CHAPTER TWO

A Buyer’s Guide to Goats

Don’t rush out to buy some goats. It’s a bad idea when purchasing any type of livestock but especially risky when getting into goats. Though goats aren’t hothouse flowers, neither are they the happy-go-lucky, can-noshing species of movies and cartoons. Goats require specialized handling and feeding—and keeping goats contained in fences is never a lark. Goats are cute, personable, charming, and imminently entertaining. They can be profitable, particularly in a hobby farm setting. But goats are also destructive (picture a four-legged, cloven-hoofed, tap dancer auditioning on the hood of your truck), mischievous, sometimes ornery, and often exasperating. Be certain you know what you’re getting into before you commit.

Find yourself a mentor. Most experienced goat producers are happy to teach new owners the ropes. To track down a mentor, ask your county extension agent for the names of owners in your locale, join a state or regional goat club, or subscribe to goat-oriented magazines and e-mail groups to find goat-savvy folks in your area. A mentor or extension agent can talk with you about which breed will meet your needs and what to look for when buying your goats and what happens once you do. You need to educate yourself as well. Here are the issues you should consider and the basic information you should have on goat-buying transactions.

CHOOSING THE BREEDS

Before going goat shopping, know precisely what you want. Make a list of the qualities you’re looking for, star the ones you feel are essential, and note which ones you’re willing to forgo. Some breeds fare better than others in certain climates. Certain breeds are flighty. Some make dandy cart goats, whereas others are too small for harness work unless you plan to drive a team. If you want a goat who milks a gallon a day, a Pygmy doe won’t do. However, if you’re looking for a nice caprine friend and you don’t want to make cheese or yogurt, a Pygmy doe (or two) could prove the perfect choice. (See box “Common Goat Breeds in Brief.”) Consider availability as well in your choice—whether you’re willing to go farther afield to get exactly the breed you want.

PUREBRED, EXPERIMENTAL, GRADE, OR AMERICAN?

Registered goats generally cost more to buy than do grade (unregistered) goats, but you might not need to spring for registered stock. It depends on your goals. If you plan to exhibit your animals at high-profile shows, or to sell breeding stock to other people, you probably do. If you want a pack wether, a 4-H show goat, or a nice doe to provide household dairy products, registration papers aren’t essential.

A registration certificate is an official document proving that the animal in question is duly recorded in the herdbook of an appropriate registry association. Depending on which registry issues the certificate, the document will provide a host of pertinent details, including the goat’s registered name and identification specifics—such as its birth date, its breeder, its current and former owners, and its pedigree. Dairy breed papers also document milk production records in great detail. You can contact the ADGA with any questions you may have about the latter.

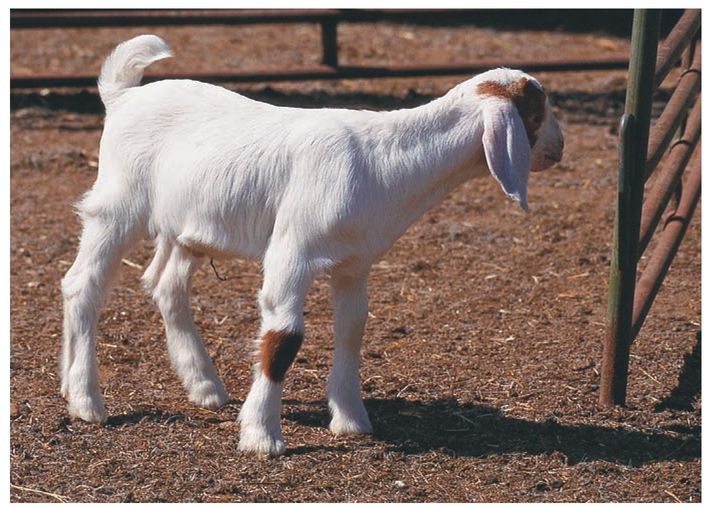

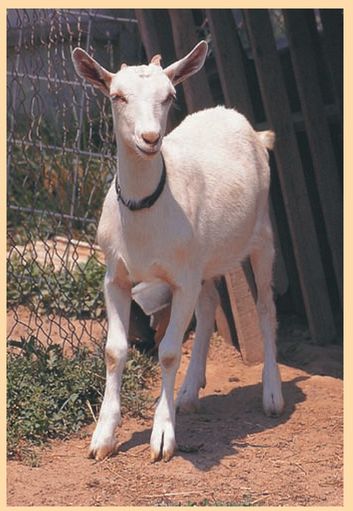

Wee baby Salem, just three weeks old, is three-fourths Boer and one-fourth Nubian, a popular type of percentage Boer goat. His famous sire is the MAC Goats champion buck Hoss.

The four categories of dairy goats in terms of registration are purebred, experimental, grade, and Americans. Purebreds are registered goats that come from registered parents of the same breed and have no unknowns in their pedigrees. Experimentals are registered goats that come from registered parents but of two different breeds. A goat of unknown ancestry is considered a grade. However, several generations of breeding grade does to ADGA-registered bucks (always of the same breed) and listing the offspring with ADGA as recorded grades eventually results in fully registerable American offspring. For example, seven-eighths Alpine and oneeighth grade doe is an American Alpine; a fifteen-sixteenths Nubian and onesixteenth grade buck is an American Nubian. However, ADGA terminology doesn’t apply to meat goats.

To qualify as a registered full-blood in the American Boer Goat Association herdbook, all of a goat’s ancestors must be full-blood Boer goats. Registered percentage does are 50 to 88 percent full-blood Boer genetics; percentage bucks are 50 to 95 percent Boer. Beyond that (94 percent for does, 97 percent for bucks), they become purebred Boers. Purebreds never achieve full-blood status.

The International Kiko Goat Association registers New Zealand full-bloods (from 100 percent imported New Zealand bloodlines), American premier full-bloods (of 99.44 percent or greater New Zealand genetics), purebreds (87.5 to 99.44 percent New Zealand genetics), and percentages (50 and 75 percent New Zealand Kiko genetics). To avoid making costly mistakes, learn your breed’s registration lingo before you buy!

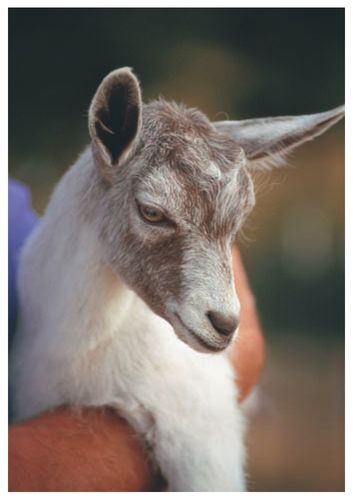

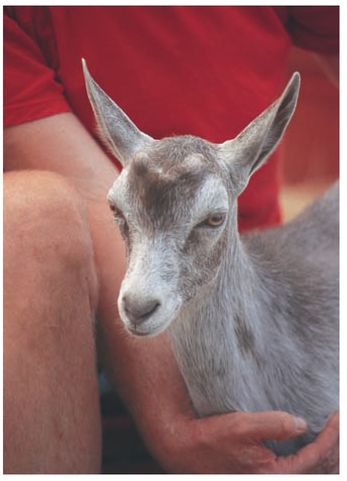

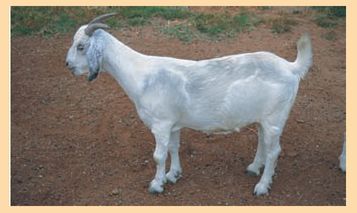

This is Morgan, our sweet Sable baby bred by Christie’s Caprines. Saanens have occasionally produced colored offspring, called Sables, which recently have come to be recognized as a separate breed.

Pets, cart and pack goats, brush clearers, and low-production household dairy goats needn’t be of any specific breed. Mixed-blood goats cost less to buy and no more to maintain than fancy registered stock and may be precisely the animals you need.

AVAILABILITY

If you’re seeking Nubians, Pygmies, or Boers, you’ll probably find a plentiful supply of good ones close to home. Less common breeds, such as Sables, Kinder goats, and colored Angoras, may be a different story. If you don’t want to travel long distances to buy foundation or replacement stock, pick a common breed or at least one popular in your locale. Conversely, though it takes more effort to start with something out of the ordinary, it also assures a market for your goats—other seekers don’t want to range afar, either.

Goat auctions and buying stations such as this one are marketing mainstays for commercial meat goat producers.

Purchasing goats from a distance has its pitfalls because you may not be able to visit the sellers and inspect potential purchases in person. If this is the case, buy only from breeders whose sterling reputations (and guarantees) take some of the gamble out of longdistance transactions. The transportation of distant purchases is also an issue, but it needn’t be a major one. Livestock haulers and some horse transporters carry goats cross-country for a fee. Kids and smaller goats can be inexpensively and safely shipped by air.

If you’re buying close to home, you can locate breeders via classified ads (free-distribution classifieds are especially rich picking), through notices on bulletin boards (watch for them at the vet’s office and feed stores), and by word of mouth (your county extension agent or vet can usually put you in touch with local goat owners). Or place “want to buy” ads and notices of your own.

To get a feel for breeders and to learn what sort of goats they have for sale, visit breed association Web sites or subscribe to print and online goat periodicals. Peruse the ads and breeders directories, and sign up for goat-oriented e-mail groups.

Goats auctioned through upscale production sales and consignment sales hosted by bona fide goat organizations are generally the cream of the caprine crop. Never buy goats at generic livestock sale barns. Run-of-the-mill livestock auctions are the goat farmer’s dumping ground. Most animals run through these sales are culls or sick, and the ones who aren’t will be stressed and exposed to disease. A single livestock sale bargain can bring nasties the likes of foot rot, sore mouth, and caseous lymphadenitis (CL) home to roost, sometimes to the tune of thousands of dollars in vet bills and losses. Buy your goats through high-profile goat auctions or from private individuals.

SELECTING THE GOATS

The cardinal rule when buying goats: start with good ones. Choose the best and the healthiest foundation stock you can afford.

CONFORMATION

Acceptable conformation—defined as the way an animal is put together—varies among dairy, meat, and fiber goats. It’s important to study a copy of your breed’s standard of excellence, available from whichever registry issues its registration papers, before you buy. Don’t discount the importance of good conformation; you’ll pay more for a correct foundation goat, but he’s worth it. Even if you never show your goats, buyers will pay higher prices for your stock.

HEALTH

Never knowingly buy a sick goat! Carefully evaluate potential purchases before bringing them home. A healthy goat is alert. He’s sociable; even semiwild goats show interest in new faces. A goat standing off by himself, head down, disinterested in what’s going on is probably sick or soon will be.

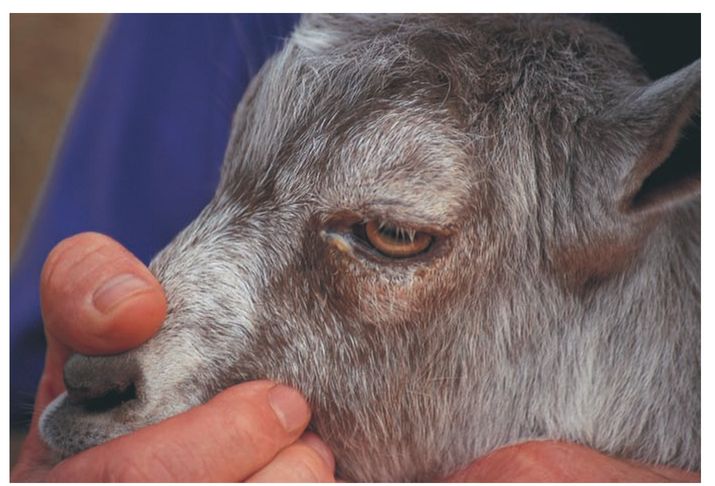

The discharge from Morgan’s eyes suggests early stages of pinkeye. When buying, beware of goats with runny eyes; there could be a serious health issue. Fortunately, Morgan’s problem was simply dust irritation and was easily treated with saline solution and antibiotic eye ointment.

A healthy goat is neither tubby nor scrawny. He shows interest in food if it’s offered, and when resting, he chews his cud. His skin is soft and supple; his coat is shiny. His eyes are bright and clear. Runny eyes and a snotty nose are red flags, as are wheezing, coughing, and diarrhea (a healthy goat’s droppings are dry and firm). Unexplained lumps, stiff joints, swellings, and bare patches in the coat spell trouble. Avoid a limping goat; he could have foot rot (or worse).

If in doubt and you really want a particular animal, ask the seller if you can hire a vet to take a look, and consider it money well spent.

Morgan is a polled Sable, meaning he was born without horn buds. The lumps on his forehead show where his horns would have been.

HORNS

If you don’t like horned goats, don’t buy a goat that has them; you can’t simply saw them off. The cores inside a goat’s horns are rich in nerves and blood vessels. Dehorning, even done by a veterinarian and under anesthesia, is a grisly, dangerous, and ultimately painful procedure that leaves gaping holes in an animal’s skull. With dedicated follow-up care these holes will eventually close, but why expose an animal to this kind of torment?

Dairy goat kids are routinely disbudded when they’re a few days to a week or so old. This is accomplished by destroying a kid’s emerging horn buds, burning them with a disbudding iron. Though it’s painful and not a procedure best performed by beginning goat keepers, disbudding is far more humane than exposing a goat to full-scale dehorning later on.

Meat and fiber goat producers and recreational goat owners are far less likely to eschew horns, but all goats exhibited in 4-H shows—even the ones that are shown in 4-H meat goat, fiber goat, driving, and packing classes—must be hornless or shown with blunted horns.

Should horns be a problem? It depends. You probably don’t want them if you confine your goats (they’ll butt one another, probably causing injuries); if they’ll be expected to use stanchions or milking stands; if you have small children who might get poked, or if you’d prefer not to be poked yourself; if your other goats are polled (naturally hornless) or disbudded. However, science theorizes that horns act as thermal cooling devices, so if you have working pack or harness goats or you live where it’s hot, they’re a boon.

TEETH

A goat has front teeth only in the lower jaw. In lieu of upper incisors, there is a tough, hard pad of tissue called a dental palate. For maximum browsing efficiency, the lower incisors must align with the leading edge of the dental palate, neither protruding beyond it (a condition called monkey mouth or sow mouth) nor meeting appreciatively behind the dental palate’s forward edge (parrot mouth).

Beginning at about age five, a goat’s permanent teeth begin to spread wider apart at the gum line, then break off, and eventually fall out. A goat with missing teeth is said to be broken-mouthed. When his last tooth is shed (around age ten), he’s a gummer. Aged goats with broken teeth have difficulty browsing, so unless you’re willing to feed soft hay or concentrates, check those teeth before you buy.

SEX-SPECIFIC FACTORS

No matter what class of stock you raise—be they dairy, meat, or fiber goats—buy does with good udders. A goat’s udder should be soft, wide, and round, with good attachments front and rear. The two sides should be symmetrical. Avoid lopsided, pendulous udders with enormous sausage teats, especially in dairy goats, and reject goats with extremely hot, hard, or lumpy udders—these being telltale signs of mastitis involvement.

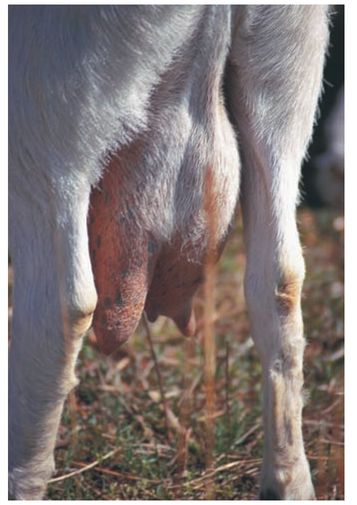

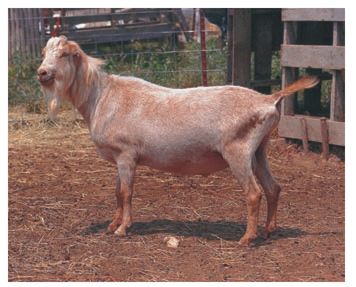

Note the enlarged left teat of this goat. Lopsided udders are undesirable.

Dairy goats should have two functioning teats with one orifice apiece. Deviations from the norm are serious faults and are rare. Dairy kids are sometimes born with additional vestigial teats, but they’re usually removed when doelings are disbudded.

Meat goats, especially Boers, are often graced with more than two teats. In Boers, up to two adequately spaced, functional teats per side are acceptable. However, nubs (small, knoblike lumps that lack orifices), fishtail teats (two teats with a single stem), antler teats (a single teat with several branches), clusters (several small teats bunched together), and kalbas or gourd teats (larger roundish lumps that have orifices) frequently occur. A blind teat (one lacking an orifice) can be dangerous if newborns consistently suckle on it in lieu of a functional one; the kids will literally starve. Most of these irregularities disqualify a doe from showing.

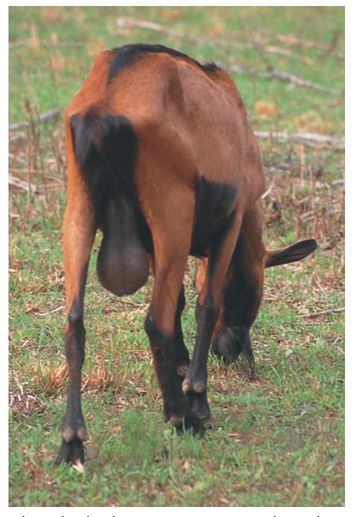

This Oberhasli’s scrotum is just right. When buying a buck, size counts; large testicles equate with fertility and breeding vigor.

Male goats have tiny teats, too; they’re situated just in front of the scrotum on a buck. Although they aren’t important in and of themselves, check for the same irregularities in breeding bucks as you would in does. Bucks with unacceptable teat structure may sire daughters with bad udders. Bucks with more than two separated teats per side generally can’t be shown.

Bucks must have two large, symmetrical testicles. When palpated, the testicles should feel smooth, resilient, and free of lumps. An excessive split separating the testicles at the apex of the scrotum (more than an inch in most breeds) is unacceptable. When choosing a buck, size matters. The greater his scrotal circumference, the higher his libido and the more semen he’ll likely produce. A mature buck of most full-size breeds should tape 10 inches or more, measured around the widest part of his scrotum. Boer bucks must tape at least 11.5 inches (American Boer Goat Association) or 12 inches (International Boer Goat Association) by maturity at two years of age.

When buying a wether, ask when the goat was castrated. Since castration abruptly halts the development of a young male’s urinary tract and affects adult penis size, early castration predisposes male goats to water belly, also known as urinary calculi. In this condition, mineral crystals in his urine block his underdeveloped urethra and cause his bladder to burst; death occurs within a few days. Castration of pet and recreational goats is best postponed until the animal is at least one month old (later is better).

Whichever sex you’re considering, be aware of one of the peculiarities of goat breeding: breeding polled goats to one another sometimes results in her-maphrodite offspring (displaying both male and female sexual organs). It pays to check, keeping in mind that male goats always have teats, so you don’t end up with one these unusual goats.

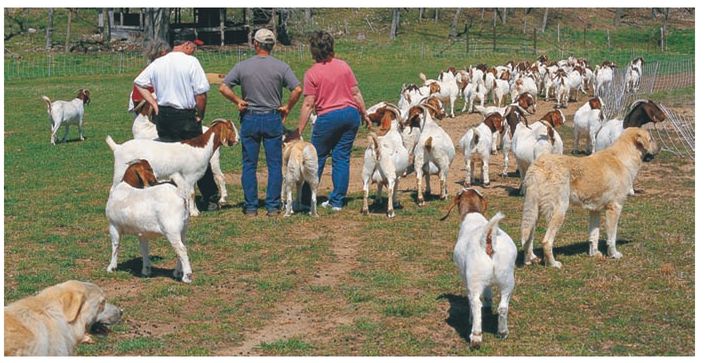

Matt Gurn shows a field of friendly MAC Goats Boers to visiting buyers. Goats are curious; these crowd around to see what’s going on.

THE SALE

You’ve done your homework, and you’re ready to buy. Based on your research, contact sellers who produce the sort of goats you want. Make appointments to visit and view their animals. Goat producers and goat dairy farmers are busy folks, so keep your appointments or call to cancel. It never hurts to ask for a seller’s references in advance, especially when buying expensive goats. Be sure to check them out before your visit.

When you arrive, look around. Though fancy facilities are never a must, goats should be kept in clean, safe, comfor table surroundings. Do the goats appear healthy? Are they friendly? Are their hooves neatly trimmed? Their drinking water clean, their feeders free of droppings? Evaluate the seller, too. Does he or she seem knowledgeable, honest, and sincere?

Ask to see prospective purchases’ health, worming, and breeding production records (and milk production records for dairy goats). Virtually all responsible goat breeders and dairy operators keep meticulous records. If the seller can’t produce them, be suspicious.

Carefully inspect paperwork when buying registered goats. Have registration certificates been transferred into the seller’s name? (He can’t legally transfer them into your ownership unless he’s the certified owner of record.) Does the description on the papers match the goat? Check ID numbers tattooed inside ears (and sometimes the underside of their tails) against numbers printed on registration papers, ditto numbers embossed on any ear tags. Sometimes a seller has “misplaced the papers” and will “mail them to you when they turn up.” Don’t buy the story. Without an up-to-date registration certificate in your hand, you’re paying registered price for a goat that may be grade.

Common Goat Breeds in Brief

Here’s a brief look at the different breeds of goats you can choose from depending on whether you want dairy, fiber, or meat goats, or pets.

Dairy Goats

Alpine (also called French Alpine)

Alpine goats originated in the French Alps. They are medium to large goats—does at least 30 inches tall and 135 pounds, and bucks 34 inches and 170 pounds. Friendly, inquisitive Alpines come in a range of colors and shadings. Because of their productivity and good natures, Alpines are popular in commercial dairy settings.

LaMancha

The almost-earless LaMancha (at least 28 inches and 130 pounds) is an all-American goat developed in Oregon during the 1930s. Goat fanciers claim LaManchas are the friendliest of the dairy goat breeds. They can be any color. Two types of ears occur among them: gopher (1 inch or less in length, with little or no cartilage) and elf (2 inches or less in length, with cartilage). LaManchas produce copious amounts of high-butterfat milk.

Miniature Dairy Goats

The Miniature Dairy Goat Association registers scaled-down (20–25 inches tall, weight varies by breed) versions of all standard dairy goat breeds, among them Mini-Alpines, Mini-LaManchas (MiniManchas), Mini-Nubians, Mini-Oberhaslis, Mini-Saanens, and Mini-Toggenburgs. Miniatures have the same standards of perfection as those of full-size counterpart breeds.

Nigerian Dwarf

Nigerian Dwarfs are perfectly proportioned miniature dairy goats, capable of milking three to four pounds of 6–10 percent butterfat per day. Gentle, personable Nigerians can be any color. They breed year-round; multiple births are common. (Four per litter is the average; though there have been births of as many as seven.) Does are typically 17–19 inches tall, bucks 19–20 inches; 75 pounds for both sexes.

Nubian (also called Anglo-Nubian)

Nubians were developed in nineteenth-century England by crossing British does with bucks of African and Indian origins. A noisy, active, medium- to largesize dairy goat (does at least 30 inches and 135 pounds, bucks 35 inches and 175 pounds), Nubians are known for their high-butterfat milk production, sturdy build, long floppy ears, and aristocratic Roman-nosed faces. All colors and patterns are equally valued.

Oberhasli

Alert and active, Swiss Oberhaslis are medium-size goats (minimum for does is 28 inches and 120 pounds, for bucks 30 inches and 150 pounds). They are always light to reddish brown accented with two black stripes down the face, a black muzzle, a black dorsal stripe from forehead to tail, a black belly and udder, and black legs below the knees and hocks.

Saanen

These big (30–35 inches and 130–170 pounds) solid white, pink-skinned dairy goats from Switzerland are friendly, outgoing heavy milkers, with long lactations. They are popular commercial dairy goats, often called “the Holsteins of the goat world.”

Sable

Sables are colored Saanens, newly recognized as a separate breed. Because their skin is pigmented, they don’t sun burn as Saanens sometimes do.

Toggenburg

Toggs are smaller than the other Swiss dairy breeds. They are some shade of brown with white markings (white ears with a dark spot in middle of each, two white stripes down the face, hind legs white from hocks to hooves, forelegs white from knees down).

Fiber Goats

Angora

The quintessential fiber goats, Angoras produce long, silky, white or colored mohair. Angoras are medium-size goats (does are 70–110 pounds, bucks 180–225; height varies). They aren’t as hardy as most other breeds. Twinning is relatively uncommon. Angoras must be shorn at least once a year.

Cashmere

Cashmere goats are a type, not a breed. Goats of all breeds, except Angoras (and one class of Pygoras), produce cashmere undercoats in varied quantities and qualities. High-quality, volume producers are considered cashmere goats.

Pygora

Pygoras were developed by crossing registered Angora and Pygmy goats. They’re small (does at least 18 inches tall and 65–75 pounds; bucks and wethers at least 23 inches tall and 75–95 pounds), easygoing, and friendly, and they come in many colors. Some

Common Goat Breeds in Brief

Pygoras produce mohair, some cashmere, and others a combination.

Meat Goats

Boer

The word boer means “farmer” in South Africa, land of the Boer goat’s birth. Big (does weigh 200–225 pounds and bucks 240–300 pounds; height can vary greatly), flop-eared, Roman-nosed, and wrinkled, the Boer is America’s favorite meat goat. Boers are prolific, normally producing two to four kids per kidding, and they breed out of season, making three kiddings in two years possible. Boer colors include traditional (white with red head), black traditional (white with black head), paint (spotted), red, and black.

GeneMaster

GeneMaster goats are three-eighths Kiko and five-eighths Boer goats developed by New Zealand’s Goatex Group company, the folks who pioneered the Kiko goat. Pedigree International currently maintains the North American GeneMaster herdbook.

Kalahari Red

Kalahari Reds look like large, dark red Boers. Kalahari Reds are a developing breed in South Africa. Though a few American producers are breeding true South African stock, most North American “Kalahari Reds” are simply solid red Boers.

Kiko

Kiko means “meat” in Maori. Kikos were developed in New Zealand by the Goatex Group. Beginning with feral goat stock, breeders selected for meatiness, survivability, parasite resistance, and foraging ability and, in doing so, created today’s ultrahardy Kiko goat.

Myotonic

Today’s Myotonic goats (also called fainting goats, fainters, wooden legs, Tennessee Peg Legs, and nervous goats) are believed to be the descendants of a group of Myotonic goats brought to Tennessee around 1880. When these goats are frightened, a genetic fluke causes their muscles to temporarily seize up; if they’re off balance when this happens, they fall down. Myotonic goats come in all sizes and colors (black and white is especially common). They don’t jump well, so they’re easy to contain; and they’re noted for their sunny dispositions.

Savanna

Big, white, and wrinkled, South African Savanna goats resemble their Boer cousins, but with a twist. South African Savanna breeders used indigenous white goat foundation stock and natural selection to create a hardierthan-Boers breed of heat-tolerant, drought-and-parasite-resistant, extremely fertile meat goats with short, all-white hair and black skin. Savannas’ thick, pliable skin yields an important secondary cash crop: their pelts are favorites in the leather trade. Fewer than a score of North American breeders offer full-blood Savanna breeding stock, but interest in the breed is skyrocketing. Pedigree International maintains the official Savanna herdbook.

Spanish

Spanish goat is a catchall term for brush goats of unknown ancestry, so no breed standard exists. Spanish goats can be any color, although solid white is most common; both sexes have huge, outspreading horns.

Tennessee Meat Goat

Suzanne W. Gasparotto of Onion Creek Ranch developed the spectacular Tennessee Meat Goat by selectively breeding full-blood Myotonic goats for muscle mass and size. Pedigree International maintains the Tennessee Meat Goat registry.

TexMaster Meat Goat

The TexMaster Meat Goat, another Onion Creek Ranch development, was originally engineered by crossing Myotonic and Tennessee Meat Goat bucks with full-blood and percentage Boer does (meaning they are a only certain percent Boer, not 100 percent). Pedigree International keeps its herdbook as well.

Other Breeds

Kinder

The Kinder goat (does 20–26 inches, bucks 28 inches; weight varies) is a dual-purpose milk and meat breed developed by crossing Nubian does with Pygmy goat bucks. Prolific (most does produce three to five kids per litter) and easygoing, Kinders make ideal hobby farm milk goats and pets.

Pygmy

Nowadays, Pygmy goats (does are 16–22 inches, bucks 16–23; weight varies) are usually kept as pets, but they developed in West Africa as dual-purpose meat and milk goats. Pygmies are short, squat, and sweet natured. Lactating does give up to two quarts of rich, high-butterfat milk per day, making Pygmies respectable small-family milk goats.

ALBC Conservation Priority List Breeds

The American Livestock Breed Conservancy (ALBC) includes six goat breeds on its Conservation Priority List. Two require immediate help: the critically endangered San Clemente of relatively pure Spanish stock, and the threatened Tennessee Fainting (also called the Myotonic goat or fainting goat). Listed also: Spanish (under the Watch category), Nigerian Dwarf and Oberhasli (Recovering), and another distinctly American product, the scarce, island-bred Arapaw goat (Study). (See the Resources section for ALBC contact information.)

Advice from the Farm

Let the Buyer Beware

Our experts share tips about goat buying.

Hit the Books

“Get some books on goat health. These are great references. They will scare you because they’ll list everything that can go wrong. But until you’ve been raising goats for thirty or forty years, you won’t see even half of those things and even then, you’ll still be learning things about goats.”

—Rikke D. Giles

Beware the Bargains

“Before you get a goat, read all you can about goats and talk to people who have them. Start with an older doe or wether and then get a kid. And don’t buy goats at sale barns. Animals are usually sold at auction for a reason. Sometimes you can get a decent animal if you know what you’re looking for, you know the people who consigned the animal, and you’re lucky. The people that own the sale barn near me do not like goats, so they’re all put into the same pen: bucks, does (very pregnant or dry), little kids, big goats, and little goats—then they’re exposed to all sorts of diseases (pinkeye, snotty noses, abscesses, and so on). If you do buy a goat at a sale barn, don’t put it with your others until it’s been in quarantine for at least two weeks.”

—Pat Smith

Don’t Take Any Lumps

“Although I raise five breeds of pet and show goats and two of sheep, I look for many of the same qualities I’d look for if I were buying meat or dairy goats. I want healthy goats. I look for clear eyes, moist noses, shining coats, strong straight backs with level toplines. I also look for strong, straight legs that don’t have spun hocks or knobby knees. Seeing an animal run helps assure me it has healthy legs. I look at goats’ berries to see if their color and formation show good internal health. I’m also looking for lumps, abscess, crooked jaws, herni- ated navels, or cleft palates.”

—Bobbie Milsom

Go for the Goat!

“I have a milk cow and milk goats. You only need two goats for them to be happy and content, and you can keep seven head of goats per one cow. Plus, goats are more intelligent, friendlier, and safer.”

—Samantha Kennedy

Did You Know?

According to United Nations statistics, the world’s goat population grew from 281 million in 1950 to 768 million in 2003. The world’s top ten goat-producing countries are China (172.9 million), India (124.5 million), Pakistan (52.8 million), Sudan (40 million), Bangladesh (34.5 million), Nigeria (27 million), Iran (26 million), Indonesia (13.2 million), Tanzania (12.5 million), and Mali (11.4 million).

Judgments based on intuition aren’t always accurate, but if you feel uncomfortable with any part of a seller’s presentation, seek elsewhere.

AFTER THE SALE

Sellers will often deliver your goats for a modest fee; it’s the easiest way to get your purchases home. You can, of course, fetch them yourself if you prefer or if the seller doesn’t deliver. Diminutive goats such as kids and adults of some miniature breeds are easily transported in high-impact plastic airline-style dog crates stowed in the bed of a truck (secured directly behind the cab to block wind), in a van, or in an SUV. Horse trailers, stock trailers, pipe racks, and topperclad truck beds all suffice. Whatever you use, bed the conveyance deeply for the animals’ comfort, and use tarps to keep goats out of direct wind and drafts.

Goats mustn’t be stressed in transit; stress equates with serious, sometimes fatal, digestive upsets. Keep everything low-key. Avoid crowding. Provide hay to nibble en route, stop frequently to offer clean drinking water, and dose your goats with a rumen-friendly probiotic paste or gel such as Probios or Fast Track before departure and after you reach your destination.

Have facilities ready to receive your goats, and feed them the same sort of hay and concentrates to which they’re accustomed. Many sellers will provide a few days’ feed for departing goats if you ask. Begin mixing the old feed with the new feed to help the goats gradually make the change. You won’t want to further stress newcomers by immediately switching feeds.

Isolate newcomers from established goats or sheep (goats and sheep share many diseases) for at least three weeks. Deworm them on arrival, and if their vaccination history is uncertain, revaccinate as soon as you can.

Kari Trampas’s LaMancha buck is a sterling example of his breed, famous for sunny dispositions and high butterfat milk. They originated in California, making them America’s own dairy goat breed.