped on one of the bolts holding a rail in place.

“Why does so much of that bolt protrude beyond the nut?” he asked abruptly.

“It is the size which is generally used,” said Kruttschnitt.

Harriman’s eyes blazed. “Why should we use a bolt of such a length that a part of it is useless?”

“Well,” admitted Kruttschnitt, “when you come right down to it, there is no reason.”

They walked on in silence. Harriman’stopped suddenly and asked, “How many track bolts are there in a mile of track?” Kruttschnitt did a quick calculation and produced a figure. “Well,” retorted Harriman, “in the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific we have about eighteen thousand miles of track and there must be some fifty million track bolts in our system. If you can cut an ounce off from every bolt, you will save fifty million ounces of iron, and that is something worth while. Change your bolt standard.”1

The Southern Pacific held the distinction of being the largest transportation system in the world. Its 9,441 miles of rail and 16,186 miles of water lines covered routes from New York to New Orleans and from San Francisco to the Far East. The railroad earned more per mile than any other transcontinental line but also cost more to operate. No western road had a more richly diversified traffic or was in a better position to make money on its local business. But it also had a whopping $350 million funded debt and had never paid a dividend, which made it unappealing to investors.2

The smart money on Wall Street thought Harriman had paid too high a price for a sprawling system that required heavy expenditures. The smart money, however, did not understand what Harriman was doing. He was not merely trying to assure control over the entire route to the coast; he intended to rebuild the Southern Pacific and turn it into a cash cow just as he had done with the Union Pacific. In that task Kruttschnitt assumed the role Berry had played in reconstructing the Union Pacific.

In November 1901 Harriman’summoned Burt, Berry, Kruttschnitt, and William Hood, the Southern Pacific’s able chief engineer, to New York. He was ready to implement several projects Huntington had started but left on the drawing board because of their cost. Kruttschnitt brought along a load of blueprints, maps, and statistics for Harriman to examine, but visitors kept interrupting their sessions. Finally, Harriman invited Kruttschnitt to his house for dinner. Afterward, poring over the plans and blueprints, he peppered the engineer with questions, scarcely pausing to hear the answer before asking another about the advantages of this method over that one, the economies to be gained, the increase in capacity to be derived. “The swiftness with which he covered the ground was astonishing,” marveled Kruttschnitt.3

They finished in two hours, and Harriman told Kruttschnitt to be present at the executive committee meeting next morning. The plans called for spending $18 million. Harriman breezed into the meeting and explained the work, its costs and benefits, in concise terms almost before the other members had settled into their seats. Kruttschnitt was stunned to hear a unanimous vote of approval for everything. What kind of man, he wondered, could digest $18 million worth of work for a thousand miles of railroad in rugged country and spit it back so clearly that he got immediate approval? As he prepared to leave, Kruttschnitt asked Harriman cautiously how fast he should go in committing the funds.

“Spend it all in a week if you can,” replied Harriman.4

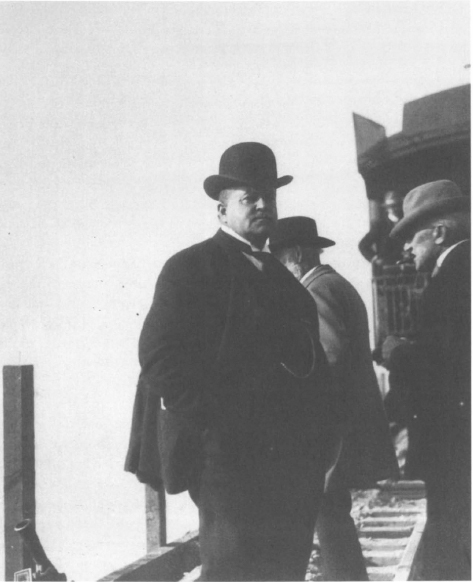

Walking encyclopedia: Julius Kruttschnitt, the man of many facts, who became Harriman’s chief operations officer. (Union Pacific Museum Collection)

Harriman proved to be as good as his word. Between 1893 and 1901 Huntington had spent about $12.4 million on improvements for the Southern Pacific. During the next eight years Harriman poured an astonishing $247 million into making it the equal of the Union Pacific. He followed the same master plan, shortening the Central Pacific fifty-one miles, cutting its maximum grades from 90 feet to 21.1 feet, reducing 16,625 degrees of curvature to 3,889 degrees, a savings of more than thirty-five complete circles. As a dinner speaker quipped, Harriman’straightened out a line long accused of being crooked.5

The Montalvo-Burbank cutoff was well under way at the time of Huntington’s death. Once Harriman completed it in 1904, he turned immediately to the Bay Shore cutoff, a radically improved entry into San Francisco. The original thirteen-mile line, a long, rugged detour to the west of the San Bruno Mountains blockading the southern approach to the city, had 796 degrees of curvature and a maximum grade of 158 feet. The growing city also bumped against the mountains, ruling out any possibility of improving the old line.6

This was precisely the challenge Harriman loved: a problem with no apparent solution except one so bold and costly as to defy the faint of heart. The answer was a direct route along the shore east of the mountains, shortening the line about 2.5 miles and drastically reducing grades and curvature. This required five tunnels, several bridges, and some heavy grading that brought the cost above $800,000 per mile. Completed in December 1907, the Bay Shore cutoff provided a double-track line into expanded terminal facilities at water level. A new bridge at Dumbarton Point enabled trains to cross the bay by rail instead of using ferries.7

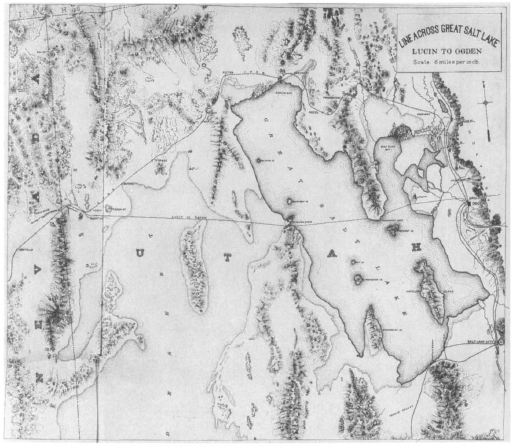

By far the worst bottleneck on the system was the section that wound its tortuous way through the Promontory Mountains north of Salt Lake. Since the 1870s engineers had pondered the obvious solution of running track straight across the lake. This would lop forty-four miles off the route, eliminate vast amounts of curvature and grade, save hours of transit time, and slash operating costs. The problem was the lake itself. Although soundings had been taken since the 1860s, no one really knew where the bottom was; legend claimed that parts of the lake were bottomless. Since salt water was heavy, the waves whipped up by storms pounded with frightening force, and the salt might corrode building materials. No one knew for sure whether the lake was rising or retreating. In recent years it had receded several feet. Was this part of a natural cycle, or would it continue because irrigation projects were tapping its feeders?8

Huntington had finally decided to tackle the monster late in 1899 after receiving a report from Hood, but he died just as construction was about to begin. Harriman found himself in a ticklish position. Hood urged him to continue the project; Berry disagreed because he did not trust the lakes changing water level. Amid all the arguments, one point shone through with blinding clarity to Harriman: the challenge of doing what others said couldn’t be done. This was no rash act of ego. Hood’s thorough report made a compelling argument for the feasibility of the project, and the advantages of crossing the lake were obvious.9

The new line ran from Ogden across Bear River Bay to the tip of Promontory Point, crossed the large western arm of the lake to a point called Lakeside, and intersected the main line just beyond Lucin, fifty-eight miles from the lake. It required seventy-eight miles of new track along with eleven miles of permanent and sixteen miles of temporary trestle. Enormous loads of lumber flowed in from the forests of the Northwest for piles, bents, stringers, caps, and buildings. A steamboat had to be built on the lake and twenty-five giant pile drivers in San Francisco.10

It looks simple on paper: A map of the Lucin cutoff line across the Great Salt Lake. The original Union Pacific-Central Pacific line can be seen skirting the northern edge of the lake. (Union Pacific Museum Collection)

To move a mountain of fill, Harriman purchased three hundred mammoth side-dump cars called “battleships,” which carried eighty-ton loads. Eight giant steam shovels gouged rock and gravel from nearby quarries, and eighty locomotives hauled an endless procession of cars to the lake. The company scrounged every spare car it could for the work. Everything had to be brought to the site across a road already jammed with traffic. Water for the men, the steam shovels, and the locomotives—half a million gallons daily—was imported in tank cars from as far away as a hundred miles.11

An army of workmen three thousand strong worked ten-hour shifts around the clock seven days a week. They earned decent pay and kept it. There was no place for them to go; the ban on liquor was so strict that incoming parcels were searched. A station house was put up every mile across the lake and a boardinghouse erected on a platform above the waves. The company supplied cooks and provisions and charged four dollars a week for board. To house men with families, it set up a camp of boxcars on sidings at Lakeside.12

But in practice: One of the countless trains of gravel cars dumps its load into the seemingly bottomless Salt Lake. (Union Pacific Museum Collection)

Harriman demanded both safety and sobriety on the site. Despite the difficult and hazardous work, no lives were lost and only one man suffered a serious injury. On the subject of drinking on duty Harriman was a fanatic who resorted to any means to stop it or ferret it out. When a story reached him about an engineer whose work suffered because he was often drunk, he put Bancroft on the case personally and did not relent until the charge had been completely discredited.13

Despite Hood’s careful preparations, the lake fought him at every turn. The first pile driven down for the temporary trestle at Bear River simply vanished. Another was placed atop it and also dropped out of sight at one blow. The engineers punched through fifty feet of soft mud before they hit a solid bottom. On the west side of the lake they found the opposite problem: a crust of nearly solid gypsum that yielded only an inch or two to the blow of a pile driver. Sometimes a pile went down easily for thirty feet only to spring back up when it struck the gypsum. In some places steam jets had to be used in place of the giant hammers.14

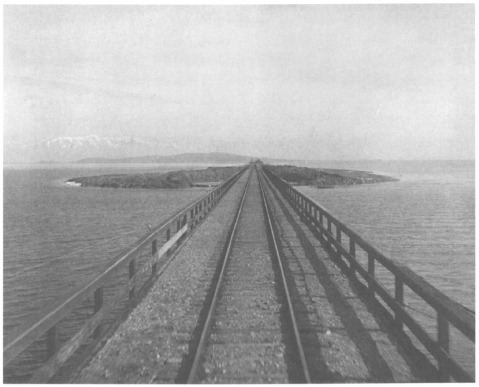

The straight and sinking road: A view of the Lucin cutoff line to the sink. (Union Pacific Museum Collection)

The engineers also learned to their dismay that ordinary fill simply floated away in the heavy salt water, forcing them to dump thousands of tons of rock into what seemed bottomless pits before they could use dirt and gravel. Hood had planned a twenty-foot-wide roadbed atop a permanent trestle fifteen feet above water no more than twenty-four feet deep. He assumed, therefore, that the largest embankment needed was about forty feet high. It turned out to be fifteen times that amount as ton after ton of fill simply vanished. Two places proved especially frustrating, one at Bear River and the other on the west arm of the lake at a station called Rambo.15

Hood completed the temporary track across the lake in March 1903, and the first locomotive puffed hopefully forward from Ogden. When it reached Bear River, the embankment suddenly sank out of sight, leaving the engine wallowing in two feet of water. Glumly the engineers realized that the real battle for the cutoff had begun. The problem was the lake’s peculiar crust, which tended to crack and sink under the weight of the fill. No one could predict where, when, or how much this would happen; it had to be learned by trial and error at every weak point. The track was raised and filled anew; a week later it sank beneath a work train, scaring the wits out of the crew. Again and again it sank, always to a point just above the fill. The faint of heart looked anew at the legend that the lake was a bottomless pit.

For twenty-one months the battle raged. Nearly twenty-five hundred men toiled at the task day and night. An endless procession of “battleships” rumbled forward to drop loads of rock and gravel into a maw that swallowed them only to sink yet again. The engineers watched every dump anxiously, their hopes rising only to be deflated by the next collapse. “We know what it ought to do,” cried one in frustration, “but what we don’t know is why it doesn’t do it.”16

Harriman couldn’t wait for them to find out. A week before Thanksgiving in 1903 he decided to tour the cutoff and surprised everyone by inviting a party of newsmen along with the usual cadre of rail officials. On Thanksgiving Day he led the large party onto the cutoff, where they poked around and posed for an endless array of photographs. In most of these pictures Harriman occupied an inconspicuous corner, as if he had wandered into the affair by accident. The occasion was a great success, but freight trains did not start running over the Lucin cutoff until March 1904.17

Gradually the sinking slowed, then stopped everywhere except at the two worst spots. Bear River finally held firm after one last disheartening drop of eight feet, but Rambo defied every attempt at taming. During the 287 days after April 1904, no less than 482 settling incidents occurred, 84 in August alone, 7 in one day, all in different places. Bizarre rumors persisted of locomotives being swallowed by the lake or of disastrous settlings. A sense of humor was needed to cope, but humor was not Kruttschnitt’s long suit. He chased and crushed every rumor with grim determination, as did Hood, who grew weary of denying the “bottomless pit” theory so popular with reporters. When freight trains finally began running over the cutoff in March 1904, Hood balked at letting passenger trains test the new line until the sinking had stopped.18

The thought of losing a passenger train to Rambo filled everyone with horror, but the longer Hood delayed sending the trains over the cutoff, the more newspapers babbled ominously about lack of confidence in the work or floated new rumors about gigantic sinks. The operating department was eager to take responsibility for the trains, and even the cautious Kruttschnitt was ready to let passengers enjoy the glorious view over the lake. In September 1904 Hood finally agreed.19

Not until December, after receiving seventy thousand carloads of fill, did Rambo finally surrender. On January 1, 1905, the operating department formally took charge of the cutoff, but Hood placed a hundred cars loaded with rock on a nearby siding for emergency use and insisted on strict speed limits across the lake. By then the weary engineers knew what had become of all the loose fill they had poured into the lake: gradually it had coalesced into small islands or bars. One engineer, showing the work to a lady friend, heard her exclaim, “How fortunate it was that you found those little islands!”20

Celebration: E. H. Harriman and his guests at the Lucin cutoff opening ceremony. The front row includes J. C. Stubbs (left, holding overcoat with foot on rail), Julius Kruttschnitt (with hankerchief in pocket), William Hood, the Southern Pacific engineer who oversaw the project (behind Kruttschnitt’s left shoulder), H. E. Huntington (straddling the rail next to Kruttschnitt), and Horace Burt (second from right, with beard). Harriman is the inconspicuous figure at far right clutching the post. He has removed his glasses for the picture. (Union Pacific Museum Collection)

“Found them!” he groaned. “It took us two years to make them!”21

The Lucin cutoff soon established itself as one of the wonders of the West. One engineer hailed it as “perhaps the most noteworthy engineering achievement ever attempted in bridge and fill work.” The ten passenger and fourteen freight trains that rumbled over it every day saved up to seven hours on their schedules along with the reduced costs of a straight, level route. The cutoff was more spectacular than some Harriman projects, but it fit one basic criterion: the savings paid for the cost many times over.22

Harriman’shared the feelings of pride and exhilaration. “I am delighted with this piece of work,” he beamed, “which I consider is almost unparalleled.”23

Work on the Southern Pacific followed the Union Pacific model closely. On any project Harriman’s first question was always whether the proposed plan was the best that could be devised. Once recovered from their shock at this largesse, Southern Pacific officers learned quickly to give Harriman what he wanted. Shoulders were widened, heavier rail laid, more ballast put down, and extra siding added. The busiest portions of the line were double-tracked; heavy iron bridges replaced wooden or light iron ones, new buildings went up, and 1,213 miles of block signals were installed in six years. A larger, heavier fleet of engines and cars replaced older equipment and raised the average tons hauled per train 51 percent between 1901 and 1909.24

But Harriman did not remain a slave to the Union Pacific model. He understood that certain peculiar features of the Southern Pacific required a different approach. It relied on oil to fuel locomotives, for example, because coal was scarce and expensive in the Southwest. To ensure supplies, Harriman expanded storage capacity, bought oil fields, and organized a subsidiary oil company. He also pushed to convert key roads to electric power, which offered a cleaner, more reliable source of energy in an age when the diesel engine had yet to be perfected for railroad use.25

Technical innovation always fascinated Harriman. In 1903, while touring France with his family by automobile, he wondered why some version of the vehicle could not be adapted to rails as a commuter car on lines lacking enough business to warrant full train service. On his return Harriman put his chief mechanical officer, William R. McKeen Jr., to work on the project. The enterprising McKeen came up with a self-propelled vehicle powered by a gasoline engine that could do forty to sixty miles an hour on sustained runs at lower cost than steam- or electric-powered cars. First tested in March 1905, the car evolved in little over a year to a model nearly twice as long with sealed porthole windows that kept out the weather and allowed stronger body construction.26

Harriman had this car sent east for a trial run over the Erie. At Arden he climbed aboard for the last leg and chatted freely with a reporter who called it a “submarine on wheels.” Encouraged by the results, the Union Pacific installed the cars on regular routes throughout the system. For more than a decade the McKeen cars prospered, then fell on hard times after World War I. Nevertheless, Harrimans vision left behind an imposing legacy. Thirty years later the McKeen car became a design inspiration for the train that revolutionized rail travel: the streamliner. And the Union Pacific leader who developed this new train in the throes of the nation’s worst depression was none other than Averell Harriman.27

Harriman resisted building branches on the Union Pacific, but he added considerable new track to the Southern Pacific. Following a principle he had embraced during his Illinois Central years, he often picked up existing roads and improved them. An earlier generation of rail leaders bought derelict roads just to get rid of the threat they posed, only to find themselves saddled with useless track. Harriman was far more selective, grabbing small roads that could improve his main line or feed it profitably and then bringing them up to his standard. If no lines existed in a region needing branches, he built as a last resort. Most of this work took place at the opposite ends of the system: northern California-Oregon and Texas-Louisiana.28

The most ambitious of these projects expanded the Southern Pacific’s position in Mexico. Harriman had long been interested in Mexico and had sent a man there to gather information as early as 1899. The Southern Pacific had ventured into Mexico a year earlier, when Huntington leased the Sonora Railway, which ran from Nogales on the Arizona-Mexico border to Guayamas on the Gulf of California. He then bought up large parcels of undeveloped coal land in the state of Sonora and talked of building branch lines to mine coal for the energy-starved Southwest.29

Harriman lost little time reviving these plans. In February 1902 he took a special seven-car train on a trip to the Southwest and Pacific Coast that lasted four months. One of his first stops was Mexico City, where he met President Porfirio Díaz and leading members of his government. The timing of Harriman’s visit was not accidental; Paul Morton of the Atchison was also in town paying calls at the palace. Nor had Harriman come merely to pay his respects. He looked at several roads with an eye to taking them over, then sat down with Díaz to negotiate for concessions to extend the Sonora road. His persistence brought two plums in the form of rights to lay new track up the Yaqui River valley to the mineral region Huntington had coveted and down the coast from Guayamas to Guadalajara.30

The Mexican venture turned out to be the largest new project undertaken by Harriman. After the work began in earnest in 1905, the Southern Pacific laid more than eight hundred miles of track in four years. To reduce costs, Harriman ransacked the globe for materials—importing ties from Japan, rails from Spain and Belgium, coal from Australia, machinery from Germany, and laborers from Russia, China, and Japan to toil alongside native Yaqui Indians. Harrimans strong sense of patriotism did not extend to paying high prices for materials he could get cheaper elsewhere.31

This was something new to railroading. No one had ever drawn from so wide a variety of sources for construction materials. Once it was completed to Guadalajara, the Southern Pacific owned the longest continuous line of railroad in the world, 3,750 miles of track stretching from Puget Sound to the Gulf of California. And there was talk of it growing still longer: in 1909 rumors swirled that Harriman might lay track all the way down to the Isthmus of Panama.32

The obsession of our own age with airplane crashes had its counterpart in the railway era, when headlines screamed lurid details of every major train wreck. During the early years of the century those headlines occurred with grim regularity as the number of accidents soared to record heights along with the amount of traffic. Between 1898 and 1908 an average of 363 passengers, 3,166 employees, and 5,661 other persons* lost their lives every year. But the averages were deceiving because the casualty count rose steadily to a peak in 1907, when more employees (4,534) and passengers (610) were killed than during any other year in American history.33

Railroad managers tended to duck the subject of safety because it was a public relations nightmare. Those who think that airlines hold a monopoly on grisly stories need only look at old accounts of people roasted alive in burning coaches or mashed in the impact of a rear-end collision or plunged to watery graves off a bridge. Pinning down responsibility became a familiar form of shell game. Rail officials blamed accidents on the negligence of employees; the unions charged them to faulty equipment, mismanagement, or overwork. Congress as usual talked much and did little on the subject. Railroad managers did not even care to talk, preferring a conspiracy of silence for two reasons: the negative effect on public opinion and their fear of liability suits. But they were hardly indifferent to the question. Good officers demanded safe operations and spent money willingly to get them.34

Of all the rail leaders who cared about safety, only one was fanatical in its pursuit. Harriman modernized a railroad’s approach to safety much as he did its physical condition. Between 1898 and 1907 his roads invested nearly $12 million in improvements directly related to safety. No western system spent more money on maintenance, and no system anywhere installed more automatic signals, which were expensive to put in and keep up. But money alone was not enough. The best equipment and strictest rules did little good unless the men had the right attitude toward them.35

Early in 1907 a series of ICC reports on 448 railroad collisions revealed that 65 percent of them had been caused by the neglect of crewmen. The crush of business after 1900 dried up the labor pool, leaving every road short of skilled workers and forcing them to hire men whose “zeal and fidelity,” as one trade journal complained, “seem to be waning.” Shippers and travelers did not help by sending mixed signals. On one hand, they clamored for safer conditions; on the other, they demanded faster schedules.36

Harriman tried to attack this problem through sheer force of will. Nothing infuriated him more than accidents caused by carelessness or negligence. He spurred officers not merely to wage safety campaigns but to hammer at prevention and slap harsh penalties on those who disobeyed rules as an example to the others. After one collision caused by the failure of a flagman to protect a stalled train during a blizzard, Harriman wired Burt angrily, “Something must be done to enforce the Company’s regulations [and] someone who has force of character should be put on this particular matter, and see that the rules are carried out.”37

Sometimes he delivered the message firsthand. On one inspection trip his train hit some rough track and nearly derailed because a work crew had failed to post a flagman. Harriman was livid when he learned the details and ordered Burt to fire the entire crew. “That’s rather cruel,” Burt protested. “Perhaps,” retorted Harriman, “but it will probably save a lot of lives. I want every man connected with the operation to feel a sense of responsibility. Now, everybody knew that the man hadn’t gone back with the flag. They could see it. And if he’s responsible, that sort of thing won’t happen again.”38

Harriman demanded full accounts of every accident and its causes as well as monthly summaries. Any serious mishap sent telegrams flying at Burt. “I wish it were possible,” sighed the hapless president after one collision, “to inspire operating force sufficiently to avoid accidents of this kind.” Harriman decided to show that it was possible by challenging an industry taboo. For decades railroads had dealt with accidents by whitewashing them for public consumption, mainly to avoid suits. In the process officials often deceived themselves as well. “The evidence is often made to substantiate a preconceived conclusion,” complained W. L. Park, “[and] the… testimony is shaped to meet the well-known views of a superior.” The result soon became a way of life in the age of bureaucracy. The “science” of railroading, snorted Park, was “the art of shifting responsibility.”39

Harriman wanted no more of it. In 1903 he set up boards of inquiry to investigate the cause of every accident. Four years later, with the accident rate soaring, he announced a bold new experiment: men of local prominence from outside the rail industry would be added to the boards and participate fully in the inquiry. The process would be opened up to public scrutiny to make the findings more credible. Kruttschnitt, who was himself a bear on the subject, admitted that civilians knew little about the composition of boiler plate or the intricacies of dispatching, but that was beside the point. “Whatever we do get in these reports,” he stressed, “we will get no whitewashing. We will get the responsibility put squarely where it belongs.”40

The legal department shuddered at the prospect, envisioning a steady parade of bogus damage and personal injury claims by every shyster in the West. But the reverse happened: an open inquiry left no mysteries or dark corners to explore. The public applauded the idea, and Kruttschnitt made sure the boards produced results by demanding that some cause be found for every accident. When the results fell short or were challenged, a second board was convened.41

These efforts made Harriman the undisputed leader in safety. While national figures continued to climb, the accident rate on Harriman’s roads dropped sharply. No other rail leader left a greater mark on this sensitive area. After his death, Mary Harriman perpetuated the legacy by endowing a safety medal to be awarded by the American Museum of Safety. The Harriman Medal could not have had a more apt name.42

The men who worked for Harriman regarded him as fair if demanding. His rumpled, unassuming appearance and eagerness to talk to anyone with something to tell him impressed them, as did the fact that he knew his stuff and never put on airs. But no one got close to Harriman; he was too curt and imperious. The loyal Bancroft tried to portray him as beloved of the employees, but he was more admired than loved. One critic described him as “a singularly unemotional man, even among financiers.” Another called him “cruel, hard, cold … full of strange contradictions, traits of real greatness mingling with traits of meanness and littleness.”43

There was also a tender side to him that few people saw. Dr. E. L. Trudeau never forgot the night his son died, when Harriman dropped all other business to sit up with him and then arranged special cars to carry the body and mourners to the funeral at Paul Smiths. Or the time in 1902 when Trudeaus health broke down and Harriman’sent him to California for two months, or the hunting and fishing club that Harriman and other friends sustained just so the doctor could use it. Utterly naive about business matters, Trudeau once asked Harriman if he would like to invest a few thousand dollars to add to the club’s wild land. “It seems well worth the money to me,” Trudeau said earnestly, “but you must decide, as I don’t want you to get ‘stuck.’”44

A huge, impish smile lit Harriman’s face. He touched Trudeau’s arm and said, “Ed, don’t you ever worry about my getting stuck.”

One Christmas Eve Harriman was confined to bed after a painful operation. Despite his agony, he summoned Southern Pacific auditor William Mahl and insisted on dictating a list of Christmas presents to be sent certain officials along with a letter thanking them for their loyalty and service. At the same time he decreed bonuses for the New York office staff equal to 10 percent of their salary. This was a revelation to Mahl, who had never seen Huntington do any such thing, and he marveled that it was Harriman, “a stranger to the Southern Pacific Company who in his humane character did for the employees of that Company that which was neglected by any of the four men in whose fortunes they had been instrumental in no small degree in building up.”45

Harriman treated the men in the ranks well because it was the right thing to do and it was also good business. Sometimes he had to be shown the way. Once he asked W. L. Park to buy a safety shaving set for him. Park found one that was rather expensive, and when he said that it cost $15.75, Harriman examined it closely and remarked, “This is much better than the one I use. I had intended it for one of the boilermakers in the car ahead, who was complaining that he had had no opportunity to shave himself since leaving San Francisco. I guess I will keep this and give him mine.”46

Harriman paused and looked quizzically at Park. “What would you do?” he asked abruptly.

“If I were going to give the fellow anything,” suggested Park, “it would be something his grandchildren would talk about.”

“I guess that’s right,” conceded Harriman. He snapped the case shut and ordered the steward to take it forward.

In an age when workers had virtually no benefits from either company or government, Harriman was among the first to introduce a pension plan on his roads. He helped put one into effect on the Illinois Central in 1901, when only four other railroads had plans, and the following year approved a plan for the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific systems. Modest as the pensions were, the men came quickly to prize them. One old veteran, clutching his first check, wrote in a wavering hand, “It is a noble thing for the Company to do.”47

Other programs tried to serve the men still on the job. Like most railroads, the Union Pacific had long had a hospital plan, and some unions had organized their own relief plans to aid men and their families in times of death or injury. Harriman wanted something more—a program that would help bright, ambitious workers advance through the ranks. From this premise flowed the idea of creating a system to train men at all levels for any work they wished to learn.48

The plan took time to evolve; not until 1909 did the Union Pacific create its novel Bureau of Information and Education. Most major railroads provided special training for different classes of employees, but none extended it to all workers wishing instruction. The bureau offered training at company expense in any area and created a separate board to answer inquiries on any aspect of their work. Its programs aimed to improve efficiency, keep men abreast of new methods and technologies, and target promising candidates for promotion. Nothing better exemplified Harriman’s desire to lead the industry into the new century. He created the first direct challenge to the tradition of older hands teaching younger ones to do things the way they had been taught.49

In his domineering manner Harriman was the same father figure to his rail workers as to the inhabitants at Arden: stern but just, demanding strict obedience and close attention to duty in return for good pay, decent working conditions, and other considerations. But Arden was a closed world without unions or a work force wildly divided by rank, skills, and ethnicity. Every railroad found it difficult to keep a stable work force, and the record flow of traffic wore down men as fast as it did equipment. Even the modernized Union Pacific-Southern Pacific systems struggled to handle 50 percent more business than their capacity.50

“The car shortage is worse than ever before,” observed Kruttschnitt, “but the real trouble is to get labor.” The influx of newcomers created a volatile mix of rookies and veterans just when peak efficiency was needed to handle the deluge of traffic. Rail managers complained that the shortage of labor made it impossible to impose discipline on the men, which meant more accidents as well as more labor strife. Sometimes workers resisted attempts to improve productivity. When this happened on the Union Pacific, Harriman found himself with a fullblown crisis.51

In June 1901 Harriman gave Horace Burt approval to convert the shops to piecework. The machinists, boilermakers, and blacksmiths promptly walked out. Burt managed to hire enough new men to keep the piecework system running. That winter he patched together an agreement with the strikers, but in June 1902 the boilermakers demanded a pay hike as well as rule changes. When Burt refused, they struck again and were followed by the machinists and blacksmiths.52

Neither the carmen, who made up half the work force in the shops, nor any other unions joined the strike, yet the strikers held out stubbornly month after month. An official warned that the fight meant “a great deal of money, to all of the Harriman lines; if we lose it, we practically lose control of the shops.” Burt was so convinced of this that he staked his reputation on the outcome. Harriman gave him a free hand to deal with the crisis. Unmoved by the prolonged struggle or sporadic outbursts of violence, Burt took a hard line. In January 1903 the union men demanded the abolition of piecework. Burt replied curtly that they would never again work on the Union Pacific except under the piecework system.53

So far the road had kept up repairs well despite the strike, but the crush of traffic kept increasing the demands on equipment. The unions then threatened to hit the Southern Pacific, where Harriman already had problems. He loathed the idea of backing down on a vital issue, but his options were running out. In June 1903, two years after the strike began, he agreed to gradual withdrawal of the piecework system and a 7 percent pay hike for the shopmen. Under the agreement, the nonunion men, who by Burts count made up 73 percent of the shop force, continued to do piecework, but when Harriman visited Omaha that September, the union leaders complained that the system was not being scrapped as promised. Reluctantly Harriman ordered it abolished.54

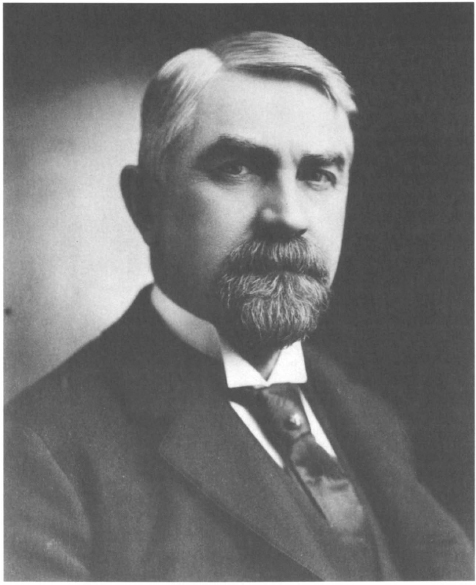

The first president: Horace G. Burt, first president of the reorganized Union Pacific, who resigned after repeated clashes with Harriman. (Union Pacific Museum Collection)

This was a rare retreat on Harriman’s part, and it cost him dearly. A humiliated Burt turned in his resignation that same night. The nonunion shopmen, feeling betrayed, left the company or drifted into the unions. Harriman had hoped for greater efficiency; instead, he helped the unions entrench themselves more solidly than ever in the shops, setting the stage for later, more bitter battles.

Harriman understood that the future could not be based on the past. He agreed entirely with an editor who observed, “We cannot restore the conditions of 30 years ago, when so many managers were personally acquainted with their employees, therefore the only alternative is to increase the efficiency of the deputy managers.” In his desire to create a new railroad, Harriman realized that he needed not only a new type of officer but also a new kind of organization.55

* The “other persons” category refers to accidents that do not involve trains or their movement but occur in shops or elsewhere on site. It is revealing that the public furor over railroad accidents ignored the fact that far more people were killed in nontrain accidents than in mishaps involving trains.