LARRY FRICKS AND I drove into a remote southern town to arrive at what was once Georgia’s most notorious mental institution, Central State Hospital. The institution dated back to the early 1800s, and once carried the quaint name Georgia Lunatic Asylum. That day, the mammoth buildings of the old institution stood silent, as if they belonged in mothballs.

At one position near a long incline, a 360º-degree pan revealed endless fields of graves extending in every direction. Nothing about any of the simple graves said anything of their occupants. Religious symbols were conspicuously absent. “The graves were not worthy of being protected and kept up,” Larry Fricks explained. “Many markers were pulled so they could mow the grass. Even in death, these folks were just forgotten.”

The man tried to hold back tears. “Growing up,” he began again calmly, regaining composure, “I was taught that out of respect, not to even step on graves. It is acknowledgment that a human has lived on this earth and that we are all connected.”

Over the years, the hospital became known simply as Milledgeville, after the town where it is located. “Behave yourself, children,” the admonition went, “or you are going to Milledgeville.” Generations of Georgians still talk about hearing that threat and calling a halt to their bickering.

The place was quiet and deserted on this silent September Sunday but still it was imposing, even threatening. The drab stone structures had been home, or rather prison, to almost fifteen thousand troubled souls at any given time. The hospital had been a warehouse for the mentally ill.

Milledgeville became a freak show in Georgia culture. Tourists flocked to the grounds to take in the sights. The facility housed the largest kitchen in the world, an awesome attraction on the school trip circuit. Larry’s voice choked as he spoke of the hospital’s horrible history.

Electroshock therapy, routinely administered with portable units transported around the floors, was a prime means of maintaining order. One amused superintendent is said to have routinely lavished praise on the “Georgia power cocktail.” Psychiatrists were heard, infamously, to demand of patients, “Did Georgia Power make a Christian out of you today?”

Larry brought me there because the history and meaning of the spot have haunted him for decades. “This place is the story of stigma,” he explained. “People were brought here and told that they have no role on earth anymore.” He paused. “This could have been my home if I were not white and middle-class and reasonably connected.” He paused again. “I am mentally ill.”

ONE AFTERNOON, MORE than a year earlier, Larry and I had parked among the SUVs and pickups in front of Ma Gooch’s Restaurant in Cleveland, Georgia. We sat in the front seat for a while, just down the steep dirt roads from Larry’s Appalachian cabin, northeast of Atlanta. We chatted on various subjects, though not about the point of our meeting.

A tentative quality to our new relationship was keeping Larry at a distance. Finally, we ducked into the small joint for a quick lunch. “I eat three meals a day,” Larry offered in response to nothing.

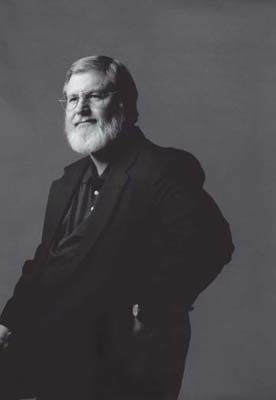

“Diet is part of recovery,” he went on. I nodded, and stared at him. He looked like a cross between Santa Claus and a lumberjack with his bushy white beard, checkered shirt, and suspenders.

He continued to explain the importance of discipline, ensuring enough sleep as well as establishing a proper diet, in managing a mental illness. “We can do a lot for ourselves.” A step-by-step strategy, a commonsense system of maintaining equilibrium and keeping an eye out for any blinking warning signs, is critical. “Vigilance becomes vital,” he declared.

Larry was taking it slow, hanging back and feeling me out. To do so seemed second nature for a man accustomed to fending off public ignorance of mental illness. This is a mighty slow dance, I thought as I stared at my unwanted soup. Since my colon cancer, I eat just about nothing during the day. Though soft-spoken and serious, Larry was good company, easy and empathic and warm to the people he encountered. Still, he was guarded with me.

Larry has bipolar disorder, once known as manic depression. He seemed old beyond his fifty-seven years, having traveled to hell and back. A map of his journey is visible in the lines across his face, there to read in his eyes.

Larry had been a young man when the terrible trip began. His dreams were crushed and the bright future that had been his ceased to exist. Mental illness became not an issue in his life but life itself. Even so, his demons are controlled now. He has become a master of self-protection in an unkind world. For him, this acquired skill came the hard way.

When we first met face-to-face in Washington, D.C., a few months before my trip to Georgia, I felt an instant connection. I trusted Larry’s drawl, the look in his eyes. We got down to business in his hotel room, words flowing tentatively, a tape recorder humming.

Larry wanted to explain his hesitation to share details of a deeply troubled period in his life. I was frustrated, ready for the flow of information. Conversations with Buzz had been tough. Buzz always stopped at first base, where God seemed to be coaching. Maybe Larry would swing for the fence.

“Please understand, Richard, I am somebody who went to the University of Georgia. I had good jobs and a lot of successes. I made money,” Larry said earnestly, getting warmed up. “Even with all that, after I was hospitalized, I was dumbstruck by the sense of hopelessness that people attach to mental illness and the message that came through to me.”

The man’s resentment at being marginalized was clear. We agreed to meet again in rural Georgia, Larry’s mountainous backyard. Soon enough, Larry’s well-worn VW Beetle was climbing into the foothills of the Appalachians toward his cabin on Buzzard Mountain. This was redneck country right out of Deliverance. “Scared?” he asked with a smile.

Once we left the highway, the population thinned and the road surface changed to dirt. We passed the trout pond at Turner’s Corner, and the incline grew steeper. Larry’s house appeared around the last bend through the trees. It was a rustic structure with an addition that looked as if it had been grafted on. A hunchback house.

We got out of the car, and two roaring beasts disguised as dogs walked in circles to check out the Yankee. Losing interest quickly enough, they sprawled around us as we sat on the old wooden porch, sipping lemonade in the warmth of a late-spring afternoon.

Later that night, we drove to the top of his property. We sat again, this time on a craggy hilltop beneath a clear sky. Larry had built an open geodesic dome that towered over us.

“Energy conservation is a piece of my spirituality,” he explained. “Doing the right thing in the universe matters.” We sat braced against the cold, leaning into a roaring fire as we devoured s’mores.

“So, let’s start at the beginning,” I said.

“Richard, that is a novel idea,” he answered with a smile.

LARRY GRADUATED IN 1972 from the University of Georgia with a major in journalism. By his own account, he was a party animal. “I had grown up Baptist. We did not drink. In college, I discovered alcohol,” he said. “There was peer pressure to party, and I joined a fraternity. I even became rush chairman.”

In the summer after his sophomore year, he had the first of a series of profound religious experiences. He was working for an electrician in Athens, where the university is located, and was sent to a church to help replace some old wiring.

Larry had time on his hands and nothing on his mind. “I was only a gopher,” he explained. He stood around, holding ladders and tools for long periods of time. “I looked, stared, really, at all kinds of stained-glass windows and took in the ambiance.” And?

“Something just came over me,” he recalled. “I felt an internal awakening, and it was profound at that moment. I had been an acolyte as a Baptist, always wanting to be connected. What happened was not so surprising.” Different? “Yes. I felt the presence of God.” Buzz would call that the presence of the Holy Spirit. “It felt real.”

Might that even have been an early sign of manic behavior? “No,” Larry countered, shrugging. “But my older brother certainly now sees this as a sign of things to come.” Larry put the moment into the context of the local culture. “This is a rural area and very Christian. This stuff happens to people all the time.” He chuckled. “Look. It did not matter, anyway. Months later I was drinking and dancing, you know, partying and back to the old lifestyle.” Larry said there may have been other, more classic, signs of manic tendencies back then. He points to his unusual high energy and productivity in college.

“I started a little business back then. I sold party favors and flowers for college events. I just went around and got orders from fraternities and sororities. We did pretty well.”

“Can you infer anything from that?”

“Maybe.” Larry paused. “I was beginning to speed up. Who knows what it meant?”

If Larry was accelerating, it was not a quick trip from zero to sixty. The move to mental disruption can come slowly.

After graduation, he was heading for another business opportunity when he got drafted and went into the army. “I did the six part-time years, with six months full active duty, and then two weeks in the summer.”

Larry had been a child of the sixties, partaking of the indulgences of the time while he was still in school. “I was smoking pot, listening to the Beatles, letting my hair down.” Still, there was the vague outline of a plan for the future, and any counterculture habits Larry had acquired would take a backseat to his drive to succeed.

Larry went into the real estate business with Glen, a high school pal. Glen’s father was a successful businessman. The possibility of an ice-skating rink somewhere in the Georgia heat took center stage.

“Glen’s dad thought it was a great idea.” Larry laughs. “It probably was not such a great plan, but, boy, it was a way to meet beautiful women.” In fact, Larry had no business experience. But the partners built a rink they called Iceland and did the interior by hand. Then the duo successfully negotiated a deal with the Atlanta Flames, a National Hockey League team, to move hockey practices from another rink to their new facility. Larry did business with the team’s trainer. “We gave him a washer and dryer to clean the jerseys. We were rolling,” Larry chuckled.

The Atlanta Flames grew into a glamorous and highly visible presence. Amateur hockey at the rink exploded. Larry was night manager and worked his way up to general manager. Finally, he became president of the business.

These were heady days, but psychological disaster was incubating. The presence of the Flames brought a faster life, and Larry began heading for the falls, all the while thinking he was only swimming in the fast lane. His pace quickened, and was easily explained away as strong and positive behavior for a young man in a hurry.

“My energy level was extremely high,” he remembered. “I was always on the go. I remember a couple of people shaking their heads and going, ‘Man, playing hockey and then going straight to play in a rugby game. Those are pretty strenuous sports.’” He grinned. “They are. But I had an energy level to do it, and I just kept going and going.” He was exhilarated. Mania was a mesmerizing, natural high. “It was great,” he said. “I felt so good. Man, there was no problem as far as I was concerned.”

Larry was a high roller now, going to fancy parties in the moneyed neighborhoods of Buckhead, an upscale section sitting in a northwest pocket of the city. He spent evenings, if not entire nights, barhopping with beautiful women. The high energy of his mania registered with everyone around. “The aura is attractive,” Larry said.

All systems were go. But you can only go for so long. Larry began drinking heavily, as an antidote to the high. “When your mind is racing and you have all this intense energy and you need to slow down, to sleep, that is what you do. See, I probably started self-medicating then.” I thought self-medicating was only a euphemism for overindulging. “No. I had to come down. Bad.”

“The other side of being revved up is that you come down,” Larry went on, “but you do not want to move too far down. That becomes depression.” Larry began doing drugs to shoot himself back up. “Does this make sense to you, Richard?” I nodded. “This is not a logical dynamic,” Larry said.

The formula eventually stopped working. “Alcohol appears to help, but in the end, drinking does not do any good because while it may slow you down and help you fall asleep, ultimately, it is not good for sound sleep,” he continued. Many of us learn that on our own. Drinking and awakening in the dead of night become debilitating. “I think the best I was doing was taking the edge off some mania.” Self-medication grew into sleep deprivation, which only exacerbated Larry’s condition.

The alcohol addiction was compounded by Larry’s growing taste for cocaine. “A couple of the ex-Flames I knew would snort it with me.” As part of the party scene, Buckhead was a hot spot for cocaine. “You could party all night. I had all the energy I needed.” The pull was irresistible. “When you are in the middle of that stuff, that kind of life of privilege, everything centers on lifestyle.”

The ice skating rink and surrounding land were sold in 1982. Larry was thirty-two. The sale made financial sense because the real estate was now worth more than the business. Larry shared in the profits from the deal, making two hundred thousand dollars. A short time later, he got married.

Clementine was the wealthy young woman Larry met on the social circuit, wooed and wed. The couple had been on the make, flying high on the Buckhead scene. After the wedding, the pair settled in a wealthy area of town. “We were the entitled. Hell, Richard, we owned two homes in Buckhead.”

The couples’ friends were the movers and shakers, part of the social elite. “We had been told that someday we were going to have it all.” Larry paused. “In fact, we were going to own it all.” How did it all feel? “Not all good,” he said. “It was a reach for me. My dad was a navy officer. We were middle class.”

“But it was also seductive.”

“Are you kidding?” Larry laughed. “Hanging out with beautiful people felt good. The rest just melted away.”

What no one knew, least of all Larry’s partners, was that Larry had embezzled ten thousand dollars from Iceland to underwrite the high life. He had justified the theft, telling himself he was just borrowing the money and would pay it back.

“It did not feel right,” he told me, “though my guilt was not about the money but what I had done to my partners.” When the rink and surrounding land sold, no one was the wiser. The secret remained locked away in Larry’s conscience.

Larry said he had no moral compass and no job. Still, the couple was financially secure. Clementine, whom everyone called Kimi, had a sizable trust fund, and the couple wanted for nothing. In addition to the two Buckhead properties, Kimi and Larry owned a house on Lake Lanier, exclusive property on the Atlanta watershed. The two kept a boat. The partying continued. Yet there was an unsettling feeling hanging over them, a lack of purpose.

Larry joined a favorite uncle in a venture manufacturing women’s blouses. From the beginning, the business had big problems and only stumbled along. “I think we had not thought out the concept well enough. Oh boy. I got involved in something that I had no experience in.” Larry remembers the enterprise as very stressful.

He and Kimi took a vacation, fleeing to the Fiji Islands in early 1984. For three weeks, the two hiked through paradise. “We were very happy,” Larry said. “Kimi even made the comment that it was the happiest she had ever been. We were very much in love.” As the couple was touring local exotica, word arrived that Kimi’s father had died. “We were stunned but could not get back in time for the funeral,” Larry said.

When they did pack up and return, a change in Larry became apparent almost immediately. Paradise was far behind, enormous stress surfaced from the hated blouse business, and his secret about the stolen money and guilt about his excessive lifestyle added to the weight of the load.

An explosion shook their lives.

“I HAD A spontaneous, spiritual awakening, a conversion experience.” The power in Larry’s voice was unmistakable. “It was like a sustained flash of light. All of a sudden, I broke out in a sweat.” Events played out over a three-day period. “I felt that I was wrestling with the deity, and at the end of the third day, I was just certain that God existed,” Larry recalled. “God had communicated with me and touched my life, and suddenly, all that mattered was that relationship.”

Larry insists to this day that the conversion experience was real, but an intense relationship with the Lord is a classic manic scenario. “It did happen, Richard.”

“Or you think it happened.”

“This event was the most transformative of my life.” Larry is insistent on that truth. “These religious experiences change people,” he said quietly. “I still believe that there is a spiritual realm. For me it started with good and evil and the Southern Baptist Church.” I just listened. “Apart from my behavior, a lot of things were becoming focused. It was a sense of, oh my God, I have missed a relationship with God in my life, and here it is.”

Larry had no strong personal faith at the time, no active religious affiliation that meant anything to him. “We were not active in any kind of church. The conversion seemed to be about God, not about a religion.” In reality, of course, the awakening was about Larry.

“God was actively in my life and communicating directly to me,” he explained. Our conversation grew intense during a drive through the mountains one sunny afternoon. The great outdoors, the bucolic countryside, could take us seamlessly to the doorstep of God in these talks.

“This was just part of my thought process, asking questions and then providing mental answers. As I got used to it, I was faster at it.” Larry was silently reasoning with the Lord. “Richard, that dialogue gave me a superhuman strength. It hooked me into a power I cannot describe. If you believe God is communicating with you, and I did, you feel invulnerable to just about anything.”

Larry celebrated the new relationship. “Yes, I did, wholeheartedly. Joyously. This was psychosis, of course. It is not uncommon for people with this kind of illness to have religious conversion experiences and awakening where they think that God is communicating not just with the world but to them directly. But it was real to me.”

Larry was convinced that God had a mission for him. He told Kimi that he had been touched by the Lord. Kimi was stunned and frightened for him. The reaction was compounded by her long-standing aversion to Christianity. Kimi stayed silent, though, unsure of how to process Larry’s experience.

“But as the behavior became bizarre because of what I believed God was communicating to me, I think it overwhelmed her.” There was no time for reassurance. “I went off on my mission to serve God. I was on a roll that lasted for months.”

Loose-cannon communications with God were traveling close to the edge. The assumption might have been that Larry had become just another born-again Christian. But Kimi saw nothing routine about the conversion. She was unnerved. And Larry was growing only more intense.

Bubbling over with enthrallment, Larry developed an appreciation for the forgiveness Christ taught and was ready to take care of old business. “I had to seek forgiveness for stealing the money,” he said. “I knew that. The time had come.”

He set up a meeting to tell his old partners about his misdeed.

“Did you go into that meeting believing God was at your side?”

“I was very frightened,” Larry answered, correcting me. “But my relationship with God was the most important factor. Kimi also went to the meeting.”

“Who else was there?”

“The stockholders were all there. I told them things had gotten out of hand, and I had borrowed the money.”

“And?”

“Richard, I did not know if they would press charges. My friend’s dad, our old boss, looked me in the eye and said the coolest thing. He said, ‘Well, you owned forty percent of the company, so you only owe us sixty percent of what you took.’”

Larry was spared a legal ordeal. This emboldened him and solidified his trust in God. “I trusted these communications from God more and more.” Larry now was taking his driving directions from the Lord. Literally. “I would drive around, taking turns and really not knowing where I would end up.”

He is careful to explain that he never heard a voice in his head. He would silently ask questions of the Lord and suddenly just know the answer. Yet he remained mum with everyone except Kimi. “This was not all right to share with people,” Larry said. “Instinctively, I knew that. I kept the experiences to myself.”

If Larry was losing it, he did so with common sense. “This is hard for people to grasp,” he said. “Even in my psychosis, there were islands of reality. Instinctively, I knew there are actions that can increase the possibility of being locked up.” He had acquired survival skills. “I had gained those insights. I was no fool.”

Discretion prevailed until, at last, enthusiasm overtook him. Kimi had been working desperately to protect him from friends and family, but could not hold him back. “When it all got stronger and more intense, I could not stay silent. I shared my experiences with the rest of my family.”

Larry’s older half-brother, Bill, found Larry’s revelations difficult to take. He had moved away from his own religion and was bothered by Larry’s zealotry. “I was put off by Larry’s excessive religiosity because of my own rebellion against the Southern Baptists, the dipped-in-the-blood-of-Christ sort of stuff, to the point where it was almost like fingernails on the blackboard to me.”

On a summer Sunday afternoon years later, we sat in Bill’s comfortable Atlanta home, a far cry from Larry’s mountain cabin. Bill’s wife, Sally, jumped in. “Bill’s friend was a psychiatrist. We consulted him, and he informed us about the nature of mental illness.”

“What did he tell you?”

“He made it clear that Larry was very sick.”

The family tried to persuade Larry to seek help. He refused. Soon his life began to crumble around him. “During this period, Kimi left me. She was trying to hang on to her life and needed a separation.” Kimi had stood by Larry, supportive, even strong. The foundation, though, had cracked. “I frightened her,” Larry said. Kimi had been swallowed up by events, overwhelmed by Larry’s intense relationship with the Lord. “I was still drinking, and by this time, Kimi had quit. I fully understand she had to leave.”

But at that time, Larry’s psychosis sent other signals. “I thought it was part of the religious persecution that any apostle of Christ could expect. I was not taking any medication yet. That would be part of Satan’s plan. Kimi, my family, doctors, they were all part of Satan’s plan. They could not understand I was called to live like people such as John the Baptist, totally committed to my mission.”

“Which was?” “Back then, my mission simply was to be a prophet of God, to do whatever God communicated to me.” There was no room for doubt.

Brother Bill is an attorney and understood that the family needed a strategy. “My brother is smart,” Larry said, chuckling. “He used my relationship with Christ to convince me to seek help. I will never forget him saying, ‘Look, you believe this is happening. We love you. Christ is about unconditional love. Out of love for us, would you go into this psychiatric hospital?’”

The answer was instant. “Yes.” In 1984, Larry checked into the hospital without resistance. He was placed in a detoxification unit because of his substance abuse. He was now God’s warrior in captivity. “God was telling me I had to get out. There was work to do.” Six weeks later, having changed his mind about life in the hospital and knowing there was a mission waiting on the outside, he went to court. He had learned a little law from others on the ward and knew his rights. He won his freedom because the hospital stay had been voluntary. Georgia law was clear; no commitment, no confinement.

Larry was not impressed by his diagnosis, manic depression. “These theories were things you have to put up with as a prophet of God.” Clearly, the diagnosis meant nothing to him, an attitude that would not change for a long while.

Denial, perhaps? How denial and psychotic behavior combine is anyone’s guess. “Denial in psychosis comes when we have our first insight that something may be wrong,” Larry said slowly, sounding sure of himself. “We do not want to accept the diagnosis or the prognosis. Then people go off their meds. That can be even worse.”

LARRY PROVED NO healthier after his return to freedom, picking up pretty much where he had left off. But now he had an incredible mission. “I was going to fly to South America, to Bogotá, and break up the cocaine cartel.” A friend alerted the family, and Larry’s father disabled his car to keep the young man close to home.

“This was scary stuff,” Larry said. “I was romanticizing law enforcement and the virtues of fighting drug dealers as an instrument of God.” He wanted me to understand the manic euphoria he felt. “I would wake up on this dopamine high and want to begin my work each day as a crusader for God. I was fully connected to God.”

With Kimi gone, Larry took up residence in a large house, a quadruplex on St. Simon’s Island. He had made the purchase with his earnings from the sale of Iceland, renting out three units and keeping one for himself.

St. Simon’s Island sits in the Atlantic off the coast of Georgia. As a young network news producer, I had visited refuges there for armadillos and birds.

“This was a beautiful place to be on a manic high,” Larry noted. “I would just ride around in my diesel van. I would pull up next to a police car and smile at the officer driving. I was convinced my car was bugged, and they knew everything I was doing. That was okay,” Larry assured me. “This was just part of the plan to bust the drug dealers. I was euphoric.”

Larry knew where federal drug agents trained near the island. He arranged a meeting with two agents and informed them that he had a reliable source in the cartel. The agents were interested. Larry did not tell the feds that God was fingering the drug dealers. He simply told them about a bowling alley where deals were going down. The agents seemed to believe him.

“What happened?” I asked.

“I do not have a clue,” he admitted.

His half-brother Bill does. Unbeknownst to Larry, Bill had quietly entered the picture, ready to do what was necessary to protect his younger brother. “First of all,” Bill said, “Larry had a gun. We were scared to death.” Bill had contacted the DEA agent and waved a red flag. In the end, Bill had to steal Larry’s gun and passport to keep him around and very possibly alive.

Chronic illness was now striking the entire Fricks family. A close family gets sucked into the crisis, whatever the cause. Larry’s family stayed in contact, desperately watching over him. “Yes. We love Larry,” Bill’s wife, Sally, said. “On my first date with Bill, we watched Larry play in a high school football game.”

That is how close Larry and Bill were. Sharing the burden of illness becomes less about obligation than about loyalty and love. “But yes, there also is a responsibility,” Sally told me. “Sometimes you do not want to get involved, but you have to. That is part of our value system.” She paused. “You learn. You cannot close your mind.”

Bill and Sally discovered a highly personal payoff that seemed to make the pain worthwhile. “Larry’s problems taught us a valuable lesson,” Sally pointed out. “One of our kids had a mental health problem involving depression. Drugs and alcohol were part of it,” she said quite openly. “Our ability to manage the crisis came from the experiences of living with Larry’s problems.” She smiled. “This is an illness. Do not freak out.”

Unfortunately, the oldest generation of the Fricks family had done just that. Larry’s and Bill’s parents could neither grasp the scope of the illness nor cope with it. In addition to Larry’s increasing psychiatric battles, another son, Stephen, was dying of AIDS. The parents were on overload.

“We are talking about two brothers who were confronted from a social standpoint with two of the most stigmatized experiences you could ask for,” Bill pointed out. “Homosexuality and AIDS.” Bill paused, looking at his feet. “And then mental illness. Our parents could not deal with either. To be hit with both of those at the same time,” Bill continued, shaking his head. “How do you explain the phenomena of all that was happening, especially to religious older folks?”

By the mid-eighties, that battle was in full force. Larry was drinking again, between short bouts of sobriety. “I would set out without money, and God would provide. I once traded a bottle of Vidalia onion salad dressing for a meal.” Every successful act of survival reinforced Larry’s belief that he was traveling a righteous road.

If he had no money in his pocket, there were funds in the bank. He decided he would invest in the shrimp business off the Georgia coast. “At this time, the shrimp industry was really struggling,” he recounted, “but if God is going to show you where the shrimp are, you know, I would have done just great.”

“And you believed that.”

“When you are in that state of mind, you do not make sound business decisions,” he said with a laugh.

And then there was the parrot. Larry had purchased a fifteen-hundred-dollar parrot from a local pet store. “Money means nothing to a person in a manic state. And God intended me to have that bird,” Larry explained with a wry smile. “The owner warned me that this was the meanest parrot you ever met. I could not be stopped.” Larry bought the bird. “All I remember is Larry driving up in a convertible with that parrot and talking about Jesus,” Sally told me.

Larry’s actions and attitude grew more irrational and less predictable. Bill and Sally could not summon a smile as they described behavior they were forced to confront. “Larry was running head on, just ramming Coke machines,” Sally recounted. “He seemed to go after anything red.” Why? “I really do not know,” was the subdued reply.

“I can tell you,” Larry said casually. “Coca-Cola had cocaine in it, originally. I felt that the Evil Empire of Coca-Cola was founded on cocaine.” If he could not take up arms and make it to Bogotá, he would fight the enemy on these shores.

Bill reiterated the frustration the family felt. “Look, we were not uneducated or totally clueless. We had the ability to call on resources,” he said in a strained voice. “But I cannot emphasize enough the pure terror we felt. Here is somebody you love, that you see doing this stuff that is unfathomable, and you cannot change the behavior, which is spinning out of control.”

“These must be tough memories.”

“Of course, but they are not always clear. On a certain level, you try to block these things out.”

Kimi ventured back, unwilling to abandon her husband of little more than a year. Throughout the siege and through the strain, there was something binding, holding them together. The two loved each other. “I did not want a divorce,” Larry said. “I had grown up in that southern Baptist culture, where you do anything you can to avoid divorce.” But Larry only increased his consumption, using alcohol to hit the brakes on his blossoming mania. “Our relationship was fragile,” Larry remembered. Something was going to give.

Larry was careening his way toward a second hospitalization, though he was too well oiled to see it coming. An overwhelmed Kimi got him into the car one night and drove him to the hospital. “I was so drunk, out of control, I have no memory of it,” Larry said. Large pieces of his life were evaporating into a drunken fog.

Larry was anything but steady on his feet when he hit the hospital. He collided with the admitting physician as he veered his way into the facility. The chair near the door seemed to flip over backward, and the doctor went flying, tearing his suit in the tumble. The exact details of what happened are not important. What matters is that the institution labeled the mishap a physical attack by a patient. This justified Draconian measures. For as long as Larry was inside, he would be maintained on Thorazine. Larry’s voice grew grim just talking about the drug. Bad? “Thorazine is a chemical straitjacket,” he said with steel in his voice.

“The drug is a hammer.” The pain in Larry’s words was clear. “When they put me on the megadose of that drug, I could hardly walk or talk. I remember trying to make it to the nurse’s station. Not a chance.” He was immobilized. “The mind sends signals, but nothing happens.”

Larry continued to stagger his way through the hospitalization, failing or simply refusing to accept that he suffered from a mental illness. Doctors had become the enemy. The view from deep inside the walls of the psychiatric institution instructed that doctors and patients did not play for the same team. “There were psychiatrists who truly believed that recovery is not possible, that we would never be moved through and out of the system.”

Finally, Larry had demanded a Christian psychiatrist. “He took me seriously,” Larry recalled. “This guy cared.” After being released, Larry told the psychiatrist he wanted to take responsibility for his life, to assume ownership of his illness. “This doctor listened and tailored my out-patient treatment to fit my beliefs. He knew I was a serious Christian.”

“This guy was feeding you Thorazine, Larry.”

“That’s true,” he responded immediately. “It is true.” But, Larry added, his doctor was the one to wean him off the hated drug as well. This psychiatrist did seem to believe in hope.

A drug-assisted assumption of hopelessness makes the patient’s job almost impossible. “It is very hard,” Larry said. “Doctors who have the hubris to assume a collection of symptoms shuts down the human spirit ought not to be practicing medicine.”

No doctor can predict the power of the human spirit. Too often, physicians do not look up from their charts long enough to understand. “Richard, I was exposed to doctors whose eternal hopelessness was all they offered.”

Larry was saved by his insurance company. Equitable discovered that Larry had lied on his application about abusing substances and cancelled his policy. He was discharged soon enough. “I honestly believe that the hospitalization was shortened when that money dried up.” No surprise there.

FOR A WHILE, Larry functioned normally on the outside. “I came out of the hospital more stable,” he says. “I was on my best behavior, sending the right signals to people, and watched how I acted pretty carefully. I was smart about my life at that point.” He still believed he had been touched by God, but he observed great discretion in public.

In a last-ditch effort to breathe life into their marriage, Kimi whisked Larry away to the Caribbean. She may also have sensed the nascent depression lurking in him. The two ran from reality to a yoga retreat on Paradise Island in the Bahamas, where Larry followed the rules, for a while.

Then one night, he swung over to the depression side of his illness, riding the bipolar continuum down. If Kimi’s Caribbean mission had been to help Larry find peace, his own goal became a secret search for something more lasting.

“I wanted to die,” he said. “I was out there, over my head in this beautiful water, trying to figure out how to drown.” Even as he sought that final solace in the depths, he failed to complete his objective.

When the couple returned to Georgia, Kimi left Larry for good. Their marriage had lasted just over a year.

“Did she know that as she was ending the marriage, you were trying to end your life?”

“Hell, no,” Larry answered. “Kimi was just scared.” A trust officer at the bank, a man she long knew, had warned her that any kids they had could carry Larry’s illness. “Kimi needed a life,” Larry explained. “The time had come.”

Larry’s feelings of responsibility for what his psychological state brought on his former wife cuts through him to this day. “I hurt that woman badly,” the man said. Guilt and shame are common emotions during recovery from mental ailments, Larry explained, measuring his words about the emotional carnage. “I have profoundly strong regrets.” He knows his actions were not premeditated, that he could not help himself. He acknowledges that Kimi stood by him until she could not take his behavior anymore.

“Kimi really, really tried very hard to help me. I do not want to create any more pain for her than I already have. I feel very bad about the strain on Kimi and my family.” In our years of conversation, Larry could not express his remorse enough. Emotional fallout from illness settles in layers.

WITH THE DEMISE of his marriage, Larry’s attention turned to mere survival. He desperately sought work, looking for jobs, anything, but with no success. “I even applied for a job at a local McDonald’s.” He stopped for a moment. More than money was at stake.

“Richard, I learned that work is so important.”

“Tell me more.”

“Work for us is treatment. The mentally ill are the most unemployed of any disease group, with an eighty-five percent unemployment rate.” The statistics are convincing. These studies indicate that, with the right support, mentally ill workers experience a lasting reduction of symptoms when they are employed.

Strain and pain were reaching a crescendo in Larry’s mind. He was alone at the lake house. Kimi had moved out, and Larry had been on his own since their return from the Caribbean. Over a period of weeks, a terrible depression descended on him. He was decimated.

“I got down on my knees and prayed,” he recounted quietly. “I was in so much pain.” I could see that pain in his eyes as he spoke. “I badly needed relief.” He paused for a few moments. I listened to his breathing.

“It gave me peace that I could control something.”

“But you were so out of control.”

“No.” Larry looked straight into my eyes. “I was going to kill myself. That is control.” He was calm and quiet as he spoke. “I was going to take an entire bottle of Thorazine I had tucked away from an old prescription. I had the bottle of Thorazine tilted up,” he said. “Pills had begun to pour out. Richard, my mouth was open and I was going there.” What happened? “The phone rang. It sounds crazy, but the ringing was sudden and very loud,” he said. The jarring, almost explosive ring startled him. “Literally, I spit out pills.”

The suicide spell was broken. Depression dissipated as mania reappeared over the following weeks. Larry was all over the emotional map, exhibiting erratic, uncontrolled behavior. “That just shows how unpredictable the disease is,” he said. In his head and through his body, he was speeding.

“I would sleep for two or three hours and wake up and feel like I could do anything. It was superhuman. I felt absolute clarity and energy, perfect direction.”

“But you had just tried to kill yourself,” I pointed out.

“Yes, but I was back on the roller coaster, and what I had done did not matter.” Larry stopped. “Besides, I was drinking again,” he remembered, shaking his head. The pattern was all too clear. Here was a man who badly needed to find the brakes.

Holed up at the Lake Lanier house, Larry was losing touch rapidly. By his own reckoning, he was coming close to a psychotic break. One afternoon, a few days into this siege, he was in the house, drinking heavily. “I remember just sitting around, thinking this is an evil place, satanic. This was where our marriage had fallen apart.”

Suddenly, he picked up his keys and walked to the van parked by the house on the water. “I got in, threw the van into drive, floored it, and crashed the thing into the house.” Larry recounted the event calmly. “The attack on the house was an attack on all that had gone wrong.”

Then he got out of his van and walked away. He did not turn back, even look over his shoulder, as he began a new leg of this strange journey.

Delusions were running the show. “I was convinced that there were children buried in a landfill in Cummings,” a nearby town. “A serial killer had placed them there, and God wanted me to go get the serial killer and find the children.” So Larry set off on foot, wearing a pair of sweatpants, no shirt, and no shoes.

He came upon a Presbyterian church. “I had come to believe that churches were a diversion from the true teachings of Christ,” he said, ever a committed soldier of the God Squad. “I got into a football crouch and attacked the sign in front of the church and knocked it down.”

Don Quixote approached the lake. Rather than going around the water, he elected to swim straight across. He dove in, wearing his raggedy uniform, oblivious to the fact that he had left his Speedo at home. “My sweatpants quickly became waterlogged, and the next thing I knew, they were off. I was buck naked.”

Larry completed his swim across the lake and found a house. “I knocked, and when a lady answered the door and found this naked man facing her, she started screaming.” Larry chortled. “I knew something was wrong. Even when you’re psychotic, there are islands of reality within that psychosis. I knew I had crossed a line.”

He ran next door to a small weekend cabin that was empty on this weekday afternoon. He broke a glass pane next to the front door and reached in to unlock it. He slipped inside and made himself at home. “God is good, I thought. The owner drank the same wine I drank. His clothes fit me. I took a shower, toweled off, put on his clothes, and sat there in his chair, drinking the guy’s wine.”

Larry heard a male voice shouting for him to come outside. He walked from the house. The man pointed a rifle at Larry, instructing him to stay there, perfectly still, until the police came. “‘Well, you will just have to shoot me,’” Larry remembered saying back to him. “I was thinking I was invincible. Thank God he didn’t shoot me. I walked up the driveway, and there was the county deputy waiting.”

“I broke the law,” said Larry, and noted that he had become a statistic. As government cuts social services, he explained, more and more mentally disturbed people are ending up in jail.

“Criminalization of people with mental illness is reaching epidemic proportions. The Los Angeles jail is the largest psychiatric facility in the country.” And chronic mental illness patients all too often become chronic prisoners. This is especially true for minorities and the poor.

“If I had not been white and middle class, I would have been booked, charged, put into jail, and then, what happens to you in jail, especially if you are in a manic state?” Larry said. “This becomes a downward cycle, a trap for the mentally ill.”

But Larry’s real estate buddy Jim was waiting up the driveway for him, standing with the deputy. “The deputy said he was there to assist me, and I needed to go with him,” Larry recalled. “I said, ‘Sure.’ I got in the deputy’s car, and we rode over to the jail. He put me in a cell alone.”

Over the years, prisoners had covered the walls with graffiti. Larry began decoding the messy markings, convinced they were messages from the Lord. “God was helping me connect certain letters in a code that no one else would be able to see. I was on a divine mission.”

Neither physicians nor family found the mission lofty. A psychiatrist evaluated Larry and reached the obvious conclusion that he had, in fact, suffered a psychotic break and needed to be hospitalized again.

LARRY HAD RUN out of choices. He was committed by the state, heading for his third hospital stay. The staff was waiting. “When I got out of the car, they sort of jumped me and carried me inside. Jim was still with me, and I remember turning to him and calling him Judas.” In Larry’s mind, Jim had betrayed God and his servant.

The staff put Larry into a treatment regimen, each time taking him to the same small room. “They forced drugs on me. The doctors can do whatever they want, because the patient is cornered.” Larry described his treatment as dehumanizing. “I was in what they called seclusion,” he remembered. “People could look in at me through a small opening in the door.” He was kept in restraints, bound to the bed.

What Larry cannot recall is what drugs they forced on him or how long he stayed in solitary. The pharmaceutical fog was too thick. “I have no idea what they were putting in me,” he said. “It probably was Thorazine.” A coldness creeps into Larry’s voice as he discusses his care.

Larry found saint and savior among the devils in this forced hospitalization. Each time he entered or left the facility, another patient who also suffered from bipolar illness extended a hand, each time saying the same thing. “‘I feel a sense of spirituality and a direct connection with God,’ he would say. ‘That is real and cannot be taken from me.’”

For Larry, who was starving for human connection, these fleeting moments had power. “This man was the first person I saw who understood me. He did not say, ‘Oh, that is all psychotic. Your awakening is not real.’ This man just said, ‘Look, I believe you.’”

Years later, Larry wrote in the The Journal of Dual Diagnosis about the power of meeting that individual. “My trusted peer had walked in my shoes and was not confronting my spiritual journey…as a psychological disorder.” Writing the experiences of illness had become an important piece of Larry’s own recovery, a way for him to establish perspective.

Too often, he said, what happens in forced treatment is that medical people act without thinking. Doctors force patients into non-psychotic behavior with such zealotry that they dismiss too many possibly positive and healthy dimensions of the patient’s mind and soul. They do not tolerate eccentricity or unconventional views.

Sometimes a fine line separates psychosis and off-center belief. According to Larry, conventional wisdom is not the only game in town. “In casting those judgments,” he said to me, “they dismiss what is your reality.”

Larry crawled out of that institution a broken man. The lake house was on the market, and Larry’s parents had stored his belongings in their basement. Proceeds of the lake house sale were to go to Kimi. “That was the least I could do for her.” Larry paused and went one step further. “I was crushed by this sense of the absolute hopelessness of my life.” He seemed to be giving up.

During one drunken evening out, a call for help from Larry’s date brought his father to the scene. Larry says he was sick of interference from others and in a confrontational moment with his dad, Larry tackled him to the ground. Then he drove away.

Larry and I sat on his porch on Buzzard Mountain as his story reached its denouement. The faint sounds of leaves rustling in the breeze made Atlanta seem far away. Larry told me about one powerful moment, a single act so long ago. “I buried my wallet,” he told me. “Larry Fricks could be no more.” This was twenty years ago, but he remembers clearly the meaning of that act.

“Everybody wanted me to go back to being who I had been at one time,” he told me. He defined that as a crazy John Belushi character. “That guy had crashed and burned long ago.” Memory of the moment, the night a life came unglued and an identity vanished, was powerful.

Larry purchased a six-pack of beer and checked into a Holiday Inn the night he wrestled with his father. Larry had run out of fuel. Nothing of the man remained. “I lay on the floor. I cried, ‘God, help me change,’” he recalled. “I fell into the fetal position, and I cried again. I felt such shame. Where had I sunk to?”

“I called my father later that night. ‘Okay,’ he said. ‘I will pick you up,’ adding, ‘No, we are not going to put you back in the hospital.’”

Larry had crossed a wide river during those predawn hours. The excesses of Buckhead were far away. He says he made a pact with God that night. He would continue to believe in his spiritual awakening, though he knew the rest of his life would have to change. “I knew that the way I was going, I would end up in and out of psychiatric hospitals for the rest of my life,” he said. “I needed new people and places and things.” This beleaguered man set out on a new leg of his journey.

PAIN AND SUFFERING, the ordeal of so many years, had forged a new sensibility. “I chose not to be angry or to give up,” Larry says with the conviction of a convert. “To be transformed would be to live to my potential. Recovery would mean a transformation for me, to realize I could own my life. I knew I had to take action.”

Larry began to repay debts. He got rid of the new RV, which had been purchased on credit. He sold all his properties. And he stopped drinking.

More tools than determination would become necessary to put this troubled soul on track. “I was disabled,” he recalled. “I would just sit in the morning, staring at the closet. I could not decide what to put on. I could not read a book. My concentration was gone.” Still, he was determined not to fall back on old patterns.

He volunteered to work with elderly patients at a nursing home, which became valuable therapy for him. Just as Buzz looked to the dying to teach him how to live, Larry turned to lonely, disconnected old folks to slip back into society. He concedes that he identified with their desperation. “The lives of these people appeared more hopeless than mine. I worked with them and got outside of myself.”

Larry accepted medication, and began taking lithium. “I had pushed medication away for a long time, which was a big part of the problem.” He struggled with the side effects of the medication. “I had shot up to three hundred pounds by now because of the lithium.” He started to lift weights under the tutelage of a new friend, Paul, who was a former Olympic weightlifter.

Although the pain was still all around him, he knew he could not play victim but had to become part of the solution. “I took responsibility,” he told me emphatically, a phrase he would repeat many times. That act meant learning and dealing with the realities of his disease. “I realized just how bad sleep deprivation is. I learned I can control my sleep patterns with medication even when I awaken in the middle of the night.”

Self-awareness led to proactive involvement in his own care. Eating nutritionally balanced meals became important for Larry in maintaining the chemical balance in his body. “The diet thing was kind of tough,” he said. “I had to just make myself do it.” His spirit, though, remained in tatters.

“I was in desperate need of a sense of purpose.” I was putting out résumés, searching for jobs everywhere. This was a long way from my career as the general manager of an ice skating rink.”

“Were you honest about your past?”

“I could not bring myself to tell the whole truth,” he admitted. “There were holes in the résumés. I could not explain where I had been.”

“Did you feel guilty about that?”

“What you should say about the past is a question I never stop asking.”

Larry was contacted by his former real-estate partner Glen. “He invited me to live with him in his condo and proposed a new real-estate partnership.” The pair formed a new company and bought a sixty-acre property. It was a good move for Larry in more than one way. The land had a house on it, and Larry moved in. “It was in Lumpkin County, which was dry,” he noted. When the property eventually sold, Larry stayed in Lumpkin.

“I also wanted to be of service and realized that real estate was not the way to do that,” he continued. “I began working with kids. They were troubled children, juveniles with alcohol and drug problems.” And Larry renewed his passion for journalism and began to write again. “Writing gave me something meaningful to do with my life during the day. I would use writing to get an identity back. I sent my columns to local papers.”

Larry hit a small gusher. “One local editor liked my work and encouraged me. He started publishing my stuff.” Seeing success was empowering. “I would see my byline and begin to weep,” he said, his voice cracking. “I realized I could make a contribution.”

“Did you make a living writing?”

“Hell, Richard, I made twenty-five dollars a column.”

Fledgling success had a seismic impact on him though. “It was a very important part of my recovery.”

“How so?”

“It meant that I had meaning and a reason to get up every day.”

“Did you see yourself as damaged goods?”

“There is a real trauma factor that other illnesses do not have. If you are sick and a pain in the ass to your wife, there is no danger of doctors taking you away to forced treatment.”

Journalists need boundless self-confidence to put themselves on the line, the hubris to stand by their stories and insist they are right. “Oh, yeah,” Larry said in a low voice. “I had a fear that if any story was wrong in any way, there would be consequences.”

“You mean your past.”

“Someone would go right to my illness. Always, I was looking over my shoulder.”

“Were you a tough critic?”

“I demanded exacting standards of writing for myself every day. I think I had to work harder than anybody else just to satisfy myself. I did not want to compromise my credibility. I built a network of people I trusted and who trusted me, and that worked.”

Those of us who fight illness battle on two fronts. We fight both the disease and public ignorance. That survival mechanism minimizes new wounds but does not hide the scars. Larry needed a more personal connection.

“I WAS ALONE because I was not worthy of another person. I really did believe that.” Larry’s lithium weight gain only accented his loneliness. “That was one reason I became even more reclusive, at least until Grace came along.”

Larry’s wife Grace was working as an advocate for the developmentally disabled in Georgia when they met. “I was just as much drawn to her life values as to the fact this was a beautiful woman,” Larry explained. “You have to connect on the big issues. In the end, that is more important than anything else.”

Grace offered the same sentiment. “It is the values that keep people together.” Then she began to laugh again. “Hey, wait a minute,” she shouted. “We are regular people, you know. We like food. A lot. We love the outdoors, our dogs. A lot. And Larry is very funny.”

What Grace was speaking to is a curious misconception about any couple living with a chronic illness. Folks seem to believe that illness dominates dinner conversation. “They think the illness is the center of everything,” Grace observed, “but it is not.” You mean there is more to life than being crazy? “Look, Richard, we talk about policy issues or workshops or books we have read on the general subject, not Larry’s specific illness. We also talk about movies and art and what we read in the paper this morning.” I totally understood. It’s not as if Meredith and I sit around talking about degeneration of the central nervous system!

The frustration in Grace’s voice was evident. “What people believe about mental illness and about someone sick can be worse than the disease itself.” That statement echoes from Larry as well. “I was put in this diagnostic box and could not get out. If I get excited about anything, people say, ‘No, that is a symptom of your illness.’ If I get upset, ‘No, this is your illness.’” Larry’s emotion now was apparent. “When does the diagnosis stop and the human being regain a sense of control of a life?”

I WAS IN a taxi headed for a generic motor lodge on the outskirts of New Haven where I was going to watch Larry work. Even though I knew him well and felt comfortable in his presence, I felt slightly ill at ease.

This morning, I would sit surrounded by individuals, real people, who suffered from debilitating mental illnesses. This would be a field trip for me to watch and listen. Larry would be running training sessions, teaching the seriously sick to help one another and, of course, themselves.

The cab pulled off the busy highway and onto an access road as trucks and buses and assorted maniacal motorists screamed by. Soon we were in the parking lot of the least charming place I could imagine. An alienating locale seemed an ironic venue for a gathering of the mentally challenged.

Larry had explained that he and his colleagues believed the mentally ill would listen to one who had walked in their shoes. “They want to hear from each other,” Larry said, “people who have been there and understand. Not some doctor who does not get it.” Larry preaches self-reliance.

I fumbled to pay the driver from the wad of loose singles in my pocket. There was Larry, stout and smiling, standing in wait at the door. We headed for the basement. Participants gradually moved into the windowless conference room. They arrived in clusters. These were regular folks, chatting away, certainly appearing animated. People kept coming in, even as Larry began to speak.

I sat silently, staring and studying appearances and mannerisms. Men and women smiled, going out of their way to be welcoming, even to sit with me. They shook hands and offered more coffee. Many carried pad and paper, and as we broke into small groups, they laid the materials across the tables before them. They were serious about what they were there to accomplish. Many seemed to know one another and were easy with Larry. That comfort derived, quite plainly, from his comfort with them.

“These are people who have lost faith in the world,” Larry told me later. “They are searching for a new connection, struggling to find that faith again.” He thought for a moment. “That is hard work.”

WATCHING LARRY AND GRACE at their cabin-like home in the mountains becomes an exercise in mutual comfort: synchronicity, to be exact. Harmony in the house begins early in the morning, with gourmet coffee delivered to the bedroom by Larry. The man adores his wife.

“I do not know if you are aware of this, but Grace once took over a state psychiatric hospital that was in receivership,” Larry said. “She turned it around with toughness and extraordinary empathy. She really is tough, brilliant and tough.”

Grace also suffers from clinical depression. “I do not know if that is part of our connection,” she said. “I am grateful that it does not bother Larry.”

“But look at his history.”

“Yes, but when you are depressed, it is a downer for everyone around. Even when someone understands, you get tired of it.”

Grace was not on antidepressants or any such medication when she met Larry. “I was worried about stigma,” she explained. “Always. I did not want any evidence around. Larry convinced me to do something about the depression.” He told her she is great. “He kept telling me he loves the total package.”

“Do you think you are mentally ill?”

“Maybe,” Grace answered. “I never thought of that. I guess clinical depression is a mental illness.”

“Are you both better people for that?”

“Without depression, maybe we would not be as empathetic. Maybe we are nicer.”

Larry weighed in. “Grace never experienced the psychosis that takes away your soul. She never had to undergo forced treatment.” Obviously, that becomes its own category, but the stigma applies to anyone who is mentally ill. “Grace does not buy into this stuff that life is over when you are ill.” Larry put up his hand. “Grace just rolls her eyes when people say the mentally ill cannot live in the community.”

With most people, it would seem fair to ask if there were qualms marrying someone with a mental illness. “No,” said Grace in response to that question. “We are soul mates. Our lives do not center on Larry’s mental illness but his mission to de-stigmatize it.” Larry nodded. “When we started going out,” he added, “Grace was less concerned about my mental illness than I was.”

Grace seems unyieldingly proud of their lives, who they are, what they battle. “Richard, let me try to explain something,” she started. “There are a lot of high-profile people in Georgia who have different mental illnesses. So many people know us and Larry’s work. They are encouraged, helped in their lives.” Grace was emotional. “Mental illness to us is a badge of honor.”

Grace and Larry are childless, though not because of concerns about genetic possibilities. “It just happened that way,” Grace said. “I was thirty-eight when we got married. We figured, if it happens, it was meant to happen.” But there seem to be no concerns about passing the illness down. “Not at all,” Grace agreed.

Chronic illness is all about managing. Larry stays away from alcohol because he must, although he watched Grace drink wine with me in their living room with some interest.

“Is it tempting?” I asked.

“Not really,” he answered, “but occasionally I see someone drinking Scotch, and I have to say, it looks good.”

“Do you feel victimized?”

“Not at all,” he answered quickly. “Grace would not let me internalize my issues or become a victim.” Larry smiled. “I am not sure there is a better person in the world for me than Grace.”

Grace is tuned in to Larry. She becomes his muse, taking in his ideas and reacting. “I get excited and get all these ideas. I bounce off of her.” Grace appreciates that role. “We have a great time,” she said. She watches for any warning signals of Larry losing his footing. “I can tell when Larry gets overly anxious or is overtired or working too hard.”

“I had lost the belief in myself,” says Larry. “Grace helped me find that again.”

THAT BELIEF IN self shifted in 1990 when Larry spontaneously went public about his past. The impact of that moment turned him from journalist to advocate. “I was attending a commissioners’ meeting to discuss a community program. The plan was like daycare for mentally ill people.”

Opposition to the project from the local citizenry was strong. “There was a not-in-my-backyard quality to the debate,” Larry said. “People said things that were very discriminatory.” He sighed. “The whole thing was insulting, I thought.”

“Given your own history, you must have felt weird,” I said.

“I was upset and did something very unprofessional,” Larry said quietly. “I told the people there that I was in recovery from a mental illness. I said I had been hospitalized and that the stigma is unbelievable. We have to give these people a chance,” he told the commissioners. “Well, you could have heard a pin drop. They gulped, and then they passed the proposal.”

And an advocate was born.

Larry had been to hell and back and now his spirit soared. “Religion is for people who fear hell,” Larry told me. “Spirituality is for those who have been there.” Life to Larry is not about a church but belief in the human spirit. “Richard, that spirit is why I get up each day.” For him, doctors did not understand this dimension.

“Psychiatry tried to beat it out of me, to convince me this was just a symptom of my disease, a psychiatric disorder.”

“And that was not the whole story?”

“No. Spirituality is different from religion. Even in sickness, I see a spiritual realm that to me is real.” Religion was gone from Larry’s life, replaced by a spiritual sense that tells him to reach out to others.

So Larry was ready for the phone call he received from a state mental health director. Would Larry attend a statewide meeting to set up a mental health consumer network? Larry accepted and became the volunteer coordinator. He and his new colleagues began work on the organization. Larry kept his newspaper day job to underwrite this volunteer work.

His words that afternoon at the meeting in the mountains and his move toward advocacy made a private and highly personal process public. “The term ‘recovery’ is fairly recent in mental health,” Larry observed. “I had to think hard about whether or not I wanted to deal with the publicity, the pain that would go with it.” He went silent. “I had been there already.”

Of course, he could have stayed silent at the advocacy proposal. “I could not break away from the calling,” he said, “but I did not answer them about their job offer for a few days.” He weighed the consequences. “I wrestled with it. I was doing well as a journalist. I could not imagine the passion this would unlock. But nothing I ever have done has motivated me more.”

In addition to setting up a mental health consumer network, Larry volunteered to find a location for a mental health conference. Proprietors quickly backed off when they leaned that conference participants would include those recently out of recovery from mental illness.

Larry’s pent-up anger had a new utility. He aimed it at an ignorant world and at the psychiatric establishment. The imprecision of those doctors, he says, throws human beings into diagnostic containers that may not fit.

“They told me my life was hopeless,” he said, “that I would never get it back. The medical establishment thinks it has the right to take away hope, based on a diagnosis that is, at best, confusing.” The medical profession acts with paternalism, he says, playing an inappropriate role that does not necessarily serve the sick. “I get very angry at this,” he admitted.

And I thought I was the archbishop of anger. Years of MS and cancer had unraveled me more than occasionally. Larry, to his credit, emotes for others. But while my anger can be combustion for its own sake, Larry’s is channeled, generating electricity, which, of course, is power.

“I still have a reservoir of anger that I have to live with,” Larry said.

“Is anyone listening?”

“I do not know,” he answered. “You know, we are dangerous,” he paused, then went on. “They have to silence the insane, the mentally ill, because we tell the truth.”

“I know people who had jobs and may not have revealed they had a mental illness,” Larry said. “If and when they had a relapse and went into the hospital, when they came back, the job was gone.”

“Living with any chronic illness can get you screwed at work,” I said.

“Well, there is a big debate in the mental health community, to disclose or not to disclose.” And? “Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, you do not have to say anything.”

I told Larry I vote for self-protection. He nodded. “No one is immune from discrimination,” he answered. “One of the great stories is about the president of the Georgia Mental Health Consumer Network.” What happened? “He went in to renew his driver’s license. There was a form that asked, ‘Have you ever been treated for a mental illness?’ If you checked ‘Yes,’ they pull you out of line. They also ask about medication. Talk about profiling.” He laughed.

If there is an American prejudice against all people suffering sickness, a special stigma does seem reserved for those who battle diseases of the mind. “The common portrayal of an individual with a mental condition is of a violent person,” Larry said. When a bomb exploded at the Atlanta Olympics in 1996, early newspaper accounts attributed the incident to a crazy person. “The headline always reads, ‘Mentally ill man beats wife.’ You don’t see that with MS.” Fair enough.

In 1999, during the final years of the Clinton administration, Larry spoke to a White House conference where the first surgeon general’s report on mental health was being released. During the meeting, Larry introduced Tipper Gore and spoke of the genetic component in his family’s war with diseases of the mind.

“As a child, I used to sit with my grandmother as she stared at the fire warming her living room,” Larry told the conference. “She would rock and stare, and sometimes an impish smile would creep across her face. I loved her deep, infectious laugh. After giving birth to her youngest child, she experienced mental illness. For all the years that I knew her, no one ever talked about her psychiatric hospitalization, or why she never ventured beyond the fence surrounding her home.”

That Larry had made the journey from the wild experience of mental illness to the White House was lost on no one in the Fricks family. His brother Bill silently wept as Larry spoke.

“What I really regret is that both parents died well before Larry’s recovery.” Bill looked away. “To be recognized at the White House for what you have accomplished…” he trailed off. “All they knew was the pain.” Bill had to pause. “Bless their hearts, both of them. They did not see him come out the other side.”

Before Larry’s White House talk ended, he described the price he paid for his moments of madness. “Never had I imagined that one day I would be four-cornered in the bed of a psychiatric hospital, having people stare at me through a small window in the door.” And then he talked about a place that haunts him to this day.

“When I was a high school senior in Atlanta,” he told the conference attendees, “we took a field trip to Milledgeville. Up to thirty thousand people have been buried on the hospital grounds. We walked through wards and gawked at the patients. I remember feeling ashamed to be intruding on these outcasts of society.”

ARE YOU A man of hope? “Hope is to the soul what oxygen is to the body,” he answered. It was a Saturday night and Larry was heading, once again, to the Atlanta airport, this time flying off to a mental health conference in Australia. “This will be your last shot at me, buddy,” he had warned me over his cell phone, which, of course, was fading in and out. “Make it good.”

As I thought for a moment, Larry kept talking. “Hope to me is the key to recovery. We can encourage hope with practices every day.” How? “I start each day reading something hopeful. I really do.”

“You have lost a lot in your life.”

“Let me tell you, I would change nothing.” That gave me pause. “If you tried to take away my illness, if you could make it just disappear, I would say, ‘No. No.’”

“Strong stuff, Larry.”

“To take my illness,” Larry continued, “would be to remove the meaning and purpose I now have. Mine is a purposeful life.”

“Your illness has overtaken your identity.”

“I was somebody else, a different person before I went through this.”

MILLEDGEVILLE HAD FELT lonely on that September day when Larry and I visited. I remember seeing a marker by the restored gates to the cemetery. An elderly gentleman suffering from bipolar disorder had raised the funds needed to commemorate the spot. He had no known link to the place, no horror stories connected to the facility. And when he died, it had been by his own hand.

A lone figure can be seen in the distance among the graves. It is a bronze angel that Larry and other advocates, all sufferers of mental illness, had donated to Milledgeville. The figure stands as a memorial to the nameless, faceless victims buried all around.

“They may have been powerless in their lives,” Larry observed, “but the message of what they experienced has come through from beyond the grave.” The angel stands in silence. One arm extends up to the heavens, the other hangs limp toward the ground. The circuit is complete.