Pneumatic Railways

At the start of the Victorian era, steam power was behind the rapid development of the railway system. By the end of the era, Britain’s first electric railway had been opened in Brighton, pointing the way to the eventual electrification of Britain’s rail system, both overground and underground. But between steam and electricity there emerged, for a brief time, another motive force that some saw as the ideal way to power a railway: compressed air. It led to the rise and inevitable fall of the pneumatic railway.

Consider a railway carriage, large enough to accommodate a suitable number of seated passengers. Insert this carriage into an air-tight, tubelike tunnel and use a huge fan to generate enough air to blow it from one end of the tunnel to the other. Then reverse the fan’s rotation to produce a vacuum that has the effect of sucking the carriage back again. That, basically, was the theory behind the pneumatic railway.

The idea did not begin as a means of transporting passengers. It was seen initially as a method of moving cargo, and in particular, for transporting Post Office mail. The man behind the idea was civil engineer Thomas Rammell. He proposed his ideas in 1839, which led to a small-scale trial of his system on land near Birmingham, using a type of fan originally designed for coal mine ventilation. The trials were successful and a full-scale experiment was planned using a cast-iron tube made by the Staveley Ironworks in Derbyshire.

The first experiment

The tube was not circular, but took the shape of a traditional railway tunnel, with a height of 2 feet 9 inches and a width that varied between 2 feet 4 inches and 2 feet 6 inches. It was made in 9-foot lengths, each weighing around 1 ton. Raised ledges, 2 inches wide and 1 inch high in the base of the tube, were used as rails, on which small, elongated capsulelike carriages ran.

The experimental pneumatic railway test at Battersea.

The location for the experiment, which took place in May 1861, was Battersea, in London. The assembled length of tube began at the steamboat pier and ran for 452 yards along the banks of the river Thames, incorporating along the way several twists, turns and gradients. At the far end of the tube, a steam engine drove a 21-foot flywheel that also acted as a fan. When set in motion, it created a vacuum, resulting in the capsule at the Battersea end leaping into life and travelling along the length of the tube in about thirty seconds.

The first experiments were with the capsule loaded with bags of gravel, but the temptation for a person to travel down its length was obviously too great, and soon workmen from the building of the system were squashing themselves into the small capsules to see what the journey was like for passengers. Luckily, it transpired that during the journey, there was enough air in the tube to keep these early passengers alive and relatively well.

Public exhibitions followed and it soon became the vogue for more people to risk journeys down the tube. The Illustrated London News in August 1861 stated:

One trip was made in sixty seconds, and a second in fifty-five seconds. Two gentlemen occupied the carriages during the first trip. They lay on their backs on mattresses with horsecloths for covering, and appeared to be perfectly satisfied with their journey.

Brave passengers prepare for a ride in the freight-carrying carriages that travelled along the tubes of the Pneumatic Despatch Company.

Following the success of the trials, the London Pneumatic Despatch Company was formed and work began on laying pneumatic railway tubes underground, for use by the Post Office. The first line began at Euston Station and operations to carry mailbags began in February 1863. That same month, The Times newspaper reported:

Between the pneumatic despatch and the subterranean railways, the days ought to be fast approaching when the ponderous goods vans which now fly between station and station shall disappear for ever from the streets of London.

The system carried on transporting mail under the streets of London until 1874, when the Post Office cancelled the contract because the use of the railway was no longer economically viable. The London Pneumatic Despatch Company subsequently closed in 1875.

The Crystal Palace pneumatic railway

Meanwhile, Thomas Rammell had turned his thoughts to a more ambitious project: a full-size pneumatic railway designed to carry passengers in spacious comfort, as opposed to the risky, flat-on-their-backs, claustrophobic journeys hitherto taken by adventurous pneumatic railways passengers.

His chosen site for the first passenger pneumatic railway was the rebuilt Crystal Palace in South London, where it fitted in well with the many other weird and wonderful attractions of the park.

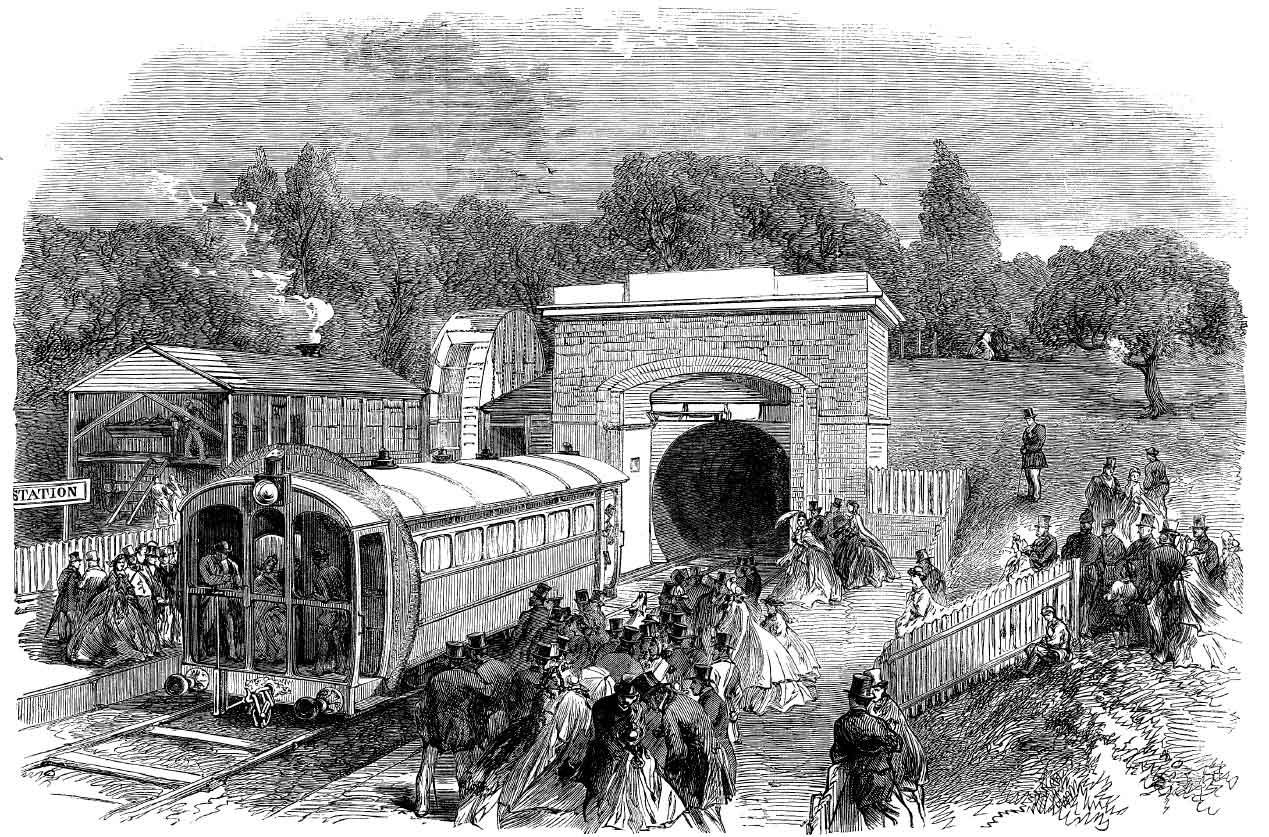

Entrance to the pneumatic railway that ran for a few brief months at the Crystal Palace in South London.

The railway was built in a 600-yard brick tunnel, 10 feet high and 9 feet wide. The carriage was capable of carrying up to thirty-five passengers, who entered through sliding doors at each end. A fringe of bristles surrounded the carriage and brushed the walls of the tunnel to make the necessary air-tight seal. The air needed to move the carriage came from a steam-driven 22-foot fan at one end.

The carriage began its journey as iron doors closed behind it and air from the fan was blown up through a floor vent to propel the carriage along railway tracks to the opposite end. For return trips, the fan was reversed to set up a vacuum that caused the carriage to move back in the opposite direction, by extracting air through a grill in the tunnel roof.

The Crystal Palace pneumatic railway opened for business in 1864 and was operated for only two months, during which time, passengers were charged 6d (2½p) for each trip.

The Waterloo to Whitehall pneumatic railway

The relatively short life of the Crystal Palace railway was, however, little more than a prelude to a much more ambitious project to build a pneumatic railway from Waterloo, under the river Thames to Whitehall. Carriages were expected to run one every three or four minutes, with fares of 2d (a little under 1p) for first class travellers and half that for second class. By running about fifteen trains an hour, from 7.00 am to midnight, it was calculated that the railway should make something like £23,268 per year, enough to give investors a good return on their money.

The 22-foot diameter fan used to propel the carriage was to be situated at the Waterloo side, and used to both blow the carriage to Whitehall and then to suck it back again. Two sets of iron doors would prevent the air being blown into the stations at each end.

Construction began in October 1865. The tunnel was to be made from an iron tube encased in concrete. On each side, cut and cover tunnels were built for the two termini on the banks of the river, from where the tunnel tube ran into the water, supported on brick piers anchored into the river bed.

Construction continued for twelve months. But then came the great financial panic of 1866, following the collapse of wholesale discount bank Overend, Gurney and Company in London, coupled with the abandonment of the silver standard in Italy. As a result, a banking crisis hit London and funding for the railway dried up. Despite appeals for funds and pleas to the government over the next few years, the project was eventually abandoned in 1869.

That really was the end of any real practical attempt to build a pneumatic railway in Britain, although there were those who continued to put forward ideas that failed to come to fruition.

The South Kensington pneumatic railway

In 1877, a company was formed to construct a pneumatic railway between South Kensington Station, which was served by the Underground District Line, and the Albert Hall, about a quarter of a mile away. The man behind it was, once again, Thomas Rammell.

Describing the proposed railway, The Illustrated London News in June 1877, stated:

No doubt our readers will be familiar with the pneumatic system in which passengers are blown through a tube by a gentle gale of two or three ounces of pressure to the square inch in well-lighted, comfortable carriages free from smoke, dust, heat and smell.

It went on to describe the various failures of the system in the past, but added:

As far as we can ascertain after careful inquiry and investigation of the system, the failures have had nothing whatever to do with the mechanical principles involved. There is no doubt that Mr Rammell can blow a train loaded with passengers through a tube, say, a mile long, with ease, certainty and economy, while the passengers will travel with a comfort as regards ventilation, quite unknown on the steam worked underground railway.

The plan for Rammell’s latest pneumatic railway was to solve the problem of passengers who alighted from the Underground at South Kensington Station having to make their way to nearby attractions of the South Kensington Museum, Albert Hall or Horticultural Gardens. The public were happy to pay a small sum to travel the short distance by omnibus, and so a pneumatic railway to cover the same route seemed like it would be a viable proposition.

The proposed route of the South Kensington Pneumatic Railway that was never built.

The tunnel was to be made of brick with a paved floor, rising from the underground station to the Albert Hall with a gradient of 1 in 48. The train would be blown along it, not by a fan as had been the case in previous pneumatic railways, but by a huge centrifugal pump driven by two steam engines.

The train would consist of six carriages, travelling on rails with a 4-foot gauge, and capable of carrying 200 passengers. When the train was not running, it was planned that the tunnel would be open to the public to walk its length.

The idea won much support. Rammell got together a board of directors for his company, the Metropolitan and District railway companies supported the plans and a 4½ per cent dividend was guaranteed for investors in the scheme, which required £60,000 capital.

The press were equally enthusiastic. ‘No novelty is involved in the scheme and of its mechanical success we have no doubt,’ said The Illustrated London News.

Despite the drawing of elaborate plans for the railway, and enthusiasm by the press and the engineering fraternity alike, the South Kensington Railway was never built. Thomas Rammell died two years later in 1879, after developing diabetes.

Other pneumatic railways

Another pneumatic railway was planned to travel under the river Mersey, connecting Liverpool and Birkenhead. The tunnel was built, but then plans were changed for it to be used by steam locomotives.

Tentative unfulfilled plans were even put forward for a pneumatic railway under the English Chanel in 1869. It didn’t happen.

The idea was not unique to Britain. Also in 1869, American inventor, publisher and patent lawyer Alfred Beach began building a pneumatic railway under Broadway in New York City. His Beach Pneumatic Transit Company succeeded in building a tunnel 312 feet long in just fifty-eight days. Beach initially put the scheme forward as a system for transporting mail, but by the time it was completed he had opened it to passengers with the idea of extending the line to Central Park.

At the time of its opening, however, there was no real final destination for the railway, and so passengers could only ride through the tunnel to the end of the line and back again, for no reason other than the actual experience. Nevertheless, interest was high at the start, but delays in getting permission to extend the line to anywhere worth visiting, coinciding with a stock market crash that halted any potential investment, meant that public interest eventually waned and the railway was closed in 1873.

Pneumatic railways, on both sides of the Atlantic, had reached the end of the line.

Tunnel entrance to the Beach Pneumatic Railway in America.