Four

1932–1964

MUSEUM

By the time Osborn Oldroyd died in 1930, his collection of Lincoln memorabilia had outgrown the Petersen House. Director of Public Buildings Ulysses S. Grant III found money in his maintenance budget to move Oldroyd’s collection to the first floor of the old Ford’s Theatre building, which he dubbed the Lincoln Museum. The museum’s exhibits focused on Lincoln’s life, presidency, and death. The Petersen House was renovated several times over the next 30 years and was eventually restored in the late 1950s to its appearance on April 14, 1865.

At first, the Lincoln Museum drew little attention, but as the centennial of the Civil War approached and the museum received new artifacts, attendance grew. Still, visitors complained that it was hard to understand the events of the assassination when the building looked nothing like the theater in which Lincoln had been killed. In the 1940s, Sen. Milton Young of North Dakota began a decades-long legislative campaign to restore the building to its appearance on the night of the assassination. Following an intensive study of its history and structure led by National Park Service historian George Olszewski, Congress authorized a $2 million reconstruction based on Mathew Brady’s photographs as well as other evidence of the theater’s former appearance. Construction began in 1965 and was finished in 1967. The result was the replicated 1865-era Ford’s Theatre and facade of the Star Saloon as well as a new Lincoln Museum in the basement. The newly named historic site included the Petersen House across Tenth Street.

The National Park Service’s original intention was to use the site to present ranger talks and a sound-and-light show reciting the events of the assassination. Hearing of this plan, Frankie Childers Hewitt, a determined Oklahoman with connections in the political and cultural worlds, believed it both wasteful and disrespectful of Lincoln’s love of the performing arts not to produce live theater in the building. With great effort, she persuaded then Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall to authorize the resumption of live performances in the space. Hewitt created a nonprofit organization named the Ford’s Theatre Society to fulfill this mission upon the building’s reopening in early 1968.

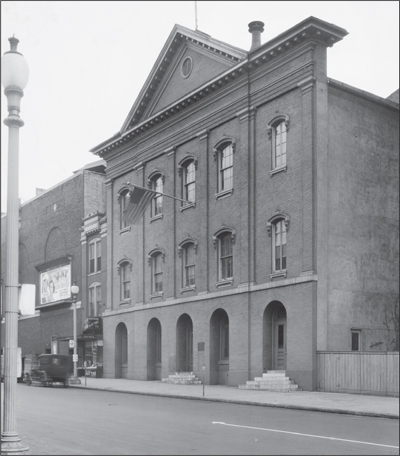

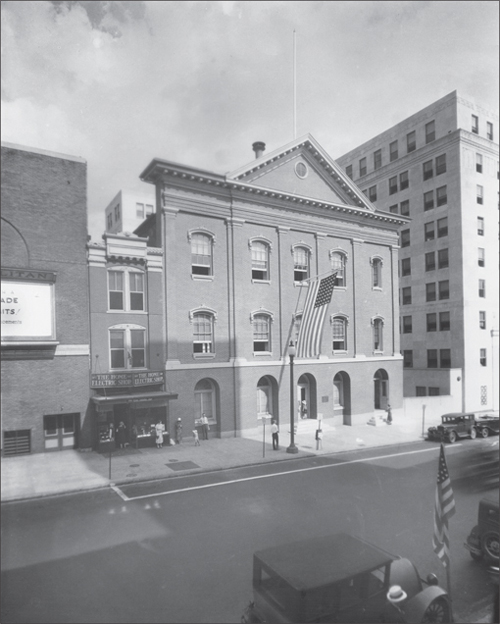

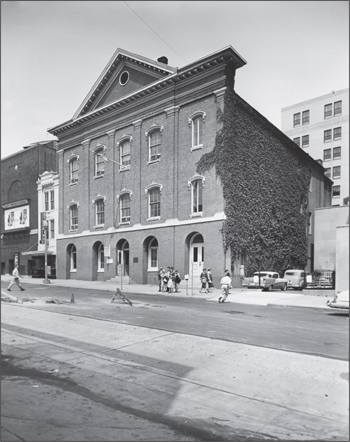

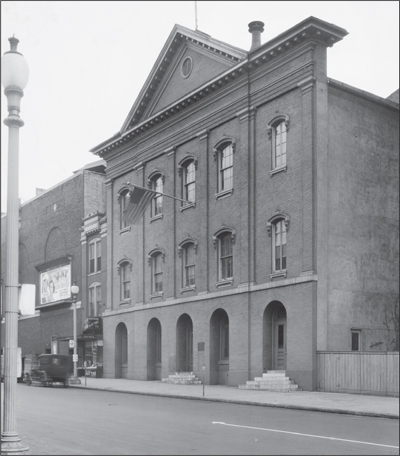

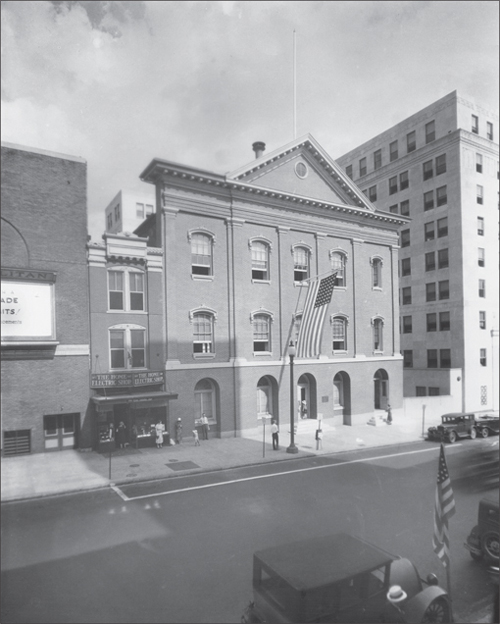

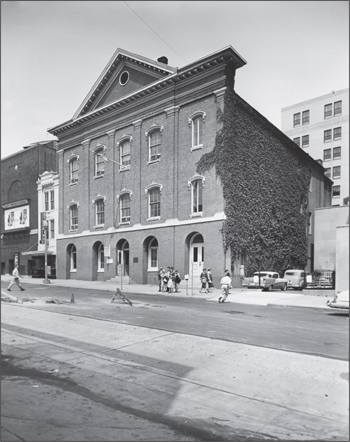

In the early 1930s, as shown at left, the building that once was Ford’s Theatre was a quiet, decrepit warehouse with an empty lot in the space where the old Star Saloon building had recently been torn down. In contrast, less than a block away, F Street, shown below in 1936, had become the city’s major shopping district. Washington’s civic leaders were by this time becoming more aggressive about using spaces around the city to recognize historical events. Seven decades since the Civil War, the emotional responses linking the Ford’s Theatre building with the assassination had faded. To some, the time seemed right to use this historic site to memorialize Lincoln. (Left, NPS; below, MLK.)

Osborn Oldroyd died in 1930, leaving the Petersen House without a caretaker for the Lincoln memorabilia collection that had now outgrown the building. Lt. Col. Ulysses Grant III, the director of Public Buildings, had supported Congressman Rathbone’s campaign to transform the Ford’s Theatre building (shown here in 1931) into a museum and veterans’ group headquarters. Grant particularly wanted to move the Oldroyd collection across the street to provide better public access and protection from fire. Both Grant and Rathbone expressed reservations about restoring the building to its former use as a theater. Moving the Oldroyd collection also would allow Grant to renovate the Petersen House to make it look more like it did the night Lincoln died. After Congress repeatedly declined to appropriate funds for these purposes, Grant reallocated some maintenance funds from his own budget to perform a modest refurbishment and installation. (NPS.)

The new Lincoln Museum opened in the first floor of the former Ford’s Theatre on February 12, 1932 (Lincoln’s 123rd birthday). By contrast with the Lincoln Memorial, which focused on President Lincoln’s stature as savior of the Union, the Lincoln Museum displayed memorabilia focused more on his human characteristics. (NPS.)

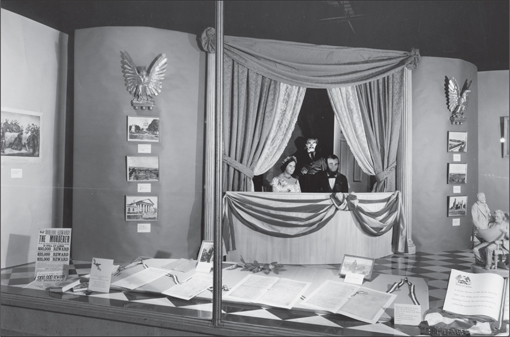

The museum’s glass-topped cases, wall-mounted boards, and niches contained thousands of Lincoln-related objects from the Oldroyd collection and other sources. One newly displayed item was a painting made from a sketch created on April 14, 1865, of the dying president being carried across the street to the Petersen House. (NPS.)

Although transferred to the National Park Service in 1933, the Lincoln Museum suffered from a lack of visitors in its initial years, possibly because of its limitations as a museum. It was in a drab office setting rather than in the theater that occupied the public’s imagination, and it initially lacked interesting artifacts about Lincoln. And, as curator John T. Clemens reported, the 10¢ admission charge limited attendance during the Great Depression. (NPS.)

The Lincoln Museum acquired additional artifacts over the years. During the 1930s, members of the Civilian Conservation Corps constructed relief maps and models for the museum to illustrate different events of Lincoln’s presidency. Later, the museum received and protected a Civil War–era cannon that was at risk of being melted down for scrap metal during World War II. (NPS.)

In 1940, the museum obtained from the judge advocate general’s office of the War Department the Deringer pistol that John Wilkes Booth used to kill Lincoln (shown above). The museum also acquired cartes de visite (visiting cards) that were given to Booth by some of his female admirers and were found in his pockets upon capture, along with Booth’s boots, the bar he used to prevent access to President Lincoln’s box, and other miscellaneous artifacts from the assassination. In the image below, Edwin B. Pitts, the chief clerk of the judge advocate general, is shown playing with Booth’s gun. Modern-day museum practices forbid such antics and require instead minimal, careful handling using gloves. (Above, NPS; below, LOC.)

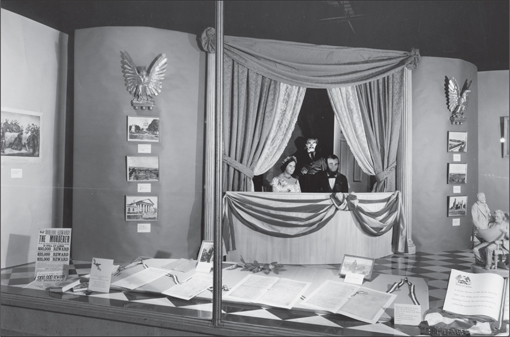

Notwithstanding previously stated concerns that a full restoration of the building as a theater would inappropriately glorify John Wilkes Booth, many visitors expressed disappointment that the museum’s layout in a government office building prevented them from understanding where and how the events of April 14, 1865, occurred. Museum management tried to help them by displaying photographs of the theater’s interior and drawing black lines on the floor to mark both where the stage and the Presidential Box once stood and the path by which Booth made his escape. The museum also featured dioramas of the theater’s interior and of Booth shooting Lincoln, as shown in both images here. (Both, NPS.)

In 1959, John T. Ford’s great-grandson Addison Reese (far left) donated several original artifacts from Lincoln’s box that had long been in his family: the lithograph portrait of George Washington and the sofa upon which Major Rathbone had sat the night of the assassination. Note the arrows showing the nick on the portrait of Washington and the tear said to have been made in the Treasury flag (given to the museum in 1932) by Booth’s spur when he jumped to the stage. The image below shows a park historian pointing to a mark on the frame of the Washington portrait that Booth may have made. The sofa and portrait today occupy the re-created Presidential Box; the original Treasury flag is in the theater’s basement museum. (Both, NPS.)

By the 1950s, an information center was installed at Ford’s Theatre, and the museum had almost 150,000 visitors per year. The upper floors served as offices for National Park Service staff who answered tourists’ questions about Lincoln and his assassination. In the early 1960s, the Lincoln Museum was hosting lectures by noted scholars about Lincoln’s life and his presidency. The image below from 1962 shows an address by Civil War scholar Elden E. Billings on “The First Two Years of the Lincoln Administration.” (Both, NPS.)

After Oldroyd’s Lincoln collection moved out of the Petersen House in 1932, five women’s patriotic organizations conducted a partial renovation based on a diagram of the house as it had been shortly after Lincoln’s death. Their objective was to make the house look more like the Petersen House of 1865—an example of a middle-class home of the Civil War era. The Interior Department made more repairs to the Petersen House in 1944 and 1945 and later performed a more historically accurate restoration in 1958 and 1959. The above image shows the front parlor after the 1959 restoration. The sofa in the image below came from the Lincoln family home in Springfield and was brought by Oldroyd when he relocated to Washington in the 1890s. (Above, LOC; below, NPS.)

After the 1959 restoration, the room in which Lincoln died contained furnishings similar to those in the room in 1865. A copy of the Village Blacksmith replaced the one that had previously hung on the wall, and above the bed was a copy of Rosa Bonheur’s The Horse Fair. The wallpaper was a reproduction of the original pattern, and the bed and chairs closely resembled those in the room at the time of Lincoln’s death. In the picture below, Dorothy Kunhardt, a Lincolniana collector, holds an image of Lincoln’s death room that was taken by Petersen House boarder Julius Ulke on the morning of April 15, 1865. (Right, LOC; below, NPS.)

In December 1945, Washington attorney Melvin Hildreth wrote to Sen. Milton Young of North Dakota (pictured above) suggesting that money be appropriated to restore Ford’s Theatre to its 1865 appearance. Young, who had visited the Lincoln Museum and been disappointed that its interior bore no resemblance to the historic space, agreed and introduced a resolution directing the secretary of the Interior to estimate the cost of reconstructing the theater. A supporter of Senator Young’s bill wrote in a Washington Post editorial, “The low-ceilinged room to which the public is admitted . . . is thickly studded with supporting pillars and glass showcases which afford meager material for reconstructing the scene on [April 14, 1865]. Except to the liveliest imagination, the structure is far less suggestive of the playhouse than of Government offices, warehousing and other utilitarian uses to which it has been put. Senator Young’s proposal deserves universal and unflagging support.” Young’s resolution failed, as did another resolution introduced in 1951. Finally, after eight years of lobbying, a third bill was approved and signed by Pres. Dwight Eisenhower in 1954. (NPS.)

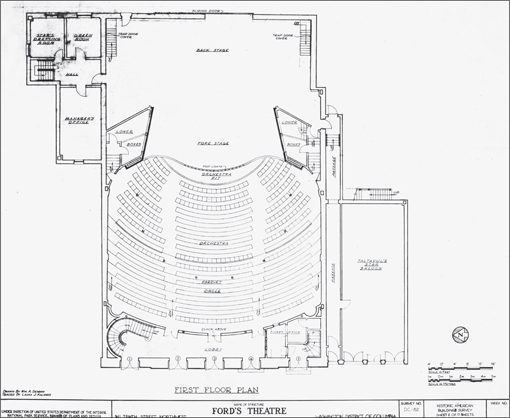

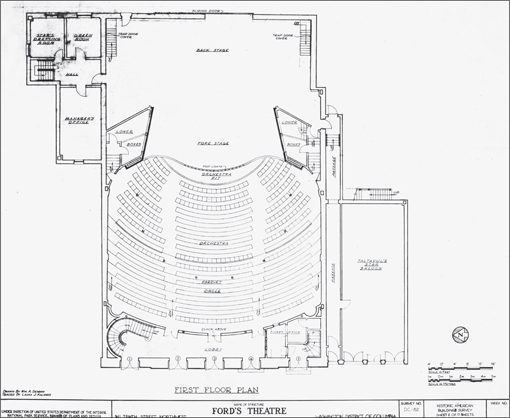

In 1960, Congress appropriated $200,000 for the National Park Service to complete preliminary architectural and historical research on the Ford’s Theatre building. The project was assigned to George Olszewski, a National Park Service historian and World War II veteran who had attended a performance at John T. Ford’s Baltimore theater as a child. Olszewski, working out of his National Park Service office in the former Ford’s Theatre building, undertook comprehensive and meticulous research to determine the structure’s 1865 appearance from, among other things, Mathew Brady’s post-assassination photographs. In 1962, he published the 138-page Historic Structures Report that described the building’s history and included blueprints for its renovation. The publication would serve as a road map for the future restoration of the site. (Both, NPS.)

The proposed restoration of Ford’s Theatre came at a time when downtown Washington, DC, was deteriorating. Although the center of action from the 1830s through the 1930s, downtown Washington began a gradual decline in the 1940s as people moved from the central city to the far regions of the District of Columbia and the Maryland and Virginia suburbs. Businesses followed them, relocating to malls and abandoning downtown to small-time retailers and empty storefronts. Driving down a decrepit Pennsylvania Avenue during his 1961 inaugural parade, Pres. John F. Kennedy was appalled by the shoddy condition of “America’s Main Street” and appointed then assistant secretary of labor (and later US senator) Daniel Patrick Moynihan to develop a plan to rejuvenate the downtown. (Both, MLK.)

To build public support for the restoration of the theater, Olszewski mounted an international press campaign in newspapers and magazines as well as on the radio. It worked. Citizens wrote their congressmen asking them to appropriate money to rebuild the theater and sent in donations themselves. President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 created renewed interest in Lincoln’s shooting and support for restoring the place where it occurred. On July 7, 1964, Congress appropriated $2 million to restore the site. The lead architect was Charles Lessig, shown here. Lessig had previously worked on the restoration of several other Civil War–related historic sites, including the Custis-Lee Mansion overlooking Arlington National Cemetery, the McLean House in Appomattox (where General Lee surrendered), and several sites in Gettysburg. (NPS.)

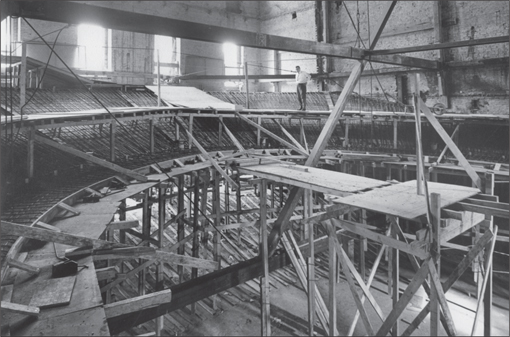

The Ford’s Theatre building housing the Lincoln Museum was closed to the public on November 29, 1964, and renovation began in January 1965. The interior of the building was completely gutted, the basement excavated, and the exterior walls reinforced. Olszewski remained a constant presence throughout the project, ensuring the historical accuracy of the construction and photographing all its stages. (NPS.)

The restoration was meant to duplicate the 1865-era theater in appearance while meeting modern safety and engineering standards. This image shows the scaffolding in front of the building, where workers reduced the windows’ size (which had been expanded to provide more light for late-19thcentury government workers) to that of 1865. The fill-in brickwork around the front windows from this project is still visible today. (NPS.)

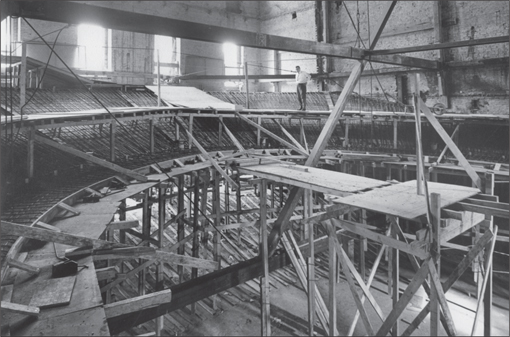

Builders used Olszewski’s report, which included newly drawn blueprints of the 1865-era structure and drawings of building details—such as window and door framing, columns, and molding—to construct a replica of the theater, albeit with modern facilities expected of a 20th-century performing-arts establishment. The image above, looking toward the front of the theater, shows the structure for the Dress and Family Circles. The image below, taken later, shows the stage in the foreground, two of the stage-left boxes (including the Presidential Box), and part of the Orchestra and Dress Circle seating areas. (Both, NPS.)

As part of the effort to ensure historic accuracy, the restorers replicated 1860s-era backstage rigging featuring a complex system of ropes and pulleys to manually raise and lower backdrops. This proved cumbersome to 20th-century stagehands, so a state-of-theart, automated rigging system was installed later to meet current technological needs and safety standards. (NPS.)

Workers restored the stage and boxes (including the Presidential Box) to their 1865 appearance. For the anticipated 1968 reopening of the theater, designers reproduced the set of Our American Cousin, the play that was being performed the night Lincoln was shot. While this backdrop proved useful for National Park Service programming about the circumstances of Lincoln’s assassination, that play has not been performed at the renovated Ford’s Theatre. (NPS.)

The National Park Service renovation project included a partial reconstruction of the Star Saloon. Although its front exterior was built to reflect its appearance in 1865, the interior contained, instead of a bar, a box office for the theater on the first floor and offices and conference rooms for National Park Service staff on the upper two floors. (NPS.)

The renovation was finished in late 1967. This image shows the completed front of the theater and Star Saloon, including such historically accurate details as the sign pointing to the Family Circle entrance and providing the historical price of 25¢. (The Family Circle is no longer used for patron seating but instead houses the stage management booth and theatrical lighting equipment.) (NPS.)

The above image was taken from stage right and shows the Orchestra and Dress Circle levels. The freestanding wooden chairs, evocative of the 1860s, proved to be too uncomfortable for 20th-century patrons. The boxes—consistent with original design—faced away from the stage and toward the audience, making them undesirable for theatrical viewing; hence, they were not made available for patron seating. While the flags draping the box are reproductions, the framed engraving of George Washington mounted to the balcony during the renovation is original. The image below, taken from the Orchestra level, shows the orchestra pit in front of the stage as well as the doors leading to the two stage-left boxes. (Both, LOC.)

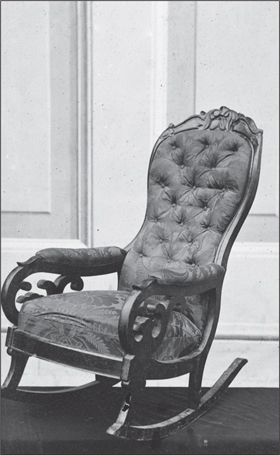

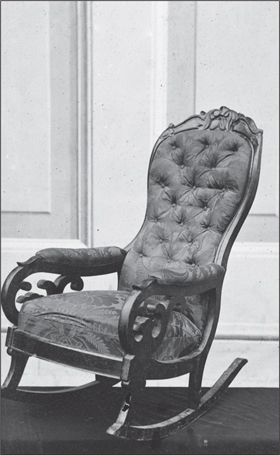

The image at right shows the interior of the Presidential Box, renovated to its appearance on April 14, 1865. While the sofa is original, all other furnishings in the box are historically accurate duplicates. The actual chair in which Lincoln sat (shown below) was sold by Ford family members and eventually acquired by the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, where it is on display today. The stain near the top of the chair is not Lincoln’s blood (he bled very little while still seated). Instead, it is hair oil from the many people who were allowed to sit in it after Lincoln died. The worn-out fabric is, likewise, the result of post-assassination usage. Such handling of a valuable historical artifact is a relic of an earlier, more permissive approach to historic preservation. (Right, photograph by Carol M. Highsmith, NPS; below, LOC.)

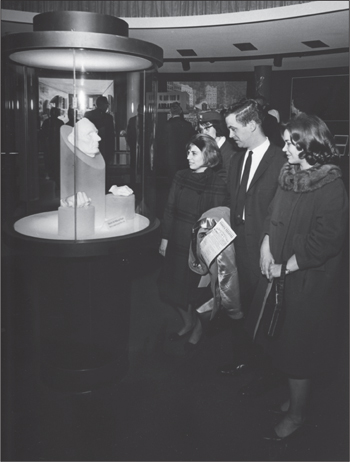

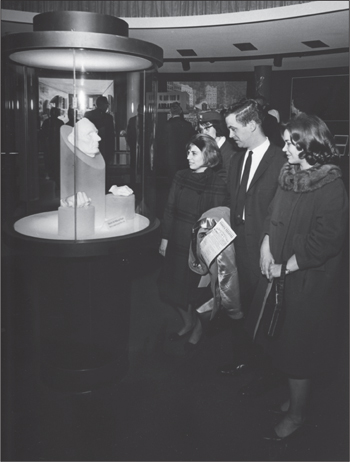

The artifacts of the former first-floor Lincoln Museum were moved to a new museum in the basement of the renovated theater. The museum had a circular setup; artifacts and images from Lincoln’s life and assassination were displayed along with wax figures on the outside walls, leading to the center display of Lincoln’s life mask. Responding to long-standing concerns that the renovation would glorify the murder in a decade marked to that point by the 1963 Kennedy assassination, the 1968 museum focused on Lincoln’s life and de-emphasized the events of his killing, barely mentioning the fate of Booth and his conspirators or public reaction to Lincoln’s death. (Both, NPS.)

The Lincoln Museum contained artifacts from the Oldroyd collection plus many new items obtained over the years. A centerpiece of the museum was a life-mask cast of Lincoln’s face in 1860. The museum also obtained the overcoat Lincoln wore the night of his assassination, which Mary Todd Lincoln had given to the White House doorkeeper after her husband’s death. In 1967, one of the doorkeeper’s descendants sold the coat to a private organization that donated it to the National Park Service museum. Lincoln’s coat today is in fragile condition and so is kept in long-term storage for its protection. (Right, NPS; below, FTS.)

The final piece of the Ford’s Theatre restoration was the reconstruction of the open-flame gas lantern that stood outside the building in the 1860s. On September 24, 1971, Senator Young, who had lobbied so long to restore the theater, was given the honor of lighting the lantern. (NPS.)

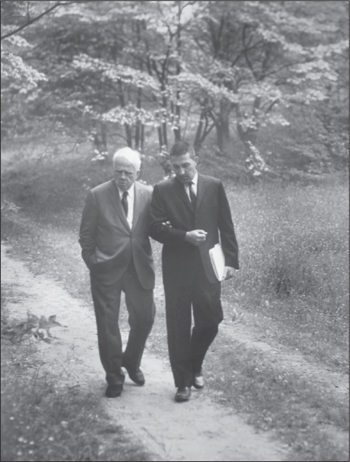

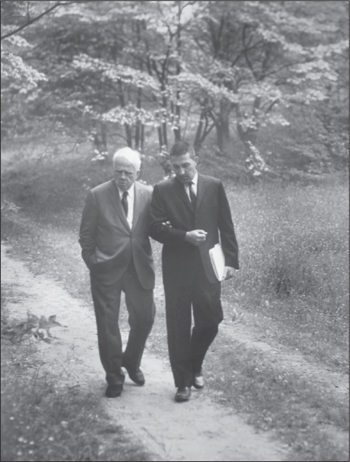

Stewart Udall, shown walking to the left of poet Robert Frost, was a key figure in the restoration of Ford’s Theatre. Udall was a congressman until President Kennedy appointed him secretary of the Interior, overseeing the National Park Service. Secretary Udall held this post until the end of the Johnson administration and achieved the enactment of environmental preservation laws and the creation and renovation of national parks and historic sites, including Ford’s Theatre. (Udall estate.)

A meeting between Secretary Udall and Frankie Childers Hewitt (shown here in the 1970s) would have a profound effect on Ford’s Theatre. Hewitt, the daughter of refugees from the Oklahoma Dust Bowl, grew up in California. After moving to Washington, DC, in the 1950s, she became staff director of a Senate committee and then a public affairs advisor to United Nations ambassador Adlai Stevenson during the Kennedy administration. Married to 60 Minutes producer Don Hewitt, Frankie Hewitt, by the mid-1960s, had strong connections in both the political and media worlds. In 1965, Secretary Udall told Hewitt that Ford’s Theatre was being restored. When Hewitt asked if live theater would be presented in the building, Udall said, “No, the government can’t run a theater.” Hewitt opined that not presenting live theater at Ford’s Theatre would constitute “building a monument to John Wilkes Booth.” Hewitt later introduced Udall to the director of the National Repertory Theatre, who convinced Udall to permit live theatrical productions on the Ford’s Theatre stage. (Cassara.)

Realizing she needed to start a nonprofit entity to present theatrical productions at Ford’s, Hewitt enlisted President Kennedy’s former speechwriter Ted Sorensen, an attorney, to draw up the legal papers creating the Ford’s Theatre Society and negotiate an agreement with the National Park Service to produce shows at the venue. Frankie Hewitt’s husband suggested raising money for the new theatrical productions by soliciting corporate sponsorship of a televised broadcast of the opening-night performance. The Lincoln National Life Insurance Company expressed tentative willingness to provide the financing, but its chief executive sought White House support before committing. Using her political connections, Hewitt introduced the company official to the first lady, Lady Bird Johnson (shown here with Hewitt), whose endorsement secured the necessary financing. (Cassara.)