Shatin to Shataokok

Traffic on the road became very spasmodic, and finally stopped altogether. Then, when all was quiet, I stepped on to that perfect highway and set off at a fast pace, revelling in the speed and the smooth comfort. Almost at once there were houses at the edge of the road, and I stepped lightly, making no sound with my bare feet. This was the village of Shatin.

Buildings crowded close along the roadside and lights shone from open doors and windows, but not a soul was stirring outside and I took a chance that in retrospect seemed to be the height of folly. Stepping swiftly and silently I walked straight through the village, through the beams of light from the doorways, looking in at Chinese families busy at their household chores. A few short minutes took me through, and I was swinging along a silent deserted road, my spirits bubbling over with the pleasure of this easy progress after the pain and effort of the four previous nights. The alternative to passing through Shatin was to make a detour of perhaps a mile over unknown terrain, and the temptation of the road was too strong to resist.

A slight delay occurred at the railway station. Bright lights covered the road from a veranda on which sentries were stationed, so I climbed to the tracks, hoping to be able to pass on that side. But lights flooded the railway lines too, so I crept up to the end of the station to listen to what was being said. Several Indian guards were inside, and someone was speaking in English. Unfortunately the voice was too muffled for me to follow, the only words that came to me clearly being “Shamsuipo … Japanese … fifty yen.” The mention of Shamsuipo made me wonder if they were discussing my escape, but my ego would not allow me to believe that a reward of only fifty yen, about £3, 10s., was being offered for my capture.

Moving away beyond the range of lights I crossed the road climbed down a bank and passed the station over the paddy fields. Then I enjoyed a splendid walk of several miles over a perfectly level highway that followed the shore. Where this road turned inland it crossed the railway lines, and there a sentry was on guard. It was one of the rare times when stars were shining; as he was visible for some distance there was no chance of slipping past unseen. Leaving the road I intended to climb over a ridge and so pass the crossing, but the track became more and more difficult and I could find no way down the steep banks. I went back across the road, scrambled down to the sea, and waded for some distance before deeming it safe to return to the road. Heavy showers fell with increasing frequency, but I was enjoying the smooth going and when the road began to rise inland I climbed and climbed until it seemed my heart must burst. What felt like violent explosions took place inside my head, and after the second one, which almost made me fall, I stopped to rest beneath a large tree.

From that vantage point I had an extensive view across Tolo Harbour, and the lights of the fishing fleet made a most pleasing picture, especially to eyes so long confined to the limited scene from the camp. Hundreds of craft were there with one or two bright incandescent lamps on each, and, with reflections added, the whole made up a fairy city twinkling in the black expanse of the bay.

Starting off again I soon topped the rise, and began a long easy descent. The slopes of Tai Mo Shan rose steeply from the left of the road, and many streams came tumbling down to afford a plentiful supply of drinking-water. My water-bottle was nearly empty, so I decided to fill it at the next accessible place. It was then that the fireflies gave me their first assistance, the first of three encounters with those brilliant little creatures, which are events bordering on the realms of fantasy.

No access could be found to the next two streams, and then I came to one which tumbled down some distance from the road. That one was guarded by thick scrub and tangled thorn-bush, and, while seeking an entrance I noticed many fireflies passing me, going a short distance along the road, and then turning in towards the water. So many were flying the same course that I decided to follow them, and sure enough, they were turning in over a track that led to a waterfall. Having filled my bottle I went on my way, musing over the usefulness of those unexpected allies, for as it happened, that was the last place at which water could be had.

Continuing on my way I came to a railway crossing, and beyond that there was a long bridge that ran directly seaward. There was no indication of any such bridge on my map, and since the night was far spent I turned back and climbed to a ridge from which to view the scene by daylight. Perfect cover was available on a level spur two hundred feet above the road, and I settled down there, feeling very satisfied with the night’s work.

Full day brought a very pleasing view, but it was bad luck that the road disappeared behind a high headland no more than half a mile distant. After the railway line crossed the road at the intersection reached on the previous night, it immediately plunged into a deep cutting and also disappeared from sight. Directly before me, perhaps four hundred yards from the railway embankment, there was a small island from which a causeway ran westwards. The road was carried on a long bridge to that causeway, and at the junction there was a Japanese guard-post, where all vehicles and pedestrians were being stopped and searched. There was no sentry at the rail crossing.

Taipo Market was not in sight, but I knew that it must be very close and could only assume that it lay directly behind the hill that blocked my view. The island and causeway formed a sheltered bay into which all day long there came a stream of junks and sampans, the smaller vessels lowering their masts and proceeding under the bridge to a more sheltered haven inside. It was while watching those little ships coming to anchor that I decided to steal a sampan that night and proceed across Mirs Bay by sea, and so cut out many miles of dangerous travel. Most of the junks had a sampan towing astern, and there were several others hauled out on the island.

My pocket-knife was too blunt to cut a rope swiftly, so I bound a razor-blade into a split stick. That occupied an hour or more, and then there was nothing more to do except wait for night. Traffic was constantly moving on the road, chiefly coolies with heavy loads on their shoulder poles, and it did not cease until it was fully dark. Occasional late-comers passed, so it was not until another hour had gone by that it was safe to move. Then I went down the road to the railway crossing, and walked back along the lines to put my plans into operation.

A smooth concrete wall sloped steeply to the sea, so, when opposite the junks which were anchored farthest out, I passed my rope round a telegraph pole and slid down to black rocks below. No thought of having to regain the road entered my head at that time, so I pulled my rope down. Stripping off my clothes I left them with pack, water-bottle and rope, and swam out into the bay. The razor-blade knife was between my teeth. Not one of those sampans held an oar or anything else that could be used as a paddle. One after another yielded the same result, so I continued to the island to carry out another fruitless search there. There was not a stick or board anywhere in sight.

By that time it must have been near eleven o’clock. It was raining steadily, a fresh wind was blowing, and I started to shiver violently. There was only one way to cure that, so finding a sheltered place I indulged in a few minutes of strenuous physical exercises to start my blood flowing again.

The search for a sampan having failed, I then decided to try to beg a passage across Mirs Bay in one of the junks. They were all vessels that plied about Hong Kong, and I hoped that someone on board would understand at least a smattering of English. Wading into the sea again I swam quietly to the junk farthest out, and consequently farthest from the guard-post, and floating close alongside I began to call softly to the owner. At last a sleepy voice made some reply, and a figure rose in dim silhouette against the dark sky. While I stated my needs as simply as possible the owner was peering down at me, but before I had finished he suddenly began to shout, to jump up and down, and to shake his fist at me with every indication of fierce hostility. In my most persuasive tones I tried to quiet him, but my efforts only increased his agitation, and an attempt to climb on board brought me a narrow escape when he made a vicious crack at my head with a piece of timber.

The increasing clamour made me fearful that the guard on shore would be roused, so I had to go. Brilliant phosphorus lit me like a flame as I swam, and, when passing close to another junk her crew opened an attack upon me with chunks of wood. Four or five men on board had been roused by the shouting of the first junk owner, and in addition to their bombardment they also raised their voices with threatening shouts. The situation was becoming serious, and I was torn between the desire to get out of range and the need to slow down so that the phosphorus would not disclose my position. Any one of those heavy blocks could have knocked me out, but, after being straddled several times without suffering a direct hit the ammunition all fell behind me, and I went as hard as I could for the railway embankment.

Luckily my sense of direction had been fairly good in the dark, and I soon found my gear. By great good fortune there was a wire-stay from the pole to a bolt embedded near sea-level, and using that to haul myself to the top of the embankment I stopped only long enough to realise that a great deal of shouting was arising from the bay, and bolted along the railway to cross the road before the guards were roused.

Almost at once I plunged into the impenetrable gloom of a deep cutting, and, hearing someone approaching, I pressed hard against the bank. The man collided with me as he passed, and he rushed off, evidently receiving as big a fright as I. He was probably a smuggler using the railway to dodge the guards on the road, and he would certainly have been shot had he been found there by the Japanese.

On rounding a bend I had a clear view back over the bay of my unsuccessful adventure, and there was a great uproar in progress, with lanterns flashing everywhere. My nocturnal visit had certainly started something, and vowing never again to seek assistance as long as I could still walk, I hurried on my way.

A high bridge carried the railway over an arm of sea, and my first few careful steps on that structure, not being quite careful enough, almost ended in disaster. The footways had been removed from alongside the rails, and a pedestrian had to step over the sleepers. Occasionally a sleeper was missing, and suddenly there appeared a space where not one but two sleepers were missing. My weight was already going forward, and, not being prepared for such a wide gap I just managed to throw myself sideways and grab a rail in falling.

The experience gave an added jolt to my already somewhat tattered nerves, and from then on I proceeded warily on hands and knees, for the water seemed to be a long way below and gaps in the sleepers were both frequent and irregular. On looking down I thought that there was a straight canal there, separated from the sea by only a narrow bank with a row of trees on it, but on taking a second look in a lighter period between showers I saw that it was a road, not a canal, that lay there. Once again a wet and shiny surface was giving the illusion of water. That being so I erroneously reasoned that the bridge would take me to the wrong side of the estuary, and I began a laborious return.

Once back on solid ground it did not take long to find a track leading down to the road, but that was no highway, for it soon narrowed to little more than a track beside the sea. That was very disappointing, and I made my way back to the railway. My mind seemed to be fixed on the idea that the road should be on that side of the estuary, so instead of making another attempt to cross the bridge I walked back along the lines. There the railway was carried on a high embankment, and I could find no way down until fireflies again came to my assistance. Many of those bright little sparks began dancing along, following the same course, and after going some yards ahead of me they dipped suddenly down over the edge of the bank. It was a real game of follow my leader, and, having joined in, I found that they were turning off at the start of a narrow track. It was no more than nine inches wide and barely discernible on the hard ground, so it was a mystery why the flies should choose to wing their way directly above it.

Reaching a tarred road of good surface I soon passed an archway through the embankment, noting it in case of future need, and continued until hemmed in by buildings. A narrow path lay alongside a large brick or concrete structure, and I advanced with the utmost caution, my bare feet making not a sound. At the top of the lane there was a wide roadway, and turning left I climbed carefully but quickly up a steady incline. Just as the road levelled off I stopped stock still, every nerve in my body tingling, for not more than eight feet to my right the luminous face of a wrist-watch was glowing.

A moment later a man on my left began to speak softly, and there, about twelve feet away, was the faint silhouette of a sentry. My first thought was that he must have been speaking to me, but apparently he was addressing the man with the watch. Slowly I began to back out from between the two guards, expecting at every moment that a torch would flash upon me. Nothing happened, the voice continued steadily, and as soon as I was well clear I turned and bolted down the narrow lane from which I had so recently emerged.

In my official report that incident was described as having taken place at a crossroad, but after the war I saw that I had actually walked up to the entrance of Taipo railway station. The sentry with the watch was posted near the top of a narrow flight of steps, the talkative one was posted at the gate. The Taipo station at that time was occupied by the Gendarmerie, so my luck may be imagined when it is remembered that I had already passed it twice on the railway, before making my frontal assault on the building. All of that folly was occasioned by the intense darkness and my complete ignorance of the locality.

My next adventure occurred when, having returned to the archway through the embankment, I decided to go through and try my luck on the other side. Exactly what happened next will never be known to me. My belief was that the arch opened out into a large storage space, that I could smell rubber and petrol, and that people or animals were there, breathing and moving in their sleep. That was my impression. Sounds of loud breathing made me stop dead, not knowing what to do. Behind me every avenue of escape seemed to be blocked, so believing that it was no more dangerous to proceed than to retreat I went on again, and shortly emerged among the buildings of a village. My next clear impression is of climbing up a steep concrete road thinking that at last I was on the highway, only to find that it was leading to a private estate which was closed to prowlers by large and handsome iron gates. Nothing could be gained by climbing in there, so I descended the road for a little way and then climbed to a ridge, where, feeling utterly exhausted, I sank down to await the dawn.

It had been a night crammed with adventure. First there was the abortive swim among the junks which almost ended in disaster; then there were the dangers on the bridge, the escape from the sentries, and the eerie passage through the railway arch. It was no wonder that I was feeling haggard and worn.

When I tried to go over my route in September 1945 I could not learn what had happened in my wanderings about Taipo. The arch through the embankment was just a plain bare archway, but directly opposite it across a very narrow lane there was the permanently open entrance to a large house. My conclusion is that I must have walked through the arch and continued straight through the house, there hearing the people breathing and moving restlessly. Be that as it may, the fact remains that I could not find the roadway up the hill or the large iron gates, nor could I discover where I had climbed to the ridge above. What is more, although there is no doubt that I went through the arch and into the village, during my later inspection I could find no possible route from the village to the position on the ridge where I found myself the next morning. That is a small section of my life on which my mind is a complete blank.

Mercifully the day was not long in coming, for fierce squalls roared through the bushes about me, torrential showers were falling, and in spite of the high summer temperature I was shivering with cold. Full daylight revealed the road on the far side of the estuary, so most of my troubles had been caused through returning from the bridge instead of crossing over. Three or four miles away a spur running down from Tai Mo Shan cut across the head of the estuary, and as there could be only a narrow stream at that point I decided that a crossing there should be easy.

A full typhoon was blowing, and squalls of wind and rain were driving across the landscape with all the ferocity that such storms can bring. A hurtling sky dragged tenuous grey veils low down across the mountains, and all normal work was suspended. The paddy fields in sight were deserted, and no one was abroad. I was on a ridge devoid of habitation or cultivation, and in the circumstances it seemed to be safe enough to go on my way, using the contour of the land to shield me from houses and villages. My intention was to go down the spur which ended near the road, and to reach that objective I had to climb high up the side of Tai Mo Shan, above the villages and paddy, and there cross several intervening valleys and ridges.

The wind was terrific, and clouds of small pine tufts, torn from a grove on the lower slopes, went flying across the ridges. Squalls drove me running in efforts to keep my balance. It was tiring work climbing and fighting the wind, and I was very glad to rest in the shelter of some large rocks which offered a haven of refuge in the driving onslaught of the storm. Not a soul was in sight anywhere, and after resting for a few minutes I set off again in a lull between showers, and climbed steadily until the highest of the paddy was a long way below.

As I climbed, the valleys became narrower and the traverse shorter, and soon I began to look for the right place to cross – the point at which farther climbing would entail more effort than the crossing.

There were fierce little torrents rushing down the mountain, and the gullies in which they ran were filled with small bushes. Those gullies were deceiving, for, having started to cross the mountain-side I found them to be much tougher obstacles than I expected. A space from fifty to one hundred and fifty yards wide was filled with dense growth, thickly tangled with thorny creepers. It was very slow work pushing through those barriers, and when I did reach the rushing streams I jumped in and let the solid water pour over me.

For six days and nights rain had been pattering almost constantly on my bare head, and it was with feelings of exultation that I held my breath and buried my head in the water. It was grand to feel the torrent roaring over me, and the stream felt much warmer than the wind and the rain.

There were three such valleys to be crossed, and it was late afternoon before the last of the clinging vines had been left behind and I began a long descent. The storm had subsided, and, as there were tracks to follow most of the way, progress was swift and easy. Of course my feet always pained more going down hill, for there was no skin left under or between my toes, and almost half the ball of each foot was devoid of skin also. However, the pain from those merged in the general ache and pain which signified my feet, and it did not unduly delay me.

Half-way down, the track began to skirt the top edge of pineapple plantations, and though it was too early in the season, the sight of freshly peeled skins made me keep a sharp lookout for fruit. Nearly a mile of those plants yielded nothing, and then, just before dusk, I saw a small green pineapple, not far in from the edge. Although it was a very immature specimen it tasted remarkably sweet, and to my disordered palate it was delicious.

Having quickly disposed of that all too meagre meal I continued to the rim of the final declivity, and saw a most satisfactory scene below. Beyond a flat of paddy a track led from a village to a narrow unguarded bridge across the river, and there was my road, hard by the far end of the bridge. The day’s work had been well worth while, and I lay back to rest until evening shadows deepened. Before it was quite dark I went down and across one of the irregular winding tracks that led across the fields. The main path leading from the village to the bridge should have been easy to find, but the fields were very much wider than they had appeared to be from my resting-place on the hill, and when I finally reached the other side it was to emerge right in the village itself.

I tried several paths, each of which entered a labyrinth of buildings, and my position was not a happy one for many people were moving about, and several times I was forced to step aside to let someone pass. It was intensely dark beneath large trees which grew about the village, and after trying one path after another without success, I realised that my sense of direction was rapidly going astray. That was no place in which to be lost, so returning quickly to the open paddy I retraced my steps while there was still enough light to see the outline of the hill previously descended.

Greatly relieved to be back in comparative safety I forsook the track and skirted the foot of the hill, ploughing along through knee-deep mud and water. It was hard walking, and the paddy went on endlessly. I seemed to be in the midst of a boundless morass, and then, suddenly, I was up on a stone pathway and almost at the bridge.

No one was in sight, and a few swift steps took me across to the smooth level surface of the road. What a wonderful feeling it was, to be able to step out freely along the clear highway after the heartbreaking struggle on the mountain. My spirits rose tremendously as I set off at a steady pace along the road towards Fanling, and I am afraid that I was filled with more elation than care. So much so that, when trees along the roadside began to take on a pale ghostly light the reason did not dawn on me at once. When it did finally register I felt terribly conspicuous in the headlights of a car that was coming along behind me. Military vehicles were the only ones running, so I was very pleased to see it turn into a drive leading to a large house some distance off the road. The occupants had not noticed me, but it was with a more wary eye that I emerged from a hiding-place and resumed my journey.

Light showers were falling, but the wind had died away and soon stars were shining between the clouds. It was then possible to see much farther, and the sheen on the wet road brought trees and occasional buildings into dark relief. Old trees had originally formed an avenue along the road, but many of them were missing, and the gaps formed long stretches where there was no shadow. On glancing back at one of those open spaces I saw a stump standing in very clear silhouette, and thereafter I crossed to whichever side of the road offered the best background. When approaching the clear patches I had a good view of what was ahead, but where trees grew nothing at all could be seen, and it was not comforting to know that I would be in full view of anyone in the shadows. No doubt my fears were exaggerated through strain, but to travel at all on the only road was a very hazardous procedure, and there would be no second chance if I were once seen.

A shower passed; then the clouds broke and all the sky was studded with brilliant stars. There was nothing on the road, and I stepped along at a steady pace, highly pleased at the ease with which the miles went by. On the left of the road a clump of big trees made a black patch against the sky, and as I neared them a group of people came along. They were talking cheerfully and had obviously been making a social call, and I stepped among the trees while they passed. Almost at once the headlights of a car came streaming down the road. I stepped back behind a tree, and as the car went by I saw that it was filled with Japanese officers. When all was quiet again I went on until some buildings appeared a little distance to the right of the road. Several soldiers with lanterns were moving about, voices were raised, and someone was shouting orders. Very much on the alert I kept moving cautiously, and soon saw the railway lines crossing the road ahead of me. That was a point that might be guarded, and there was a small building that might be a sentry-box standing by the crossing.

The road ran along the top of an embankment raised eight feet above level fields on either side, and, slipping over the edge, I worked along the sloping bank until I reached the railway. That too was running on an embankment of the same height as the road, and the only way past was over the top. The sentry-box looked menacing, so moving away out of sight I went swiftly over the rails and down the other side. It took only a few minutes to regain the road, and my steady pace was resumed.

Intense darkness had settled down, rain was falling, and shortly there occurred an incident which savours of the miraculous. Did some movement catch my eye? Was there a slight sound? Nothing recorded on my memory except a sudden feeling that imminent danger lay ahead. I grabbed the base of a small shrub growing at the roadside and threw myself over the bank, holding on with my face on a level with the road surface. My feet had scarcely stopped sliding and crackling in the grass and shrubs, when the legs of a soldier went past only three feet from my face. He was the first of a patrol of six who filed silently by. They were wearing soft rubber-soled shoes that made no sound, and, as they were walking on my side of the road, had I continued for a few more paces we must have collided. The last man went past, and close on his heels was a large Alsatian dog.

There was intensity of drama, with my life hanging on the outcome. I neither moved nor breathed, and yet had a curious feeling of detachment as if my mind, removed to a safe distance, was able to concentrate its whole attention on the scene to be enacted. I felt no fear at all, but every sense was tuned to its ultimate degree of tension on what was about to happen.

The dog turned towards me, sniffing the air inquiringly. His nose was less than two feet from mine, yet he seemed to be at a loss what to do. There was only the darkness between us so surely he must have been able to see me. He was only too clearly visible to me.

He lifted his nose, laid his ears back, and there was a strange expression in his eyes as if he were trying to recall something from a long way off. His ears pricked forward again, and he seemed to be looking directly into my eyes. Then his head went down slowly, and he turned without a sound. With his tail drooping to the ground he loped off after the patrol, a picture of utter dejection. The men began to speak softly, and when their voices grew a little louder I thought they were coming back. But the sounds faded again, and all was silent.

Why did the dog neither growl nor bark? Did he know I was there, or did my presence fail to register on his senses? Some of my friends suggest that I was probably so dirty that the dog was mystified; others, of a more serious bent, suggest that a higher Power was guarding me. I leave it to you to ascribe your own reason, for my part I am content with the event. One thing is certain; and that is that prior to that experience no one could have made me believe that any dog, confronted with a similar situation, would have failed to make some demonstration.

It was my belief that the road should then be safe for some distance, so I set off at a good pace and soon came to a concrete road leading off at a right angle to the main road. On my very meagre map there was only one road going off to the right, and that was the road to Shataokok. However, that would be a very old road, whereas this one looked new and it was spanned by some ornamental archway. The Japanese had large camps in the Fanling area, and it was my guess that this was the entrance to one of them, and that it was from there that the patrol had issued.

Acting on that assumption I went on, and soon a road fork came in sight. There were white railings round the corner, and large trees on both sides of the road threw the whole area into deep gloom. Walking as silently as a cat I took the right-hand road. This went off at an angle of forty-five degrees, not at right angles as shown on the map, but after going some distance I felt sure that it was the right one, for thick old trees lined the sides.

Afterwards I learned that a guardhouse was located at the fork, but I walked right past without even knowing that it was there.

The night was far advanced and, though occasional buildings appeared, no lights were showing and no one was astir. Then the road ran along an embankment across miles of flooded paddy. It seemed to go on endlessly, and I was beginning to fear that dawn would find me out in that wide expanse, when the outline of hills came into view. Soon they were close about me, and thinking that Shataokok must be near I decided to climb a hill from which to view my surroundings in daylight. A hillside thickly grown with small trees offered a good prospect of cover, but there was no undergrowth so I kept on climbing to the top. There I found a clump of bushes large enough to crawl inside, and the sky was already growing lighter by the time my hideout had been made a little more comfortable. The rain had stopped, and it was a pleasure to be able to lie down at full length, for I had then been walking more or less continuously for two full nights and a day.

That was the seventh night of my journey, my clothes had been soaked the whole time, and sleep persistently eluded me. Never had I had more than half an hour of oblivion in any twenty-four hours since leaving camp. My tinned food, mostly used in the first few days to keep up my strength at that critical time, had all been consumed except for one tin of condensed milk. The remainder of my supplies consisted of soya bean powder, a tin of a heart of wheat cereal, a small bottle of peanut oil, and a small tin of black pepper. The pepper had been taken to drop along my tracks to discourage dogs from following me, but the continuous rain had made its use unnecessary. Instead of deterring dogs it was put to good use in flavouring my scanty meals.

Those were eaten twice a day, breakfast about sunrise, dinner just before dark, and each meal consisted of three dessert spoonsful of soya bean flour, two spoonsful of cereal, half a spoonful of peanut oil, a little water, and a flavouring of pepper. That mess was mixed diligently into a smooth paste, and it was surprising how appetising it seemed. The full meal occupied only about one inch of depth in a very small tin, so it was eaten slowly and with great deliberation. I enjoyed those meals immensely, while any addition to my diet, such as the pineapple, was extremely welcome, yet I had never at any time felt hungry. Presumably the stress of nervous tension in which I constantly travelled had ruined both my appetite and my ability to sleep.

A disappointment was in store, for with the coming of full day no trace of Shataokok was to be seen. A range of hills stood between me and the sea, so it was obvious that I had stopped some miles short of my objective. No more than half a mile away the road disappeared round a bend, my view was hemmed in by mountains, and as nothing could be done until night came I settled down to rest. A much higher hill rose steeply from immediately behind me and I kept watch for people moving there, but the whole place seemed to be deserted and I saw no one, either in the fields or on the road.

Towards noon the sun was breaking through, and it was most comforting to be really warm again. It was a good chance to dry my clothes, so I stripped and hung them out of sight among the bushes. Then my papers and diaries were spread about, and though they had been soaked for a week, the ink with which some of the papers were written had suffered remarkably little damage. Everything from which water could evaporate was hung out to dry, and even my current diary was brought out to air. That was carried in a plastic shaving-soap container, one which had originally been retrieved from a Canadian’s pack on the battlefield high up on Hong Kong’s Mount Cameron. In it were my watch, three razor blades, a short pencil, and several small sheets of writing-paper. The watch had a broken spring, but it was a gift of some sentimental value and I did not want to lose it.

Sleep would not be coaxed, and the day passed in a wakeful quietude so profound that I seemed to be alone in a deserted world. No sound of man or beast disturbed the silence, only occasional butterflies darted in swift flight, with flashes of brilliant wings. My sole tormentors were the pestiferous ants, which made every day a misery with their vicious stinging bites.

A survey of my feet and legs showed them to be in a sorry state. Every toe was burst, and the balls of my feet were almost devoid of skin. That condition was brought about partly by dermatitis, “athlete’s foot”, or any other name which indicates that virulent fungoid growth that eats its way between the skin and the flesh, causing the outer layers to peel off. In addition there were several deep holes caused by sharp stakes, there were cuts and scratches of varying size and depth, and there was scarcely any skin left on my shins. Thorny trailers were responsible for that. I do not know what the plant was, but it grew like a blackberry, the trailers running for yards through the grass. I was everlastingly sliding my feet under those in the darkness, with the result that their savage thorns tore across my shins, taking skin and flesh with them. Just for good measure my right hand was very sore and stiff. That was the result of the injury received when sliding down my rope over the sea-wall at Shamsuipo, and during the past nights the wounds had been aggravated by continued stabs from sharp branches and stiff grasses.

My only ointment was a small box of dubbin which was one of a consignment that the Japanese had for some unknown reason sent into the camp. Each morning I covered the sores with a thick coating of that grease, and apparently it was clean enough, for none of the injuries ever turned septic.

I still had my shoes, although most of the time they had been slung round my neck. I had worn them for only brief periods in the rough country behind Kowloon, and again when I waded in the sea past the sentry on the railway line beyond Shatin. On wet roads they would squelch loudly at every step and it was quite impossible to wear them there, for by going barefoot I could walk in complete silence. In that way I had passed close to many large houses and villages without once rousing a dog, in spite of the fact that every Chinese village is alive with curs of every breed and temper, mostly bad.

In the late afternoon I gathered my belongings and, after a meal, went down through the trees to a spot near to, though hidden from, the road. There some dry straw made a most comfortable bed, and a sound sleep claimed me for about half an hour. On waking I found that it was nearly dark, so, after waiting for another ten minutes I crossed to the road and went on my way again. The clouds had cleared away, and a bright new crescent moon shone in the western sky. The sight cheered me beyond measure, for a new moon shining in a clear sky is a most passionately optimistic symbol. Nothing transcends the promise diffused by the bright silver crescent, for each night it will grow larger and more luminously beautiful, more powerful to weave its magic spell.

The road turned in among steep hills, the moon sank out of sight, clouds obscured the stars again, and intense darkness engulfed me. Trudging steadily along it was difficult to concentrate on the road. In fact, my legs seemed to move automatically, and my mind wandered off at all manner of strange tangents, so completely detached from the immediate scene that I was walking as if in a dream.

Fireflies began to dance across the road, and soon they gave me their third and final help. Penetrating the mists that shrouded my mind there came the realisation that one of those bright little sparks was coming straight towards me. Glowing brighter as it came it headed straight for the middle of my forehead, and then, at the moment before impact, it skimmed up and away. Soon another followed the first, coming directly towards me up the road. This one seemed to glow brighter as it came, and at the last moment it too skimmed up and away.

Hazily I thought it strange that they should both follow exactly the same course, but they made no further impression until a third fly came bearing down towards me. I saw this one a long way off, and as it approached it grew in size and brilliance until it seemed that a blazing meteor was about to strike my forehead. At the last moment that one also skimmed up and over, but the repetition of the act, together with the amazing brilliance of this last visitor, shook me into consciousness. I felt it was a warning, not to be ignored, of some danger threatening from straight ahead. Concentrating all my faculties on the road I soon became aware of a luminous glow on bushes a little distance off on the right-hand side of the road. It was very faint, fading and growing brighter, and I was wondering what could be causing it when the bushes suddenly stood out in sharp relief. A car was swinging out of a concealed drive, and just as I flung myself full length into a ditch all my surroundings were flooded with brilliant light.

Had I been too late? The car approached rapidly, and, feeling extremely conspicuous on the snow, I kept my face buried in the mud as the vehicle went by. It had been a miss by a split second, and had the fireflies not brought me back to consciousness it is certain that I would have blundered on, full into those lights.

The road was descending, and soon occasional buildings showed. These became more frequent, and it was obvious that a settlement was near. I noted a worn path that left the road to disappear into fields, thinking that it might be useful later, and soon came to a picket fence. Beyond that there were solid two-storey buildings on either side of the road, the space between them intensely black. With all my senses alert I moved in between the buildings, but I had advanced only two or three yards into the dark when there came again that urgent feeling of danger. There was absolute and utter silence, and I stopped still in my tracks, straining eyes and ears for some hostile movement. Suddenly, with a crash, a rifle fell to the ground immediately in front of me, and the sentry was muttering as he picked it up. Once again some sixth sense had saved me, and, after backing away for several yards I turned and made for the track, previously noted, which led to the fields. That brought me to a village nestling at the foot of a steep rise, and I emerged on to a narrow pathway that ran along the fronts of the houses. Turning right I soon came to the end of the path, where there was a steep wooded bank on my left and paddy fields on my right. Across the fields lanterns were moving and torches flashing, and I knew that there lay the important market and fishing village of Shataokok. That was right on the boundary between China and the New Territories, and before the Japanese occupation one side of a long street had been under Chinese control, while the other was under British.

Since the roads were guarded I decided to skirt Shataokok, and, hoping to find a path that would lead inland I returned along the fronts of the houses. Extreme care was needed, for just inside several open doorways I saw the heads of people asleep. After one excursion up an alley which ended in a courtyard, I continued to the end of the village without finding any outlet. Somewhere among the buildings a dog began to bark in increasing agitation. Had he heard me? Was I the cause of his alarm? It might have been so, and since other dogs would soon be roused I must go quickly.

The dog was growing more and more excited, so I took to the paddy and waded silently away. Had he come after me my discovery must have been certain, and I was very glad when a safe distance lay between us and the barking died down. Making a wide detour I finally found another track which took me to a narrow, though well-formed road. As that led away from Shataokok and began to rise inland I knew that it must be a road, shown on my map, which followed closely the boundary of the New Territories.

From careful scrutiny of contour plans of this area I knew that the land rose steeply from the shores of Mirs Bay to the highest ridge, and then fell away in a gradual slope westwards. I decided to follow this road up to the ridge, and there cross the frontier into China before returning to the coast north of the village. All reports and rumours had indicated that Shataokok was heavily garrisoned, and I had no wish to approach it too closely.

Although wide enough for small cars or pony carts the road was very narrow, and as it climbed it wound along the side of a steep gorge, twisting and turning tortuously, at times going through deep cuttings. There was plenty of evidence that mule traffic had been heavy, but there was no sign of either troops or of human habitation. Approaching the summit I moved with care, for that seemed a likely place for a road-block, but I reached the saddle and there was nothing but silence all about; an eerie menacing silence as if something evil lurked in the gloom beyond the narrow circle of my vision. High banks of a steep cutting hemmed me in, and I had to go on for some distance before the side could be scaled.

From the roadside a level area of grass and bracken stretched to a hill on which small trees were growing, and beyond that lay China and my way to freedom. It looked as if my worst troubles would soon be over, but Hong Kong was not going to let me go so easily. The grass was almost waist high, and I had gone only a few paces when thorns tore deep scratches up my legs. But were those hard stiff trailers the usual flexible stems of thorn bush? They were not. Those were the vicious coils of barbed-wire entanglements, and the whole field of wire was buried in grass. The coils had been laid densely and with purposeful efficiency and, as the wire was galvanised and still in perfect order, I presumed that it had been laid by British troops.

No matter who was responsible for it being there it formed a difficult hazard, and my progress was slow and painful. So much so that I was afraid that daylight would find me a helpless target in the open, and being unable to gain any idea of the extent of this trap I decided to return to the road before it was too late. It was decidedly unpleasant to feel that whatever happened it was impossible to take any avoiding action. I could not even lie down, so my nerves were very much on edge by the time the road was regained. Half a mile on the Shataokok side of the ridge a small torrent rushed headlong down the mountain-side, and, making my way to that, I went over the edge of the road and slipped and slithered down to a secluded resting-place. The side of the gorge was very steep, and I had to wedge myself in among some large boulders, which looked as if they themselves might take to flight at any moment.

There was no comfort to be had, and once more I was glad when daylight diffused the eastern sky. Cold greys gave place to warmly glowing hues, until, in a rising crescendo of colour, there unfolded before me a most glorious masterpiece. The whole canopy of sky, flecked and streaked with cirrus clouds and level bars of haze, glowed and pulsed with a flood of light that mirrored and magnified on the glassy surface of Mirs Bay. Nature, in a mood of passionate inspiration, poured colours on the sky until it held a miracle of composition, overpowering in its prodigality. There indeed was inspiration for a Turner.

I watched spell-bound until the rising sun itself dispelled that marvel of its own creation, and then began to contemplate anew the problems immediately confronting me. The torrent tumbled steeply to a considerable stream which flowed along the bed of the gorge, and though the coast was invisible from my position, I knew that stream entered the sea at Shataokok. On the other side of the gorge a pathway followed the stream, and, while I watched, some Chinese came into view, carrying to the village their baskets and bundles of produce. Down near the stream, on my side, there was a patch of level ground with trees and bushes that would afford good cover, so I climbed down there, deciding to use the track to travel on after dark.

Not far from the confluence of the streams there was a perfect lair with nice soft grass on which to lie, but sleep had never been farther from me, and, after resting for some time, I cleared the stones from a pool and had a lazy, if not luxurious, bath. My clothes were almost dry, and in that warm sheltered place a sense of well-being came to me, though heaven knows there was little enough to give me any sense of comfort.

There were fat prawns in the stream, but in spite of every trick to snare them they always escaped from the most impossible situations, and at last I tired of the fruitless sport and returned to my soft couch. It was a delightful place, with many wild flowers in bloom, while birds and beautiful butterflies were my constant companions. There were prawns and small trout in the small stream, while in the larger one there were many fresh-water snails. Unfortunately those were beyond my sphere of movement, for that area was in full view of people walking on the track.

During one of my tours I saw some ripe pandanus fruit, most of them completely spoiled by birds or animals, but one was of such a rich ripeness that I determined to gather it. The fruit was high up, in sight from only a short section of the track, so as soon as a group of people had passed I sprang up the palm, secured the prize and successfully made off with it. From a distance it looked exactly like a four-pound pineapple, but closer inspection showed the core of the fruit to be surrounded by an outer casing of roughly hexagonal knobs, some three-quarters of an inch in diameter and about one and a half inches long. Those knobs felt as hard as wood and made a stout protective covering, but when two or three had been broken off, the others followed more easily. All that was left was a round kernel about the size of a cricket ball, of the texture of a potato. There was no flavour in it at all, but as it appeared to be quite innocuous I ate and hoped for the best.

An entry in my diary, written that afternoon, reads: “Am feeling rather weak; a good sleep would make a lot of difference. With any luck this should be the last of my most anxious nights, though do not know how far the ‘Nips’ hold.”

During the early afternoon huge billowing masses of cloud were piling up around the mountains, and thunder was rolling and muttering incessantly. The storm moved northward inside the coastal range and then it rolled out over Mirs Bay before turning inland again up the valley in which lay my pleasant little retreat.

It was a most awe-inspiring spectacle, tier upon tier of huge cumulus cloud rising to a tremendous height, intense indigo running into sulphurous high-lights, lightning streaming in all directions and stabbing viciously at the earth. After moving very slowly all afternoon the storm then came on at a great pace, and the cloud was swiftly overhead. Lightning struck at both sides of the narrow gorge, which was filled at once with a terrific throbbing roar, as burst after burst of thunder echoed and re-echoed between the steep mountain-sides. In a moment a deluge of rain came down, and for more than an hour that disturbance continued at its full power, after which the thunder lessened and gradually muttered away inland. Alas! for my brief comfort. Everything was completely saturated again, and my only wish was that darkness would come quickly.

After the storm had gone there was little traffic on the track, and by the time daylight had completely faded it had ceased altogether. The stream had been greatly swollen by the afternoon storm, so while there was still a little light left I made my way to the other side, climbed to the track and set off on another night’s adventures. That was the ninth since my departure from camp.

Soon the gorge was dark as in the uttermost pit. The track was very rough, it was washed out at innumerable places, and as there were vertical drops over the side I had again to feel for every foothold. It was very slow going until the valley opened out a little, when the track became much better. The lights of Shataokok came into view, and I pursued my way, very much on the alert.

Houses appeared on both sides of the path, and after warily passing several of them I came to a full stop when a sentry flashed his torch, perhaps fifty yards ahead of me. The way was too narrow and the fences too unknown to risk an encounter there, so retreating hurriedly I searched for a way down to the paddy. There were thick hedges and barbed wire along the sides of the fields, and it was some time before I could find a path leading from the road. Where it passed through the hedge it had been very effectively wired up, but the track was obviously one that had been extensively used, so reckoning that that would be as good as any other I worked my way under the wire. It was soon evident that Shataokok was a heavily guarded place for, along the road which I had left, sentries were stationed at intervals of little more than fifty yards. They continually flashed their torches across the flooded paddy, and I made a wide detour, for the lights shining on the glassy water made objects stand out in black silhouette.

Frequent delays were caused by rolls of concertina wire laid across the paddy, wire which had to be crawled through or under. I ploughed along through mud and water for an hour, and then a solid mass of buildings stretched right across my line of advance. Hoping to find a road that would take me through I advanced cautiously, but when one did eventually open up, instead of taking me to safety it brought me to a scene of uproar. Torches were flashing, lanterns hurrying about, orders were being shouted, and much commotion and unusual activity was afoot. That was very disappointing, for it meant that all the guards would be roused to the alert, and it would be foolish to a degree to try to pass through those streets.

The only way open was through the paddy on my right, so, although that meant going south instead of north, I had no option. For some distance I kept walking parallel to the buildings, and then veered away to gauge the width of the paddy and try to find out what lay beyond. Much sooner than I expected the ground suddenly fell in a vertical drop to a river below. There was no safe way down that cliff, and I sheered off to follow the flooded fields. These were narrowing rapidly, and rapidly too was my strength failing. Soon I could go no farther, and I sank down in the mud to rest and to try to decide on a course of action.

There seemed to be no way out of this impasse, and I was feeling very exhausted and low spirited. Suddenly it dawned upon me that there were no longer any buildings near. On the side where they had been there was only a bank about eight feet high. That proved to be a forbidding obstacle in the dark, for it was covered with a dense growth of thorn bush. Vicious spikes and barbs tore at my flesh as I pushed through to the top of the bank, but there, much to my surprise, I found myself standing on firm sand. There at last was the coast, and after crossing a hundred yards of dunes I saw surf breaking on shore. Again the sea was to befriend me.

Lieutenant-Commander Ralph Burton Goodwin OBE, RNZNVR.

Japanese troops march on to Hong Kong Island, December 1941. (Historic Military Press)

A clip from a news reel showing Japanese troops in action during the fighting for Hong Kong. (Critical Past)

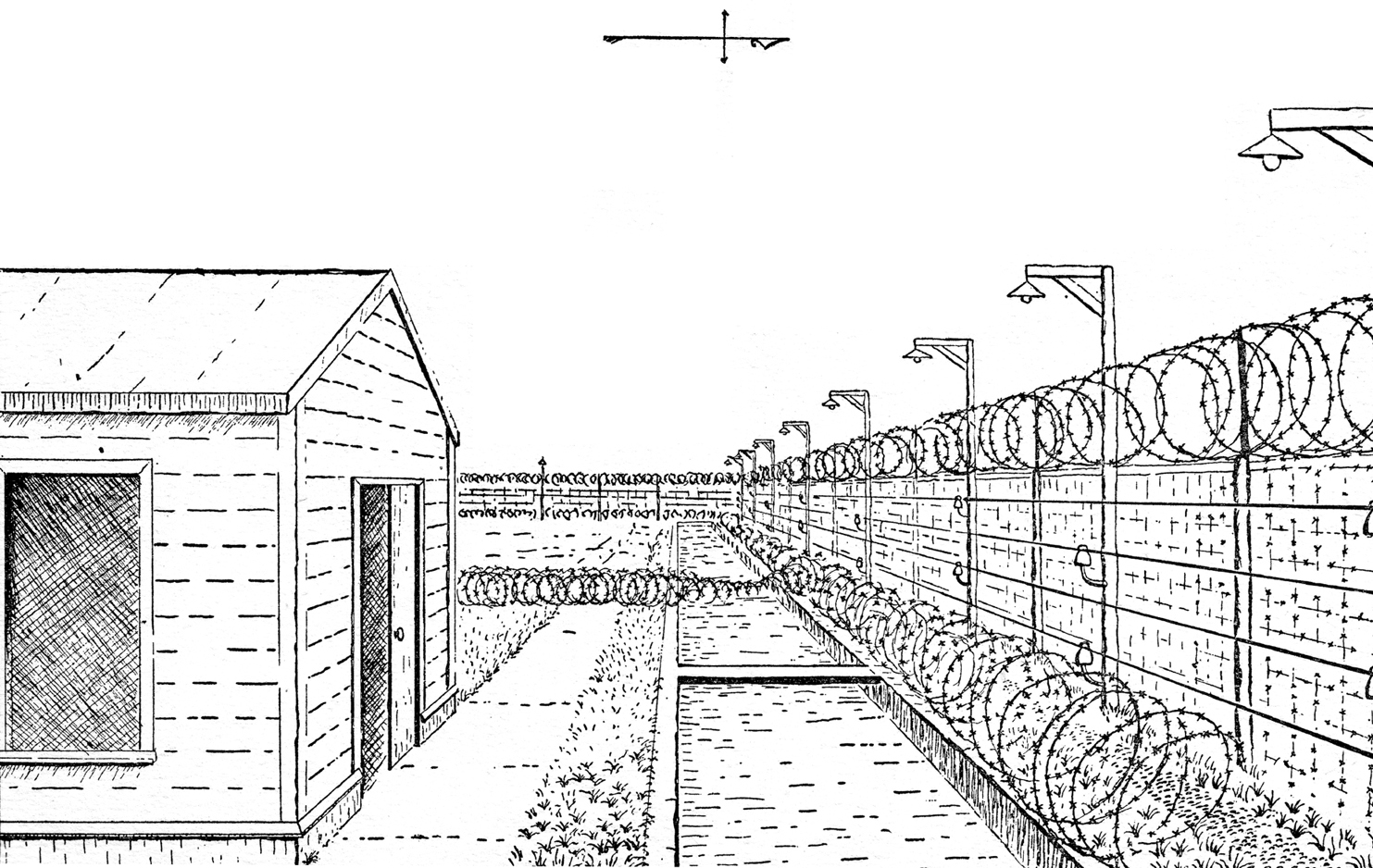

A plan drawing of Shamsuipo Camp.

Another clip from a wartime Japanese news reel, this time showing Allied naval personnel pictured in the immediate aftermath of their capture at the dockyard in Hong Kong. (Critical Past)

From film footage, this image depicts victorious Japanese troops posing for the camera after the fall of Hong Kong. (Critical Past)

A drawing depicting the north-west corner of Shamsuipo Camp.

Taken from a news reel, this picture shows Japanese troops awaiting an inspection having participated in a victory parade down Hong Kong’s Queen Street. (Critical Past)

Commander Peter MacRitchie with liberated Canadian prisoners of war at Shamsuipo Camp, Hong Kong, in September 1945. (Library and Archives Canada; MIKAN 3617924)

Major General Umekichi signing the Japanese surrender of Hong Kong on 16 September 1945. Rear Admiral Cecil Harcourt (C-in-C Hong Kong) signed the document in the presence Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser (C-in-C British Pacific Fleet).

Colonel Tokunaga under guard having been arrested as a war criminal in Hong Kong.

The memorial statue in Hong Kong Park which commemorates the defenders of Hong Kong in 1941.