SARAH LEVIN AND I shook hands at the airport, meeting for the first time. We stood outside the terminal, taking stock of each other as we made small talk. Then the two of us headed out, picking up coffees and driving into Cleveland. I watched intently, focusing on Sarah behind the wheel as she tooled along the highway into the city.

We were going across town to her office in Shaker Heights, passing close to some of Cleveland’s tougher areas. We left the highway so that Sarah could show me around. There was a reason for the quick tour. This young woman wanted me to see who she is and where she spends much of her days.

Sarah is a social worker who works with kids from the city’s poorest neighborhoods. Our trip now was taking us through some dicey districts. “As long as we are here,” she said, “I need to pick something up. It will save me a trip later.”

We pulled into a driveway in front of a house that had seen better days. Sarah needed to get a document from a client. I waited in the front seat, watching this small woman approach the silent house. The old wooden structure seemed foreboding, the neighborhood rough.

When no one answered the door, Sarah walked back past the car, holding up one finger, signaling, “Be back in one minute.” She seemed unbothered by where she stood, though this did not feel like a welcoming place. She disappeared around back and vanished. She has guts, I thought. She reappeared, papers in hand.

Sarah counsels troubled kids and their families at an experimental school that draws children from around the city. I had spent enough time in Cleveland during my years in the news business to remember journalists mocking the worn place as The Mistake on the Lake. A brief urban resurgence had given way to the feel of a Rust Belt town that could not keep up with a new era.

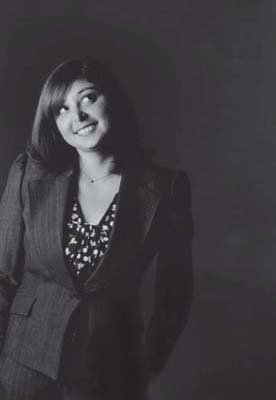

Sarah seemed to be smaller than life, a pretty version of Stuart Little’s kid sister, diminutive and always on the go. The two of us walked and talked, jumping or, in my case, stumbling back into the car to drive through more projects in areas Stuart would never choose to visit. Sarah seemed so small up against this urban wasteland with its big problems.

She described going into broken homes and dealing with hostile people, many of whom live with crack vials and cracked dreams. Troubled kids from that world can end up at Sarah’s school and in her life. “My friends ask, ‘Doesn’t it scare you to go into these projects and take chances to do your work?’” Sarah carries pepper spray when she remembers to, in case she is attacked. “Nobody bothers me,” she said. “I have been nervous at times but never really fearful for my life.”

There is another threat that she does take seriously. Sarah suffers from Crohn’s disease. She has a particularly bad case of that debilitating condition of the digestive tract. Crohn’s wreaks havoc continuously on Sarah’s already damaged body, creating daily doubts about her future.

Sarah pulled her red Volvo into the Fair Hill Center on the border of Cleveland and Shaker Heights on this steamy early afternoon. The July heat was oppressive, and the prospect of abandoning our air-conditioned cocoon, even for a short stay at her office, was unappealing.

Sarah looked fragile and walked slowly. “I am working just three days a week this summer,” she explained as we headed toward the office and our next breath of cold air. “I just cannot do anymore,” she said, “at least not right now.” She juggles sickness and her social work, and the two are not easy companions.

This inflammatory bowel disease compromises Sarah’s life each day. She seems exhausted beyond her twenty-eight years, as her soft, sometimes shaky voice betrays. “It is good,” she said softly, “when there is more time to sleep. I sleep a lot these days. I think a lot of the fatigue comes from the fact that I am always anemic.”

Chronic exhaustion is a byproduct of continual bleeding. Sarah had to have her large intestine removed, and the remaining upper digestive tract is so ravaged, it regularly hemorrhages into her belly. Bleeding is slow but steady, the blood working its way south to become rectal bleeding. “Internal, external, let’s just say bleeding,” Sarah said wearily.

She can speak openly without opening up in detail. Although she is a rock in her professional identity, she is uncertain socially and as a woman. This is not surprising; young women do not share the intimate specifics of intestinal misery with guys so easily. So Sarah lives as different people, one a shrinking presence, the other an expansive personality. A real-life incarnation of the Pushmepullyou, Dr. Dolittle’s mythical animal tugging in opposing directions from itself, her vulnerability vies with her resolve. “I am more the tough person who has days of being vulnerable,” she said. “Yeah, I do stand up in my life,” she exclaimed as if surprised by her words.

Today, the old Fair Hill buildings house adult daycare facilities, serving seniors who do not need nursing homes but require stimulation and supervision during the day, as well as the school program where Sarah works. The dignified old place used to house a mental institution. “It seems appropriate,” Sarah told me. Why? “My life is nuts,” she answered with a half-smile and left it at that.

As an in-school therapist, Sarah works in and outside the classroom with kids who have trouble wielding social skills. Her program is called intergenerational because teachers and counselors work with the seniors at the center together with the kids. Some of the youngsters have behavioral problems. “I am there to intervene and work with parents.”

“Does your career choice have anything to do with your health?”

“I went into social work because, eventually, I want to work with kids with colitis and Crohn’s.”

I watched Sarah out of the corner of my eye as we ambled down the school’s long corridors. She has a grown-up mission but cannot shake her little girl look. She is tiny, standing just short of five feet on a good day. Her face is round and pink. Her physical stature is an unhappy byproduct of imperiled health and pharmaceutical therapies for her disease. Drugs have resculpted if not deformed her body. And they have kept her alive.

By measures that go beyond inches, Sarah seems small in spirit. Wherever and whenever we have met, she has seemed solid as a survivor but tired from the steep vertical climb the sick must endure to reach their last stop, normalcy. Her journey has been under way since childhood.

SARAH LEVIN HOLDS no memories of a carefree childhood. In some real ways, she never knew the luxury of being a kid. As child turned toddler, adolescent turned adult, she was too busy straining to get through the day.

Sarah was barely out of diapers when the war with her body broke out. She was only three when the bloody diarrhea began. The problem quickly escalated. “My parents have told me I was pretty much sick most of the time,” she said.

Sarah’s earliest memory of dealing with the illness was undergoing her first colonoscopy, at the tender age of four. “Yeah, I was very unhappy to be in the hospital,” she recalled. “I was pretty scared and confused.” I remember my own horror at this un-fun procedure as an adult. I told Sarah I had been fifty. She laughed. “I got a Cabbage Patch doll for agreeing to do it without a struggle. What did you get?”

“A headache,” I answered.

Following the colonoscopy, Sarah was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, a chronic inflammation of the colon that produces ulcers and pockets in its lining. The condition can produce intense abdominal pain, cramps, and loose discharges of pus or blood and mucus from the bowel.

That was the beginning of a long pattern of being sick and missing school. The hemorrhaging got worse. “I think I was in second grade when I got really sick,” Sarah said. “I probably should have been hospitalized at that point.” When she returned to school, her mother, Joan, went with her. “I cannot believe she did this,” Sarah said, “but she would sit in the hallway all day.” Joan spent hours reading, at the ready in case Sarah got sick. “I was there for weeks,” Joan said.

Joan is an elementary school art teacher who was as concerned for Sarah’s head as for her body. “The issue was insecurity on Sarah’s part,” Joan explained. “She was embarrassed, running to the girl’s room, trying to make it before she got sick. The disruption usually came in the morning.”

The problem was that Sarah was taking oral steroids. The little girl was swallowing prednisone to calm her gut. As an unwelcome side effect, the steroid also took over the functioning of her adrenal gland. That, in turn, left Sarah terribly nauseated after she awakened, virtually every morning.

Sarah’s public vomiting was unpredictable, whether it was at a friend’s house or on the camp bus. “I sat in that hallway because Sarah did not want to be sick in front of her classmates,” Joan said. “She was so self-conscious.”

A hovering mother at school only accentuated Sarah’s sense of existing in a separate universe from the rest of the kids. Nothing is worse for a kid than being different. “By then, I felt like I was not the same, and I think the other kids probably thought I was strange.”

The kids were merciless. Why is her mom here? Can’t she go to school by herself? “At that point, I was not able to explain to other people what was wrong with me or what disease I had.” Sarah makes it clear she did not understand her own problems. “All I knew, really, was I had tummy problems. If somebody did ask me, I would say, ‘I have a bad tummy.’ I did not know more than that, certainly nothing about ulcerative colitis.”

There can be no memory, no precise fix on the moment of realization of serious sickness in an innocent child. It’s not as though Sarah woke up one morning and understood that she was different or that her future was in doubt. The process of awakening to the realization that her illness would be forever happened gradually and over time.

“It was instinct,” Sarah observed. “No one said anything about it to me.” She remembers no particular emotion. “I was not emotional about my illness when I was younger. I just had it. That’s all.”

Sarah’s childhood continued to be punctuated with frequent bouts of rectal bleeding and continual diarrhea. The discomfort, sometimes graduating to pain, became a defining piece of her young identity. “I would not be able to make it through the day without going to the nurse with a terrible stomachache.”

“It all kept happening, and I felt more and more different,” Sarah told me with no discernible emotion. “I just could not seem to get over it. I just knew that I was not like my friends. I do not think I knew how I was different, but I knew that I was different,” she remembered. “I had the experiences with kids asking me why my face was so round, which was from the steroids.”

Sarah’s identity of being different took hold, exacting its toll. Kids made fun of her, as only kids can. “I have this vivid memory; I think I was six years old, and I was in our skating club and I remember a little boy. He asked a bunch of questions. ‘Why is your face so round? Why are you so little? Why are you always on the end of the line in the skating shows?’”

These blunt inquiries marked the first time other children would point out that Sarah was different. “I guess I really did not know at that moment that my face was round because of the steroids.” Sarah said her parents did what they could to shield her, but there’s no way for a child to understand the difference between the innocent curiosity of another child and the hurtful comments of a bully.

Mom described the insensitive remarks of other parents who would ask blunt questions: “What is wrong with Sarah? Her face is so round.” All the finger-pointing bothered Sarah a lot. “I just did not know why I had to be different.” That became her lament, a recurring theme of Sarah’s song.

She looked away thoughtfully, as if staring at something over my shoulder. “‘Different’ really is the word,” she continued. “It made me sad, but the feeling that I was not the same stayed with me.” Sickness can be a lonely experience. “I was trying to feel that I did fit in, but the remarks felt like a slap in the face.”

As adults, some of us celebrate our differences. For a kid, nothing matters more than fitting in and drawing little attention as an individual. Sarah was getting noticed, and for all the wrong reasons.

Her mother and her father, Paul, were determined that Sarah lead a successful life. Such a strategy can guide an ill youngster through the minefields of childhood. “My parents never let me feel sorry for myself,” Sarah said. “They tried to do whatever they could to not make me feel like a victim. That was not an option. I am telling you, I was pushed into activities.”

Debi and Ben Cumbo fought the identical battle with young Ben a decade later. Keeping youngsters strong in spirit and facing forward is a piece of the struggle when illness comes to kids. Youth get sidetracked as other kids become the issue, replacing illness as the enemy. Kids relate to one another, not to microbes and viruses.

Sarah figure-skated, took up ballet, played the violin. She became a Brownie, then a Girl Scout. “Yeah. I did everything that my friends were doing, and my parents made it a point for me to be involved in as many things as possible.”

Of course, that particular approach to coping can become its own tyranny. “I was probably involved in more things than the average young child.” Mom was the driving force. Joan did suggest and push, though she encountered little resistance. “These were all things I wanted to do,” Sarah said.

Joan and Paul say with certainty that the battle became as much psychological as physical. Sarah needed to know that her life was all about what she still could do. The couple seemed as sensitive to what went on in Sarah’s head as in her gut.

At a 1998 luncheon for women of distinction in Cleveland, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation honored Joan Levin for making a difference in the life of a child. Joan quoted the powerful advice she received long ago from Sarah’s doctor: “You can take your daughter home and raise her with a sick child mentality, or you can raise her as a normal child, expecting from her what you would from any healthy little girl.”

Sarah’s dad, an attorney now serving as assistant law director for Beachwood, Ohio, a neighboring town, says, “My approach to treating Sarah normally probably was much more subtle than Joan’s was. Joan tended to hit things head on.” Paul’s style was more laid back. He was inclined to step away and let events unfold. “I just figured, you want to do ice skating, all right, skate. Play your music. I was never willing to think of Sarah as unable to do, that we had to push.”

The plan worked, but Dad still worries that Sarah may have misread signals. “Sarah may have felt I was ignoring her and downplaying real problems,” Paul said. “But Sarah did come through.”

Sarah’s parents set the bar high and expected the best from their child. “I agree,” Sarah said quickly. “I think that being able to participate in all those things, and my parents choosing not to allow me to stay home and moan because I had a stomachache, was the best thing that they did for me. I mean, that is why I am who I am today.”

The unanswerable question is whether a person diagnosed in childhood adjusts well because there is no basis for comparison. Sarah never knew good health, so, like Ben, she can’t miss what she never had. I, on the other hand, learned that I had multiple sclerosis when I was twenty-five and had enjoyed a normal life until then. For me, the shock of hearing such an awful diagnosis has stayed with me.

“Really, I started figuring out more about my problems at six or seven,” Sarah said slowly. “It was not as if a lightbulb went off.” Sarah just stopped. “I do not think my parents or doctors ever sat me down. I somehow developed this understanding myself.”

Sarah remembered looking through books, though not absorbing much about ulcerative colitis. She seemed to develop a sixth sense or overheard conversations about the disease.

“I think we addressed the problems as they occurred,” Joan said. “We just intuitively decided what was the right thing to say.” She thought for a moment. “We never sat down and said, just, ‘This is what you have, this is what you are in for.’” Joan assumed Sarah heard the term “ulcerative colitis” from doctors during casual conversations. “Things were discussed in front of her.” Growing up with an illness, with or without a name that means anything, probably did ease Sarah into the tough realities she will live with for the rest of her life. There may be a wrong way to tell a young child about a sickness. Probably there is no right way. “It happened slowly, but we did not dwell on my health.”

FOR SARAH, THE hardest part of dealing with disease has been taking the steroid prednisone on a regular basis. The drug of choice for treating irritable bowel diseases, prednisone has a wide range of side effects. I have taken the pharmaceutical a number of times, and all it did was make me fat and crazy. Ben, too, took the drug with some benefit and harm: it helped preserve his lung function but also retarded his growth.

We who suffer from a range of chronic or autoimmune illnesses can become captives of a tyranny of treatment. The drugs we must swallow, the needles we thrust into our arms and legs, come with a price. These wonder drugs can bring on reactions that make us wonder why we are doing this to ourselves in the first place.

For Sarah, prednisone became a daily ritual at age four. “My mom mushed it into apple sauce.” The drug has created a spectacular struggle for Sarah. It most likely has saved her life, but it has stunted her growth and softened her bones. And she has suffered unwanted weight gain on top of everything else.

As a teenager, Sarah suddenly began experiencing wild mood swings. “In the middle of a conversation, just one word or glance would cause me to burst into tears or jump down someone’s throat,” she said. Prednisone can make a person hypersensitive, a condition already common in adolescent girls.

Sarah was slow to connect the drug to her volatile feelings. “I knew about the other side effects,” she said, “but for years I just thought I was really messed up.” Joan, too, was stumped. “I attributed the mood swings, the ups and downs, to be about teenage girls and their mothers.”

One unresolved question for Sarah and her family is to what extent prednisone has masked her true identity. Powerful drugs do alter personalities and change behavior. “We do not know Sarah’s real personality because she was on steroids for so long, really from a toddler on,” Joan said. “How are we going to sort that out?” She sighed. “I wonder if we will ever know the real Sarah.”

For teenage Sarah, the hot-button issue was her looks. Teenage girls are particularly obsessed with their appearance, and not surprisingly, remarks about her distorted face and body “made me feel so alienated.”

Sarah switched drugs for a while. The new pharmaceutical was termed a steroid-sparing drug, intended to counter difficult side effects. But along came a new one. “I took the drug for a while but got horrible acne. It was a very big thing,” Sarah said. “I never had pimples before. Here was yet another crisis to deal with. For a while, my skin was all I thought about.”

Before too long, the prednisone was back. Sarah felt beleaguered and over time invented a dangerous game. She tried to fine-tune how much prednisone she had to swallow each day to get by. She was desperate to reduce the side effects, the moon face and weight gain that were psychologically so damaging.

The desperate move backfired, and Sarah found herself in the emergency room. The pattern continued, taking her to the hospital five or six times for extreme fatigue, dehydration, and increased bleeding. The sequence of crises was exhausting. Sarah was so weakened she could not pull herself out of bed. “Emotionally, it was terrible. I knew what I had done, and my body was out of control. I was a complete mess.”

Sarah remembers this time as being utterly devastating. “I was a mess because I knew I would be put on even heavier doses of steroids in the hospital, and the side effects were going to rear their ugly head. That was inevitable.”

“This was a self-inflicted wound.”

“To some extent, yes,” Sarah responded in a weary voice. “I think a saner person would have figured out how to find a happy medium. You either feel good or look good. A really sane person would have opted for feeling good,” she concluded. Then her voice went up a notch. “Side effects are so damaging. They are so ugly,” she added with a touch of the sullen. “Put yourself in my position.”

Common sense prevailed, and Sarah relented. The prednisone cycle was resumed and is now kept intact. Sarah does dance close to the edge but more carefully. “I finally know how to gauge it so I am about a week away from landing in the hospital,” she said, laughing. “I do wonder if ultimately the drug is worse than the disease,” she said. “It just might be. Honestly, I have tried to figure that out. I think about it, sometimes every day.” The question is difficult because pros and cons are extreme. Life without the drug might pay off for a while, with a patient looking better, that is, before the nosedive begins and picks up speed, putting the person in extreme danger.

That someone so young has had to build a life around a debilitating disease and powerful drug is cruel. And prednisone is the tip of the iceberg. “I take,” Sarah began, trailing off. “I take,” she repeated haltingly. “I take,” pausing once more and staring into the distance as she lifted fingers.

She began to reel off names of drugs. There were pills for pain, drugs for diarrhea; Cipro, which she has taken for six years because she is prone to infection; another antibiotic that she was worried about staying on for too long; Nexium, for acid reflux; drugs for depression. There were a few odds and ends, and then Sarah finished her list. “Oh,” she said, adding one more pharmaceutical. “I take something for nausea,” she said, naming something else unpronounceable.

“All told, how many pills do you swallow each day?”

“Hold on,” she replied. “Let me calculate this.” I waited patiently. “Eighteen pills a day.” Eighteen? “Eighteen. Eighteen pills every day.”

“Do you take them in one feeding?”

“No.” She laughed. “I take some in the morning, and in the evening, some before bed.”

“Every day?”

“Every day.” Sarah’s point about feeling different was sinking in.

I know the drill. For eight long years, self-administered injections ruled my life. Sometimes once per week, others three times in the same period. Some MS patients needle themselves every day. For me, pain or the discomfort were not the deal breakers. Only the rigidity of the ritual got to me. I had to do it. How strange to feel pleasure that the drugs appeared not to make a difference. That meant the stabbing could stop.

The state of siege inflicted by illness and drugs never ends. Always there is the awful question, What’s next? Whatever the answer, and always there is a next, fatalism hovers nearby. Things always can get worse.

WHEN SARAH WAS fifteen, she developed what is called toxic mega-colon. The sound of that condition was ominous. “Like, my colon just blew up.”

“You mean it ruptured?”

“No. It ballooned and there were out-pouches. It was very painful. I was really sick.” She was hospitalized and released in May 1995, the day before her sixteenth birthday party, which she almost missed. That summer was horrendous. Again, Sarah was taking high doses of steroids, with predictable results.

“I was very, very unhappy, and knew that people were looking at me and thinking that something was not right.” As always, reactions of others determined the measure of Sarah’s health in her own eyes. “I remember going back to school for my junior year, and a girl I was friends with said to me when she saw me, ‘Oh my God, what happened to your face?’ I was like, who says things like that? This was a miserable time.”

Sarah’s condition deteriorated. She was sick for much of the following summer. Serious problems just kept coming. She was bleeding and bloated and black about the future. “I was pretty miserable.” Unlike Job, Sarah was about ready to say enough.

“We did not say that out loud. The doctor said it for us.” Sarah’s doctors began the drumbeat, broaching the idea of surgery. You mean surgically removing your colon, the large intestine. “Yes. My colon was now badly malformed. It was free-floating and twisting. The long and windy digestive road was not tacked down anymore, as the doctors call a secure and stable colon.”

The plan would entail a two-part surgery. The first would be to remove the colon and do a temporary ileostomy, allowing the base of the colon to heal. That would mean Sarah would have a bag, the plastic receptacle for waste delivered directly through the wall of the abdomen. Later, a second surgery would reverse the ileostomy.

This was all too familiar. I had undergone the same procedure when I had my second bout of colon cancer. This procedure was not fun, the bags, hideous. Cancer is no fun. Neither are diseases of the bowel. The Levins had run out of alternatives.

Sarah’s parents took her to the Cleveland Clinic. The family sat with doctors to discuss the possible surgery. Sarah was seventeen now, young to be promoted to full partner in coming to a decision about surgery. “I had a lot of say,” she said. “I said ‘yes.’” “Suppose you had said no?” “I think my parents and doctors would have sat me down and convinced me, because they really believed that surgery would cure me. This would get rid of the diseased portion of my digestive tract.”

Doctors told Sarah she would be normal after the surgeries. They assured her she would be able to do everything her friends were doing. There would be no worries. “I was very excited about that and looking forward to a life with no medicine.” Surgery was the end game. “I felt certain the operation would cure me.”

Putting away the poison was Sarah’s real objective. “I knew I would never have to take those steroids again. Never. That was my motivation.” The drugs had taken such a toll on her for so long. “I had come to hate all the drugs.” If Sarah made that point once, she did so a hundred times.

The price tag seemed small. “The doctor did not use the word ‘downside,’ but he said that what you pay is that you go to the bathroom a lot, you get diarrhea a lot.” Sarah said she figured that would not be so different from the way she already lived. “I was used to having diarrhea, so that wouldn’t have been a huge new thing to deal with. And the drugs would be gone.”

Sarah underwent the surgery. Miraculously, her surgeon was able to spare her the ostomy, which meant no bag. “I could not draw you a diagram of what he did, but he avoided a lot of typical things that are done in that kind of surgery.”

A day later, a crisis. Doctors detected a problem. They thought there was a leak at the site of the surgery. Maybe this was an opening that had not been properly closed or, because of inflammation, a new hole had opened. “I was rushed into surgery at midnight. They had to call the surgeon, who was home in bed, and he had to race down to the clinic and open me up. Luckily, there was not a leak.”

But there was devastating news. A mistake had been made. Sarah never did have ulcerative colitis. The young woman was suffering from Crohn’s disease, a similar ailment. The doctors had realized the misdiagnosis only when they reopened her belly. “They said that the Crohn’s was evident in the pathology.” Sarah was cured of nothing.

Sarah has her own theory. “I think they saw the disease with their own eyes, there in the small intestine.” That would be the giveaway. Colitis is limited to the colon, the large intestine. Any sign of disease in the upper GI tract means it is Crohn’s.

The prednisone regimen for all those years would have remained because both diseases are types of IBD, and this steroid is standard treatment. The surgery might have been different, although Sarah believes operations would have been in her future anyway. “The mistake was a slap in the face because my expectations were crushed,” she says.

Sarah was curiously calm about the misdiagnosis. “This is a very hard diagnosis to make in small children,” she explained to me, “and I do not blame anybody. It can take ten years to straighten out.” Or longer, in her case.

“Okay, it is a difficult diagnosis in children, but you were sixteen when you went into surgery. You seem to be cutting the doctors a lot of slack for performing what may have been unnecessary surgery.”

“I just know it is a common mistake,” she said, holding to her line.

“That forgiving, huh?”

“I was angry in general and did not know who to blame.” She went on. “This was another case of, why did this happen to me? It never became an issue, like we were going to sue.” Finally she admitted to a strong family reaction. “Everyone in our family was angry and very disappointed.”

Sarah’s father, Paul, weighed in on the subject. “First of all, prior to the surgery, I remember that her colon was nonfunctional. The symptoms were there.” Pause. “I have no reason to believe that mistakes were made,” the attorney told me. I thought he was pulling his punches.

“Then, why were you angry?”

“This was anger at the situation. Sarah was just devastated when the surgery did not work. We all were.”

“Surgery caused more problems than I ever imagined,” Sarah said with unusual emotion. “I was sicker than ever. The period after the surgery was the worst, but the bad stuff continued.” She battled infections. The dosage of the hated steroids increased.

What once held the promise of a journey’s end had become another beginning. Sarah was seventeen and starting her senior year in high school. “Instead of the mind-set that I was going to be better, I had to admit to myself that I was not cured.”

Crohn’s has a range of severity, with Sarah’s case at the wrong end of the spectrum. Her colon, her large intestine, was gone; her small intestine was diseased. “I knew it would get worse and spread to more areas of my digestive tract.” How long the promise of no bag would hold is still open to question. “It was a punch in the stomach,” Sarah remembered. “I knew there were going to be real hard times ahead.”

Interruptions in her life increased. She had been thinking about college and saw more hurdles in her path. “I started missing huge amounts of school and needed tutors.” And the terrible side effects of steroids were front and center. “I developed terrible acne again. My face blew up. I had excessive bruising. The mood swings were back, and they were intense.” She ticked off her laundry list.

“I was miserable,” she said quietly. “The worst depression kicked in.”

“You must have been angry,” I said.

“My anger comes and goes. As I may have said before, I hate my body. My body has never done anything good for me.”

Dysfunction and discomfort are wearying, compounded daily. Anger and alienation from body, the prison that holds the spirit, imposes a separation from self. I, for one, have painful memories of looking in the mirror after surgery for colon cancer, gazing at the disfiguring bag on my belly. In that moment I felt as the though the real me was missing in action. Perhaps my container was somewhere at Baggage Claim, maybe in the hands of aliens. Or terrorists.

“That is how I feel about my body,” Sarah wrote in an e-mail one morning. “I am not in control of my body and what it does to me.”

“Do you feel alienated?”

“I am detached. You know, I want to trade my body in and get a better, working model.”

“Let me know if you find one,” I said.

Sarah’s view of self had changed. She had always seen herself as different. Now any move toward normalcy was gone. The young woman she has seen in the mirror and rejected over the years was, in fact, her. She was coming face to face with reality. Youth does not accept permanence, never mind the prospect of a compromised life.

Sarah has acknowledged that she sees her life as a one-way trip downward. A remission is possible, she says, but she knows her health will only slide out from under her. “It is inevitable that I will get sick again, and that I will require more surgery,” she said with transparent resignation.

“There is no going back.” There was a recent three-year gap between hospital incarcerations for her, and she told me she just waits. “I twiddle my thumbs,” she sighs, “waiting for things to fall apart again. Not a day goes by for me without thinking about this.”

LIFE WOULD GET tougher during Sarah’s last year of high school. She was in and out of class, surviving stints at the hospital, relying increasingly on her tutors. “People have said to me, ‘Oh, I remember you because you were always sick all the time.’ That is sort of what I was known for in those years. That makes me sad that people remember me simply because I was the Sick Girl.”

Between relapses, Sarah functioned well. “Every day that I got through without having some sort of crisis or some sort of problem related to my health was a great day,” she said, laughing. Between her junior and senior year, she had been well enough to visit Emory University, outside Atlanta, on a college tour.

Sarah struck what her family now calls a victory pose outside a dorm on campus. Arms extended overhead, fists clenched, a broad smile on her face. A photo from that day reveals a determined but frail young woman. That photograph hung on the family refrigerator until Sarah moved into her own apartment, where the snapshot remains on display.

Senior year started well. After intense sickness and tutoring, Sarah had finished the work from her junior year. “All right,” she reasoned, “this is going to be a good year. Let’s get off on the right foot.” But one Saturday morning, she stumbled. She had awakened with the vague sense of just not feeling well.

“I was like, ah, it is sort of my typical morning; I do not feel good; I will go to the football game and see what happens.” A festive atmosphere turned nightmarish for Sarah. Feeling sicker by the minute, she managed to make it home before collapsing. She was rushed by ambulance to a local hospital.

The emergency technicians hollered orders in the screaming ambulance. “You’ve got to bolus the dopamine faster! Her blood pressure is dropping!” Sarah had gone into shock. “These IVs are not hydrating rapidly enough. I want a central line into her chest now!” That is Sarah’s reconstruction of events with her mother’s help.

This already fragile young woman had gone septic. Her blood was toxic. The next morning, she was moved by ambulance, again to the Cleveland Clinic. “My blood had been poisoned by a new drug, and I went into multi-organ failure. Everything started shutting down, my kidneys, everything.”

She was on the edge. “I am told I was about an hour away from being put on a respirator. The doctor told my parents that I was not going to make it.” Then she surprised everyone and rallied. She stayed in intensive care for five days. When she was released and headed home, there was less of her than had left for a football game just days earlier.

“I was so weak that I could not get up the one step from our garage into our house. I remember just sort of crumbling to the ground and crying,” Sarah said in a flat voice. “That was when I realized just how sick I had been and how close I had come to not making it.”

Sarah did make it. A decade later, the young woman was curled up on her bed on a Sunday afternoon, feeling weak from the regular iron infusion she is given to treat her anemia.

“Did you ever want to give up?”

“No, but I was so scared and drained that I cried a lot, wondering if the rest of my life is going to be like this. I was at my wits’ end and did not know what would come next.”

“Somehow you muddle through tough situations,” I said.

“Yes. I do have to think that.”

“And you always will.”

“That is how you get through each day.” Sarah paused. “Then I meet Crohn’s families who have lost kids. It is so sad,” she said. “They just go on.” Sarah has learned a truth that has kept me going in my struggles with sickness. There is someone out there suffering more than I am.

Sarah suggested that her brush with death became a turning point for a number of her friends. “When these people realized how sick I was, they were shocked. There had been times when we had made plans and I could not go because I did not feel well.”

“They did not get it,” I guessed.

“Right. They would say, ‘Oh, take some Tylenol. You will be fine later.’ They did not realize the impact of my illness until they realized that I had almost died.” Then they became more compassionate.

Sarah’s fixation on the opinions of others continues. “I feel most at ease, I guess, with my old friends,” she said. “The newer ones have not seen how sick I can get.” She laughed.

“The rest of the world is the problem,” I said.

Sarah picked up speed. “Let them feel what it is like to desperately need a nap by two every day. They can swallow sixty pills a day or be on those steroids. Let them see what that does to your psyche.”

Self-absorption is emblematic of chronic illness. We become hyperaware of our long siege. Sometimes that is all we can see. And although we will not admit this, sometimes we do feel sorry for ourselves. That others have their own problems and take a less interested view of ours becomes unacceptable. It goes with the territory. Sarah is determined to suck it up and put her best foot forward. As with so many of us who struggle with chronic illness, Sarah badly wants to say the right things and project a calm resolve. Yet knowing that the strong face she shows the world is only a dream suggests how alone she can feel.

SARAH WAS AILING and apart from others during her senior year, staggering but staying on her feet. She was applying to college, badly needing to break away and fly. She occasionally found herself in the hospital that year, battling GI bleeds that would not end. “It was yet another low point,” she readily admitted.

“I was in the hospital when I was accepted at Emory. As a matter of fact, I was just out of intensive care. My dad brought me the letter.” Sarah had been accepted early decision. She smiled. “I almost had to laugh at how my life was going. That was the only way I could deal with it.”

The rest of the year went well. This was the end of an era, she hoped, time to turn the page. “High school was not so much about the lack of freedom. It was just not being able to do things because I was too sick to do them. By the time I went away to school, I was determined to have that normal college experience because my high school experience had been so unusual. I was ready to just fit in and not be the Sick Girl, and just do what everybody else was doing.”

Sarah craved and needed a real life existence. She wanted to be part of the social free-for-all most adolescents seek out. For a while, she achieved that dream, acting out like everyone else.

“College is when you are supposed to do stupid things.” She giggled. “There were more than a couple of times when I did some stupid things that I should not have done when I was not feeling well. I drank a lot and stayed up until all hours of the night. A lot of the time when I was tired or did not feel well, I just said, ‘Screw it. My friends are going out; I am going out with them.’”

The young woman discovered what she was looking for. “Sort of,” she laughed, “and there were certainly times when I did not feel happy with myself for the choices I was making.” So, take a number and get in line. “But they were my choices, not my mother’s.”

Sarah was turning into your everyday, stumbling, bumbling college student who just might survive the experience. “For the first time I had periods of time where I was like, wow, I am normal. I am doing what everybody else around here is doing. And I started to feel better about myself.”

Sarah was growing, she believes, in an odd way. “I think I went through my developmental stages out of order. When I was fifteen or sixteen, I was sick and was forced to grow up, to be more adult about things. I never had the chance to be the rebellious teenager and do goofy things.”

During the last years of high school, illness had kept her on the straight and narrow, even as her parents cut her some slack. They had felt so bad for her that discipline was tough to sustain. “I lied to my parents twice and got caught each time. A few months later I was in the hospital, so that was the end of that.”

Atlanta was not totally a crisis-free zone for Sarah. In 1999, when she was a junior, she was in a car accident and sustained a pelvic fracture from her seat belt. “Steroids had softened my bones,” she explained. “It is not clear that my pelvis would have fractured otherwise.” But aside from the accident, Sarah’s college years were relatively uneventful, at least by Sarah standards. “I was in the hospital once or twice a semester,” she remembered. “There were the GI bleeds and whatever.”

She returned to Cleveland after graduation and enrolled at Case University for a master’s degree in social work. During her final semester, the bad combination of a hard Cleveland winter and soft bones led to a fall on some ice. She broke her back and was forced to remain on bed rest for two months, but got herself to commencement.

THEN SHE WAS told by a specialist that she suffered from anorexia. Another brick had been added to her load. The eating disorder is the only piece of Sarah’s tarnished health that elicits a self-conscious response. She resists the labeling.

“I will not say I suffered from classic anorexia. My weight did drop to under eighty pounds. My point is that the problem was triggered by events,” she explained unconvincingly. “These were mostly breakups with boyfriends, once at the end of college and once again in graduate school.”

Sarah concedes that weighing seventy-nine pounds with her already small frame did point to a problem. “Yes, of course it was a problem. I did not want to eat.” She insists she was not starving herself. “Some days I ate a little fruit,” she argued, “but I never had days when I was eating nothing.” If not starving, then what? “I was so depressed. My life was changing before my eyes, and I could not function.”

Even as she got over crises in romance, her weight loss continued. She casually mentioned to me that her psychiatrist was the director of the best eating disorder clinic in Cleveland and that he strongly recommended treatment for anorexia. “I was very stubborn.”

“You mean you were in denial.”

Sarah giggled. “I think I was in denial.”

Those around her saw through her refusal to face the music. “They would say, ‘Are you kidding me? Look at you.’” Sarah may deny the diagnosis but cannot put aside the problem. She relates her eating patterns directly to the Crohn’s. Call it an eating disorder or a really dumb diet, she punished her body because of an image crisis and perhaps because of depression.

“I think subconsciously it is connected to not feeling great on the inside. I do not know that everything is connected, but I think for me it is.”

“You mean, to your illness.”

“Yeah, the Crohn’s has affected how I see my body, especially with the horrible side effects of those drugs.” She is particularly upset about the stunted growth caused by the steroids. “I would be about five feet, five inches tall if I had not been on those steroids.”

“That is a big issue for you.”

“Yes,” she snapped. “People constantly tell me I look like I am fourteen, which makes me really, really angry.”

We were driving around Shaker Heights. Sarah elaborated as we headed down the street where she grew up. “I have always looked young. I look at myself,” she continued, “and I am not happy. I feel I do not get the respect I deserve.”

“Everything just seems to be connected.”

“Yeah. I look at myself and I look at my friends, and I do not necessarily think I look younger than my friends, but the rest of the world does. People see me with my friends and think that I am someone’s little sister.”

“Tell me, why do you measure everything against other people instead of what you yourself want to be?”

There was a silence. “I think probably this is a bit too much about other people,” Sarah admitted. “It is stupid that I do that because I compare myself to other people my age who do not have chronic illnesses.”

“So, why do you do that?”

“I think I do it without thinking, Oh, I have a chronic illness. That is why.” Sarah is surrounded by healthy peers. “I probably mythologize their lives and do not think carefully enough why I cannot have the same.” Not only do other young women not enjoy lives as perfect as Sarah imagines but, by any measure, Sarah’s life is productive and, by many standards, normal.

“Yeah. I go back and forth in thinking that. It depends what mind-set I am in.” Sarah seems to wander all over the map on this. “At times I am okay and do think I am relatively normal,” she says without emotion. “I was able to go away to school and travel.” She sighs deeply. “On the other extreme, there are times when I feel abnormal and totally different from my friends and other people my age.”

MANY OF SARAH’S friends chose to leave home after college, but Sarah returned to Cleveland. “I did have the fantasy, like, wow, I wish I could do that.” She giggled. “I still have that fantasy.”

Independence at Sarah’s age becomes its own endgame. This rite of passage is how young men and women prove to themselves that they are grown up. To stay in the shadow of her parents is to admit she is different. Nevertheless, putting distance between herself and the security of a home that has sustained her is untenable and unthinkable.

“I THINK IT was a fear of finding new doctors,” Sarah said without embarrassment. “My mother also would be devastated if I left. She would take it personally.”

“Did you stay for her?”

Pause. “It was more for me.” Sarah stopped momentarily. “And there was making my mom happy, of course.”

Family dynamics in Sarah’s home seem frozen in time. Sarah’s tie to Mom is center stage, with Dad playing a supporting role. Brother Marshal has disengaged and is gone.

Sarah and I were drinking coffee again at Shaker Square, a few miles from her parents’ home. She was preparing me for our pilgrimage to Mom. My trip west had been built around spending time watching mother and daughter interact. After our coffee, Sarah and I headed for Joan and Paul’s middle-class homestead in Shaker Heights.

Joan and Sarah sat in the well-furnished family room wrapping small presents for a wedding shower Sarah was planning for a close friend the next day. Shaker Heights is a prosperous tree-lined suburb east of Cleveland, laid out in a uniform grid on land once owned by the North Union Community of the United Society of Believers, known as Shakers, so-named for their shaking bodies during religious dances.

This morning, Sarah sat on the floor, literally at her mother’s feet, looking up dutifully. For a self-possessed professional who walks up and down the tough streets of Cleveland, winning the respect of her colleagues, her little girl’s demeanor and voice seemed unfamiliar as she asked for guidance about each small detail. Which fancy paper would be used? How should the bows be tied? Sarah was waiting for instructions.

“My mom and I have an interesting relationship,” Sarah observed. “Some might say we are co-dependent, even enmeshed.” Obviously, this was not the first time these two were discussing this topic. Both women spoke with ease as we discussed how insidiously a chronic illness works its way in to define important relationships.

“In some part, this is the result of my Crohn’s and the fact that for a significant part of my life, I only had my parents to rely on.”

Joan believes that her aggressive approach has worked for Sarah. “My exacting standards and high expectations have helped Sarah rise to the occasion.”

In recent years, Sarah has struggled to break old patterns, if not burst free. “Once I hit my early and mid-twenties, I wanted to make decisions for myself,” she said in the family room. Of course, that is what anyone at that age wants. “But by that time, my mom was so involved in my life.” Sarah paused, glancing at her mother. “She is a control freak,” she added evenly and with no hint of humor as her mom listened without objection. “In the best sense of the word,” Sarah threw in, giggling. “It is impossible for my mom to let go and not put her two cents in. Always. ‘Oh, you made a mistake.’ ‘You should have done this or not done that.’” Yet, there was no discernible tension in the room. They had been over this ground before.

But Sarah’s baseline of dissatisfaction with the relationship runs deep. “She will constantly say that something I do is immature, something I have said or the way I respond to something is not appropriate or good enough,” Sarah continued.

Sarah admitted the criticism can be on target. “Oftentimes it is, but I think it is because even now, at twenty-seven, I am still learning how to be more independent, learning how to say no to my mom.” Pause. “No, Mom,” Sarah said, turning toward her mother. “This is my life.”

For Sarah, this is serious stuff. Steroids cause easy bleeding and bruises. She may want her freedom, but the line between needing help and feeling overly controlled is blurry, particularly when the fight for freedom can come at a steep price. “It has definitely caused a lot of tension in our relationship.”

Sarah clearly wants to rewire the relationship. “Most women have mother-daughter relationships that evolve into a friend relationship. I think my mom and I became friends too early, out of need. Then my mom wanted to go back and still mother me and guide me more than I want.”

There are no villains here. These are two loving and vulnerable women who cannot seem to break old habits that no longer satisfy. “I need my independence,” Sarah said to her mother.

For Sarah, her twenties have been a struggle for separation from a mother who unwittingly may have evolved into being overbearing. “I have this complex dynamic with my mom that no matter what I do, I am never going to be good enough.” By now, I was watching Mom. Joan’s wince was slight, but she took the emotional fire.

“Sometimes I feel like I am being put down. I feel like I am a failure to her,” Sarah finished, turning back to me.

Joan seemed to recognize Sarah’s feelings. “The downside of my pushing,” Joan said, “might be that Sarah worries about how others will see her if she cannot live up to those high expectations in the future.”

A bit self-serving, it seemed to me. Sarah is a grown-up, though she does keep going back for more. “I think that is very true,” Sarah readily acknowledged. “As much as I, both of us, talk about changing our relationship, we always go back to our same old ways. For the most part it seems to work.”

When Sarah and I talked later, I asked if there would be any resolution. Sarah chuckled. “We recognize our patterns and acknowledge who we are. You know, we are never going to fix things. Right?” A pause. “By now it is almost a joke.”

A week later I asked more seriously. “Are you both, in your own ways, casualties of chronic illness?” Sarah thought overnight and responded by e-mail.

“I see my friends and other people my age living away from their families, being totally independent, not having to worry about insurance, medical bills, and whether or not they forgot to take a pill at the right time. I wanted to be taken care of again. That is probably when my relationship with my mom really began to veer off course.”

Sarah goes back and forth about her mother. “My mom has devoted her life to me and my health care needs. I feel indebted to her.” Sarah criticizes her mom, and the guilt sets in. “I feel like nothing I can ever do is going to be good enough to repay her for all she has done for me.” Then: “I think she is finally realizing that she needs to take a step back.” Finally this: “I do not want you to write anything bad about my mom.”

Sarah went on candidly about the state of her emotional heath. “I often wonder what I would be like if I did not have Crohn’s, and had not been on steroids for my entire life. Would my personality be the same? Would I be more ambitious, more independent?”

The psychological pressures and problems stemming from this disease can match, maybe surpass, the purely physical. “I think that the emotional side effects have been worse,” Sarah confirmed. “Mood swings, depression, irritability, short temper, even distraction when on high doses of prednisone.”

These battles of the mind scared Sarah into staying close to home. “Yes,” she said slowly. “I think that having parents to rely on for the physical stuff has been important.” Then she switched gears. “I look to them for emotional support,” she told me. “There are times that we help each other. We feel crappy together.” Does it help? “Yeah,” she said. “It makes me feel less alone or even less alienated.”

Sarah’s condo is located just down the road from her folks, and she is anything but disengaged. After intense consultation with Dad and some financial assistance, Sarah purchased a two-bedroom condo in Mayfield Heights, another suburb of Cleveland. This is a grown-up place, with an attached garage, back porch, and all.

“I always feel like I am a few steps behind everyone, racing to keep up,” Sarah said as we sat in the new condo. She seemed to feel she was catching up. “In getting the job and now buying the condo, I do feel closer to the others.”

But not enough. “Then reality comes back,” she said in a tired voice. “How I feel, my lack of energy and all the problems are still there. I am still behind everyone else. That is why I need my mother.”

Living in Levin Land is a mixed blessing. No scenario better demonstrates the co-dependence, an arguable downside to proximity that Sarah and Joan have created for themselves, than the night of the big cleanup. “Sarah had been schlepping herself out of bed every day,” Joan said. “‘When is she going to clean and do everything?’ I asked myself.” One can guess the rest. Joan got the job done. “I just could not stand that the floors were dirty and clothes were not washed.” Yes, but those were not your problems.

“So, Joan,” I ventured, “are you planning to ever give Sarah some room and even stay out of her face?”

“Are you kidding?” she laughed. “I am in there with both feet.” I had the uncomfortable feeling she was not kidding. “You cannot change it,” Joan added, “much as I have tried. I do say I am not going to do something. Then I do it and get angry with myself. Then, of course, I rationalize why I did it.”

Small wonder Sarah cannot shake her unanswerable questions. “If I were healthy, would we be as close as we are?” she wonders out loud. “Will we always be so co-dependent?” And the conclusion Sarah had resisted or at least withheld until now.

“I think that if I did not have Crohn’s that I would have ventured out on my own after college, far from home. I felt the need to come home because it was safe. I was back in my comfort zone.” Case closed. Almost. The impact of chronic illness on a family is powerful. When one family member suffers, family dynamics change, apparently for good. Illness is a shared ordeal.

Paul Levin had always spoken openly about his tendency to allow Joan to take the lead in times of crisis. Now he seemed to feel like an outsider in the discussions of mother and daughter. “I was just talking to my dad,” Sarah wrote to me. “He said that he sometimes feels he did not take an active enough role in the medical part of everything, but agreed that he was usually the one who provided more constant emotional support.” Weeks earlier, Sarah had characterized Paul as her buddy. “We are pals.”

Sarah is circumspect. “With regard to the roles that my family members took on as we dealt with my Crohn’s,” she said, “I think that everyone fell into the role that he or she was meant to play. My mom was the one most in charge, both of my medical care and my life.”

Young Ben Cumbo had expressed his share of anger. I live every day with mine. Sarah does not need a human target for hers, though I think she has identified one. She seems angrier at Mom than she will say.

SARAH’S LARGEST CONCERN is her isolation from others. “There are times since I have been out of college that I have separated myself from the rest of the world. I did not have a lot of friends when I first came back to Cleveland.”

That was a strategic maneuver. “I felt like it is a lot easier to not have friends and have to explain my life story. Like, ‘Okay, nice to meet you, and this is why some Friday nights I might be tired and not want to go out.’” Sarah seemed tired of explaining her fatigue. “It is very overwhelming,” she said in a weary voice. “I had done that in college and I had done that in high school. I am tired of filling everyone in.”

Instead, she spent a lot of time with her parents. “Only in the past year or so have I made an effort to isolate myself less and to get myself out there and meet people.”

Three years ago, in spite of her self-imposed solitude, Sarah discovered a special man, Ben. The two had met on a Jewish Internet dating site. “She asked me out,” Ben kidded, gesturing to Sarah. The three of us were sprawled on couches in Sarah’s living room. “I did not!” she yelled back.

“My personal ad said, ‘Good things come in small packages.’” Sarah was animated. “She posted a good picture,” Ben responded, adding, “She gave me her number but I had to ask her out. Let us just say that Sarah did not make it difficult.”

Sarah and Ben are an unlikely couple. Ben is an outdoorsman. Sarah just wants a room at The Ritz. Ben works in the auto insurance industry, in a position he says offers no challenges. The man seems bored with work but captivated by Sarah. They became engaged in February 2006, and married in October.

A serious relationship was a long time coming for Sarah. It was her ticket away from solitude, something she badly wanted. “Seeing my friends start to get engaged and actually get married just made me realize what was missing for me,” she told me. Marriage makes her feel whole.

“Being married makes me feel more normal, like I am back on the path of doing what my friends are.”

“That matters a lot to you.”

“Yes,” she responded. “Despite the fact of a serious illness, somebody loves me. I do take great comfort in that.”

Sarah had always questioned if she was attractive or appealing, and if somebody would want to date or even have anything to do with her. “I felt that I came with a lot of baggage.”

Our culture celebrates physical perfection. Women must be flawless. They are certainly not supposed to go near the bathroom, never mind use it. Sarah knew what she was up against.

A young woman can be as vulnerable to those cultural constructs as anyone on the planet, buying into the preposterously idealized view of her gender. “Not this one,” Sarah practically shrieked. She guffawed at the very idea that, given her problems, she conceivably could buy into that glossy magazine stereotype. “A woman burps or passes gas in public,” she went on. “Oh, my God, I have never seen a woman do this before.” Shocking, isn’t it? “There is such a double standard.”

“That may be,” I pointed out, “but you are its victim.”

“One of the first things I used to do is make everything clear when I would first meet someone.” Crohn’s calls for full disclosure. “Yeah,” she responded. “I would say, ‘I might fart in front of you, and I go to the bathroom a lot. So, if you cannot handle a woman who does those things, I will not see you.’”

“Sounds like risky business,” I said. Throwing down the gauntlet may not be the best way to attract members of the opposite sex. Of course it does identify and separate the squeamish efficiently.

“A lot of guys would say, ‘Wow. I am glad you are honest about that.’” Then what happened? “Well,” Sarah said without hesitation, “if there was some kind of connection, then we continued dating. I have never had a situation when someone just left because of that.”

Sarah was smart to open up about her problems in these social situations. Ultimately, it spared all parties discomfort further down the road. “People have said this is not something you need to talk about on your second or third date.” Sarah sounded casual enough but sure of herself.

“I think it is one of the most important things to talk about early.” She stopped. “I need to know peoples’ initial gut reaction to my illness and how they are going to deal with this stuff.” She was not done. “And another thing,” she said. “Parents can be the problem. The so-called grown-ups can say, ‘We do not want you marrying a sick person.’ That is unfortunate.”

Sarah summed up her situation. “There are just unpleasant things, which are not ladylike. The physical truth is not something that guys want to think about or deal with. It is a very unglamorous thing.”

Sarah made clear that this was not some abstract issue. “It was embarrassing at times, being out on a date and having to go to the bathroom, and spending ten minutes in there, and the guy is wondering what is wrong with you. ‘Oh, I had a bad attack of diarrhea.’”

Ben took Sarah to a Mexican restaurant on their first date. That was smart. “I was very concerned about our first meeting because I was on prednisone at the time,” Sarah recounted, “and I looked completely different from the picture he had seen. I was afraid he was going to see me and say, ‘Oh, my God, who are you? What happened to you?’ My face was so puffy.”

Each seemed to be trying not to get too serious the first time out. Later in the evening, they moved to a bar. Sarah admits to being a little drunk when she broke the news to him.

“She kind of worked it in, like it was this big deal,” Ben interjected. “‘There is something I have to tell you,’ she suddenly said.” Ben could not imagine what he was gong to hear. “The mind goes wild: What? Does she have a third eye? Sarah said, ‘I have Crohn’s Disease.’ There was nothing to connect it to.”

“Did you run for the fire exit?”

“No,” Ben replied. “Why run? I did not even know how to spell the disease. I did not know what it was. I thought, ‘It will not be a big deal.’ I found out later I was half right, half wrong.”

As someone who had gone through dating and considered when to reveal the news about my MS, I understood how vulnerable Sarah had felt. You want to do the right thing but it’s hard to know exactly what that looks like. The information we hide automatically becomes dark to us, something to fear. We then expect the worst from others.

“The Crohn’s has not affected our relationship at all,” Ben said almost one year before the engagement. Right, I said to myself. Stick around. “I do not think I have dealt with that aspect of our relationship yet,” he said two sentences later. I rest my case.

Even in a relationship that offers so much promise, serious illness is difficult to process. Couples genuinely believe that things will be okay. That they will work it out. Meredith and I discussed my MS in our early years together but we brushed off the unthinkable too easily. Worst-case scenarios do not carry the ring of truth. What might happen differs from the certainty of what will.

“I have no way of knowing things will be fine,” Ben had said. Ben is a thoughtful and cautious guy. He weighed each question carefully. “At no time has the disease interfered in a real way. So far it is small stuff, tiredness or bad moods. Nothing severe.”

Intimacy was Sarah’s worst fear. “Intimate relationships are very stressful,” she had offered. “I worry that something is going to happen when we are intimate.” Details were omitted. “At this point, Ben and I are comfortable enough together that if anything does happen, he will be fine with it. It just takes getting used to.”

This is tough stuff, especially for young people poised at the starter’s line. Who would disagree that a strong physical attraction is a defining piece of a romantic relationship? Sarah and Ben are already tailoring their expectations by necessity.

“I think we have a less exciting physical relationship than a lot of people our age,” Sarah had said. “But it works for us.” She walks back and forth between romance and realism. She accepts the reality of her situation but wishes things were otherwise. “The whole subject can stress me out. Sometimes I have a bad stomachache instead of the headache. So it is, ‘Not tonight, dear. I have a stomachache.’”

Sarah thought that was pretty funny. She was serious, though, struggling to see her glass as half full. “Ben and I connect, and we enjoy each other’s company on so many other levels. This is not an issue at all,” she argued convincingly. “Ben gives me my space.”

Despite Sarah’s upbeat demeanor, it was clear that this was not an easy subject. “It makes me wonder if we are normal compared to our friends.” Again, Sarah fell into her pattern. “I feel like it is disappointing to Ben. Then I transfer that to myself. I feel like I am a disappointment.”

“I think the physical relationship matters a lot more to men,” I said.

“Yeah,” Sarah sighed, “and Ben is a guy.”

”Do you sense any dissatisfaction?”

“Ben says, ‘No, that is not the case.’ I still have that thought in my head.” Sarah slowed down. “This relates to the whole body thing. Sometimes I feel bloated and ugly.”

“Are you self-conscious with Ben?”

“Mostly I have grown out of it, except when I am having a bad body day.”

The subtext for our conversation about intimacy and related issues is that Crohn’s disease is a moving target. However slowly the condition progresses, it moves in one direction and will get worse. “I suppose I will have to rise up and meet my piece of the challenges,” Ben answered carefully. “If her parents will take care of Sarah’s physical well-being, I will do the rest.”

Sarah seemed as taken aback as I when she learned of Ben’s remarks. “It surprises me a little that he says that. I thought he wanted my parents to be less involved,” she said. “Ben probably feels relieved that they will be there. He knows what I have been through and knows there are hard times ahead.”

“Is he freaked?”

“No. I think he has begun to prepare himself,” she answered and paused. “We do not know how he will react. Probably it is a comfort to know that my parents will be involved. That is not to say he will not take an active role and be a wonderful support.”

Ben was not the only family member keeping an eye on evolving roles. Joan’s antennae were up. “My fear is that Sarah is going to rely on her husband the way that she relies on me.”

“So what is wrong with that? I would think you would want that to happen,” I said.

“Truthfully, I do not want her husband to be her nursemaid. I do not want him to pick up where I leave off.”

“Are you worried about getting in over your head?” I asked Ben.

“Not yet, but that could be foolish of me. Look,” he added, “I do not like to think of Sarah bedridden and in pain.” He thought. “I know that could happen. I only have the smallest bit of knowledge.”

The subject seemed to make Ben tense. “I could be fooling myself,” he continued. He grasped for an analogy. “This is kind of like a war and being in the trenches. The soldier does not know what is over the hill.”

Ben revealed no doubts about his commitment. “None,” he said firmly. “I have removed illness from my mind. I set the Crohn’s aside and try not to factor it in.” That is a dangerous strategy, I silently said. It was time to leave this guy alone. “One more thing,” he offered. “We are incredibly communicative. We do a good job of talking.”

Ben was learning this: that which is Sarah’s will become his. “When you joined my life,” Sarah said to Ben. “You acquired a chronic illness. My family already has that chronic illness. It affects each one of us differently, but that is what happens. You have to work it into your relationship and your way of life.”

Sarah was determined that this relationship work. She had taken the lead in making Ben comfortable with Crohn’s. “Do you feel prepared to deal with the uncertainties of the future and my health?” she asked Ben. “Like the fact that I may have to have more surgery? Have an ostomy?” Ben answered quickly. “Yes. That is something we discussed five months ago.” His body language said, “Back off.”

Sarah long believed that having children should come before radical surgery, that an ostomy and bag can stifle a sexual relationship. “For me, the fear of an ostomy before I have kids is both psychological and physical. Yes, an ostomy could have an effect on sex.”

More finite concerns were in the front of Sarah’s mind. “Crohn’s can complicate a pregnancy. That is an unknown but a chance worth taking.” It comes down to the strength of the desire for children. “Ben and I want kids, and it is possible we can pull it off before there is any more surgery.”

The clock is ticking. “We want to have children in the next couple of years. I think I maybe can hold off an ostomy for that long.” That would be pretty cool. “That would be very cool.” The focus, rightfully, was on Sarah. Ben’s role as partner and source of support carries its own complications.

Five years from now, and perhaps forever, questions will remain. What any of us believes about taking on a spouse who is suffering from a serious illness is continually tested. We all want to be partners and lovers, not caseworkers. Our notions of what is rewarding and important will determine if the sacrifices we make are worth it.

Sarah and Ben took me to California Pizza, jammed with young people obviously hipper than I. It was a struggle just to walk in, never mind stand around and wait for a table. I could not move, but that was okay. I could not hear, either. I watched Sarah and Ben. There was an ease about them.

“I am in awe every day that you stay with me,” Sarah told Ben. “I feel that I come with so much baggage, that I am a defective person. It amazes me that you are still around.” Sarah’s words had that sense of astonishment, as if she and Ben lived in a dream from which she expected to awaken.

That insecurity rings true. “There is always a part of me that is waiting for the bubble to burst,” she said in a matter-of-fact voice. “Sometimes I think there are too many good things in my life.” That last sentiment contradicted many that had come before.

“And you have been burned before, right?”

“Yes.”

Sarah’s illness had barged into relationships before. “This is different. I have never been more secure. I know Ben is not going anywhere.” That calm confidence, too, seemed out of character.

On our long ride back to my hotel that evening through Shaker Heights, I asked Ben if illness had made Sarah insecure. Ben responded instantly. “If I saw Sarah through her own eyes, I do not think I would want to be with her.”

“But…” I said, leaning forward to coax the thought.

“But I see her through my eyes, and I am trying to get her to see herself that way.” Then Ben turned slightly toward Sarah, in the backseat. “I want to work my magic and make you see yourself in a new light.” He laughed softly. “I think this is going to take a while.”

He pulled the car into my motel’s parking area, and we kept talking for a few minutes. “Sarah is a good person,” he said. “Thank you,” she said back. Ben laughed. “And she knows what she wants and goes with her gut. I do not,” he chuckled. “She dives into the pool. I am testing it with my toe.” Ben was not hanging around just to play nursemaid. The young man got something he needed from Sarah.

Ben expressed a last, unsolicited sentiment before driving off into the darkness. “When Sarah is happy, I am happy,” he said. “When Sarah is grumpy, I find alternative ways to bide my time.” Ben laughed. Sarah betrayed a faint smile. She knew what he meant.

“Is a sense of humor important to you guys?” I asked.

“Capital Y, Yes, for sure,” Ben responded, though he implied that his jokes can fall on deaf ears. “Sadly, I am my best audience.” Then they each laughed. “Sarah cracks me up, too, which is nice. This has nothing to do with her Crohn’s. Sarah is a klutz.”

Sarah giggled. “If we did not laugh,” she added, “we would be crying a lot.”

EVEN THOUGH SARAH is frequently upbeat, clinical depression has opened another front in what has become a very long war in such a young life. Her depression is not just related to her Crohn’s. Clinical depression runs in Sarah’s family, primarily on her mother’s side. But the role of Crohn’s in the mix has to be a strong factor. Sarah believes that Crohn’s, in fact, triggers a genetic predisposition for depression.

“Did my illness trigger my depression gene? Did it stem from the steroids, or was it situational depression? I think it is a question that I will ponder for the rest of my life and take with me to my grave, which I do not plan on visiting for a very long time.”

What kinds of events provoke the depression? “Little things do, like coming home from work any day of the week, maybe with plans, and being so exhausted that I just have to get into bed and cannot fathom doing anything that night. That is when I’m like, ech, what is wrong with me?”

“You sound just plain weary.”

Sarah offered her take. “It does sort of feel like there has been a black cloud over me for pretty much all my life. As soon as one thing is fixed, the next thing breaks. As soon as I am back on my feet from one episode, I get in my car accident or I fall and break my back.” Chronic illness, we learn the hard way, knows no end. “My friends know but do not get it and just do their thing.”

“I knew after the surgery that I was a few degrees off-center.” Meaning? “Looking back, I think it was not so clear, but I was not feeling right.” Illness-related issues may have touched off the explosion, but the depression was there. “I think if there were no disease, I would have had bouts of mild depression.” We will never know.

Those who suffer from severe chronic illnesses can fall victim to secondary crises that follow not far behind. Signals can be subtle, problems slow to spot. “Things that once made me happy did nothing for me anymore.” Such as? “My brother and I were looking at cars. My parents were going to buy one for us to share at the end of high school.” Sarah remembered that a happy process became joyless.

“We were looking at Pathfinders. I loved that particular car. It just did nothing for me anymore. Something was wrong. I was numb. I started seeing a social worker, who I did not like too much. The whole thing was too touchy-feely for me, so I moved to a psychiatrist.” The doctor thought Sarah’s psychological problems were at least partially situational, Sarah’s term for Crohn’s-related depression.

“I started taking medication. Antidepressants.” Sarah’s psychiatrist had confirmed the depression diagnosis. Sarah’s physical health had been pretty good for a while. “Yeah, but I had those bouts with not eating and became an emotional mess.”

Many of us who deal with chronic illness are dealing with a cumulative burden, greater than the sum of its parts. It stands to reason if you put enough weight on your back, sooner or later it can be hard to stand up. “Just thinking back on everything that I have been through makes me depressed,” says Sarah. “The whole ‘woe is me’ reaction is not my thing, but there are days when I want to say that.”

“There have to be days when people like us say ‘poor me’ in our heads, if not aloud.”

“Exactly,” Sarah echoed. “I break down to my parents, but…”

“That does not count,” I interjected.

“Right,” Sarah responded quickly. “But with my friends and stuff, I would never say it.”

“Why?” I wondered. “These are your friends, your support system.”

“I try to put on a brave front,” Sarah answered. “I do not want them to think I am a complainer.” She has been there for them. “Yeah, and it is frustrating because I lend a shoulder for others to cry on when things are bad.” She paused. “No one understands anyway, so what is the point?”

Sarah continued. “I guess my Crohn’s constantly makes me second-guess myself and question who I am. It is a very unsettling feeling to constantly wonder who I am and might be if my situation were different.” That, of course, is a fruitless inquiry.

“I am very scared for what is going to come next and when it is going to show up and what it is going to be.” Those who suffer serious sickness know there is an ambulance with their name on it, parked just around the corner. “I imagine further surgeries and further complications. Cancer, probably. I am more likely to get some sort of GI-type cancer than the average person. Statistics show that.” Cancer festers in Sarah’s head, but she is too smart and strong to go there for long.

The lady continues to be tougher than she appreciates. A single-minded drive for success has carried her through operating rooms and into the schoolrooms of her chosen work. Her selection of a career path suggests a concern for others, even as she is absorbed by her own trials. Sarah’s stealth steeliness has served her well.

We visited the Beech Brook agency near Shaker Square in Cleveland. The renovated building houses school-based programs and out-patient services. I watched Sarah mingling with colleagues, filing reports, calling clients. The lady was all business.

“It is hard to know how Sarah keeps going,” I said to her former supervisor.

“It is this incredible desire to be like everybody else,” the woman responded, smiling. “Nothing is going to stop her, no matter what it is.” Even physical relapses. “Sarah has this drive,” she continued. “She says, ‘I know it is bad, but I am not going to let it get me.’” Sarah’s old boss laughed softly. “Sarah is like the Energizer bunny.”

“Do you think illness has made Sarah a better person?”