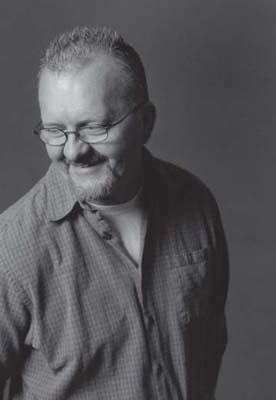

“I AM OKAY,” Buzz Bay said in a shaky voice, blinking away sleep and grinning up at me. The forty-six-year-old man in the bed was gaunt and hairless, the pale portrait of cancer that so many among us sadly see in our own worlds. He had been admitted a day earlier to a hospital in Beach Grove, Indiana, with a ureter painfully blocked by pressure from a malignant tumor.

A white hospital gown was opened at the side a crack, displaying tubes growing from strange places on his body, stretching into various bottles and containers attached to a pole on wheels. The urine output of one kidney trickled out of his body through a rubbery hose he wore out his side.

Buzz had just awakened from a gentle doze, and he was instantly ready to talk. “How was your flight out here?” he asked. “Did you find the hospital easily enough?”

“Buzz,” I asked back, “how are you feeling?”

“Oh, I am fine.”

“Really?”

“Yup. Upright and taking nourishment,” he answered, hardly upright at all. This was not the first time nor would it be the last, that Buzz kissed off that question. As with Denise, a long warm-up had preceded the visit. We had talked numerous times on the phone and exchanged e-mails—words, not intimacy, at a safe distance.

This was not the way I had planned our first meeting. I had been about to head for Indiana to teach at DePauw University when I received a call from the Lymphoma-Leukemia Foundation, telling me Buzz was in the hospital.

Soon enough, I found myself in Indianapolis, speeding south from the airport with my friend from DePauw. We cruised down the interstate, a straight shot of concrete, into the heartland. I was worried. In our recent telephone conversations, the incoming chatter had been weak and without energy, betraying the unmistakable sound of a weary man. Buzz had been in the middle of a chemotherapy cycle, the treatments exacting a terrible toll.

Buzz has non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Lymphomas are cancers that grow in the lymphatic system, an integral part of the body’s immune defense system. As with most cancers, lymphomas take many forms. One type, Hodgkin’s disease, can be relatively benign, with survival rates exceeding 90 percent.

Non-Hodgkin’s, though, is an aggressive and virulent lymphoma. It can be treated but not cured. The chance of surviving five years with the disease is less than 50 percent. This brand of lymphoma struck down activist Dick Gregory, King Hussein of Jordan, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

Still, Buzz has always been curiously upbeat, with depleted strength but an expansive optimism that flies in the face of the facts. I was unsure about meeting him for the first time at his worst, but he encouraged my visit, particularly since I was going to be in the area. Plus, our brief encounter would allow me to meet not just the man but the family. We would all use the next few hours to size up each other.

I was the complete stranger from out there somewhere, a cultural Martian in Buzz’s world. The west side of Manhattan and the rural climbs of southern Indiana are very different lands. Each of us needed the comfort level I had sought and eventually found with Denise. Building that kind of trusting relationship meant bridging a wide gap.

I watched Buzz and watched him watching me. “I like your outfit,” he said, referring to my blue jeans and a sweatshirt featuring a duck. Susan, Buzz’s wife, sat beside him in the small waiting room. We had slowly walked down the long corridor away from his room and roommate in search of privacy. Their son, Ryan, nine years old at the time, sat ducking the conversation, reading and fidgeting, seemingly oblivious to the stranger in their midst.

Buzz seemed remarkably at ease but studied in his responses. He showed a natural talent for deflection, steering the talk away from himself. When are you getting out of here? “I don’t know. When are you leaving town?” Are you okay? “I am here.”

Though clearly in pain and exhausted, he seemed oddly detached from his illness. I had noticed this already. Our deal from the beginning was that he was going to open up about coping with cancer and joining the army of survivors struggling with chronic conditions. Our e-mails and telephone conversations had become routine, however. We were not grappling with the ever present issues of illness, and little of substance had been said. Now here I was, in his face and ready to put the Ping-Pong paddles away.

Buzz looked at me as if deciding his next move. Maybe he was surprised that I had actually shown up, carrying a tape recorder at that. This was sudden and serious, and he seemed not quite ready to let the games begin.

This hairless man had an easy way about him. He seemed to like people, if not what came from their mouths. He was guarded, defended, a shrink might say. His winces were subtle and slight as the questions began. His patter did not vary. Talking face-to-face at last, making eye contact, may have seemed threatening. I felt the awkwardness of the moment, too.

Buzz seemed determined to appear confident or at least comfortable with his physical condition. He clearly was exhausted and in pain, surrounded by a family that seemed bewildered. But there he sat, dispensing limitless cheer. Throughout the afternoon, the guy smiled and quipped and never seemed to walk off the stage. He was playing to the audience. Me. The jokes were the giveaway.

“How are you?”

“I woke up this morning. That’s good.”

He had his routines down. Even as Rome was burning, Buzz was playing the fiddle. Buzz, I would learn, is a naturally sunny and optimistic fellow. His glass is forever half-full. I do not want this to happen, the emotional reasoning goes, so happening it is not.

The ring is familiar. Dependable denial had formed the architecture of emotional survival for me, too. My denial was rooted in pushing away realities I could not bring myself to embrace. I could dance the two-step, revising any prognosis with the best of them. Denial kept me going. That talent can be a strong ally, a healthy coping mechanism, depending on how smartly it is applied.

If denial kept Buzz from clear and sensible thinking, that would be quite different. It was too soon to know, but the bright outlook seemed to be out of context, if not out of touch.

Beyond the quips, Buzz did make one fact, perhaps the most far-reaching about his life, strikingly clear. “I have a belief in God, a trust in my heart.” He was going on the record. “You cannot see faith, but it is there,” he said. “Our lives are built on that faith, and someday, our faith will take us to another level,” he told me as I left the hospital. That belief system is stitched on every sleeve in Buzz’s modest closet, even on his stained hospital gown.

A devout Christian, Buzz has beliefs that are ironclad and unshakable. “One way or another, I will be cured,” Buzz would assure me repeatedly, “here on earth or in heaven.”

That single assertion said it all. The faith game was new to me. Alien. But I was committed to listening.

FOUR MONTHS AFTER our accidental visit, a more ambitious itinerary and focused plan carried me back to Franklin, Indiana, the town where Buzz grew up and now lives with his family. Franklin is a small island in a sea of corn and soybeans, sitting twenty-five miles south of Indianapolis. The town is home to twenty-five thousand residents. There is an eerie order to the place. Houses are well kept and neat, the lawns manicured, the streets quiet and clean, really clean.

For a New Yorker, a small town in the Midwest was unfamiliar territory. Franklin was out of a coffee table book. The folks are mostly white, and they all seem to be smiling. There are churches on every block, planted and sprouting up next to each other like crops. This was 1950 in the new millennium. The Cleavers could have lived here.

The Bay home, an 1890s wood-frame farmhouse outside town, sits on a small road at the end of a crooked dirt path. There is a warm, homey feel to the old place. Odds and ends of a family’s life—toys and shoes, books and magazines, stuff—lay on the floor in every part of each room. Buzz, Susan, and I settled into comfortable worn furniture.

Buzz appeared to be much improved from the hospital, his furnace rekindled. The tube draining his kidney had been removed two months earlier, after a scan indicated that the tumor blocking the flow of urine had shifted away. The painful pressure on his ureter was gone.

He seemed to have recovered, albeit temporarily, from the siege suffered during my first visit. He was a new person. He seemed relaxed, had put on weight and grown a head of hair. He was even more confident and cheerful than before.

Still, my “Hi, how are you?” was met with a smile and “Upright and taking nourishment.” New man, old material. An easterner’s caricature of the Man from Main Street, Buzz appears to have stepped right out of a Jimmy Stewart movie, the straightforward standup guy utterly without guile, no rough edges. I kept prodding and poking, teasing and testing to see what he was concealing behind the smile. But the smile never disappeared.

Buzz and Susan have been married for twenty-five years. An attractive woman with an open face, this straightforward lady has a comfortable air about her. When Buzz went into his routines, she patiently chuckled and sighed with affection, almost rolling her eyes.

“You know Buzz,” she would say, a common phrase in their circle of friends. Susan makes the family train run on time. She exhibits an understated resilience and is there for Buzz, without folding her identity into his. Just like Meredith, she can take a step away and call her husband on how he deals with his emotional health.

The two had met in junior high and were a couple through high school. Buzz went on to attend Johnson Bible College in Tennessee, while Susan studied nursing in Indiana. They were married in 1982. “Susan was the only one who would put up with me,” Buzz said, laughing. “I always knew she would be my wife.”

The couple adopted Ryan in 1995, after years of attempting to start a family. Buzz approaches parenting with the energy and enthusiasm of an adult who feels just plain lucky to have a child. The Bays are an inseparable three-some. Whither thou goest, they go together.

Buzz and I were getting serious when he remembered he needed to run a quick errand. We drove into town and circled the square, looking for a parking spot. What would take an hour in Manhattan took only a minute. Buzz was in better humor than I, as he walked and I stumbled down the street on this morning. He nodded to and greeted everyone we passed as if he recently had been elected mayor.

At my urging, Buzz cheerfully began describing his journey into illness, a tacky tale of missteps and miscues by his doctors. This had not been medicine in its finest hour. Buzz is a generous man, a true Christian who lives it as he sings it on Sundays. His equanimity did not crack as the story unfolded.

His journey into the medical maze began with a nagging case of athlete’s foot, one that simply would not go away. “I am not an athlete. I tried different medicines and ointments, and it just kept getting worse.” He laughed as he told me these facts, as if they were funnier than far-reaching. His voice did turn tense, though, as he continued.

“Then my family doctor said, ‘There is a new medicine I want you to try, but I need you to take liver tests to make sure you can take it, because this medicine is very strong.’” The blood work came back with ambiguous and troubling results. An ultrasound, done at the same time to determine if the liver was enlarged for any reason, showed shadowing around the organ. That was not a good sign.”

For Buzz, this all sounded routine. No one chose to suggest otherwise. Amazing, I thought. Is “paternalistic” a more accurate word? When colon cancer had come my way and tests got goofy, I was told what was happening in painful detail. Most doctors long ago stopped turning lights off on patients.

“Everyone in the office knew that something seemed wrong but us,” Buzz remembered. “The entire staff in the ER where this was done had seen the results. They knew the story and, besides, they knew Susan well. She works as a secretary in the emergency room at the hospital. That is where all this was being done, so we knew everyone.”

This sounded like a conspiracy of silence. “Well, the privacy laws forbid unauthorized disclosures by medical people,” Buzz said.

“Come on, Buzz,” I said back. “These were your friends. They could have said something indirectly or sent a signal, grabbed an imaginary noose around their necks or whatever without breaking the law.”

“Maybe they thought I already knew,” Buzz suggested, turning the other cheek. “They asked me to take a CT scan.” Still, Buzz saw no evil and asked no questions. “They made it sound like, no big thing. You are over forty. We just want to check things out.” Buzz just did what he was told. “I thought, well, okay, I guess this must be no big thing.” To anyone else, of course, a CT scan suggests that something might be very wrong. Doctors let Buzz think otherwise.

The scan was done. Doctors saw a mass on the screen. “‘You know, this could be nothing,’ the guy told me. ‘Men over forty sometimes get these benign masses and they go away, and sometimes they are nothing at all. So don’t let it worry you.’” That it actually could be something never entered his mind.

For me, suspicion starts with the word “sometimes,” especially when uttered by a doctor. That word is a communications cop-out. “The doctor just did not want to worry us until there was something to worry about,” Buzz said. Right.

The CT scan was rushed to Indiana University Medical Center. Specialists immediately reported back to the local doctor that the scan had determined the mass was malignant. Now there was something to worry about. Buzz still was told nothing. “Well, see, there was a mix-up at the doctor’s office, and no one told us.”

The cone of silence had dropped over the Bays. “The doctors were supposed to call us in and explain everything.” Instead, “They just asked, ‘Can you come in tomorrow? We want to do another scan of the mass, this time with a needle biopsy.’” Buzz did not know why the doctor wanted to repeat the procedure, and the doc was not talking.

Buzz ducked into a shop, and we headed home. He was making small talk again and staying on safe ground. He made tea. We sat around the kitchen table with Susan, who picked up the story. “We said to each other, ‘This is kind of strange,’” she said, “but no one ever explained anything to us.”

I could only wonder why Buzz and Susan were not running down the corridors by then, screaming for information at the top of their lungs. If an impending procedure seems “kind of strange,” isn’t it time to start asking why?

“Cancer was not even in my mind. I did not think anything about it,” Buzz said again. Please, Buzz. “Look,” he said gently, “I had such peace in my life. I just was not worried about it. I was very laid back.” Got it, I thought. We do live on different planets. Peace is one thing, a blind eye to the truck bearing down on you is quite another.

Susan, who had studied nursing, might have known better. Opting for ignorance over information seemed so odd. Maybe this was homegrown emotional pain management. Doctors routinely prescribe strong medications for searing physical pain. We are grateful for that numbness, however temporary. Even short-lived denial can provide the same kind of palliative care, blunting emotional pain. Physician-assisted denial is legal and seemed to have been at work here.

Finally, Susan did open her eyes and realized there were blinking red lights in her face. “Something is not right here,” she said to herself. Buzz caught the vibe. “I could tell she thought something was wrong.” The subtle sense that something was amiss came less from the quality of the information than from the faces and body language of friends and colleagues. The sunshine had vanished.

“When we went in to the X-ray department, the whole mood had changed,” Buzz continued. “No one would talk to us. Everybody was really aloof. They put us in this room by ourselves, which they had never done before. My sixth sense told me something was not kosher.” Buzz still had not assumed the worst.

“It was the looks on their faces,” Susan recalled. “I knew these people. Something was really wrong.” Then she laughed softly and dug herself in deeper. “When we saw pictures from the first scan, you are not going to believe this,” she said.

“What?” I pressed.

“We thought the mass was an extra kidney.”

Even when danger is sensed, there can be pockets of adamant disbelief. Buzz’s denial must have been contagious.

All came clear as Buzz was being prepped for a needle biopsy, a painful stab in the belly performed under a scan to guide the needle. The radiologist entered the room and asked if their family physician had talked to them. “I said ‘no,’” Buzz remembered. “‘I have not heard from anybody.’” There was a moment of silence. “The doctor realized we had no clue, and I will never forget the blank look on his face.”

The doctor stood, staring at the Bays. “‘You have no idea what you’re facing, do you?’” Buzz recalled him saying. Buzz was bewildered. A moment passed. “‘What you have is non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and you have a malignant tumor in your belly,’ the doctor said.”

This moment of truth came on August 11, 2001, at eleven o’clock on a sunny Indiana morning. Buzz thought the scene was strange. “Funny” was the word he used to describe the moment. He also thought it strange that the memory was cemented into his mind. Odd would be if that recollection faded with time.

Buzz had talked before about the loneliness of illness, which I have decided for myself is unavoidable. The feeling of emotional abandonment by physicians, the very people who should be counselors as well as care providers, can be devastating. When that happens, a rapidly increasing sense of isolation is inevitable. I asked Buzz if he felt that. “I am afraid so,” he answered. “I felt that Susan and I were left there to figure things out for ourselves.”

Emotions came quickly. “My wife started crying. It was like I heard just sobs.” Buzz stopped talking for a moment. “It was that weird moment. You hear it, but you really do not believe it. I said to the doctor, ‘You said what? How can athlete’s foot turn into cancer? I do not understand.’ I was stunned.”

“What else did you feel?” I asked.

Buzz had his answer at the ready. “Then I figured that when you are given lemons,” he said with that smile, “you make lemonade.” Great, I thought.

“That’s it?”

Buzz only shrugged. A reality sandwich and a chaser of lemonade. Buzz had turned the other cheek so far he had performed a three-sixty.

Buzz was characteristically charitable, not angry, just quietly disappointed with the way he was treated by his doctors. He laughed self-consciously, ready to change the subject and move on.

“We were going into this completely blind” was his low-key complaint when I would not switch subjects.

“Did you say anything to the doctor?” I pressed.

“I said, ‘This was a monumental crisis and decisions that we were going to be facing here, and not even to be told…’” Buzz responded, trailing off. “‘Well, it just slipped through the cracks’, is about all he said. ‘That is a big crack to fill there, buddy,’” Buzz had answered.

“You sound as if you do not like doctors very much, Buzz.”

“It’s hard when they do not respect you,” he allowed. His reliance on physicians might have tempered his willingness to blow his cool.

“Buzz, do you get angry at anything?” I asked. I could read the sincerity in his expression.

“Sometimes I do hurt” was all he would say.

We have no concept of what to expect when illness comes. Vulnerability seeps from our bodies like a slow bleed. The quality of our connection to a trusted physician becomes an emotional lifeline. We lean at different angles and with varying degrees of force in our search for support.

When our heroes in white falter beneath our weight, we struggle to stay standing. Asked if the way he was handled by the doctors just added unnecessary emotional pain, Buzz looked at me as if that was about the stupidest question he had been asked. “Yes,” he said with no embellishment.

WHEN PEOPLE HEAR the bad news, their reactions are as distinct as their personalities. Buzz’s first reaction was shock, followed immediately by a joke. But in time, his attention shifted to others. “My caring instincts took over, and I just wanted to make sure my family and everybody was okay.” For him, family and close friends, had to come first. Thoughts for himself and fear of the future were not on his radar screen.

Then he paid a visit to his church. “My minister told me to stop and allow what the doctor told me to sink in. ‘What you do and feel at this moment will be your witness for the rest of your life,’ he said. So I asked to be left alone for a minute.”

Only one minute to contemplate and plan the rest of his life? “Not really a minute,” he answered. “I was alone for a while. I needed to get myself together, to think. I prayed. I was asking God for help.” He took a long breath. “I said, ‘We will be in this together.’”

I wondered what Buzz thought his minister meant by What you do and feel at this moment will be your witness. “He was telling me that how I present myself to other people in this moment of crisis, what I do with it, will define me.”

“And are you at peace with that?” I asked.

“Yes. I am not a negative person. In fact, I think I stay pretty positive.” This may explain his concern for others around him, even his cheerful face for all to see. If Buzz believes that at the end of the day he will be judged by the quality of how he handles his disease and perhaps death, his path is clearly marked.

I, too, have known the quest for grace in the face of sickness. The prospect of death for me remains distant, and my search has been secular. As far as I know, God has not chosen to hang out in my room. I can hear Buzz now, smiling and telling me, “Yes, He was there.”

When I learned that I had multiple sclerosis and later cancer, there was a cacophony of silence in my head: the sound of nothing. One doctor suggested that my emotions ran the gamut from a to b. I am still listening for the telltale sounds of high emotion.

Buzz seems not to indulge in such emotion, either. Conduct in the face of illness is an intensely private negotiation with self. Going forth with grace is important to both of us. Buzz attaches a different meaning to grace. “God’s grace is his magnificent, overwhelming love. Grace covers us.”

In my world, grace goes in another direction, defined by an individual’s conduct. Grace becomes doing right by others, those we care most about. Grace is my gift to them. Grace means doing it well. A graceful exit, for example, means giving the journey your best moves.

Buzz also gives to others, in far greater quantity than he gives to himself. For him, assisting the next guy comes at the expense of his own emotional needs. The two are not mutually exclusive. I have experienced pain and suffering from illness and sought to find my way across myriad quality-of-life issues. I love my family, and want to comfort them. I believe that I give to others but I also want to take care of myself.

Fasten your mask first, the flight attendant advises grown-ups. Then take care of any children. Survive so that you can assist others. Threatening illness demands a period of self-absorption so that, afterward, we can help those we care about. Buzz was busy conspiring with the Lord, trying to figure out how to tend to the needs of everyone else. The mission of a devout Christian was well defined for him. He did not question what he had to do.

Buzz’s moments alone on that day of reckoning produced this plea: “I asked God to make me, with whatever time I have, be a strong witness for him. Allow me to give other people hope when there seems to be no hope.” He went on, as if preaching. “Help me to be strong for Susan and Ryan and just try to be the best husband and father that I can be.” Finally, he added: “Help us as a family to fight with all that we have against this, and know that we did the best we could.”

That was the first call to arms I had heard from Buzz. And then he tacked this on: “And allow our family to help other families to know that God is there no matter what.” He paused. “I know it sounds hokey, and I have never told anyone about that moment, no one.” Why? I asked. He laughed self-consciously. “They would think I had gone off the deep end.”

Many newly diagnosed patients do wander close to the deep end. Panic sets in. The path becomes blurry. Not so with Buzz. He took matters straight to the top. He was getting the situation wired with the Lord. By now in this conversation, Buzz had stopped chuckling. “Besides,” he continued, referring to his pact with God, “it was private.”

“What next?” I asked.

“I made sure everyone was okay, including the minister and the doctor.”

“The doctor?” I asked in astonishment.

“Yeah. This was the radiologist who had to break the bad news, and he was not supposed to be the one to tell us. Our doctor had not done that.” So, patient tended to doctor. “He said, ‘Stop, Buzz. Let it sink in. Let yourself be angry.’ I could not be angry. I simply told Susan, ‘God and I have talked.’” Case closed.

BUZZ’S MEDICAL ODYSSEY picked up speed immediately after his diagnosis. The day after getting the bad news, he was at the Indiana University Medical Center in Indianapolis, meeting with an oncologist he would come to respect. Though Buzz’s assorted earlier physicians had dropped the ball, this oncologist picked it up with sure hands.

“Boy, she was marvelous, smart, kind, caring, and very beautiful, by the way,” Buzz said, adding, “and that was the fastest I have ever gotten my clothes off in my life, and she did not even ask me to.” The doctor offered comfort and hope to the Bays. She built a relationship with the family that endures, though she has moved west.

The doctor immediately extracted bone marrow from Buzz’s hip. “That was the most painful procedure in my life,” Buzz recalled. “I bent the bed rail, it hurt so badly.” Susan had been encouraged to hold Buzz’s hand, because of the pain. “‘No thanks,’” Buzz said Susan remarked, “‘He will break it.’”

The procedure was vitally important. “This was to see if the cancer already had invaded the marrow,” Buzz explained. “It had not. That is a good thing.” And then? “Nothing.” Buzz went through a slow-motion period known as watchful waiting. Doctors stand back and wait, monitoring the tumor until something happens.

It was a game of human chess. “The doctors wait for your body to make a move. Then they move. This was the worst time.” In the Bay household, imaginations ran wild. “It sucked, because whenever you felt anything, you wondered if it was the tumor growing. If I got a cold or anything, it was, is this the cancer?”

The nerve-wracking period lasted six months. In April 2002, a CT scan revealed that the cancer had become active. The tumor was growing, invading Buzz’s lower abdomen, between his spine and small intestine. “It had grown to the size of a baseball,” Buzz said. The docs put him on the drug Rituxan. “The tumor shrank down to a little bigger than a golf ball.”

The drug did not do much to alleviate the pain. Buzz explained that his tumor was free forming, meaning it was unattached and could move almost anywhere. “The pain is sporadic, but the mass can be extremely painful when the tumor shifts and hits my spine. I just learn to live with it.” Too frequently, that is the story of chronic illness. Pain becomes a small price to pay for survival.

“I do have pain medication,” Buzz explained. “I do not like to take it because of the side effects, feeling woozy, you know, not very sharp.” He takes acupuncture treatments when the pain is intense. “Usually, I just grin and bear it,” he said with a broad smile.

“In May of 2003, I got horribly sick on Mother’s Day,” Buzz recounted. Now the guy had shingles. Shingles is herpes zoster, a painful rash that produces an intense burning sensation in the skin. Shingles is frequently triggered by chemotherapy as well as stress, and the pain can be debilitating. In the summer of 2003, a scan indicated renewed growth of the tumor, which meant more chemo. “This was bad,” Buzz said. “Shingles came and went, and my hair fell out. I was sick, really sick.”

Buzz is as decent a man as I have ever met. He practices his beliefs through the six days that follow Sunday. He is immersed in the word of the Bible. More than occasionally, I have thought of the Book of Job. This book of the Old Testament asks why, if there is a God, the innocent should suffer when at the same time the wicked escape and are permitted comfort and prosperity.

“Buzz, are you familiar with the Book of Job?” I asked.

“My goodness, yes.” He laughed. “At church, they call me the modern-day Job.”

“Do you believe you are being tested?”

“Yes, I do. Very much so,” he answered quickly. “This is all about how you deal with it.” He paused. “God never gives you more than you can deal with. Faith is always tested.” Those tests continued, hitting Buzz from odd angles.

After my visit, we did not speak again for a few weeks. Then an e-mail from him popped onto my computer telling me that he had just been released from the hospital. He had gotten violently ill in the restroom at church. Susan had taken him home. “Then I got so sick, Susan rushed me to the hospital. I kept passing out. The doctor felt I could have had a mild stroke. I do not even remember Monday or Tuesday. My doctor came in and said she had not seen anyone so sick in her career.”

When I called Buzz later, he told me his blood counts had suddenly bottomed out for no reason. He had been knocked out for a week, but finally was released and walked out of the hospital. It was a mystery. “I bounced back. It all comes down to the F word. ‘Faith.’ I prayed my way through.”

The tumor was growing, and a week after the hospital stay, Buzz began radiation therapy. This wounded man would endure a total of twenty-eight rounds of punishing radiation, beginning before Thanksgiving. “I did not know what to expect,” he told me during a subsequent visit as we drove around in his old van. This was high-tech torture. He lay in a sculpted form to prevent him from moving. A piercing buzzer sounded if he shifted even slightly.

“They put blue marks on my torso as a map.” And? I asked. “I got burned, like a bad sunburn.” The radiation did help. “It shrank the tumor some, but not as much as the doctor wanted.” Buzz reacted violently. Treatments were relentless, concentrated in the lower belly, where nausea forms. “Gosh, I was very sick. They were cooking me.” The vomiting would not end.

Buzz learned practical precautions to minimize the violent reactions. “Yeah, the hard way,” he said. “You learn to eat very lightly. Usually, I ate about five meals a day. And I would sit down and just rest, just sit in a chair and not move. That was good.” Cumulative pain and puking from chemo and radiation pushed him to a mind-set he had so far resisted: He felt like a victim.

“I had no options left. Seeing yourself as a victim does not feel right.” The man’s life was so miserable that he did consider, albeit briefly, halting treatment altogether. “The thought rested in the back of my mind,” he admitted. “My goodness,” he added, “this is not quality living.”

“All along, doctors keep telling me the disease is incurable,” Buzz said, “so why are we doing this, I mean, what is the point? I asked if he had resolved his urge to quit. “Not really. The thought never leaves the back of my mind.” Buzz said his doctors had made clear that they would respect whatever he decided.

Buzz came to know the common emotion of many cancer patients. “I can see why people commit suicide. Pain and despair are so strong,” he said long after his treatment ordeals. “Not me. I knew that in the end, faith would get me through this and make me stronger.”

But God did not end the cancer or the pain. “No, but I found strength, and for me, that is proof that God is alive.” As an article of faith, Buzz had to keep going. “We have an obligation to live that is moral and religious. We must keep fighting.”

I have been prescribed drug therapies for MS that bring on far less pain and discomfort than Buzz’s. There are side effects, however, and I believe those drugs did little good. There was the strong temptation to quit. So I did quit, but only after years of telling myself, You never know. “That is it,” Buzz exclaimed. “Maybe in some tiny way I will be better, and it will be worth it,” he concluded. Then he added: “Maybe it will make the end easier. Just keep me comfortable and let me live the rest of my life.”

I had not been thinking in terms of death, but Buzz’s eye seemed focused on a spot that lies beyond his painful horizon. “Richard, heaven is going to be great.”

“Buzz, I am not convinced we are headed in the same direction,” I responded. “It may be warmer where I am going.”

Buzz chuckled back. “You never know, Richard. You still have time.”

However reluctantly, Buzz committed to continuing treatment. But he took a break. Thanksgiving and Christmas were fast approaching, and he did not want to be bothered with torturous treatments for a while. “I wanted to at least feel human again, to have some feeling of life and purpose. I did not want to put Susan and Ryan through so much confusion, you know, trapped on this roller-coaster ride.”

Despite Buzz’s wishes or wishful thinking, Susan and Ryan indeed are strapped in and along for the wild ride. With any serious chronic illness, families are sucked into the maelstrom. Meredith has often said in frustration, “This is not Richard’s MS, it is our MS.” There is no way to shield loved ones from the pain.

ON A FRIGID March morning a few years later I drove to Ryan’s school near the interstate. A dusting of snow added shivers to the short ride to the outskirts of town. I had told Buzz I would be happy to talk to Ryan’s classmates, many of whom were publishing little books in their third-grade classroom. The youngsters sprawled on small chairs, wide-eyed and focused. This was a guy from the big time, they had been told, and I was having a good time pretending that was so.

Even as various young students leaned forward in their temporary roles of aspiring writers and asked what it is like to write a real book, Ryan sat back, appearing disengaged. Kids shared their book ideas, some showing me what they had produced. Topics were age-appropriate, light-fare tracts about grandparents or sports. Buzz already had filled me in about Ryan’s book.

“One day, Ryan came home from school and said he had something to show us. I thought he had gotten an F,” Buzz remembered. Instead, Ryan presented them with a small, brightly colored, carefully illustrated book. The slim volume had been simply bound and self-published in his school.

Daddy’s Adventure was Ryan’s carefully crafted Book of Daddy and Cancer. The Bays had taken to referring to Buzz’s anxious trips to the emergency room as his “adventures,” hopefully easy listening for Ryan’s uncertain ear. The concept stuck. The idea for the book had come from the boy himself, with encouragement from his teachers, but without the knowledge of his parents.

“I wanted to write about something I was feeling,” Ryan had explained to his parents. “There are other kids with sick parents. Maybe this will help them.” The book offered Ryan’s take on Dad’s disease. “Daddy and Mommy said going to the hospital is like an adventure,” the book read. “When we see the oncologist, try a new drug, or have to stay in the hospital, it’s like an adventure, something new and different to experience.”

Daddy’s Adventure is a child’s attempt to demystify cancer. “Yes,” Buzz said decisively, “it opened a whole new comfort zone for Ryan, that cancer was okay, that it did not necessarily kill you.” Buzz was speaking with ease, as if in his own head he had worked this through. “You can live with the word ‘cancer’ or die by it, and together we have chosen to live.”

Buzz and Susan had decided to speak openly with Ryan about Buzz’s dealings with the disease. Meredith and I traveled the same road with our children, in the belief that full disclosure would foster security for them. I assumed Buzz had explained his belief that God is there for him and wondered if Ryan would stray far from his father’s calming faith.

Faith in the face of illness continues to be a mystery to me. The belief that beyond the limits of medicine, God will take care of the rest involves an alchemical assumption spun from denial and faith. That confidence and the sense of peace it inspires reside deep inside the Bays as a family.

Buzz and Susan thought hard about what they were going to tell him about the cancer. “Ryan sat outside with us, quiet and attentive. That was very rare.” Buzz laughed.

“I explained, with Susan on the other side, that I have a tumor and the tumor is cancerous. Ryan never cried. He asked if I was going to die.”

“What did you say?”

“If it is my time to go to heaven, I will go and, I will be that angel on his shoulder to protect him. That seemed to work for him.”

Buzz and Susan wanted Ryan to be prepared, not scared. Instinctively, the couple understood there is no alternative to the truth. “We explained everything,” Buzz said, “and he knows where parts of the body are.” They even told Ryan about the trouble spots.

“He knows what my blood levels are, and what that means. Ryan understands what a red blood cell is, what white blood cells are. He knows all that.” Susan added, “We talk about the treatments and that sort of thing, and of course he sees Buzz sick. Ryan does see it, and he gets it, and that is good.”

Ryan had been down this road before. Buzz’s best friend, Mark, had been diagnosed with stomach cancer only the spring before Buzz’s diagnosis. “That really bothered Ryan,” Buzz explained. Mark was Uncle Mark to Ryan, who visited the trucker at home and in the hospital, laughing and crying with him as he deteriorated and died.

Ryan sees Mark in his father’s suffering. “Oh, yes,” Buzz said. “Ryan will see me sick and ask, ‘Daddy, do you think you will go like Uncle Mark?’” Buzz remembered Mark’s death as beautiful, but hard on Ryan. “Ryan sat in Mark’s lap the day before he died. “‘I will be watching you from heaven,’ Mark told him. Ryan still brings that up.”

Buzz believes that Ryan’s calm adjustment to his cancer did not connect to reality until the boy came face-to-face with cancer’s brutal side effects. “The cancer did not register until he saw me throw up over and over after chemo and radiation. I was violently sick.” Reality was reinforced when Ryan discovered Buzz collapsed in the church bathroom one day.

“He was so calm when he went for help that some folks did not believe him,” Buzz recalled. “Ryan is very mature now. It makes me sad. He has had to grow up so fast. Cancer has been a part of his life for the last four years.”

What we see on the outside, I have decided with my own kids, is not what you get deep within. Ryan’s ordeal had to be more searing than Buzz could know or, perhaps, handle. Seeing his father’s collapse in the church bathroom had to frighten Ryan.

“Susan and I talked to him and explained that Dad will get sick sometimes, but that the medicine helps him get better.” Buzz believes that getting his son involved made a difference. “Ryan would read to me as I lay by the toilet with a pillow and blanket. He would be comforting me.”

Buzz recounted one particularly bad bout that seemed to push Ryan over the edge. “Ryan flew out of the bathroom crying, ‘Daddy is dying,’ and he did it very loudly,” Buzz said. “Ryan really was scared.”

School counselors assured the Bays that Ryan was dealing with the family crisis well. Ryan’s even keel could be temporary or just the boy playing to the audience around him, I suggested. “Handling the cancer well has stayed with him,” Buzz answered. I was not convinced.

During my final foray into Indiana, I wanted to sit down with Ryan to talk about the cancer in his family. Visits to the old farmhouse up till then had been casual and pleasant. Susan and Buzz knew of my interest in talking to Ryan. They agreed without hesitation. Not yet, I would tell them.

I had established, I hoped, a reasonable comfort level with the youngster. I wanted to wait for a moment when the boy was at ease, the conversation not forced. Ryan went along for the ride as Buzz and Susan picked me up at the airport for that visit. We pulled into the Bays’ driveway and into the old garage. As soon as the car stopped, the boy was gone.

Buzz sat on the worn couch with me, patiently waiting. Eventually, Ryan came downstairs and sat on the floor at his dad’s feet. A GameBoy was clutched in his hand. Ryan and I made small talk for a while, and then I tentatively began.

“Ryan, do you remember when you found out your dad was sick?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Can you tell me what you remember?”

“Well, them telling me about it.”

“What was that like?”

“I don’t know.” Ryan stared down at the GameBoy.

Already, the conversation was difficult. “Was it pretty scary?”

“Yes.”

I looked down toward the floor. Ryan looked as if he was going to jump out of his skin.

The love in the Bay family is obvious. But Ryan seemed freaked, and Buzz needed to believe that the boy was just fine, that the cancer was not eating away at at him, too. I dropped the subject.

IT WAS 3:00 A.M. on an April day in 2005 when Buzz awoke, barely able to breathe, turning blue and struggling. “This was the first time Susan was truly scared,” he recalled. “As we were going to the hospital I remember hearing Ryan say over and over again, ‘Breathe Daddy, just breathe.’ Susan called ahead to warn the hospital ER of what was happening so they would be ready.” Buzz was relating the events in a totally unemotional tone.

We had driven by the local hospital numerous times during my visits to Franklin. The building sits just off a busy commercial street in the middle of town. It was not difficult to imagine that night.

“I was pulled from the van and Susan said my clothes were coming off as I was rushed to the trauma room.” Was the place deserted? “Yes, but a great Christian doctor was on that night and never left my side. My stats were horrible, and at one point he did come to Susan with tears in his eyes and told her that there was nothing else he could do, and would she want me to go on a ventilator? Susan said that was the worst night, knowing that I might die. And there was Ryan. How would she tell him?”

Buzz and I were in the car, running errands, as the story unfolded. I asked him to pull into the hospital parking lot. People were wandering into and out of the hospital with no sense of urgency. “Did you think this was the end?”

“I felt like I was seeing everything from above and everything was in slow-motion. It was so strange.”

“So what happened?”

“I cannot explain this, but like magic, my stats got better and my blood pressure came back up.” I could guess the rest. “God must not have thought my time was then. I awoke the next morning in the ICU, wondering, How did I get here?”

“What were you thinking?” I asked.

“I just thought about how amazing God is. How can I use this for His glory? I was not afraid to die at that moment.”

During the summer, Buzz suffered a partial bowel blockage, a byproduct of the radiation. Doctors recommended surgery. Buzz vetoed the proposal because he did not want to be cut, thinking the cancer might spread. Instead, he opted for dependable discomfort until the situation rectified itself.

The doctors raised the possibility of a relatively new procedure, a peripheral stem cell transplant, with cells extracted from the blood instead of directly from the bone marrow. The procedure was less than five years old. The transplant was arduous. Even risky. Patients had to meet a baseline of strength and endurance.

Doctors knew that Buzz was weak and feared he might not survive the procedure. In the end, the decision would be his. He complained later to me about the manner in which the doctors presented options. “This makes me wonder, do the doctors ever talk amongst themselves or do the patients always have to intervene to get everyone on the same page?”

Buzz seemed to object to being offered more than one option. “Yes. Why can’t they agree and just tell me what to do, what the treatment should be?” More proactive patients want options laid out, with an assessment of the upsides and downsides. These patients demand to be part of the process. Buzz wanted to follow orders, not weigh recommendations.

Finally, he was told in no uncertain terms by his trusted oncologist that a stem cell transplant would not be an option. “The doctor said I would not survive it,” Buzz said, sounding peculiarly matter-of-fact about the whole thing.

“And that was it?” I asked. “No second opinions or further research?”

“No.”

Some of us in the land of chronic illness object to rigid doctors who say it is their way or the highway and who insist on quiet compliance. Other patients resent having to weigh in on decisions that seem beyond their medical expertise. They show no interest in making decisions and prefer to follow orders by the experts.

Buzz does both. “Some oncologists get you, and it’s like, it’s their plan or no plan. They will not waver. This is what you are doing, and, no, you cannot do that.”

Buzz claimed he had been aggressive, sampling unorthodox treatments and had to duck when he told the docs.

“I have met a couple of doctors who were like, well, why did you even try that?” It was the condescension that offended Buzz the most. “One just said, ‘That is just a stupid old folks’ tale, and who are you to say this?’”

Buzz defended his decision to experiment. “Too many of my friends have had cancer, and some have died. I cannot forget them,” he said. “What the heck. This is my life and my body.” He said a trusted doctor gave him advice he stored in the front of his mind: “Do not ever stop trying. Do what you think is right.”

But Buzz is doctored out. He has decided to accept whatever fate awaits him. “Why be a guinea pig and put myself through all that and miss family time?”

Why not see another doctor and look into options? I asked one more time.

“No,” Buzz answered with nothing in his voice. “I am okay.”

This is cancer, man, I thought to myself. Do not be so passive. Learn more. Doubt. That was unlikely to happen, and to my mind, that was too bad.

Weighing options and participating in treatment decisions is what it takes to become a smart patient, a partner in care. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is a cancer with a menu of therapies. Assorted benefits and risks come with the selections made. I would not leave it all to the doctors.

I kept trying. We were driving through Franklin on a cold November day. I asked again if he could imagine traveling for an additional opinion. “No,” he responded quickly. “Things are fine here.” Passivity allows doctors, sometimes unnamed, to make unilateral life decisions.

THE DESPERATE EFFORT to stay financially afloat in a rising tide of medical expenses is the hidden story of chronic illness. The bills for high-tech therapy and costly medical procedures just keep coming, growing exponentially. At the same time, incomes can drop precipitously as jobs move into the background, taking a backseat to surviving another day after debilitating treatments.

According to a Harvard Medical School study, in 2001, nearly 1.5 million American families filed for bankruptcy, about half of them citing medical costs. Even middle-class, insured families can fall into financial ruin, as sickness explodes and benefits run out.

By the close of 2004, Buzz’s struggle had opened a new front, the battle of the bank. His medical costs were spiraling out of control. And his ill health was limiting his ability to earn anything that could be considered enough. Before long he was seriously in debt.

The new wound cut deep. A traditional man, Buzz found his position as master of the house, guardian of his family, diminished, and his spirit suffered. For him, a long-held passion pointed to a possible solution. Flowers. For decades, he had toiled in the wholesale flower business, working for others but always longing to own his own flower shop. He wanted to become his own boss.

When her husband became sick and sicker, Susan said to him, “Let’s do it,” Buzz remembers fondly. She recognized an opportunity for him to fulfill his fantasy. The Bays had to get beyond the what if? doubts. Susan wanted Buzz to have his moment.

“We bought the building and the business combined. It was a package deal with the bank,” Susan explained. She and Buzz put up the equity in their home and took out a small business loan. They were in.

Buzz’s flower shop was located in Greenwood, Indiana, just north of his home in Franklin. The shop was housed in a large yellow and brown Victorian on a quiet street. “The business got off the ground and flew very well,” Buzz remembered with a smile. The Bays wistfully called the store Forever Flowers.

This small corner of Middle America was awash in colors and smells that belied the florist’s beleaguered state. The bright scented flowers dotting the premises brought Buzz hope. “My spirits were up whenever I opened the door,” he said. Flowers made him happy because they were for everybody and every occasion. Buzz told me, “I used flowers to marry people and bury them.”

“You sound content when you talk about the flower business,” I said.

“Those were great years,” he replied, now characteristically fading into the past tense with a soft sigh.

Eventually the shop had to go. “The cancer got worse and basically took over,” Buzz said. “I could no longer be nearly as hands-on as I wanted. I could not last for a whole day.” Buzz also said that after the 9/11 attacks, the bottom dropped out. Along with everything else, the flower market went soft.

Buzz’s business failure also had to do with loss of control. With good employees, perhaps he could have kept the business going through a dry spell. He paused. “Yes. Maybe,” he answered, but “I could not get everything in the business done exactly the way I would do it myself. I am a horrible perfectionist,” he admitted with a low chuckle.

Just as Denise needed to maintain control when none was in sight and her health continued to crumble, so Buzz couldn’t bear to leave his business in the hands of others, even loyal employees. The Bays sold the business.

A man who teetered at the edge of losing his life lost a livelihood, too. “I felt like a total failure as a husband and father and, of course, provider. It was the worst time of my life,” he said. “I was not able to say, ‘Cancer, be gone.’ I kept it inward, and I felt defeated.”

Buzz cares deeply for flowers, but their colors and fresh fragrance are conspicuously absent in his warm and comfortable home.

“Strange, no flowers for you,” I said.

“They are a luxury,” Buzz replied. “It is like, eat or have flowers.”

For him, the tough times got tougher. “I cannot get a full-time job at this point,” he said. “An employer is not going to want an employee who is always running out for tests or treatments. It is unfair to them, but the whole thing is not fair to us.” Frustration festers in him. “This situation was not our idea.”

Buzz is not bitter that he has long-haul cancer. He is angry about the price tag. “We had planned for our twentieth anniversary to go to Hawaii,” he said. “We were saving, but that is all gone because of the cancer. All our savings are gone.”

Months earlier, a desperate fear for the future had poured into an e-mail to me. “Man, I have no idea where to turn. I have to come up with thousands of dollars and I just do not know where it is going to come from. No one wants an employee who might not be able to work. I have been told that a lot. Honestly, I am afraid for my family.”

Buzz had made no attempt to mask his fear of homelessness. “What if we lose the house? What if I get worse? How are Susan and Ryan going to cope? Where are we going to have to live?” Buzz was learning to fear financial ruin more than the ravages of cancer.

“I am really scared about all of these things. Sorry to dump this on you, but this just keeps building. I lay awake at night just hoping for that miracle, that I would wake up and this was all a horrible nightmare. Susan can only work so much. Thanks for listening.”

Buzz and Susan sought legal advice. “We are working with an attorney to do the bankruptcy thing so we do not lose our home,” Buzz told me in a later phone call. “It is really bad. We owe over five hundred thousand dollars, and that is after our insurance.” A number like that takes a toll on the head. “It plays with your conscience first,” he said. “You know it is not your fault, but I was raised to pay bills and to never live above my means. It is mind-blowing when it happens.”

Just leaning on a support system and asking for help challenge traditional notions of oneself as a man, but in sickness, independence and that male stubborn streak must be relinquished. They do not always go gracefully, though Buzz was grateful to others who could pick up the slack.

Susan’s parents provided a reassuring though limited safety net for the Bays. The ride out to their ranch house on the outskirts of Franklin was pure Midwest, farms and tractors, terrain that stays utterly flat. The wind whipped across the prairie. No hills or buildings were there to stop the mean gusts.

Bob and Dorothy had become a vital two-person rescue squad for the Bays. “Oh, yeah,” Susan exclaimed. “They pick up Ryan for us when I’m working and Buzz is working and stuff like that, and then after work I just go pick him up there. So that helps tremendously.”

Bob and Dorothy’s assistance is at once heartening and distressing. Buzz knows he can turn to them if the bottom falls further. “They would be there for us. I know they would.” The retired couple had greeted us warmly. Dorothy served coffee and cookies. “We are happy to do what we can,” Dorothy said simply.

Buzz appeared uncomfortable. I could hear him gathering his thoughts as we sat at a traffic light on our way back into town. Farm equipment rattled through the intersection, and Buzz had to raise his voice. “I would rather we work things out for ourselves.”

“Going to your in-laws for help would be tough for you, I imagine.”

“It is hard,” he answered. “Very difficult. It is like you are not supporting their daughter as she is accustomed to.”

“No one has complained, Buzz.”

“No, but they had put their trust in me. I feel I let them down.”

Buzz feels compromised as a man, as a father. “If Ryan needs something for baseball, I just cannot do it. That puts a lump in my throat. You are not taking care of your family. That is how I was raised,” he declared adamantly. “Take care of your family, and take care of their needs, and work. Period.” He looked down the street. “I just try to stay alive.”

“Buzz, you are nuts,” I said. “I mean, you have cancer.”

He laughed. “They all would say, ‘You are crazy. This is not your fault.’” The nightmare of unrelenting chronic illness is that pride must yield to survival, no matter how you were raised or what you think is expected of you.

Buzz wears self-conscious vulnerability as a shroud, the burial garment of a man going under. Word of the financial struggle got out in his small community, and the melodrama that followed makes for a good cry.

When the Franklin Daily Journal carried an article about the Bay family battle against non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Buzz’s struggle to survive was reduced to a cliché, a medical sob story. He learned how newspapers portray illness and the public reacts to soap opera on the printed page.

Buzz is not accustomed to wearing a public face. The article reported that he doubted that Susan would manage to make ends meet after his death. “He can’t help worrying how his family will survive financially,” the article read, “worrying that Susan’s job as a secretary at the…hospital will not cover the home payments or medical bills.”

“It was a freaking nightmare,” Buzz exclaimed. He was humiliated by the publicity and offended, he said, by what he considered overstatements. “I am not going anywhere,” he exclaimed. “The article sounded like I was checking out tomorrow.”

He was particularly upset because the reporter focused on the fact that he and Susan already had planned his funeral. “There are certain things I want done, and without planning together, Susan would not know they should be done.” It was as simple as that, he said, and not as morbid as the reporter had made it sound.

The Franklin community reacted with force to the story. “I got forty or fifty phone calls about why we have not been honest about my health and why we closed the business.” Franklin is a village where people apparently either look out for one another or into their windows.

Buzz was reacting to a widening public view of intensely private circumstances in a community that already was manufacturing its own take on the story. The back fence was the local communications medium of choice. True or false, the story had legs.

The Christian community came together to raise money for the Bays. The event was a long time coming because up until then Buzz had very politely turned away helping hands. He was self-conscious about admitting to his precarious situation. Though Buzz was slipping financially, he seemed oblivious to the wisdom of Proverbs, that pride goeth before a fall.

Reality finally set in. “The bills just kept coming,” he said. “Our minister, Larry, sat me down and had a heart-to-heart talk about how many people I have helped and that by not letting them do a benefit, I was robbing people of their joy of giving back to me and my family.”

Buzz swallowed hard and agreed. “It was a strange feeling that night,” he recalled. “People came with tears in their eyes. I felt like it was my wake. All the nice things people said, things that I did not think they even remembered. They were thanking me for changing their lives.”

Buzz was caught off-guard. “I was taken aback by the number of people who came out that night. I never felt so loved. Realizing the number of lives I’ve touched was shocking, to say the least.” And there was a lesson. “Sometimes the smallest of kindnesses goes a long way. God showed me that night that love goes deeper and farther than anything else of this earth.” Maybe we are not as alone as we feel.

The benefit did help. A lot. Harder times would come.

CASUAL STOICISM HAD been Buzz’s close friend. A strategy of not succumbing to high emotion allowed him in his own mind to move forward. He wanted to stay on a higher plain, to remain above the fray. This stance made him seem disengaged from his cancer. It was unclear how aggressively he intended to fight.

Buzz’s brand of passivity either reflected a deep inner peace or belied sheer terror. His silent struggle was known only to him. He claimed to feel no anger, not at the cancer, not with God or his fate. He was even quick to forgive the reporter who created the embarrassing article about his collapsing condition. “I was just disappointed. I do not get angry. I know she wrote from the heart. It was just one of those things.”

There was no anger for the doctor who dallied with the diagnosis and forced his patient to go it alone. “You know, to this day I have never been angry at anyone,” Buzz says. “What is there to get angry about?” I could think of a lot of reasons, but they would fall on deaf ears.

“I think attitude is ninety-eight percent of the battle,” Buzz often said. “Keeping positive is so important. Maybe you can take control of your body with a positive attitude.” He would have no problem finding smart, secular people who believe in the mind-body connection.

Buzz’s insistence on locking his emotions away worries the people in his life. Susan is frustrated by his reluctance to reveal himself, perhaps even to know his own emotions.

“Ryan and I can tell when something is wrong,” Susan told me, “and we want to know what is going on.” It sounded like the taciturn culture that I knew in my family, growing up with a sick and silent father. My old man has MS and actually invented stoicism. At least, that is what I’ve come to believe.

Whatever brews in Buzz’s brain, no cry of “poor me” will pass his lips. He demands that the world see him as what he wants to be, not what cancer has made of him.

“Buzz needs to take care of other people,” Susan observed. “That is part of his makeup.” Selflessness comes to him at the expense of emotional health. “I do not think he takes care of himself emotionally here on earth. His goal is to go to heaven. I know that,” Susan went on. “And he is going to go his own way.”

Buzz’s solitary silence irritates Susan. “It makes me really mad,” she said forcefully. “Sometimes, I would just like him to say something when he feels bad, you know.” She turned, as if facing her husband. “Why don’t you just say, ‘This is a bad day for me. I feel sick’? It is weird keeping something like that from me.”

This had been put to Buzz before. “Buzz gets angry when I tell him.” I pointed out to Susan that Buzz told me he never gets angry. She smiled. Sort of. “Well, he does not really show it. He just gets upset when we call him on it,” she said. “Ryan and I know when to back off.”

I asked her if she could understand how chronic illnesses can stretch couples to the point of splitting them apart. “Sure. The spouse gets tired of the stress day in and day out. If they are not open, a lot of people cannot take it.”

“And you?” I asked.

“I am not sure how we get by.”

It came back to their traditional faith. “We took wedding vows, you know, for better or worse.” The commitment between Susan and Buzz survives unquestioned. A life has been threatened, but the marriage is meant to live on. “Buzz and I take our promises to God seriously.”

Disease and divorce can travel together, and the toll is undeniable. All among us hear the horror stories.

My firefight with colon cancer seven years ago burned Meredith and singed the kids, but the fight had a beginning, middle, and end. Chronic illnesses such as Buzz’s have long if not endless middles. The conclusion of my struggle was happier than Buzz’s promises to be. We survived on our own brand of hope. Susan and Buzz have plenty of fuel on the fire to keep that flame alive.

TO HELP OTHERS die in peace has become a calling for Buzz. More than ten years ago, hospice workers had tended to his mother as she lay dying of breast cancer. He started working as a hospice volunteer in 2005, and a year later, hospice officials invited him to join the staff as the paid volunteer coordinator. He works three days a week. Hours are flexible, to suit his physical needs. “I work at my own pace. They are very protective. If you do not feel well, you do not have to worry.”

Paid work brought the sun back. “Oh, my.” Buzz sighed. “The job gave me self-worth. I was a man again.” That he found work became a banner headline in his mind. He become a professional cancer coper, and reclaimed his self-respect. He was back in the game.

Buzz was gleeful that at last he could take part of the financial load off Susan’s shoulders. “This is huge for Susan,” he said with pleasure. The position, though no guarantee of winning enough bread for every meal, was a shot in the arm for both of them. He began to feel more hopeful. Choosing his words carefully, he said, “For a cancer victim, hope is like winning the lottery.”

“Well, you know the odds on that one.”

“Yes,” he laughed, “but see, I can hope, too.” We sat at the dining room table, silent for a moment. I could hear Susan telling Ryan something up the stairs. “Hope is that the next day a cure can be found,” Buzz continued. “Maybe the next day, a gene will be recognized by some research scientist, who says, ‘Let’s attack this gene.’ That is going to stop lymphoma. That is going to be the big answer.”

For Buzz, hope said it all. “Hope is the ballgame of life,” he observed, “because if you lose your hope, if you lose that, then you just want to give up. Without hope, there is nothing.” Hope in a hospice has to be hard, but Buzz seemed to find much satisfaction in his work there. “My wife says I want to know what it is like,” Buzz said, “how people react at the end.”

He joined Susan in acknowledging that probably he did need to watch others die to prepare himself for his journey away from this life. “I cross the bridge with them. I have held their hands as they pass. If I have helped to make someone’s life better, I have done my job.”

“What do you get from this?” I asked.

“I feel a sense of peace.”

More power to him. The hospice did seem an appropriate place for Buzz to accomplish his personal mission: to remove fear from dying. It was almost as if he had been guided to the spot. He would tell me he was.

DURING MY FIRST visit to Franklin, Buzz and Susan and I piled into their van and embarked on a tour of the quiet streets. It was a weekday morning. There were no people anywhere. “My Lord, the churches are everywhere,” Buzz exclaimed. “Just look down the street,” he said approvingly. “There is Baptist, there’s Presbyterian, there is Pentecostal, there is Mormon, there’s Methodist.” And we had not turned a corner. “We are in the Bible Belt,” Susan added.

The sheer number of sanctuaries amazed me. “God is everywhere,” I said.

“Of course, my friend. Down here, there is not just one, but all kinds of Baptist, Southern Baptist, and Northern Baptist.”

“They are all separate churches?” I asked.

“They are all separate churches,” Buzz verified. “A lot of churches that are nondenominational are livelier than ours, more charismatic.”

“What does that mean?” I asked.

Buzz explained that these churches really rock. “They just let go,” he said, “with shouting and wild singing. There is hand raising and clapping.” He stopped for a moment. “I like variety,” he added. “We go to all these churches sometimes.”

“What do you get from that?” I wondered out loud.

“There is a kind of an awareness of other Christians, a renewal.” Buzz plays a set role in his own more conservative church. “At these other churches, I can worship the way I want, be myself,” he said. “There is good fellowship there. Our church is great but not at that point.”

At those sanctuaries where there is live music, perhaps Buzz does let go. “Stuff does build up and, wow. Oh, it offers a huge release,” he said with enthusiasm. “Susan does not care for the charismatic movement. That is okay. I sometimes go to one of these churches alone or sometimes with Ryan. There is a cleansing. It is like my therapy.”

“It seems as if one or another of God’s varied drumbeats keeps you going,” I observed to Buzz.

“It really is faith,” he responded.

I stared at him. “Faith in what?”

“God,” he said immediately.

“You believe God will help you?” I asked.

“I am certain,” Buzz answered without hesitation. “I will be cured in this life or in heaven.” I know. That assurance had become Buzz’s mantra.

Later that day, as the Bays and I bounced along in their van, a CD on the seat next to me caught my eye. I reached for it as we pulled up at a traffic light. The album was called Amazed, a Journey of Faith. There was a photo of three guys in front of a brick wall looking their Bruce Springsteen best, informal and intense. There, in the middle, stood Buzz. He had said nothing about the CD, just leaving it for me to discover.

“So you are the yodeling florist,” I said.

“You should hear his voice,” Susan said. “It is great.”

The recording is well done. “It is a journey of faith, my friend. / Step by step, He’s with you, / His loving knows no end,” went the title song. “He’ll chase away your darkest days and fill them with amazing grace. / Leave behind your yesterdays and today start a journey of faith.”

The CD was recorded in 2002, well after the cancer diagnosis. “The whole group knew the possibilities,” Buzz explained, “but we decided to keep singing our music ’til we can go no longer.” He said the CD was an independent project that paid for itself.

“Did the recording have anything to do with your illness?” I asked.

“Only that I wanted to have something to leave Susan and Ryan,” Buzz answered. “Something with my voice on it.” Each song in its own way became a statement of faith.

It struck me as odd to hear relatively young guys sing about God with such conviction. My cultural association with faith goes to old folks heading around the bend. Buzz wrote one more song for the most important member of a new generation, a fair-haired boy who pads around his own house.

“Oh, how he prayed to you, as he prayed for me. / He knew without a doubt, you would answer my needs. / So Lord I come to you. / I don’t know what I must go through, / but I will trust in you like I see Ryan do.” Buzz’s song for his son made clear that his faith has been passed down.

Christianity reaches deep into the Franklin community and is the defining piece of the culture for residents of all ages. This is the bosom of the Bible Belt. The citizens of Franklin are God-fearing, Jesus-loving Christians. For Buzz, Christianity is not part of life. It is life.

“You have to have faith to live around here,” said Kim, who with her husband, Craig, owns the Ashley-Drake, the local bed-and-breakfast where I stayed during each visit. Buzz had wanted me to stay there. The young couple displays no religious symbols on the walls of the quaint old place, no outward signs of their faith, but that faith was evident as we sat over coffee at an antique oak table. Christianity was their frame of reference, and it crept into many conversations.

The Franklin Memorial Christian Church is a large modern structure that looks as if it belongs in a shopping mall. The church serves as tabernacle and part-time theater. The sanctuary is immense, housing religious services and hosting Christian cultural events. The church is almost a complete world for its congregants. Buzz goes to one, sometimes two services on Sundays. Church events and activities fill out much of his remaining week.

Buzz’s devotion to his faith and church together is the linchpin of his life. A true sense of community is pivotal to him. No one wants to go it alone, and here he has found a spiritual sedative that gets him through the night. And though a nonbeliever such as I finds this focus on faith rather hard to accept, the church community is seductive. Communal caring can grow on anyone.

On one clear, cold night in December, I attended church with the Bays. It was shortly before the Christmas holidays, and Buzz had to jockey for a parking space. The pageant was the biggest show in town. I had set off to visit the Bays because Buzz wanted me to see Ryan play a Wise Man and hear him sing a solo in the Christmas spectacle.

The evening had the feel of a rock concert, the Stones go to church, with laughter and small talk and refreshments for everyone. These were people who were important to one another, individuals who touched each other’s lives.

These were Buzz’s people. I watched the man work the crowd, hardly a politician seeking votes, but an ordinary guy drawing sustenance from others. “You okay, Buzz?” punctuated the evening. A hearty handshake or silent squeeze supplanted the need for more words. Buzz smiled that smile and drew it all in. The scene played out in stark contrast to Denise’s chosen isolation. This church had become one man’s therapy. Buzz moved with ease, his complete faith and easy deflection mixing seamlessly, faith and denial coexisting comfortably.

Buzz’s minister, Rev. Larry McAdams, Larry to all, sees through the cheerful dance Buzz carefully choreographs for his audiences. “Buzz needs to talk about himself. He needs to tell someone how he feels. He reaches out to others in need. That is great, but…” But what? I wondered. Larry’s frustration with Buzz reads as tough love. “We ask Buzz how he is, and he comes out with trite little things like ‘They haven’t got me yet’ and ‘I’m upright and taking nourishment.’ I say, ‘Buzz, that is not good enough for me.’”

The reverend said Buzz avoids him sometimes, backing away from conversations he does not want to hold and, perhaps, emotions he does not want to face. “With illness or tragedy, anger is appropriate,” Reverend McAdams pointed out. Larry reminded me that Jesus said, “Be angry and sin not,” meaning, be angry, as angry as you want, but hurt no one with your rage.

Buzz, according to his minister, needs to face the music. “I do not think he levels with me or anyone else about what the doctors are saying. I do not know if Buzz has accepted the fact that nothing is going to save him.”

The reverend suggests that Buzz might be bargaining with the Lord. “Maybe Buzz really thinks God will prolong his life if he helps others.” He paused. “I have never seen anything like Buzz in thirty-six years of ministry,” Larry concluded. That was a powerful informed assessment.

Larry McAdams has been at this kind of work for a long time. Where the good reverend and I perhaps lose our footing is that I figure if Buzz is going to die soon enough, let the man do it his way. There is nothing that suggests to me that there is any benefit in facing the cold, hard truth, according to the terms of others. What is the virtue of staring yourself down in the mirror and emoting for its own sake? If we allow others to tell us how to live, they will want to tell us how to die. Their truths would not set Buzz free. Coping becomes whatever works, even if, for Buzz, that means joking too much and falling back on faith.

I respect those who find the faith that eludes me, but envy is not part of the package. The Almighty never cut me any slack, issued a rent check, or bought a sweater for me when I was shivering. When I was hungry, I fed myself. And here was Buzz, dropping every egg he could find into the bottomless basket of faith. His life was moving not so slowly in a bad direction. Yet the man believed that somehow the Lord would intercede and all would be made whole.

Even when his brother suddenly died, Buzz toed the line. “My brother is at peace,” he told me calmly. “He is with Mom and Dad and my sister up in heaven having a great old time.” He chuckled. I was long past the point when anything Buzz said surprised me.

This man’s faith is so complete, heaven so alluring, that death seems but a bend in the road. “Heaven is an incredible place where a lot of things and people, humanity, our family and friends are.” My friends ask all the time if I am envious of Buzz’s strong faith. I envy the peace faith gives to Buzz, but I cannot get there.

“Please tell me about heaven.”

“It is a place that is beyond anything I know, any pictures I could paint. There is no camera shot I could take that is more beautiful or more outstanding. There are no words that any poet could ever print.” I was mesmerized by the description. “For me, death is the gateway to a life of no pain, no worries. I will get to see people I miss, hug and live with them forever. How can that be so bad?”

“You really do believe that, don’t you?”

“I always have believed it. I have no fear of death.” There is a different fear. “I have a fear of leaving my family, but I know their faith will sustain them.” Buzz broke the spell with a laugh. “I think Susan will say, ‘Give me two weeks and I will be back out on the road, looking for somebody else.’” Buzz thought this was funny. “No,” Susan interrupted. “Yes,” Buzz answered. “First time, go for the love, and then go for the bucks.”

“Nice to see you laugh, Buzz. I just would be angry.”

“I know you want me to say that I am angry. I am not. This is just a brief stay on earth, and we all die. Through this trauma, I will shine for God and not look back. God knows our needs before we do. We cannot fool Him. I have not led a perfect life, but I have been forgiven.”

A STARBUCKS SITS conspicuously along Route 31 going into Franklin, standing alone among the gas stations and greasy eateries. My pumpkin latte and the eighteen-wheeler parked outside seemed a visual contradiction in terms.

“Buzz,” I asked, “has the certainty of your faith made you accepting of death and led you to stop fighting?”

“That is a tough one,” he said, pausing. “Since I know where I am going, I am not discouraged to die.”

“Really?”

“Yes. I know you will think I am crazy, but I am excited to go.”

“I already think you are crazy, Buzz,” I replied. “Then why fight it?”

“Because of Ryan and Susan,” he answered. “That is it.” Then he threw in one additional thought. “The only selfish motive is this. I do not want to be forgotten.”

Perhaps Buzz was not as immersed in denial as those around him are wont to believe. He did at times show flashes of anger, faint lightning in the distance. “I am angry at the disease for robbing me of so much stuff,” he finally conceded. “Obviously, yeah, I do get angry with things. I get, like, Why is this happening now? What purpose does it have? Why did I get this way?”

Our conversation was animated and loud. I looked around Starbucks and realized some folks were staring at us. Buzz told me that my presence in town had been duly noted.

“Buzz,” I kept on, dropping my voice, “I get mad for the same reasons you claim you should not. The angry response has little to do with logic or even faith. You can believe in God and still feel that you got screwed,” I continued. “You did get screwed. So did a lot of us. Maybe I am only attempting to justify my own life in a bubbling cauldron. Boiling over from time to time does present one big release. Get pissed off just once. Don’t laugh it off.”