CHAPTER 5

A PROWLER

Pam took a roundabout route through town, running all the way. She didn’t feel safe until she reached the drugstore and there was still no sign of Arminger.

She collapsed on the front steps, gasping for breath. It was only then she remembered her disgrace at school and Henry’s threat to have Mama fired.

She picked herself up and made herself go into the store. Mama was wiping down the glass doors of the big oak cabinet where Mr. Bagley displayed his wares. On the top shelf were the ladies’ toiletries: jars of cold cream, hairbrushes and combs, nail files, bath powder, fans. Under that were shaving mugs for the men and boxes of cigars and pipe tobacco, and the bottom shelf held soap flakes and toothpaste. On the other side of the cabinet were the tonics and cure-alls: Rexall Olive Oil Emulsion, Rexall Liver Salts, Gold Medal Ephedrine Nasal Jelly, Dr. Miles’ Laxative Cold Cure, Karnac Stomachic Tonic and System Regulator.

At least Mama still has her job, thought Pam with relief. Mr. Bagley was nowhere in sight.

“Has Henry been here?” Pam asked Mama.

“He ran in a while ago, but skedaddled when he found out his pa had gone out to Slidell. We sold clean out of all those bottles of old Mr. Tripp’s nerve tonic, and Mr. Bagley went to fetch some more,” Mama said. “What you two doing out of school?”

Pam poured the whole story out to Mama, including the episode with Mr. Arminger. She left out only the part about Henry’s threat. There was no use worrying Mama since Henry hadn’t carried through yet. Mama listened without saying much, but Pam could tell she was none too pleased with any of it. When Pam finished, Mama was silent for a minute. “Well, I hope you’re pure ashamed of yourself.”

Pam hung her head. “Yes, ma’am. Terrible.”

“That’s punishment enough then. ’Cept maybe you’re due to copy down some Bible verses ’bout patience and not being provoked to wrath. You got to learn to put up with Henry, Pam. Ain’t no two ways about it.”

Pam knew Mama was right. But she still wondered how Henry could have known Arminger wanted to buy her pigeons. She asked Mama.

“Why, Henry was here the whole time I was talking with Mr. Arminger, the first time he came in asking after your pigeons. Henry run over from the schoolhouse during recess. He was up at the soda fountain, begging his pa for Coca-Cola, but I s’pose he could’ve heard most of what was said.”

Mama stopped her cleaning and looked earnestly at Pam. “Listen, honey. About Mr. Arminger. I’m afraid I scared you the other evening. Ain’t no cause to fret if he speaks to you first. Just don’t be over-friendly till we know him better, hear?”

Pam nodded. “What about all the talk about him?”

Mama chuckled. “Funny how quick that German spy business settled down once he commenced to spending good American dollars. Miz Langley flounced in here this morning singing a total opposite tune. Said Mr. Arminger gave an in-spirin’ address at the community loyalty meeting last night and a heap of money to her Red Cross goose sale. Now she’s plumb tickled he’s settling down in Currituck.”

“He’s staying then?”

“Already bought him up a piece of land in the woods upcreek from us,” Mama said. “You recollect old Sanders the hermit? Your papa used to fish and hunt with him years ago. Papa was pretty much the only person Sanders would cotton to, and it was Papa who found him dead in his cabin and buried him, remember?”

“Yes, ma’am, I do. Papa took me out to his cabin a few times. Mr. Sanders kept a passel of animals in the house. His coon ate out of my hand, but wouldn’t get near Papa. Mr. Sanders said he could tell I had a rare way with animals.”

Mama nodded, remembering. “Seems Mr. Arminger is setting up housekeeping in Sanders’ old cabin. The way I hear it, he’s a fisherman from New England, come south with his sons to take up herring fishing. And he’s looking to raise some birds, he says, leghorn chickens maybe. Maybe pigeons.”

At that moment suspicion flared in the pit of Pam’s stomach. Arminger’s story didn’t add up. “He didn’t appear to know a thing about fishing the other night. Seemed to know more about animals than anything else.”

“He’s been fishing up north, sugar. I reckon it’s a different business up there.”

“Don’t it seem peculiar he was buying grain instead of fishing gear?”

“Likely he already has his gear.”

“But, Mama, all that grain—like he already had him a mess of pigeons.”

Mama heaved an impatient sigh. “Pam, leave it be. The man prob’ly up and bought birds from someone else. Yours ain’t the only pigeons in the county.”

Pam fell silent. She was deeply stung. She hadn’t realized how much Arminger’s admiration had meant to her. Now he appeared to have found other pigeons that suited him. A passel of ’em.

The wind was blowing steady out of the northeast by the time Pam and Mama got home. Gray clouds hung low in the sky, and the creek was chopping straight up and down. It was prime fishing weather. Bluefish would be running; spotted sea trout would be up the river.

“Wouldn’t Papa be rarin’ to get out on the water?” said Pam aloud. She was on her way to the toolshed where she stored her pigeons’ food. A voice inside her added, If he was here. Pam’s throat swelled and ached. Nothing was the same with Papa gone. Nothing.

Then Bosporus came bounding out of nowhere, barking furiously. The wind was bristling his fur and making the hair on his neck stand straight up. He jumped up on Pam and seemed to dance for a minute on his hind legs. Pam laughed. He reminded her of a clown she’d seen once on a circus poster.

Pam stroked his muzzle affectionately. “You’re in high spirits today. Can you feel the storm coming on?” Bosporus whined deep in his throat and loped to the toolshed. He stood outside the door whimpering.

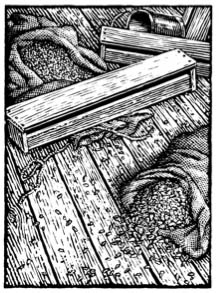

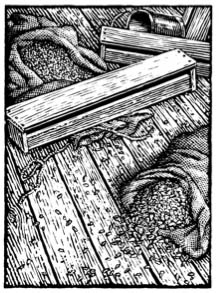

“You are some anxious to get them pigeons fed, ain’t ya, boy?” When she opened the shed door, though, she realized it wasn’t high spirits that had Bosporus acting funny. Sacks of barley and oats lay askew, spilling their contents onto the floor. Maple peas and sunflower seeds were scattered everywhere. Some old feeding troughs had been knocked off a shelf. An empty paper sack, blown by the wind from the open window, scratched across the plank floor.

“So. This is what you were trying to tell me, Bos,” Pam said with dismay. “Someone’s been in here. Escaped through the window, looks like.” She pushed down the sash with a bang. “Who was it, Bos? Someone you—” But she cut herself off. Something was moving down by the barn!

She raced outside. Daylight was fading fast. The bullfrogs from the creek were starting to growl, the crickets to sing. Had she really seen anything? Maybe it was just her imagination.

No, there it was again, a shadow flitting into the barn!

Her senses alert, Pam crept into the dimness of the barn. She held her breath, waiting, waiting to hear something, anything, out of the ordinary. But there was nothing. Only Lula and Daisy stamping in their stalls. Pyrenees lowing for milk. A mouse scuttling up in the hayloft. She searched the empty stalls, the corner behind the plow and the old wagon, the tack room where Papa kept his crab pots and fishing nets and his hip boots. Nothing.

Bosporus was lying obediently just outside the barn waiting for Pam. “I could’ve sworn I saw someone,” she told him as she fastened the latch on the barn door. He whined and thumped his tail on the ground.

That was when Pam noticed the cigarette butt in the dirt. “How did that get here?” She bent to pick it up, but suddenly froze. Her pigeons were squawking!

Padding as quietly as she could through the growing darkness, she hurried to the loft. The wind had picked up, and it was growing cold. All she could see were shapes and shadows, until she was nearly on top of the loft. Then what she saw sent a shiver down her spine.

It was Arminger. With Caspian perched on his shoulder.