3

Sexy Theory

If Kant was the local hero of graduate school at the turn of the millennium, Michel Foucault was the patron saint of the Nineties liberal arts education. Kant we read abstractly, without attention to historical context; but Foucault encouraged us to think about the historical context for anything and everything. Whereas Kant, with his powdered wig and famously unvarying daily routine, was not very sexy, Foucault, with his bald pate and his leather jacket, was a walking, talking, thinking sexpot.

Part of Foucault’s sex appeal had to do with the fact that he was more or less a contemporary. Someone like Kant or even Marx belonged to the ages, but Foucault had died only recently, in 1984. Granted, most people of my generation were neither old enough nor educated enough to have seriously studied his work by the time of his death, but that didn’t change the fact that the separation between us and him was often no bigger than a single degree. Foucault spent a chunk of the early Eighties lecturing at Berkeley and visiting other US universities, where many of my professors had heard, met, or studied with him at one point or another. Plus, most of us in college in, say, 1997, had memories of 1984. Even if those memories were not of Foucault, they still made Foucault feel closer to us, proximate to the world we lived in.

The story of Foucault’s visit to UC Santa Cruz went like this: he was in town for one speech only, and it was to be delivered in one of the large lecture halls on campus. He took to the stage and found his faculty hosts seated toward the front rows, with students and others farther back. Following the highfalutin academic style we Californians attributed to Foucault’s native France, he lectured to those first rows, addressing his peers on the faculty. At some point during the talk, however, he looked up and caught the glance of a handsome graduate student. Foucault locked eyes with the young man, smiled, and then continued talking in the direction of the faculty. But he looked up again and held the student’s gaze longer. And again, and even longer. By the end of the lecture, Foucault was speaking, with a smile on his face, only to the handsome graduate student in the back. Meanwhile, the handsome graduate student’s very tall boyfriend had not failed to notice and was exhibiting defensive body language, putting his arm around his lover. It was told that the very tall boyfriend was following a course in Peace and Justice Studies, and so the event was shorthanded as “the time Foucault almost got beaten up by a seven-foot Quaker.” In the overeager fashion I associate profoundly with my fledgling years in academia, the story’s punch line was also the title.

I heard this story from one of my classmates, who was my age and so had definitely not been there. I repeat it, as I have over the years, without myself having been there. It is incredibly likely that all or part of this story is apocryphal. (I have, in fact, not been able to verify that Foucault ever visited UC Santa Cruz.) But who cares? The truth of the story is the clear impression it gives that Foucault was for us not only a living theorist but a particularly alive one. If being a student of theory required one to prostrate oneself before great thinkers, there was something incredibly pleasing in the idea that one of those great thinkers might make a dirty joke about prostration. We took Foucault to be that guy, and we loved him for it. Whether or not he was that guy, the fact that we needed him to be offers a useful reminder that desire and pleasure are part of the story of studying theory.

***

The first volume of Foucault’s The History of Sexuality filled my time one summer day on the bus-to-train-to-ferry-to-bus trip between college and my parents’ house. The reading was challenging but probably less so than my painfully self-conscious contemplation of what the strangers with whom I shared public transportation might see if they glanced in my direction. Half my time was spent looking at my book and the other half furtively glancing around to see if anyone was looking at me reading this book. I wondered what others might see in part because I had no definite sense, sitting there reading Foucault, what I was going for: gay? student? sophisticated reader of really difficult theory books? (My total lack of assurance about whether there was any overlap on that Venn diagram seems, in retrospect, sweet.) If my reading a book with “Sexuality” in the title conjured any intrigue, my fellow passengers managed to play their cards close. By the time I finished the fourth leg of my journey, I had to admit that no one appeared to have glanced in my direction.

If they had, however, it seemed pretty obvious to me that they should have recognized a book by Foucault as a gay book. All these years later, in a world where some public figures simply are gay, Foucault’s out-and-queer-ness probably seems rather far from the most important thing about him. But you have to recall that in the Nineties there were no out gay news anchors or A-list actors or politicians or professional sports players. There was just one openly gay reality TV star, and he was the first functional gay adult whose story many Americans had ever gotten to know. In 1999, James Hormel began serving as the first openly gay person appointed as a US ambassador, and if you have any doubts that the controversial nature of his appointment had to do with the national mainstreaming of homophobia in those years, recall that his post was to nowhere more diplomatically significant than Luxembourg.

Such a world, needless to say, made little room for out gay philosophers. And so because in the Nineties, on the one hand, Foucault’s writings were having an impact on nearly every discipline of study in the humanities and social sciences and, on the other, the people who got to have an impact were rarely gay, Foucault’s gayness loomed, symbolic and large. It felt, to use a Foucauldian word, political, and the politics of this knowledge framed how many of us thought about Foucault. At the same time, that frame did little to explain his theories, and, indeed, there is a real extent to which Foucault mistrusted the political value placed on biographical facts for theoretical interpretation. He wasn’t wrong to do so.

After Foucault died in 1984, three biographies appeared in short order: Didier Eribon’s Michel Foucault (1989; translated into English in 1991), David Macey’s The Lives of Michel Foucault (1993), and James Miller’s The Passion of Michel Foucault (1993). All three discussed Foucault’s homosexuality and its impact on his life and thought, albeit to very different ends. Eribon did so affirmatively but guardedly (though, written from within a particularly AIDS-phobic moment in French culture, courageously), and Macey did so frankly, matter-of-factly, as though homosexuality simply numbered among a biographer’s challenges for empirical reconstruction. Miller, however, did so with moments of undisguised prurience toward the queer worlds that his narrative exposed to the light of the heteronormative day. Published shortly thereafter, David Halperin’s Saint Foucault (1995) raced in with a rebuttal to Miller’s biography, as lengthy as it was scathing, detailing the ways that Foucault’s aversion to the biographical fallacy was precisely an aversion to the kinds of homophobic discreditation that Miller so gamely advanced.

Many of my fellow college students admired Halperin’s book, meaning, among other things, that it must have shown up on a number of different syllabi in those years. (I didn’t read it for class but instead because a cute boy wanted me to.) I too admired the book, but my thinking about the authors I was reading nonetheless inclined toward their biographies. I wanted a gay Foucault. I was glad I had one, and I didn’t want to have to give him up in the name of theoretical consistency.

Eribon, at some level, wanted a gay Foucault too. Of the three biographers, he was the one who had been Foucault’s friend, and he justified his biography by arguing that Foucault was, on his own terms, an author: the words Foucault penned begot a discourse whose scope proved to be far larger than the writings themselves. In this way, Eribon anticipated by more than two decades the finest exposition of Foucault’s notion of the author-function, Beyoncé’s 2016 claim “You know you that bitch when you cause all this conversation.” Yet in those long-ago days when Beyoncé contended only in grade-school talent shows, Eribon already saw, correctly, that Foucault was “that bitch.” So he split the difference and wrote a book whose subject was the genesis of Foucault’s impact, as much as a study of his life. The result is a respectful and measured biography of a public figure who required a lot of privacy. Though admirable as an intellectual accomplishment, Eribon’s story also disappointed. As is the case with so many love triangles, I just wanted more of Foucault than Eribon felt he could allow me.

And so, though Foucault probably had my strongest theoretical allegiance in those days, when it came to thinking about biography, I was drawn much more toward deconstruction. Jacques Derrida, for example, advanced the notion of the “signature,” according to which all texts we write or create, by virtue of having been written or created by us, obliquely stand in for us—and therefore are to some extent about us as much as they are about their nominal topics. Paul de Man made a related claim in his bravura late essay “Autobiography as De-facement,” imagining that all writing is autobiographical but, for the same reason, all autobiography is merely writing. Deconstruction, in other words, along with my laxity for logical consistency and my eclectic reading habits, got me around the part where reading Foucault because of some detail in his biography bordered on misreading Foucault.

It’s tempting to imagine, however, that what deconstruction says about writing is also true of reading. Did my eclectic reading habits, willfully mixing up different schemata and theoretical discourses, amount somehow to my own signature, my own way of finding words, not just for representation and power and history but also for myself? A sympathetic interpretation of the story of my attempt to read Foucault on public transit might point in that direction. Whatever else I may have learned from The History of Sexuality (actually, quite a lot), I was reading it that day on the bus, train, and ferry because it seemed to me like a gay book and, in the act of reading a gay book, I wanted to see how I myself might be read.

One of my recurrent jokes in those less-than-surefooted years was that my sexual orientation was theoretical. It wasn’t funny, as jokes go, or strictly true, but it got two things right. First, it named the way that theory, for me as a student, was a libidinal object, something in which my investments were not purely intellectual; and second, it pointed to the ways that sexual orientation—the part of who we are that depends on what we’re drawn toward—is defined not just by the reality of how our needs get satisfied but equally by the aspirational horizons of our desires.

Desire is part of the scene of reading theory, and desire is unruly. One doesn’t always want what one should, and one reads texts with fidelity to one’s own wants as much as (sometimes more than) to whatever the texts themselves happen to claim. What aligned my desire for Foucault’s text into the approximate shape of a sexual desire, I think, has something to do with the tentativeness of my reading in order to be read. This desire was not the self-consciousness that Hegel describes with that term or the will-to-power that Nietzsche designates; “desire” in this context had much more the character of Freud’s ambivalent eroticism: I wanted but hardly knew what I wanted. My reading engaged in an experiment with seeing where some part of me could go, with how it felt to be or be found in a place toward which my fantasies (of who I might be, of how I might be seen) tugged me along. I started reading Foucault’s book with no idea how it would end.

***

Everyone’s sexual orientation in the Nineties couldn’t help but be a bit theoretical, and the AIDS crisis was the culprit. Sexually transmitted infections were hardly new; but suddenly one was widespread and fatal, and the people who were dying in the largest numbers were often young enough to be new to sex. At the same time, the slow and uneven public response to the epidemic signaled how aggressively the conservative Eighties were lashing back against the free-love Seventies. (At the time, we called them the Sixties, but the dates don’t check out; when people talked about “the Sixties,” they often meant something like 1967–1977—roughly, the Summer of Love to the Iranian Revolution.) In this context, sex became, to say the least, a bit complicated.

AIDS scrambled the available narratives around sex, making sex something that nearly everyone had to sort out in the abstract. Reports from the early days of the epidemic indicated that the HIV infection was (1) sexually transmitted and (2) prevalent among gay men. Just these two facts meant that all kinds of people, from educators to public health professionals to politicians to family members, suddenly had to confront the mechanics of gay male sex. It was a singular feature of the early Nineties that one could watch the nightly news and listen to segments in which correspondents and experts had a dressed-up version of a locker-room conversation: does this or that activity “count” as sex? Similarly, condoms were an ineluctable part of sex in the Nineties, and I understood in principle which kinds of situations did and did not require them years before I would have any occasion to use one myself.

The midst of the AIDS crisis was an unfortunate time to hit puberty, because it meant that one began to approach one’s own sex life at a moment when the cultural meanings for sex were under unbearable pressure. Even friends my age who were never queer or protoqueer report that in adolescence sex often seemed much more scary than fun. Well before we’d experienced its pleasures, we were confronted with the fact that sex was potentially lethal. Such a possibility amplified the already guilt-prone feelings of puberty, forcing desire to live in extra-cramped quarters with embarrassment. The AIDS crisis, as Simon Watney summed up in 1987, was not only a public health crisis, but “it involves a crisis of representation itself, a crisis over the entire framing of knowledge about the human body and its capacities for sexual pleasure.” Those of us a bit younger than Watney came of age in a world where love felt really, really far from free.

The small silver lining attending this scrambling of prior generations’ narratives about sex was the chance it provided to make new narratives. By the time I got to college, there were a good number of examples: Audre Lorde arguing that the erotic was a source of political as well as personal power or Douglas Crimp suggesting that safer sex practices showcased the resourcefulness of queers in a homophobic world or Gloria Anzaldúa sorting out the jumbled ways that sexuality gets lived in relation to gender, race, religion, and geography. I was particularly moved when I watched Marlon Riggs’s experimental film Tongues Untied, which introduced me to Essex Hemphill’s poetry and, especially, the incantatory line “Now we think / As we fuck,” where “as” means like but also while. My all-time favorite text from that period is Cheryl Dunye’s film The Watermelon Woman, an early contribution to the “mockumentary” genre, in which a black butch lesbian aspiring filmmaker in an interracial relationship pieces together—from scrapbooks, chance interviews, and the credit reels of old Hollywood movies—the story of a black butch lesbian aspiring actor in an interracial relationship. Sometimes, the film tells us, you have to create your own history.

All of these texts thought beautifully, boldly, and abstractly about sex and its place in a broader world. Accordingly, these texts looked to us like theory, and we ranked them with and read them alongside other so-called high theorists like Derrida and Adorno. It was clear to me even as a college student that such an assessment was not universal; I was well aware that a proper philosophy class would favor Locke’s theory of personhood over Lorde’s. But it was equally clear to me in those years that the connections between philosophy and theory and just thinking abstractly about social life were connections that I was not alone in needing to make.

***

Less than ten minutes from the end of Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering Kofman’s feature-length 2002 documentary Derrida, the great philosopher is asked what he would want to see in a documentary about a great philosopher like Kant, Heidegger, or Hegel. After a thoughtful pause that lasts an uncomfortable twelve seconds, Derrida replies, “Their sex lives.” I don’t mean a porno, he clarifies, but to hear them talk about their sex lives would be interesting because it is the thing they refuse to talk about. Why, he asks, turning what is already meta-question around again, do philosophers present their thoughts as though they, the people who think those thoughts, are asexual?

Why, indeed. The film introduces us to Derrida’s wife, Marguerite, but omits any acknowledgment of the affair and son he had with the philosopher Sylviane Agacinski. Meanwhile, despite a volatile and, one would not have to go far out on a limb to say, libidinal teacher-student dynamic between the two men, Derrida never so much as mentions Foucault’s name.

***

After the publication of the first volume of The History of Sexuality in 1976, Foucault did not publish a single-author book until he was on his deathbed in 1984. In those nearly eight years, he taught and researched and changed his mind about what made up the history of sexuality. He addresses the generative quality of this delay in the preface to the second volume, The Use of Pleasure, with an unusual degree of writerly clarity: “to those, in short, for whom to work in the midst of uncertainty and apprehension is tantamount to failure, all I can say is that clearly we are not from the same planet.” I admit I would have to strain to find this moment outright sexy, but I am more than a little attracted to its confidence.

So much of the work that’s associated with these last eight years of Foucault’s life takes the form of seminars and interviews, the latter of which he increasingly granted to the gay press both in France and in the United States. His doing so required a delicate touch, as Foucault clearly wanted to encourage the flourishing of gay expression that the gay press represented, but he also maintained his skepticism about why, among all aspects of what makes up a person, sexuality was so privileged as to appear to tell the truth of one’s self. In a 1981 interview with the recently founded Le gai pied, Foucault pushes the point, responding to an interviewer’s question about whether desire is dependent on age by pivoting away from desire at all. He speaks of homosexuality not as a form of desire or even as a sexual practice but as a social relationship:

One of the concessions one makes to others is not to present homosexuality as anything but a kind of immediate pleasure, of two young men meeting in the street, seducing each other with a look, grabbing each other’s asses and getting each other off in a quarter of an hour. There you have a kind of neat image of homosexuality without any possibility of generating unease, and for two reasons: it responds to a reassuring canon of beauty, and it cancels everything that can be troubling in affection, tenderness, friendship, fidelity, camaraderie, and companionship, things that our rather sanitized society can’t allow a place for without fearing the formation of new alliances and the tying together of unforeseen lines of force. I think that’s what makes homosexuality “disturbing”: the homosexual mode of life, much more than the sexual act itself. To imagine a sexual act that doesn’t conform to law or nature is not what disturbs people. But that individuals are beginning to love one another—there’s the problem.

It’s difficult to put my finger on a story or an example of how consequential these sentences felt, because they were infused almost completely into the ways that my friends and I imagined sexuality. AIDS had given us a sense that the narrative we had inherited about sex was broken, but a framework like Foucault’s helped us to imagine that friendship could be one of the side benefits of sex, rather than the other way around—that sex might exist in new kinds of relations, that it could be the basis of something whose shape we could not yet see. Fatality yielded to possibility, and it made a wonderful addendum that this interview had been translated into English and published with the title “Friendship as a Way of Life.” Some new way of living was exactly what we dreamed of forging out of sex.

However, we were also reading in the ways our desires pulled. To be sure, if Foucault was generative in his account of sexuality as sociability, he was nonetheless critical of sexuality as individual psychology and identity. We followed him one way more than the other. I’m certain that it felt important to my friends and classmates in college that we had the chance to be ourselves, and the idiom of sexuality—desire, fantasy, and the specification of identity—was undoubtedly something that, to us, felt true, in all the ways that Foucault critiques. Coming out as gay (or bi or queer or whatever else) was a potent political idiom in the Nineties, one that had arguably gained more clout in the ten years after Foucault’s death than in the ten before.

The saving grace of the situation, however, was that the conversation did not end there. Really, it barely began there. Coming out seemed to us to be the springboard not for finding ourselves but for finding one another. It was a one-way ticket to getting to make up a social world however you might want it to look: creating history but also creating a present and future. There could be affection, tenderness, friendship, fidelity, camaraderie, and companionship, and these things could be coextensive with sex or not. Whether you were lovers with someone was something we learned to value but also to place on a spectrum with other dimensions of friendship. These ideas inflated to the lofty status of an ethic. We wanted to have sex, and we wanted to have a way of life; and we relished the support that theory lent to the idea that these wants overlapped significantly. Sex grew intelligible with theory, and from that vantage theory looked pretty sexy.

Take gay marriage, for example. Already in the mid-1990s the issue was being debated at the state level, including high-profile cases in Hawaii and Massachusetts. But these had for us little of the aura of a meaningful civil rights issue. We young people in our queer relationships imagined instead that we were engaged in forms of social attachment that were genuinely alternative to marriage, that, indeed, might be better than marriage, and that in any case deserved to be tested out.

Test takers abounded. I knew people who were polyamorous, with multiple serious partners at once, or people who only dated couples, effectively having a relationship with other people’s relationships. I met people who were best friends and sometimes even roommates with their exes—a testament to the ways that connections endure even if romance doesn’t work out. I knew other people in fairly conventional, monogamous partnerships who nonetheless cohabitated well into adulthood with other individuals or couples—chosen family—and shared meals and bills and raised children and, sometimes, buried one another. All of these were attempts to test how life might be lived, various schemes for mapping affection and attachment and responsibility otherwise than in the normative monogamous, couple-based pattern that, to many of us who’d grown up in a world of women wage earners and no-fault divorce, looked fairly arbitrary. By comparison, gay marriage seemed like a retrograde position.

Amid all this experimentation, perhaps the story that best illustrates the reach of “Friendship as a Way of Life” into the ethos of my youth is the one in which, in about 2010, a decade after college and well into my first teaching job, I sat down to reread the interview and was shocked to discovered that I’d never read it before. Parts of it were completely familiar, and I must have encountered them in excerpt or citation. But most of it was just brand new. Meanwhile, nowhere among my books or papers was there even a copy of the interview to be found. When I Googled further, it became clear that the interview had been published only in books I was quite sure I’d never owned. Though I had memories and impressions of “Friendship as a Way of Life,” I had no distinct memory of reading it. All the same, it felt consistent with the spirit of the piece to imagine that I’d put the practice of making a life ahead of reading the theory.

***

Foucault theorized sexuality, but he also lived it out. This duality was confirmed in conjunction with his early visits to Berkeley in 1975 and again in 1979 and after. One consequence—let’s call it the theoretical or at least professional one—was that two Berkeley professors, Hubert Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow, began to collaborate with Foucault on an authoritative primer to his thought, eventually published as Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics (1982); but another consequence—let’s call it the living or perhaps personal one—was that a Claremont College professor, Simeon Wade, and his lover, Michael Stoneman, invited Foucault to join them for an LSD trip in Death Valley, involving as well an interview, which Wade self-published as part of a zine called Chez Foucault in 1978, and an account of the LSD trip, Michel Foucault in Death Valley, published only in 2019, that a number of Foucault scholars and biographers have worked hard to track down.

According to the kind of academic perspective from which theory is usually studied, it’s easy enough to imagine that the work with Dreyfus and Rabinow is Foucault’s real work and that his time with Wade and Stoneman was a diversion. The mechanisms of academic knowledge transmission (what gets recorded, what gets published, what qualifies a person for tenure) would seem to reinforce the point—as, by the way, do Foucault’s biographers (and if you don’t believe me, check which proper names get indexed). But such a point pulls as much against Foucault’s corpus of thought as it does away from the facts of his biography. There is absolutely no indication that Foucault, the guy who once argued that Nietzsche’s grocery list might properly be included among Nietzsche’s complete works, would posit any meaningful difference between the professional collaborations of the mind and the improvisational collaborations of the flesh.

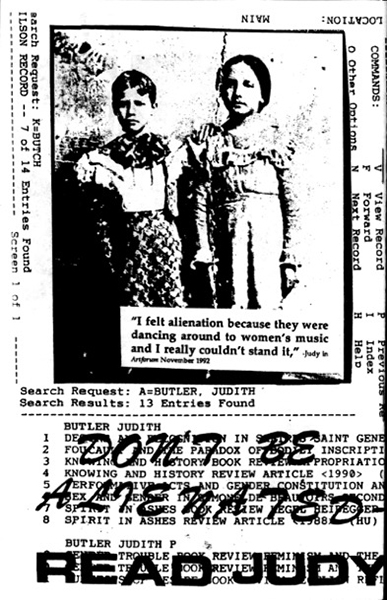

In the same spirit, fifteen years after Wade’s Foucault zine, in 1993, Andrea Lawlor anonymously published a fanzine called Judy! It presents a loving, irreverent, and unmistakably erotic tribute to Judith Butler, author of the foundational (and then quite recent) theoretical tomes Gender Trouble (1990) and Bodies That Matter (1993). Lawlor was a college student in Iowa at the time, and the zine tells of a pilgrimage to an MLA conference in New York City, where she met or hoped to meet Butler (the zine is elliptical on the juicier details). Unable to find many pictures of Butler in those pre-Google days, she festooned the zine with other Judys, most prominently Judy Garland, as well as with cheeky and out-of-context references to Butlerian concepts like the lesbian phallus (which, isolated from the complicated theoretical armature that Butler’s chapter on this topic elaborates, sounds undeniably like a sex toy—a really hot sex toy). Coordinating the work of the mind and the work of the body were part of Butler’s project, as they had been for Foucault, as it seems they were for Wade and Lawlor in turn. In all these cases, as most certainly in my own, reading theory involved the dual experience of reading about gender and sexuality, on the one hand, and trying to navigate the fact of having a gender and a sexuality, on the other.

The broader project of trying to relate these theories and practices in the Nineties blossomed under the sign of “queer theory.” Many of its practitioners were literature scholars, lots of whom were the products of elite graduate programs but who had also earned their stripes in the women’s movement, in AIDS activism, and/or in antiracist political organizing. After about 1991, their common project came to be called queer theory, though the phrase is noticeably absent from books by Foucault, Butler, or Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick that are often taken as foundational to the movement. Queer theory looked most often in those early days like an offshoot of radical feminism that wanted to proceed from a critique of the idea that sex and gender had any basis in nature (that sex itself and not just gender was, in the resident vernacular, “socially constructed”). Queer theorists, then, were people who knew something about the relationship between theory and practice, and queer theory became a kind of road map for those of us who wanted to better understand their relationship.

I don’t mean to make queer theory sound as though its project were entirely coterminous with that of, say, self-help literature. But I would insist that queer theory was trying to think about the cultural, political, and personal meanings of sex at a moment in the Nineties when those meanings were more up for grabs than they had been in at least a generation. Whether queer theory was a cause or effect of that historical epoch, I cannot finally say. (I mean: both.) Nevertheless, something about that moment meant that queer theory’s work of sorting out what sex means and the more broad-based work among theorists of relating the mind to the body felt very obviously like related tasks.

For example, one of most enduringly generative theory texts of the Nineties remains Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet (1990), and among its many excellent concepts is “gender transitivity.” Against the idea that one’s biological sex (let’s say, male) would line up with one’s gender presentation (masculine) and one’s fantasy life (dominant) and one’s preferred sexual object (women)—a view she summarized as “gender separatist” but what we might now call “hetero-” or “cis-normative”—Sedgwick theorized that a person might experience all kinds of misalignments in this scheme. Homosexuality, in which the gender of one’s preferred sexual object is not normatively optimized with other components of identity, was, for her, just one of many complications. An intriguing consequence of this scheme was that a person might have a gender and a preferred sexual object that all lined up with her or his biological sex while nonetheless maintaining a fantasy life that veered elsewhere. That possibility was a queerness, just as much as any more observable social behavior like homoerotic sex or gender nonconformity.

The excitement of such a possibility had to do with the implication that queerness wasn’t just a matter of sexual identity in the usual sense. Gender transitivity could happen at the level of fantasy, and fantasies could get acted out or not. Queer theory in this vein did a lot to validate the possibility that you might desire the idea of something you didn’t actually want to do or that you might identify with people who were not in some observable ways “like” you. Queer theory dignified the prospect that you could see yourself as someone at variance from what other people see about you. At the same time, those possibilities didn’t make you a particular kind of person, not an x or a type or kind, unless perhaps you wanted to be. “Queer” held open the space of something astonishingly variable and open-ended. All you had to be was yourself, in all your myriad social, psychological, and performative complexity.

Accordingly, I recall a large number of conversations in those years with people who were functionally speaking gay men—assigned male at birth, chose other men as their preferred sexual objects—who identified heavily with lesbians. Playful, sometimes flirtatious affinities between gay men and lesbians all landed along the spectrum of “queer,” though whether those landings properly snapped identity into place or into flux depended on other variables like your community, its politics, its average age.

But again I don’t mean to make queer theory sound purely intellectual. The summer I read Epistemology of the Closet I did so mostly on the bus, commuting between the beautiful campus up on a tree-covered hill where I worked and the dumpy condo down by the low-rent beach in the unincorporated part of town where I lived. I’d fill my head with Sedgwick’s abstract ideas about how the hetero/homo dichotomy was central to knowledge production in the modern West more generally and then get home, change into my running shoes, and think it through as I ran along the road by the beach. One day my running path veered closer to the beach parking lot, where I saw a pair of muscly surfers stripping off their wet suits in the showers. Suddenly few things in the world seemed to have the complexity of a dichotomy. I ran on, aroused and embarrassed by the body’s intrusion into the contemplation of the mind. It honestly did not occur to me that I might have asked those guys to join my reading group.

***

Part of all this interest in transitivity had to do with the fact that so much of sex in the Nineties was consigned to the realm of fantasy. In a 1982 interview, later published in the Advocate, Foucault gets asked what he thinks about the proliferation of “male homosexual practices” in the past ten years: “porn movies, clubs for S&M or fistfucking, and so forth.” Once again steering the conversation away from the idea that desire is innate, Foucault replies that it’s not that people always wanted to participate in S/M scenes so much as that the availability of those scenes becomes a place where people can learn and desire in new ways. Foucault highlights the creativity and sense of possibility—social and subjective possibilities, new ways of being—that the proliferation of sexual practices ushers in.

But, I mean, how exciting was it to talk about fistfucking?! It’s not like any of us were into it. It’s not like any of us knew anyone who was. Even in the undergraduate demimonde of off-campus housing, few people I knew were having sex with as much regularity as they might have liked, let alone experimenting with the so-called recent proliferation of male homosexual practices. But it was still exciting to talk about it, to outline in theory something that might not otherwise assume a shape either in practice or in fantasy. It was certainly gratifying to imagine that fistfucking had enough conceptual integrity to show up in a theoretical conversation alongside more traditional philosophical concepts like desire or personhood. We debated the desire of things we didn’t specifically desire for ourselves. Theory became a site, like porn or sex clubs, to learn about sex, even if that learning confined itself to abstraction.

Even if—but maybe also especially. The draw of queer theories like Foucault’s or Sedgwick’s had something to do with the opportunity for talking about sex and desire—for giving airtime to those things that AIDS and youth conspired to make us feel were so embarrassing—while still keeping the conversation intellectual, hypothetical. Desire became an idea to be debated and discussed, not, or not just, a personal feeling to be displayed in all our hesitancy and inexperience. I talked about sex in academic fora and essays and classrooms, as a theoretical thing, all the time after about age nineteen. But I was well into my thirties before I ever alluded, even elliptically, to my actual, personal sex life in any public or professional context. The former felt enabling, expansive; the latter continued to be tinged by shame long after my own experiences with sex stopped being hypothetical.

From what I can gather, my students today learn about sex from the abundance of internet porn. They will have watched people have sex many times before they attempt any of those same actions themselves. Porn is their sex education, and if they are curious about fistfucking, without much difficulty they can find videos, Q&As, even tutorials. For my friends and me in our youth, fistfucking was much more an idea, and we loved it as one. But those were the Nineties, when things that were outré became comprehensible without exactly being real, when history drove a wedge between desire and its fulfillment, which theory then helped us to bridge.

***

The summer after college, I fell in love. One night, my paramour came over, and we fucked until the early hours of the morning. Then, somehow, holding each other in the sweat-soaked sheets, we got into an argument about the theory of disciplinary power that Foucault outlines in the first volume of The History of Sexuality. The argument lasted twice as long as the sex did. I liked this ratio, and this juxtaposition, of the life of the mind and the life of the body. I looked at this boy in the dark and thought, “This could work.” For a while, it really did.

Kristeva, Desire in Language (Columbia University Press, 1980)