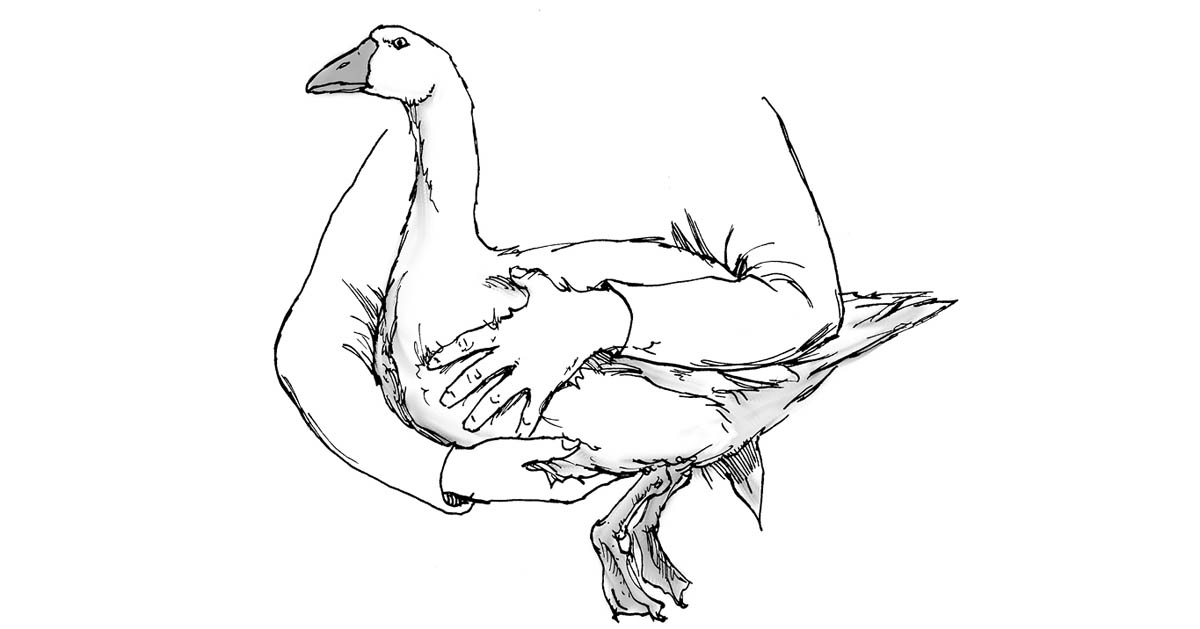

Angel wing. This is an unfortunate defect which prevents birds from being show quality.

Raising poultry for show can require different methods from what one might use to raise poultry for future production. Your goal is to produce birds, by showtime, that are not only healthy and clean but also excellent representatives of their breed and grown to an optimal size. You want these show birds to grow fast but remain in peak condition. In many cases, this will involve selecting different feeds and being careful about how confined and crowded your birds are. Take care to keep your birds growing at a proper rate and not to overdo it with treats and other items that might lead to future problems.

With many commercial meat birds, the true characteristics of the breed will appear only if you offer the proper feed that the genetic line is accustomed to. If you use homemade recipes for feed, you can run into serious issues with many lines of meat chickens, as I saw at a fair I judged.

Typically, in the area of the Midwest where I live, fairs require that all entrants get their chicks from the same hatchery on the same day, and all are wing-banded to ensure accuracy and integrity. Each exhibitor is then allowed to raise the birds as he or she sees fit, and on the day they are judged, the pen of three (as it usually is) is weighed and evaluated for health and growth rate.

In one such contest, with about 25 entries, the weights of the entries for three birds ranged from 9 pounds to more than 26 pounds. That variability may seem hard to believe, but after each exhibitor was questioned, it became increasingly understandable.

The pen of three that weighed only 9 pounds, while healthy looking, had been raised on a homemade food mix and on pasture. They were also not on continuous feed. The pen of three that weighed more than 26 pounds had had 24-hour-a-day access to feed and water, were kept in a small confined area, and had spent their short 8-week lives not moving more than 6 to 8 feet in any direction. Unfortunately, they couldn’t move at all anymore, with open sores on their feet and hocks. They had been ready to butcher 2 weeks earlier and were currently on a downward health spiral.

I always encourage young exhibitors to strive for the middle ground and consider the health and quality of life for the birds. Provide adequate food and proper care.

A good healthy start is crucial to a good finish at the show. For the first few days, a young bird’s system is getting established, so a proper feed ration is essential. If the birds arrive in the mail very stressed (stressed birds will be lethargic, droopy, and have a low, dull peep), start them out on a 50-50 mixture of hard-boiled egg and fine cornmeal. The egg yolk is particularly nutritious and will help get the chicks back on their feet. If all is well upon arrival, start out with a properly balanced food suitable for day-olds. Most feed stores offer a well-balanced poultry starter in the range of 23 percent protein.

It doesn’t hurt to start all species on a game-bird starter, which has a protein rating of 28 to 30 percent, and continue it for a few days. For waterfowl, it is particularly important to cut back on the protein within a few days (and definitely keep them on game-bird starter for no longer than 1 week). Waterfowl on too rich a diet will most assuredly develop angel wing. Turkeys, guineas, game birds, and small, frail bantams can be left on this high-protein feed for 8 to 16 weeks.

For most breeds of chickens and bantams, an average 23 percent protein starter feed should be fine; then as the season progresses, you can wean them down to 18 to 21 percent protein. If you do start chicks on game-bird starter, be sure to offer a lower protein feed after the first week or so. While it might seem like a good idea to keep chicks their entire lives on a game-bird starter, the long-term effect on the birds is harmful. Continuous high protein levels in adolescent birds can do some damage to the kidneys and slow the birds’ growth rate.

The switch to lower-protein feeds happens at different times for different poultry. For chickens, give 18 to 21 percent; for ducks and geese, around 15 percent; and for turkeys, 23 percent.

I start backing off the protein level on chickens at about 3 to 4 weeks, on average. There are a few frail types that can be kept on high protein for a longer time. It would be best to keep the frail ones at the 18 percent level until showtime.

Waterfowl are the most sensitive to very high levels of protein, starting at 21⁄2 to 3 weeks of age, when their previously small, undeveloped wings start to grow at a rapid pace and they begin to feather out with adult feathers. Prior to this time, they are covered with down. Feathers are mainly protein, so a high-protein feed will spur the growth of large feathers in the wing area that will cause a condition known as angel wing or airplane wing, in which the feathers outgrow the bone support underneath and the wings tend to flop outward. Though this is not painful for the bird, it will prevent you from successfully showing the bird at a fair or an exhibition.

For waterfowl, the key is to offer them plenty of fresh green feed when they begin to feather out, preferably by letting them graze on a lawn or specially planted pasture mix for poultry. They will balance out their diet properly between your prepared feed ration and the greens they acquire from the pasture. The alternative is for you to cut green goodies for them every day and deliver them. While this works, it is more labor intensive and not nearly as effective as when the birds can pick and choose what they want to eat. Geese in particular will daily increase the grass and green feed part of their diet as they get older.

When raising young males for showing, you will need to closely monitor their growth and maturity. As they reach sexual maturity, they can damage the feathers of both young pullets and other males in their desire to show dominance. Crested fowl, too, will require special care and maintenance. The crest always seems to be a target for other birds to damage.

Turkeys and guineas need a higher-protein feed for a longer period of time than do any of the other species of poultry. I would not cut the protein level down to 23 percent until they are at least 12 weeks of age. In nature, their wild counterparts have a diet very rich in insects, and the birds are genetically programmed to need the higher levels of protein.

When your future show winners are 3 to 4 weeks of age, it is crucial that you handle them properly. It is easy to be affectionate and cuddly with little fowl — whether chicks, poults, ducklings, or goslings — but once they start getting their feathers, the cuteness disappears and the handling tends to decrease. You must handle your birds frequently if you intend to show them, because the birds need to become familiar and comfortable with human contact if they are to develop the desirable show traits of being calm and relaxed.

Calm, relaxed birds that are used to human contact will always perform better. If you are a youth showing at a 4-H or FFA show, you will be judged on showmanship and how you handle your birds. A good juvenile-fair judge is often strongly impressed by a young exhibitor who has good handling skills and birds that appear relaxed in the owner’s hands. This sends a clear and distinct signal that the exhibitor has control and has truly done the project of raising the fowl.

Each type of fowl handles the show experience differently. Chickens and bantams are perhaps the easiest to show. Some varieties of bantams even appear to enjoy the experience and the extra attention they receive. Ducks generally deal well with shows but are far more comfortable when not confined in a cage. Geese simply tolerate the experience and can’t wait to get home to their water and pasture. Turkeys will most likely not look their finest at a show except in late fall, when males will strut their stuff if other males are present. Hens will usually cooperate but not enjoy the experience.

In showmanship classes for youth, judges will ask young exhibitors to remove their birds from the cage. When doing this, it is important to understand each bird’s individual adaptation to the show scene. First and foremost, always try to take the bird out of the cage head first and with as little struggle as possible. The more struggle, the less desirable the bird will look.

Reach into the cage and bring one hand down on top of the bird and with the other hand grasp the feet. With the hand on top covering the wings, and one on the feet, bring the bird out. The top hand should prevent the wings from flapping around.

How to hold a chicken. Support the feet and lower body to give the chicken a better feeling of security.

Ducks are another story. You must not pick them up by their feet, and their wings can be sturdy and might hurt a small exhibitor. It is best to grab the back and hang on to the wings. Then, with your hands under the body at the base of the feet to give support (not hanging on to the feet), bring the bird out of the cage.

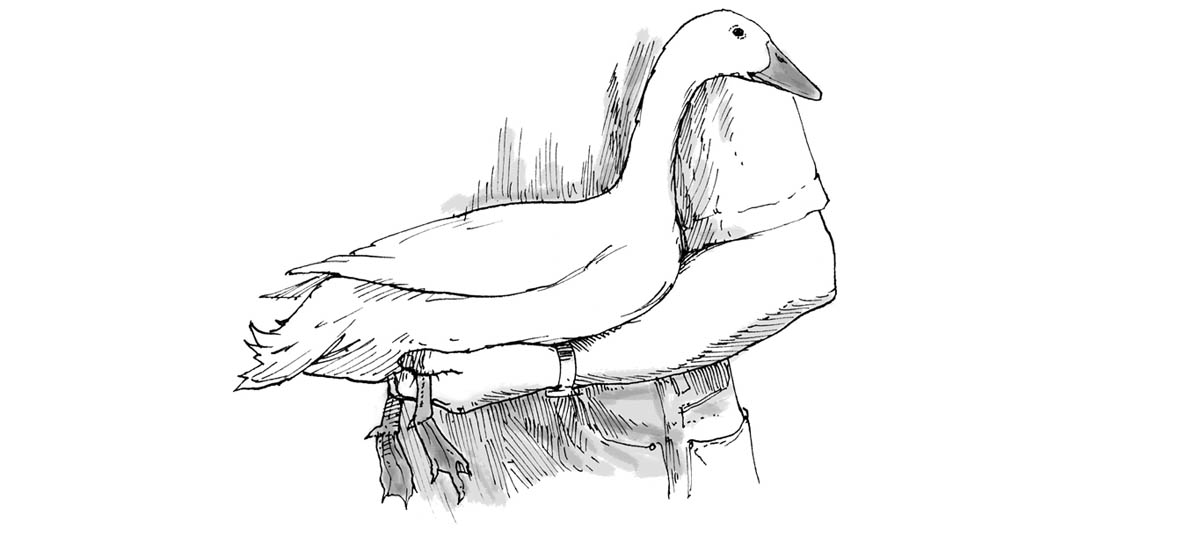

Geese are handled similarly, except the birds are so large that they will need a bit of care to make sure that their wings aren’t damaged on the way out of the cage and, once out, do not harm the exhibitor. A goose’s wings are very strong and the ends can be snapped if the exhibitor holds too tightly as the goose squirms. This is usually only a problem in geese less than 1 year old, which have more fragile bones.

How to hold a duck. Place your hand and arm under the body at the base of the feet to give support.

How to hold a goose. Hold the bird against your body with one hand, and hold the outside wing with the other hand.

Turkeys are a real challenge for small exhibitors; in fact, their size, particularly with commercial meat turkeys, makes them very difficult for most exhibitors. Commercial turkeys in most cases should probably not be picked up to be evaluated; you and the judge should examine the bird while it’s in the cage, checking the breast, legs, and thighs for defects. These birds can have challenging heart and respiratory issues (see box below), and a lot of handling in a hot summer show can be a life-ending experience for the birds.

Traditional heritage turkeys do not generally have the health problems of their commercial cousins, but they are more active and tend not to like the handling experience, trying to flap and squirm. Some judges will expect you to remove your heritage turkey from the cage, if nothing more than to check to see if you have any experience handling it. This can be a challenge with the bird’s large size, especially if the exhibitor is small. If you can, reach into the cage and grab the bird’s legs with one hand and cover the top of its body with your other arm to provide security to the bird and protection to yourself from the wings. It is not terribly hard to handle turkeys, and once they feel secure they will not flap. All of your advance preparation will help, but still, at the last minute the show experience can frighten them, and they may not react as expected.

How to hold a turkey. A firm hold on the wings and feet will prevent injury to both the bird and the exhibitor.

Modern commercial turkeys have been genetically changed to the point where their body mass is so great and out of proportion that they cannot handle being carried by their feet or held on their backs, as their mass will press against their lungs and they will struggle to breathe. They are also prone to weak, flabby hearts that can give out easily if placed under stress. As an even further complication, their bones are weak and break easily.

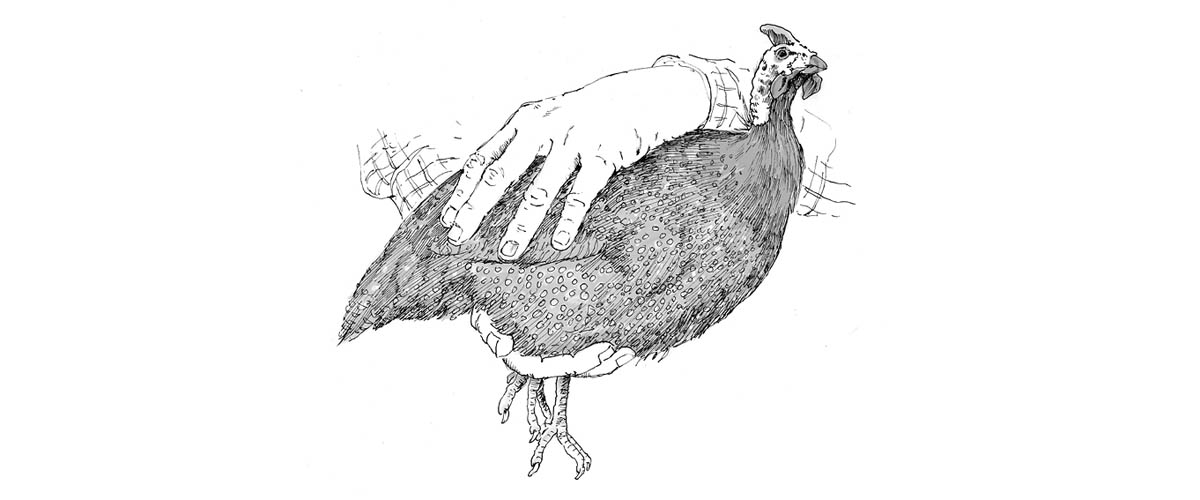

To handle guineas, you must use a great deal of patience and care when you reach into the cage. If you grab at the back to catch one, it will release its feathers and you will end up with a bare-backed bird. Instead, you must catch it by the feet and then carefully, without tugging or pulling, cup the top of the bird to make sure you do not cause it to release its feathers.

Guineas also have the unique trait of striking out at the person that has hold of them. They have long necks and sharp bills, and they can inflict serious damage if they get near the face and eyes. They will panic, as is their nature, so be prepared for that.

How to hold a guinea. Care must be taken to secure the legs and wings.

Game birds, such as Bobwhite quails and Chinese Ringneck pheasants, are a true challenge to show, and the exhibitor needs lots of hands-on experience with them to make sure the fair day is a positive experience. They will not respond well to being in cages, and in many cases you will need to put a cover on top of the cage to make sure they do not fly up and hurt their heads on the roof. It is their nature to try to escape, and they will do that frequently. For this bird, you will want to lock the cage so no one opens it up and you accidentally lose your project.

This is one case where you will have to spend considerable time with the birds to be able to handle them. Raising game birds for show is not for the person who wants an easy, maintenance-free project.

If you will be participating in youth shows, just picking up and carrying your birds around is not all that is needed: you must also be proactive and practice taking them in and out of a cage. I always recommend to young exhibitors that they frequently practice this as the birds are growing. Most fairs have their own cages, but you will do better if you have something similar of your own to practice with at home prior to the show. The easiest method is to acquire some wire cages, which you can purchase at many farm stores. Rabbit cages are excellent for this purpose.

Bantams are usually the easiest to train, followed by most breeds of chickens, then ducks. The least happy of the common show fowl will be the geese and turkeys. Guineas and game birds are far worse, and you have to take special considerations when showing fowl such as pheasants and quail. You will need to have a fairly secure cage with a top. Prepare to have a lock, and in some cases you will need to provide something to wrap around three sides to prevent fright and injury. Some shows even allow peafowl, and they need a large cage to allow the males to roost and maintain proper tail conformation.

It can be quite traumatic for a young bird to be thrust suddenly into a show cage with a wire bottom suspended above open air if it had been on a wood, concrete, or dirt floor for its entire life. Poultry have a natural fear of falling, so seeing the ground some distance underneath for the first time may cause a temporary paralysis or make them start flying frantically and uncontrollably. This can make for a very bad show experience. I do not deduct for this when I am judging, but I give the exhibitor tips on how to avoid the problem in the future. Many judges do deduct for this behavior, especially in a showmanship category.

When you first start training to caging, it is best (especially if the birds are used to being on the floor) to slip either some straw or a piece of cardboard into part of the cage so they can retreat to what is more familiar and gradually become accustomed to the new type of environment. As they adapt to this type of living situation, the fear will dissipate, and there will soon be no need for anything in the cage except the feed and water.

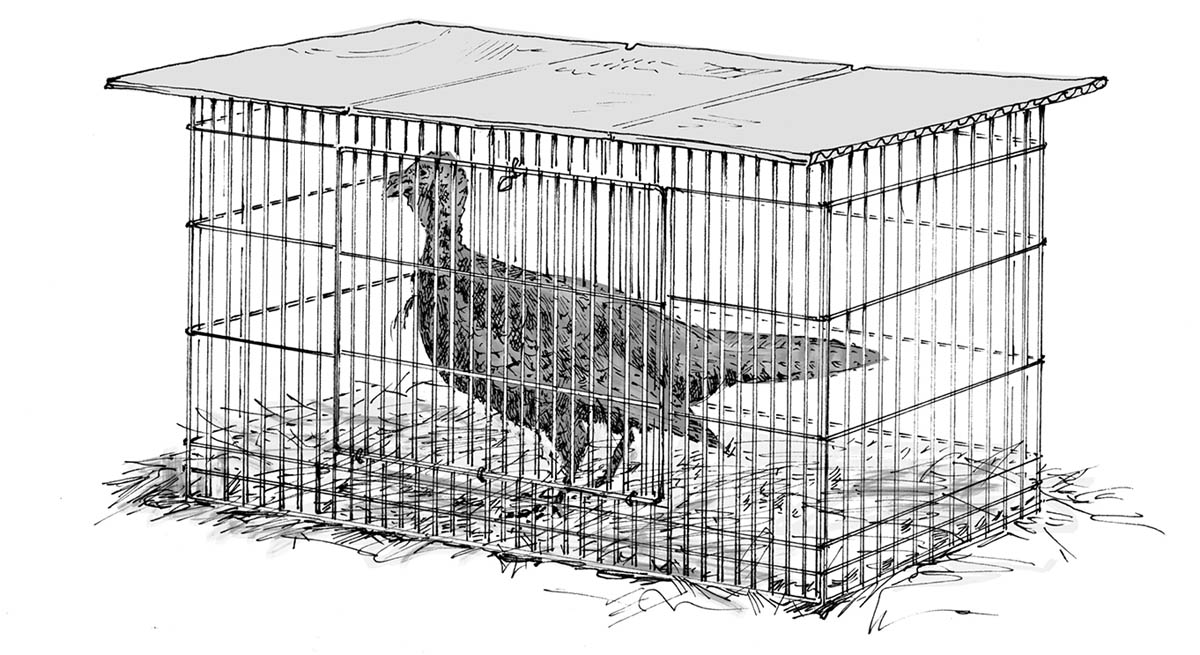

Geese and turkeys usually are shown in floor cages, so getting them used to the cage is more of a relaxation training to make sure the birds do not climb and flap around inside. To start training larger fowl, you may need to cover the top of the cage with a piece of cardboard or something similar that gives the bird a feeling of security. Contrary to fowls that are afraid of falling, the large birds are more afraid of what is above.

Pheasants and quail will constantly fly and crash against the top of the cage. In some cases they may kill themselves by beating their heads so many times they will first lose their feathers, then eventually either bleed to death or suffer severe brain damage from the experience. Beginners should avoid these birds until they have some experience under their belt. The key here is to spend time with the birds and familiarize them with their surroundings.

Getting a turkey used to a cage. Make sure to start cage training with the top of the cage covered.

When youths are showing any poultry, it’s a big plus if the judge sees that the bird is at ease in the exhibition cage. While it is easy to eventually cage-train most breeds of bantams, chickens, ducks, and even geese and turkeys, game birds and some guineas will never be at ease in a cage. If you are able to accomplish such a feat and make it look as though they are in total relaxation when in an exhibition cage, you will undoubtedly impress any judge with your showmanship skills.