1

Silly Theory

Some years ago, I found myself at a twenty-four-hour vegetarian diner in a California college town, breakfasting with a dear friend. We had ordered coffee, but the main course was psychoanalysis. “You can’t read Lacan without Hegel,” I assured her earnestly. She broke into a grin, paused for a brief, dramatic moment, and then sang my words back to me, to the tune of Keith Richards and Mick Jagger’s “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” hitting the second syllable of “Hegel” in a flat F.

College brimmed with capital-T theory: that interdisciplinary set of literary and critical writings that blend Continental philosophy with qualitative sociology and theories of “the text.” As generations of college students have noted, theory is often stylistically difficult and menacingly abstract, as obscure to the uninitiated as any other kind of heavy thinking, and yet way too cool to be called simply “philosophy.” My friends and I were theory heads. We elected to read the Germanic sentences penned by French absurdists, and we had a great time doing so. We were young and smug and deconstructed. In the classrooms and bookshops of fin-de-siècle California, we staked the foundation for our educations in an incisive critique of foundationalist thinking. We saw the irony, and we embraced it with the kind of reflexive detachment that today’s fashionistas could only hope to conjure when they declare that something is “so Nineties.”

Detached as it may have been, our experience of reading theory was far from dry. As the Jagger-cum-Lacan anecdote suggests, my college years embraced theory as though participating in what Lauren Berlant (in an essay I read over and over) called “a counter-politics of the silly object.” We had a million puns (Kristeva? Whateva! Bourdieu? Bored me too! Understand deconstruction? You de Man!) We plotted the names of bands (Foucault’s Hos, The Heidegrrrls) and cocktails (notably the Pink Freud, whose recipe I don’t think we ever perfected but nearly all of whose iterations involved a banana). I wrote the treatment for a play called “Rendt: A Musical about AID,” which replaced the transvestite character in Jonathan Larson’s Broadway smash with a young, bohemian Hannah Arendt (also played by a transvestite). We created Lacanian drinking games for our favorite movies (“sip your Pink Freud when being and having are confused in a condition of lack”). And in perhaps my most starstruck celebrity sighting ever, I one day had the thrill of walking through a Longs Drugstore three paces behind Angela Davis, who (perhaps unaware of me, perhaps all too used to being followed) appeared to be doing nothing more revolutionary than buying cold medicine.

Playing silly games with serious ideas provided us with a way to lavish attention on the scene of our learning. It seems clear in retrospect that the actions of my college friends and me were not about theory, the object, but about creating a reflexive awareness of the context in which that object could (in fact did) circulate: through the space of early-morning diners and late-night parties, through the hands of amateur mixologists and bargain shoppers, and through the educational transformations of public school graduates into fledgling intellectuals. We aimed for some reciprocity between the serious things we were learning in school and rather less serious register in which we were living our lives outside of it.

It’s in the same silly spirit that my students and their peers now turn highbrow theoretical ideas into goofy memes. Tired puns (advertisements for Freudian slippers) and doctored images (Friedrich Engels on the cover of “Cosmarxpolitan” magazine) occupy whole pages or feeds on platforms like Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter. I read them with a burning sense of having missed out on their expansion into a visual domain of the kind of bad jokes that require a considerable education for one to earn the pleasure of finding them resoundingly stupid. Still, other contemporary attempts at silliness are more direct and more reminiscent of the jokes my friends and I made in college. Or, as a very bright young woman once wrote, unbidden, on her final exam for my intro theory course, “Your mama’s so classless, she could be a Marxist utopia.”

***

The grand alchemy for turning ideas into lives began, in my case, entirely inauspiciously. Introduction to Literary Theory was the only required class for my undergraduate major. It was offered every term, though the course varied by instructor, usually combining some elements of a survey—that is, some background in twentieth-century theories of language and representation—with emphasis on the particular professor’s specialty. In the spring of my sophomore year, the professor happened to be a specialist in Russian modernism, and we spent half of the ten-week quarter studying theories of Russian formalism, which, for all their avant-garde provocation, had lost more than a little something in translation.

For the in-class midterm, our professor, straining for relevance to our contemporary situation, screened the video for the even-then-ignoble pop band Hanson’s fourth single, “Weird,” to be followed by an analytical essay in blue book. If this was an effort to connect theory to life, it faltered considerably. What I learned was, rather, an astonishing lesson in the coordination of formal and critical incoherence, because none of it made any sense. (The Hanson brothers, whatever more generous interpreters might find their merits to be, bear precious little on the theories of Viktor Shklovsky.) As pedagogical tragedies go, it was ordinary enough. Though when the class implausibly screened the very same benighted Hanson video again in the last week of the term, at the behest of a guest lecturer who seemed not to know we’d already been asked to view and analyze it, what had once been tragedy was now clearly farce. It all felt pretty silly, but not in a good way. If there was a lesson here, it had to do with how not to live.

Hanson, “Weird,” cover art for the Europe and UK single, 1998 (Courtesy Mercury Records)

The thing that piqued my interest that term had nothing to do with all these things we were focusing on. It was instead a reading sneaked into the sixth or seventh week, an essay by Jacques Derrida called “White Mythology.” In what I now recognize as a classic of poststructuralist high theory, Derrida’s sixty-page tour de force presents a rigorous deconstruction of the distinction between content and style in philosophical writing, showing how you can’t have content without style and vice versa, how the two concepts fundamentally depend on each other, and ultimately going so far as to suggest that there is only a delusive difference between the language we use to represent reality and reality itself.

But I missed all that. I didn’t walk away from the essay appreciating Derrida’s critique of representation, which, arguably, is the whole point. What intrigued me, instead, was the operation of deconstruction. It fascinated me to think about dependence in Derrida’s terms. Though generally unconcerned with how philosophical discourse worked, I was alive to the possibility that reality and the representation of reality depend on each other, such that reality is not meaningful without representation, and therefore that reality is not better than representation, for each constitutes the other.

My imagination moved from representation to infinity. All around me, conceptual hierarchies began to crumble. Men weren’t better than women; humans weren’t superior to animals; civilization was no better than barbarism. The arbitrariness of it all felt wild and enabling. Here was a use for the fin-de-siècle ennui that I spent the Nineties feeling anyway. Here was a version of the absurd and studied detachment that my friends and I cultivated during our off hours. Here was an account of the arbitrariness that I was pretty sure governed our world, but elevated and turned back on the world in a way that made the world as I found it a pretty silly place. Here was some justification that it really didn’t matter whether you prioritized the authority of your teachers and their books or the dreams and longings of your peers. If you’d asked me as a college sophomore what “White Mythology” was about, I would probably, sincerely, have told you it was a manifesto for Revolution. My reading was a misreading, but what it lacked in precision it sure gained in verve. Here was a way to be.

It was not an accident, perhaps, that the scene of my seduction by theory was more or less extracurricular. Though “White Mythology” was on the syllabus, the class didn’t much discuss it, and certainly not with the rigor that I now know it would require. On first reading, I didn’t properly understand what I was reading and so was able to do that most magical thing that one sometimes does as a student or reader: I made it mean what I needed it to mean. This, I think, was one of the keys to “theory.” To read rigorously, precisely, clearly—these things were among our aspirations, yet they were not what we as student readers usually accomplished. Instead, the imprecisions in our reading and learning were the story—they were a big part of what we meant by “theory.” We were on a road toward abstract thinking, but the real fun was getting there. And we had a lot of fun.

***

Derrida’s were not the only theories we were reading in college that had anticipated the possibility that we might get silly with serious ideas. Doing the opposite of what was intended with an idea was, at the least, a storied tradition for certain strains of critical thinking. I’m referring here to dialectics, that ancient mode of tripartite argument that reached its apex with German idealism and therefore remains associated for modern readers with Hegel and Marx. By definition, dialectical arguments have three steps: a thesis, wherein an idea is posited, an antithesis, wherein the thesis is negated, and a synthesis, wherein the contradictions between the thesis and the antithesis are suspended and blended into a new proposition. (“What’s a Marxist?” asks an old joke. “Someone who can only count to three!”) The second step, the antithetical move or dialectical negation, was best loved by twentieth-century Marxism, and it certainly jived with the ways that we irreverent theory heads wanted to negate the seriousness of theory and make it into something more fun.

At the time, however, we largely failed to make the connections between dialectical negation and just goofing. This failure back in the day surely had something to do with the day itself, as my college years fit squarely in that scant decade between the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the fall of the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001. Between these two falls there came a glorious spring of optimism around globalization in both its economic and multicultural forms. These were victories for capitalism and, thereby, were understood as blows to the possibilities of actually existing socialism. Many Marxists doubled down and tried hard to rethink how human emancipation might look in an age that Susan Buck-Morss characterized as “the passing of mass utopia in east and west.” Marxists, in other words, got more serious.

Not that they’d exactly been jokesters. In fact, few theorists of any persuasion were ever more legendarily serious than the famed Frankfurt School Marxist Theodor Adorno. He had been born the only child of a well-to-do German family in 1903, with a secular Jewish father and a Catholic mother. Adorno was her family name, and its original hyphenation to the patronymic—Wiesengrund-Adorno—was mutilated in the son’s Nazi-fleeing application for US citizenship, rechristening him Theodor W. Adorno when he was already well into his thirties. The family name was far from the only thing Adorno lost in the war, but the episode rather neatly allegorizes the collapse of his turn-of-the-century idyllic upbringing when one realizes that the sacrificed name, Wiesengrund, literally means “meadow land.” How could Adorno’s mature thought be anything but marked by an almost fatal seriousness?

To add to the ignominy of having to seek exile for the offense of being only technically Jewish, Adorno had the complicated misfortune to end up in Pacific Palisades in the 1940s, down the coast from Malibu, where he could view the rise of capitalist techno-modernity from the belly of the Hollywood beast. His most famous exposition from the period is Dialectic of Enlightenment, a book of essays he coauthored with his friend, former teacher, and fellow émigré Max Horkheimer. It’s core theoretical chapter, “The Culture Industry,” distills in no uncertain terms how the industrial products of the postwar United States threaten human culture as we know it.

Culture, after all, is the shared activity of people, while industry is large-scale and profit-driven manufacturing. When culture becomes industry—when we buy recorded music instead of learning to play or when we pay for a movie ticket instead of escaping into our own reveries—we reside in a world where there is little difference between a rom-com and a bomb. Both, Adorno and Horkheimer argue, are industrial products fitted for mass consumption, designed to make money regardless of what they destroy. With a take-no-prisoners pessimism equaled only by the authors’ rhetorical skill, “The Culture Industry” manages to pack a whole dialectical argument into its three-word title.

Serious problems require serious solutions, yet the best shield Adorno and Horkheimer have against the machinations of the culture industry is to identify the problem, to name it, to expose it to view. Adorno and Horkheimer place faith in exposure. Though they stop short of saying so, their essay itself is about the only kind of resistance they can muster, insofar as the rarefied critical and philosophical writings of intellectuals do not, by design, accede to the level of mass appeal. And, as far as they are concerned, mass appeal has ruined just about everything else; or, in their own concluding words, even “personality scarcely signifies anything more than shining white teeth and freedom from body odor and emotions.”

While Adorno and Horkheimer are not trying to be silly (witty, perhaps, but never silly), the wonderful pathos of juxtaposing BO and emotion, held in common by the fact that one might equally want to be free of each, is the kind of comparison one might expect from the likes not of a critic but of a comic, say an Amy Schumer (perhaps only coincidentally also a secular Jew whose comparatively idyllic early life was disrupted by major losses of wealth and prestige). Yet the temptation to smile or even laugh when reading a sentence like this from Adorno’s corpus (and there are lots of them) has something to do with the fantastic accuracy of his diagnoses, which so successfully expose the pitfalls of capitalist techno-modernity. Adorno calls an unbearable world by its name, and we laugh not because we fail to believe him but because we believe him entirely. One of the functions of humor, after all, is to make bearable something that basically isn’t or shouldn’t be.

***

Had Adorno lived that long, he would perhaps have directed his truth-telling powers to elucidate how life in the Nineties became unbearable. Instead it has been largely in retrospect that other analysts came to see clearly the decade’s patterns of economic redistribution, as dot-com and real estate booms made speculators rich, while welfare reforms and mass incarceration stripped many Americans of what remained of their social safety net. On the ground, however, the great indicator of trouble was the widespread cultivation of a certain attitude. When one left the house in the Nineties, it was not while sporting an Adornian faith in exposure but rather outfitted in the grand defensive armor of irony.

Irony was so everywhere in this decade that Alanis Morissette topped the charts in 1996 with a song called “Ironic” (which, ironically, had a patently incorrect definition of irony as its central conceit—you cannot make this up). Germane to our story, moreover, is the way that all this irony had a particularly blunting effect on the force of Marxist critique and, especially, on its faith in exposure. What could revealing the secret machinations of ideology possibly mean for people so détaché that they couldn’t be shocked? Insights like Adorno’s began to sound hollow in the ears of some more ironically attuned readers.

Looking at the Nineties through irony-colored glasses allowed us to feign boredom with the more unbearable aspects of the truths to which we were exposed. So, for example, when the button fell off a college friend’s jacket, she joked about how they don’t make child labor like they used to; or as people wondered about the safety of newly marketed gadgets like cell phones, my friends began to call them “brain cancer phones”; or again when a multiplex theater opened up opposite the independent local movie theater in our college town, we poked out of our ennui long enough to ask whether tonight we’d go to see a real movie or a corporate one. The examples sound trivial, juvenile, and a bit callous, and our irony was all of those things. Moreover, directing our irony (as in these actual examples from my youth) at economic and technological aspects of our globalizing world positioned irony neatly, if unintentionally, as a force opposed to Adornian exposure-based insight. We weren’t critiquing the ascent of late capitalism; we were finding the language that would let us live in it.

Perhaps it was a function of coming of intellectual age in ironic times, but I never managed to identify myself as a Marxist. I was, nonetheless, very drawn to the writings of Marx and his inheritors, and for a couple of months in college I dreamed of writing a thesis that updated Marxism for the great age of irony. How can one place faith in exposure and the knowledge it yields, I wondered, if one lives in a world where everyone was ironic and detached and knew it all already? In the end, I abandoned the thesis because the question seemed too large. (And also because I could not read German and therefore could not engage with the likes of Adorno in the original. Powerlessness and pedantry can be passionate bedfellows.) Instead of writing that thesis, I just kept casually reading Marxist theory and tried to make peace with the fact that I would occasionally find it over-the-top and therefore a little funny.

Unbeknownst to college me, however, a related question had already been the subject of a UC Santa Cruz undergraduate thesis just a few years prior. Partially published in 1996 as “Capitalism and Schizophrenia: Contemporary Visual Culture and the Acceleration of Identity Formation/Dissolution” in the online journal Negations, Jonah Peretti’s thesis argued that late capitalism, particularly by way of advertising, solicits a person’s identifications and encourages them to form, dissolve, and re-form identities with great rapidity. The effect, he observes, is an acceleration in shopping, as the rate at which we consume tracks with the rates at which we attach ourselves to the objects with which we identify; but, he concludes, there is no reason “that radical groups could not use similar methods to challenge capitalism and develop alternative collective identities.” Particularly prescient here is Peretti’s sense that opting out of the psychological and aesthetic machinery of late capitalism—toward which Adorno and Horkheimer seem to aspire or along which we ironic Nineties intellectuals tried to skirt—was not the path. Instead, the only way out is through, and Peretti embraced rather than avoided. Ten years after he published his thesis, and coincidentally just months after I finished grad school and hit the unemployment line, Peretti put his theory into practice and founded a website to track viral media, which has since become Buzzfeed.

Perhaps theory prepared us for the memes after all.

Thesis: You can put serious things like theory into silly context

Media innovations like Buzzfeed and Twitter have left readers of theory in a world that increasingly measures messages in characters rather than paragraphs. Many media-literate (and especially younger) theory heads are ever more inclined to see that philosophical ideas can be pithy, aphoristic, and even pertinent to the kinds of banalities that swell social media feeds. Hence the existence of Chaka Lacan, whose name is a long-lived joke but whose short-lived Twitter persona (billed as “an interstitial space between hair mousse and the I”) includes mashed-up gems from its two namesakes, like “Regarding this locus of the Other, of one sex as Other, what does this allow us to posit? I am every woman; it’s all in me.” Similarly and more prolifically, Kim Kierkegaardashian fuses the philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard with the tweets and observations of Kim Kardashian, to produce rather stunning pronouncements like “Because my dress isn’t butt-tight, faith alone holds together the cleavages of existence.” What’s most astonishing about such a claim, of course, is that it illustrates Kardashian’s outfit and Kierkegaard’s input far more succinctly than either could explain for themselves. The ideas contained in these tweets matter, but they matter less than the medium of their expression. The ultimate context for these experiments is their form: theory isn’t designed as a sound bite, but not because it couldn’t be.

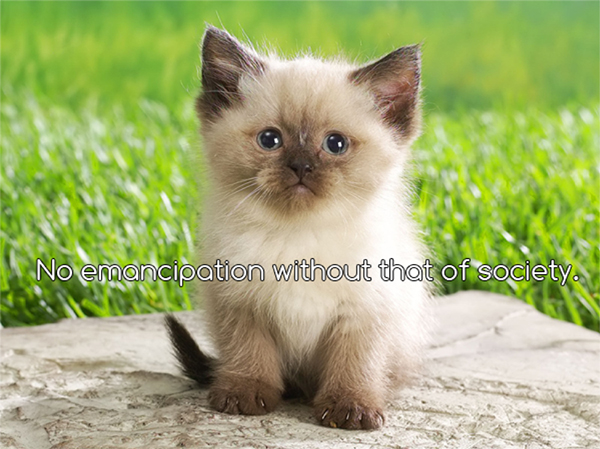

This lesson about context is not, however, one to which all people readily assent. Indeed, I have talked with some very smart folks who argue instead that an interest in acknowledging the scenes of theory’s circulation is belittling—whether because it prioritizes context over text or because it forces lofty philosophical ideas to accommodate late-capitalist realism. Perhaps no meme is more likely to encourage such conclusions than Adorno Cats, a now-defunct Tumblr that pitilessly superimposes biting quotations from Adorno’s critical writings onto color-enhanced photos of tiny kittens. It may be difficult not to look at a fluffy Siamese kitty captioned with “No emancipation without that of society”—the much-quoted conclusion to the 111th chapter of Minima Moralia (whose proper topic, lest we forget, is Greek myth, sexism, and Hegel)—and not see a deliberate attempt to diffuse Adorno’s dialectical critique in the overlarge azure eyes of feline charm.

Such an interpretation, however, is decidedly un-Adornian. Ever alert to the machinations of ideology in minute locations, Adorno once devoted a substantial essay to his unbridled distaste for the LA Times horoscope columnist (an essay, I should confess, that I have never finished because every attempt at reading it leaves me laughing distractedly). Filling in the gap between culture and industry, the bland experience of individuals and the nefarious rationalizations of society, Adorno taught generations of thinkers to move fearlessly across seemingly disparate registers in order to expose the face of ideology—and there is no reason to suppose that he would make an exception when that face has whiskers. The cuteness of Adorno Cats, then, can be understood less as a bid for mastery over theory than as a complex embrace of theory’s great dialectic of earnestness and silliness. Moreover, the cute, writes Sianne Ngai in a formidable kind of sequel to Adorno’s aesthetic theory, is itself dialectical: something so diminutive invites us to imagine that we can control it, while also controlling us by provoking involuntary cooing. Only in our fantasies can mastery be a one-way street.

Antithesis: It’s not context that makes theory silly but theory itself

Contrary to my previous proposition, examples like Chaka Lacan and Adorno Cats suggest that the currency of silliness in the vicinity of theory may have to do less with the uses to which theory can be put than with something that may inhere in theory itself. If that’s true, then silliness is not an attempt to take theory down; rather, seriousness is an attempt to guard against the queer material of which theory is made—that big, difficult idea that always threatens to turn into a puddle of soft and ridiculous goo. The tonal seriousness and prosaic difficulty that characterizes theory’s most celebrated practitioners and that is slavishly imitated by many zealous graduate students (including, as we will see in the next chapter, myself) is but a recent manifestation of the age-old paradox of trying to harness potential by denying its volatility. To secure themselves against volatility, serious practitioners of theory often become defensively prone toward obscure platitudes and dry clichés—toward a jargon-laden in-speak, in other words, that somewhere along the way forgot that any seriousness that studiously ignores unseriousness is rather hard to take seriously.

Quite in spite of any aspiration to seriousness on the part of its readers, theory’s volatility persists. I cannot be the only person whose attempts to read Martin Heidegger have left me feeling like I am aboard the Hindenburg. I cannot be the only person who has giggled while reading Gilles Deleuze’s unblinking analysis of Antonin Artaud’s pronouncement that “All writing is PIG SHIT.” I could not be the only student who was crippled with panic about what to wear to class on the day we were discussing Judith Butler’s theories of gender performance. I know I am not the only person who has swooned while reading some of the more tender of Roland Barthes’s caressing fragments on love.

Yet I freely admit my complicity with the silly movement of theory’s dialectic, because, contra my more serious theoretical fam, I am not aware of any rule that says dialectics are most true when they tend toward the tragic. No less an authority on dialectical history than Marx himself posited that what appears once as tragedy appears a second time as farce. And, despite having lived at a time before the Hanson brothers appeared on anyone’s theory midterm, Marx still knew that farce, properly executed, is pretty silly.

Synthesis: Silly theory and serious theory together make Theory

Acknowledging the silly in theory challenges not only the in-speakyness of theoretical jargon that takes theory too seriously but also the kind of demotic countersnobbery that dismisses theory out of hand for being too difficult. Those who are stationed irretrievably far into the antidifficulty camp tend to suppose that plain speech and realist genres count as neutral representations. The problem with this line of thinking is that the generic claims of normative realism, consequential though they may be, are little more than claims that representation ought to be banal. That is, the inverse of imagining that theory is too difficult tends to be imagining that what often counts as more basic is therefore more true, as though our culture’s clichés—houses with white picket fences, politicians who tell it to you straight, beauty accentuated by its flaws, or career women who have it all—circulate in representation first and foremost because they really and unproblematically exist for some statistical majority. Instead, these clichés are as made up as Monique Wittig thought women’s bodies were—which is to say, totally.

By this line of thinking, there is no objective reason why anyone should automatically understand the cuteness of a LOL Cat, any more or less than one should understand the thunderous exasperation of one of Adorno’s monodies to the world that was cruelly sacrificed in war. Understanding either requires certain kinds of literacies that would enable you to recognize the idiom in which each operates. What’s interesting, however, is that neither a theoretical bon mot nor a meme belongs exclusively to the domain of realism. Words like “realistic” or “normal” apply as little to Minima Moralia as they do to LOL Cats.

Moreover, I would argue that these words do not apply to these texts for what are in fact the same reasons: both texts are highly idiosyncratic appeals to general experience, both combine word and image to produce incongruous pictures of the everyday, both want something from reality that it contains primarily in fragments. To see only that each operates in a different idiom is, I would say, rather foolishly to misrecognize that both are trying to give voice to something that we readers of these texts have perhaps intuited but have heretofore been without a way to represent. Both begin with some familiar aspect of the world, and both use the recontextualizing arts of combination and juxtaposition to push off from what we think, toward what we have not yet thought.

The most valuable aspect of silliness, then, is that it works aslant both theory’s aspirations to seriousness and realism’s aspirations to referential simplicity. It reminds us that what is at stake in reading theory is not just what the theory says but also what we do with it—whether that means penning a devastating critique or downing a Pink Freud. In the act of mashing up Chaka Khan with Jacques Lacan, we’re doing theory; but, more specifically, we’re doing the work of making sense out of our less-than-theoretical world. The silliness of theory makes that work less urgent, though no less bracing. It enables readers of theory to relate theoretical ideas to the very world in which they encounter those ideas, to see how theory does and doesn’t illuminate their realities, and to begin to put the pieces together. Here perhaps is the greatest lesson that theory can teach us about the world: some assembly is required. And who knows? It may be true that you can’t read Lacan without Hegel. But if you try sometimes, you just might find, you get what you read.