Preface

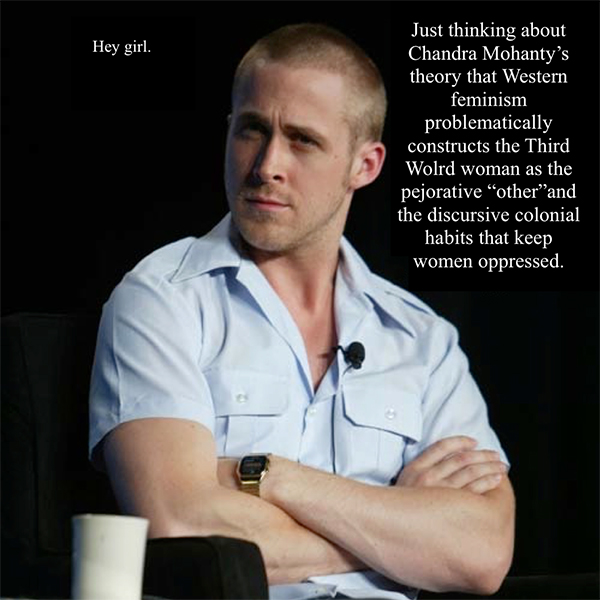

Few things capture the tenor of my bookish youth better than Feminist Ryan Gosling. This celebrated meme (first on Tumblr, later collected into a book), created by University of Wisconsin graduate student Danielle Henderson, features dashing photos of the Canadian actor captioned by insights from academic feminist theory. When Feminist Ryan Gosling, frocked in a light-blue, collared shirt, looked softly back through my computer screen one spring day in 2011 to say, “Hey Girl. Just thinking about Chandra Mohanty’s theory that Western feminism problematically constructs the Third World woman as the pejorative ‘other’ and the discursive colonial habits that keep women oppressed,” I saw nothing so much as myself in 1998. And, Reader, it is not because I look like Ryan Gosling.

The theory that animates this meme also animated my college days. Back then “theory” was the name for an identity: an idea of how to be, a way to live your life. We used the term also to refer to the idiom that expressed the identity—“theory” named a way of thinking and talking about language, power, and history, drawing on a canon of mostly European-educated scholars, philosophers, and psychoanalysts (or, as we called them all, theorists): the likes of Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, Julia Kristeva, and Jacques Lacan.

Both this idiom and this life plan gathered meaning from their use. Never mind what defined “theory” in any certain terms or what criteria distinguished a theorist from a mere philosopher or critic. What mattered to us was that mastering theory—being, as the common sobriquet identified us, “theory heads”—was a way of recognizing fellow pilgrims en route to the same promised land. Theory’s singular idiolect gave my friends and me, in our youth, a springboard for thinking about whatever was to come after youth. Theory offered us a way of understanding the world that, like so many youthful exuberances, was equal parts vital and ridiculous. Verbose abstractions were things out of which we built concrete friendships. They fueled the experiments that we conducted with living and loving, eating and dreaming, doing and having.

I was studious enough in college eventually to become a professor myself, but “studious” didn’t exactly mean “serious.” Rather, like Feminist Ryan Gosling, my college friends and I explored theory by yoking the serious to the silly, the obscure and the corny, the dense with the glib. We were cognizant that the world of perfect ideas shares an open border with the world of imperfect people—those who are impressed with their own cleverness, who meant to finish the reading between classes but maybe didn’t get to it, or whose thinking isn’t always motivated by what’s above the neck. Sure, some people are interested in theory for the big ideas, the great learning, or the knowledge it promises; but like Feminist Ryan Gosling, my college friends and I were interested in theory for what we could do with it.

Me in 1998 (Courtesy http://feministryangosling.tumblr.com/)

The following chapters elaborate some episodes from my youthful engagements with theory. But as with so many memorable activities, those engagements move in a few directions at once: you go somewhere, somewhere moves you, you step forward together. Along the way, I’ll explain a little bit about what theory is, but the real objective of this short book is to explain some of how engaging with theory feels. Because I believe that feelings are best represented from the perspective of what it might be like to have them, the story will be peppered with anecdotes and tales and snippets from the youth I spent hungrily reading some really difficult books I mistook for the nourishment that they nonetheless became. All the things I’ll tell you really happened, but what you’re reading is not a memoir. Rather, anecdotes about myself are offered up as particular examples, in which I hope the reader will be able to better locate something more general.1

***

While there could arguably be an infinite number of feelings associated with theory, the ones dilated upon in what follows are some of those I associate with what academics like to call discipline—that is, with the experience of training for mastery in the terms and codes of a particular branch of knowledge. That process of discipline usually finds the energies that come with things like excitement, curiosity, and ambition in tension with those that come with other things like self-doubt, futility, and shame. It amounts, as I’ll explain more in chapter 1, to a kind of thesis-antithesis narrative. For now, suffice it to say that though my contradictory feelings about theory owe a lot to my particular experiences (times, places, classes, teachers, lovers, friends, situations), the wager of this book is that similar feelings—similar pleasures and frustrations, similar contradictions—tend to crop up in experiences that are not mine at all.

Such, at least, is part of what we can see with Feminist Ryan Gosling. My college years were more than a decade gone when this meme first appeared, but the resonances between the way this meme and I attempted to project academic theory onto the world as we each found it support the idea that my feelings being disciplined by theory are far from unique. And while much of my initiation to theory happened at UC Santa Cruz, this particular location—and indeed many of the wonderful people I found there—nonetheless proves incidental to the larger claims I’m making about how theory feels. Had I been studying theory at any number of other colleges or universities—as friends hailing from Oberlin or Brown, Wesleyan or Iowa, Irvine or Swarthmore, all assure me—the outline of the story would be largely the same.

What couldn’t entirely be changed without altering how theory felt to us isn’t so much the place as the time. The fluorescence around ideas that runs through my story really became possible in the 1990s—at a particular moment in collegiate education in the United States, at a particular moment in the culture. Ours was not the theory of the Seventies, all phenomenology and structuralism, nor the theory of the Eighties, caught between deconstruction and Marxist feminism. Rather, theory in the Nineties was busy gathering an elite and increasingly canonical corps of French poststructuralism (often taught in these years for the first time as a required course for an undergraduate major like English or Comparative Literature) and spinning it headlong into the political fracas of the day: sex and AIDS and ACT UP; women of color feminism, black Marxism, the post-civil-rights generation and its many “firsts”; the end of the Cold War, the rethinking of the three worlds, nations and nationalism, decolonization; postmodernism in art, architecture, fashion, and film. In the Eighties, theory wrapped itself around academe, but in the Nineties, theory spilled out into the culture and the world. Or, to paraphrase Walter Benjamin, there is no document of theory in the Nineties that is not at the same time a document of the context of the Nineties.

It’s that last point that the following chapters will stress. Yes, the process of learning about language, power, and history from a particular canon of theorists, and of imitating the singular idiolect in which they wrote, gave my friends and me a way of imagining our own lives and futures. But if it gave us a way of understanding something about the world, the world also gave us occasions for understanding theory. Along the way, we developed a rich sense and a robust language for understanding life as we found it and for how we were already living it out. The frequent battle cry of theory’s detractors is “How does this apply to the real world?” It was clear to us even then that such detractors had missed the point.

The one important qualification that came to me in the years since I was in college, however, is that the real world has a way of changing. Contexts shift. If what follows is, according to the preceding outline, a story of Gen X, a story about what theory meant for those of us who got lost between the Boomers and the Millennials, it’s at the same time an attempt to think through what theory might mean now that the Nineties are well over. A story driven by examples from reading theory back then, my narrative also considers latter-day instances (including memes like Feminist Ryan Gosling) in order to understand the extent to which “then” lives on now. Inasmuch as it does live on—inasmuch, in other words, as the present is always built on the past—my story attempts to look back in order to look forward. This is a book about reading theory in the Nineties for people who are reading theory now.

Individual chapters track five of the feelings that reading through, learning about, and living with theory made and make us feel: silly, stupid, sexy, seething, and stuck. Each chapter tells stories about its respective feeling as a way of elaborating the affective and intellectual work that theory did for me as a young person—and that, I’ll wager, theory did for many of my peers and may still do for many more of its students. The five chapters roughly alternate between the lighter and the more serious aspects of being disciplined by theory.

Chapter 1, “Silly Theory,” looks at the memes and jokes and goofball antics that move the high into the realm of the low. It takes seriously the scenes of humor and play where learning takes place, and it thinks about how missing the serious theoretical point of your reading can, all the same, be a way of arriving at an equally significant point.

Chapter 2, “Stupid Theory,” reminds us that learning isn’t all play and that one of the things that happens when people are confronted with intimidatingly abstract ideas is that they feel dumb. And resentful. This chapter underlines that one of theory’s lessons is how to live with patience, how to handle something you don’t understand.

Some things that we do not understand we still very much enjoy, and this possibility is the subject of chapter 3, “Sexy Theory.” It looks at another ineluctable aspect of being young: how we learn to have preferences, how we begin to discriminate among love objects, and how one object becomes a way to love another.

Chapter 4, “Seething Theory,” watches as love inevitably turns to rage, as debate and argument and even genuine fighting become ways we explore our attachments to ideas that feel anything but abstract. This chapter tracks some of the ways that the feelings we hold deep are and aren’t ours—or, rather, how we learn to borrow anger and take on existing conflicts as a way to refine our own senses of the ideas and politics we care about.

Finally, chapter 5, “Stuck Theory,” circles back to the problem of knowing versus doing, the question of how to put theory into practice. I stand by my convictions that reading theory in my youth was a way of being in the world and that the context of that world came to bear on theory. But that doesn’t mean we solved it all, and it certainly doesn’t mean that on the days not long after college when the Twin Towers fell, or when the United States invaded Iraq, theory could ever have been a big enough consolation or a powerful enough counterpoint to mendacious lies dressed up lethally as intelligence. Among the many things that happened on September 11, 2001, the Nineties finally, completely ended.

Avidly Reads Theory is not an introduction to theory. Many useful such guides exist, but you shouldn’t have to consult them to appreciate the story I’m telling. All this story requires is a willingness to imagine how ideas have the power to become something more tangible and, I suppose, to imagine how it’s possible to be so young and so foolhardy as to court life advice from schoolwork. What follows is a story about the emotional lives of ideas.