CHAPTER 1

A STRANGER

Do the rivers in France smell like the Currituck?

Pam Lowder drew a deep breath and lifted her eyes from her speller to the blue-gray waters of Currituck Sound. A breeze had wandered in the open window, carrying the sweet scent of bayberries from across the marsh. I love the Currituck in fall, Pam thought. The air’s even more full of smells than in spring.

The breeze barely stirred the closeness of the classroom, and she couldn’t suppress a yawn. Miss Merrell’s spelling lesson droned in Pam’s ear until it mingled with the buzz of dirt daubers nesting on the windowsill outside.

Pam hated spelling. Why couldn’t they study something interesting, like geography? She wanted to learn the names of the rivers in France, so she could write Papa and ask him if they did smell like the Currituck.

Pam pulled her eyes back inside, to the rows of desks that kept the children of Currituck captive for five months of the year. If Mama weren’t so bent on Pam finishing school, she could be out on the sound right now in her skiff, fishing for white perch, or better yet, in her pigeon loft at home, tending to the squeakers that had hatched day before yesterday.

Miss Merrell was calling on the students in the sixth speller to recite. “Alice,” said Miss Merrell in her crispest spelling-word tone. “Spell mediocre.”

Alice Bagley stood up and recited without a moment’s hesitation.

“Thank you, Alice. That’s correct.”

“Show-off,” Pam whispered under her breath, though she knew she was being unfair. It wasn’t Alice’s fault if she always had the right answers in class. It was just that Alice was so sure of herself. But why shouldn’t she be? She was one of the smartest girls in the school and the most popular. Her father, as the postmaster, was the most influential person in Currituck, aside from the sheriff. He also owned the only drugstore in town and had been nice enough to give Mama a job when Papa was drafted last year.

Miss Merrell had started calling on the fifth spellers, those one book ahead of Pam. Sam Lewis. Fannie Rodgers. Louisa White.

Pam knew it would soon be her turn. She tried to study the words in her speller, but her thoughts kept slipping out the window, to the robin’s egg sky and the shining Currituck Sound, and to Papa’s last letter from … from “somewhere in France.” That’s all Papa was allowed to tell her and Mama about the location of his regiment in Europe. Papa was a doughboy in the American Expeditionary Force, which meant he was an American soldier helping the Allies in the war that seemed to have caught up the whole world.

Papa had been gone for many months, but he had only shipped overseas a few months ago. The rest of the time he had been training at Fort Monmouth in New Jersey, one of those tiny states up north. Last winter his letters from camp almost shivered with cold. Having lived in North Carolina all his life, he couldn’t get used to the bitter cold of New Jersey.

So far he had written only once from France. Pam pulled Papa’s letter from her dress pocket and reread (for the hundredth time) her favorite part:

The countryside is beautiful here, rich green meadows rolling up to cliffs that drop into the sea. The villages scattered along the coast look just like Currituck. Some of the villagers even keep homing pigeons, though nary a one is as handsome and strong as the Lowder pigeons.

Pam could see Papa winking at her as he wrote that. It was a secret joke between them that other pigeon keepers could brag louder, but none could raise better pigeons than she and Papa did. Maybe it was because they did it for pure enjoyment, not to race them as most of the locals did and, heaven forbid, not to fill somebody’s dinner table.

“Pam Lowder.”

Pam’s mind lurched away from her pigeons back to the classroom. Forty faces were staring at her, including Miss Merrell’s angry one. “You won’t find the word spelled for you in the sky outside the window.”

Pam knew her expression was as blank as the tablet in front of her. Which word had Miss Merrell called for her to spell? The boys across the aisle from her were starting to snicker.

“We’re waiting,” said Miss Merrell.

Pam made herself stand. Her mind raced. Which word? Which word?

“Locust.” A whisper from somewhere behind her. “Spell locust.”

Was it Nina? Best friends were for moments like these, weren’t they? Pam started to spell, hesitantly at first.

“L-O-C …” She stopped to think. Was it o next? Or u?

Titters drifted across the aisle. Pam shot the boys a dirty look and continued. “U-S …”

She paused again. There were snickers behind her now. Miss Merrell was glaring at her. They think I can’t finish the word, Pam thought.

“T,” she said loudly, to convince everyone she had been sure of the word all along.

The classroom burst into laughter. Pam felt her face flame.

“I suppose this is your idea of a joke, Pam.” Miss Merrell’s voice had taken on the icy tone she reserved for spitball throwers and other transgressors of schoolhouse law. “I would never have expected such behavior from you.”

“Ma’am?” Pam was perplexed. “What behavior?”

“Don’t act innocent with me, young lady. I called out encyclopedia. You spelled locust. Purposefully answering my questions incorrectly may get laughs from your classmates, but it also gets you thirty minutes in the corner after school. Standing on one leg. Now, let’s try to get on with our lesson.” With a hand on each hip, she turned to the other side of the room. “Linwood, spell encyclopedia.”

Pam knew the matter was closed. She sank into her seat and tried to hide behind Nancy Carlton’s head. Which wasn’t easy, considering Pam was the tallest—and oldest—student in fourth grade.

A black funk settled over her like a swarm of flies. How many times had Mama warned her about daydreaming in class?

“You can’t afford to miss any more lessons than what you do when you stay out to help me on the farm,” Mama had said only last week. “Make Papa proud of all you’ve learned when he gets home from the war.”

Make Papa proud of you. The words rang through her head. And look what she’d gone and done. Made a fool of herself in front of the whole school and gotten herself in trouble to boot. Papa surely wouldn’t be proud of her now.

Who had played such a dirty trick on her?

Pam stole a glance behind her. Her eyes met Nina’s, and Nina jerked her head to the left and back one more row, toward Henry Bagley, Alice’s bratty younger brother. Henry, legs in the aisle, hands behind his neck, was grinning like a possum. When he saw Pam looking at him, he mouthed “locust” and doubled over with silent laughter.

Henry! Who else?

He made it a point to get Pam’s goat every chance he got. And he didn’t even have to work at it. Henry just being Henry was enough. The worst thing was, Pam had to put up with him because Mama worked for his father. Mama agreed that Henry was a pain, but she called him “an affliction” Pam would have to bear.

Pam tilted her head and smiled sweetly back at Henry, but she filled her eyes with venom.

He stuck out his tongue.

When Miss Merrell finally released Pam, the school yard had cleared out. Pam was glad she didn’t have to see the other kids. Then she spotted loyal Nina sitting under the chinaberry tree, eating a biscuit from her tin lunch-pail. Nina hopped to her feet as Pam dragged down the schoolhouse steps.

“You were in there a long time.”

“Yeah.” Pam knew Nina wanted details. After all, they usually told each other everything. But Pam couldn’t this time. She just couldn’t.

“Want some of my collard biscuit?” Nina asked, as the girls climbed over the stile in the school yard fence.

“No, thanks. I’m not hungry.”

“Well, what did she say to you?”

“I don’t want to talk about it,” said Pam.

“Why? Did you get a whipping?”

“No!” said Pam adamantly. A sigh escaped from the depths of her soul. “She stood me in the corner and lectured me on behaving in a fit manner for a soldier’s daughter. It made me feel awful. She said I was letting Papa down by not applying myself and by being a smart aleck.”

“Didn’t you tell her what Henry did?”

“No use. I’d still be in trouble for not paying attention. I might as well admit it, when it comes to school, I’m a dolt.”

“No, you’re not.”

Pam forced a smile. “Thanks, Nina, but it’s true. I’m two grades behind Alice Bagley. And she’s twelve, same as me.”

“It’s not your fault. You have to stay out of school so much to help your parents on the farm. You come to school a lot more than the other farm kids. Look at your neighbors, Buell and Mattie Suggs. They can’t even read.”

“That’s different. They’re tenant farmers. Their ma and pa think school’s a waste of time because those kids can’t hope for anything more than farming someone else’s land. Mattie acts like she don’t care, but I know she wishes she could read.”

The girls had reached Nina’s front gate. She lived next to the courthouse, a block down Main Street from the school. Nina’s father, Judge Patterson, was the only lawyer in Currituck County. Since cases in sleepy little Currituck were few, he worked mostly in Elizabeth City, forty miles across the Albemarle Sound.

“You want to come in for a while?” Nina asked.

Pam shook her head. “Can’t. I’m already late meeting Mama at the store. Maybe tomorrow.”

Pam continued down Main Street, the only real street in town, unless you counted the rutted lane that ran by the lumber mill and the steamer dock and stopped dead at the river. The few businesses in town—the general store and the dry goods, the drugstore, the bank, Purdy’s Grain and Seed—were scattered along Main. The entire street was barely half a mile long, but the drugstore was way at the other end.

Pam picked up her pace, hoping to reach the drugstore before she saw anyone she would have to talk to. She passed Doc Weston’s house with his tiny office in back, then the Farm Bureau. At the general store, Pam noticed two new posters in the window. One poster announced the community patriotic meeting for the week, a public “singing” on Saturday night in the opera house above the store.

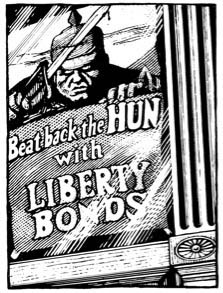

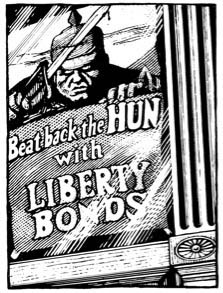

The second poster, Pam knew, was just meant to stir up people to buy government bonds to pay for the war. Still, it made her shudder. A devilish German soldier clutched a dagger dripping with blood. “Beat Back the Hun with Liberty Bonds,” the poster proclaimed. An image flashed into her head: Papa in battle, crawling on his belly through no-man’s-land, while the Hun with his dagger waited over the next rise. She pushed the image from her mind. I won’t think about that, she told herself. Papa knows how to defend himself against the Germans. Mama said so.

She couldn’t help worrying about him, though. If only the Allies would hurry up and win the war so Papa could come home. She had read in the newspaper only last week that the Germans were retreating in France. Folks were saying it was the beginning of the end, though Mama told Pam not to get her hopes up. Wars took a lot longer to finish than they did to get started, she said.

Pam sighed. If only Papa could come home, everything would be back to normal again. But the Hun on the poster gloated at her. Your papa won’t come home if I have anything to do with it, it seemed to say. Anger and resentment surged through her. The Germans were barbarians! They must be—dragging the world into war and taking girls’ fathers away from them!

Pam felt gloomier than ever. She was in no mood to see Alice and her friends Louisa White and Fannie Rodgers strolling down the sidewalk toward her. Pam could hear their laughter even from where she stood. Alice had gotten her hair bobbed in Norfolk last week, and she was wearing a new white dress from the Sears-Roebuck catalogue. Pam’s cotton dress and scuffed brogans, which usually suited her fine, made her feel more awkward than ever next to stylish Alice.

Alice and her friends walked abreast, and there was no way Pam could avoid them. Rudeness was a sin in Currituck; if Alice spoke to her, she would have to speak back. Alice was friendly to Pam at the drugstore, but at school she seldom ventured out of her circle of friends. Maybe she would be too absorbed in conversation to notice Pam.

No such luck. “Hey, Pam,” said Alice. Louisa and Fannie echoed Alice’s greeting but continued to whisper and giggle.

Pam was sure they were talking about her, laughing at her for making a fool of herself at school. “Hey,” she muttered. She lifted a hand in greeting but strode past without saying anything more.

She found Mama sorting mail in the post office, which was just a back room of the drugstore. “Anything from Papa?” Pam asked.

Mama shook her head. “Nothing.” Her lips were set in a line.

“Shouldn’t we have heard something from him? Just a line or two to let us know how he is?” Pam’s stomach churned. Was Mama worried about Papa too?

“I’m sure we’ll hear directly, sugar. Papa don’t have much chance to get mail out to us, is all.” She touched Pam’s cheek and brushed aside a wisp of hair that had escaped from Pam’s braids. “Why the long face?”

Pam told Mama what had happened at school. “I’m not going back,” she insisted. “I’ll be more use to you at home than I am in that schoolhouse. I’d have the house cleaned and supper cooked before you got home at night. Then you could sit in your rocker and rest up from working all day.”

“I’ll not have my daughter keeping my house while I loll around with my feet propped up.”

“Mattie does all the housekeeping at her house,” said Pam.

“So she does, poor li’l thing.” Mama clucked. “Fond as I am of Iva Suggs, I think she’s done wrong by those younguns keeping ’em out of school. Just ’cause she and Ralph never had a day’s schooling in their lives is no reason to deny an education to their younguns.

“Times ain’t like they was when Iva and me was growing up. This war is changing everything, even in Currituck. Young folks need an education to get on in life now. Papa and I have hopes for you, Pam, to go on to high school and make something of yourself.”

“High school?” This was a new notion to Pam, and she wasn’t sure she liked it. She’d never thought much beyond the boundaries of the one-room schoolhouse and Currituck County. “Then I’d have to board in Norfolk or Elizabeth City. I’d have to leave you and Papa and Currituck.”

“I’m not saying you have to. We only want you to have a choice. And the way to have a choice is to stay in school and do your best.”

“I do try, Mama. I try to stuff my head full of all that book learning, but it seems to slip away as fast as I stuff it in. I have to work twice as hard as the other kids just to keep up.”

“Nothing worthwhile ever comes easy,” said Mama.

“Nothing comes easy to me.”

“That’s not true. Animals come easy to you. Why, it’s almost like magic the way you can tame a coon as if it was a kitten, and have wild jays flying down and sitting on your shoulder. And look what you done with your pigeons. Who else has a loft of pigeons that will home at night in the worst of weather? You’ve got a gift, Pam. You do.”

“What use is a gift like that?”

“Hold on till I finish this mail, sugar, and I’ll tell you how much your gift is worth.” She stuck the last few letters in boxes and sat down beside Pam. “A man showed up in town today, a stranger. He was dressed peculiar—clear he wasn’t from around here. He drove his motor truck up and down the street, like he was looking for something, and then he finally stopped in front of the general store and went in. Miz Gracie Langley happened to be in here getting some headache powders, and she nearly had a fit to know what his business was. She hustled to the general store straightaway and come back so flustered she could hardly talk. She kept sputtering about his accent. Flat out begged Mr. Bagley to send a telegram to the CPI right away to report the man.”

Pam was alarmed. “The CPI—isn’t that the government agency that hunts down …” Her voice trailed into the air. It was too scary to think about the answer to her question.

“Yes. Spies,” Mama finished for her. “Miz Gracie is convinced the man’s a German spy.”