Government Owned Pensions: Asset Allocation and Governance Issues1

How government owned pension funds are exercising greater influence on the markets.

This chapter, surveys the role of government led pensions in international capital markets. Changes in the asset allocations of these funds have boosted demand for equities and alternative assets, a trend which is likely to continue despite losses sustained in 2008. Moreover, as with other government investors, the political oversight does present some key governance issues. Pension funds of Asian and Middle Eastern countries present the greatest potential for diversification given the relatively conservative asset allocation and the fact that some of these economies are just developing their retirement savings systems.

With aging populations and worsening dependency ratios in advanced economies, and a need to extend coverage in developing countries, in recent ye ars. public pension funds sought to make up their funding gap by moving; into higher risk assets and injecting more funds. In practice the asset allocations of public pension funds have become roughly similar to their private sector counterparts and to other institutional investors like endowments and foundations. All have allocated more towards equities and alternative assets which has led to near term losses

For emerging market economies which tend to have less developed pension systems but face aging populations, this challenge has arisen quickly. As such pension funds play a key role in the overall asset allocation strategies of their sponsor governments and have been called on when capital has been required by other parts of the government. And given the need to spend more on retirement these funds will have a greater impact on international markets

Despite similar asset allocations to other investors, the public ownership poses a special set of issues — even arms-length funds might make investment decisions for not solely economic reasons. Savings earmarked for retirement either of all citizens or public sector workers are but one pool of capital for some governments. As such they may be subject to political pressures, raided to meet other shorter-term liabilities. Utilizing such funds has allowed some governments to avoid taking on substantial short-term debt to finance anti-crisis measures. However the timetable for recapitalizing the funds is uncertain. Moreover fear of losing public funds could lead to less than ideal investment decisions or lead to pressures to support other key policy goals. While these investments may be in the national interest, it is possible that they might lead to suboptimal policies and lower investment returns.

Table 10.1 shows the assets of selected public pension funds.

Table 10.1: Assets of Selected Public Pension Funds Reserve Funds, $ billion. Adapted from Sovereign Wealth Funds and Pension Funds Issues. (OECD)

|

Country |

Size of Fund |

|

US Social Security Trust Fund |

2,200.0 |

|

Japan |

1,217.6 |

|

South Korea |

228.7 |

|

China |

138.0 |

|

Sweden |

136.7 |

|

Canada |

111.3 |

|

Australia |

49.1 |

|

France |

47.0 |

|

Spain |

44.9 |

|

Russia |

32.4 |

|

Ireland |

29.0 |

|

Norway |

20.4 |

|

Thailand |

11.6 |

|

New Zealand |

9.5 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

8.6 |

|

Portugal |

8.3 |

|

Mexico |

7.4 |

|

Jordan |

5.3 |

|

Pakistan |

2.4 |

|

Poland |

1.8 |

Types of sovereign funds

Sovereign pension funds can be divided up into several groups both based on fund structure and the entity to which they report. For the purposes of this analysis, there are three major types of public pension fund. These categories are informed by the work the OECD and others have done on this issue (OECD 2008).

National pension funds based on individual contributions These tend to be financed by payroll tax deductions or other individual contributions. Some countries allow the beneficiaries to choose the asset allocation from several choices, others invest the pool. Many of these funds have fairly conservative asset allocations with fixed income dominant. Given the changing demographic structure, a pay as you go type system will be unsustainable as the number of workers falls and the number of pensioners will rise as lifespans lengthen. As such greater asset diversification is likely.

National (or sub-federal) Pension reserve funds The financing gap triggered the creation of reserve funds which will eventually be connected to the pension system Many countries have established reserve funds with investment portfolios in an effort to plug funding short-falls. These funds, which tend to be under the supervision of government finance ministries even if the management of capital is outsourced to asset managers, are intended to feed into the public pension system at a later point when pay-as-you-go becomes too costly or when the reserve fund has amassed enough money. Examples include the Irish Pension Fund general reserve, the Australian future fund and the Chinese national pension reserve fund.

While the ultimate beneficiary are citizens, the current manager and beneficiary is the government and the political pressure to use the funds to meet other government priorities may be quite high. Government spending tends to require parliamentary approval. As such, pension reserve funds tend to be functionally similar to some so-called sovereign wealth funds which are government owned investment vehicles that manage funds in a variety of asset classes to maximize the long-term value of national wealth.

Pension funds for public sector workers These pension funds, particularly in the U.S. and Canada and often at a subfederal level are based on employer and employee contributions and tend to be defined benefit. These tend to be managed by a board appointed by political leaders. Some of these funds including Calpers and the Ontario teachers were among some of the earliest such investors to expand their asset allocations in alternative assets. Many may be a hybrid of the first two structures with a section pay as you go and investment portfolios separated out for longer horizon investment

In addition to official pension reserve funds, many countries have other assets that are either explicitly or implicitly linked to retirement funding. The sovereign wealth funds of Norway and some other commodity exporting nations have been earmarked to meet pension liabilities at an undefined point in the future. However pension funds unlike sovereign funds tend to have defined liabilities. Sovereign funds are also designed to cushion domestic economies from volatile revenue streams as well as preserve the value of national wealth. The link between the future liabilities and current asset management strategy is not necessarily clear and some governments might choose to spend the funds rather than saving them for the long term. As such the assets of a pension fund or pension reserve fund might be best assessed next to the overall liabilities of the government in question not just the retirement funding needs.

Is there a common asset allocation for pension funds?

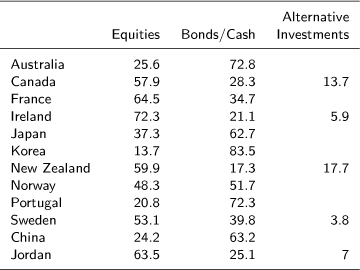

While the asset allocations vary across country and fund type, many public pension funds are coalescing towards a common allocation with a majority in equities, some investment in private equity markets, and many investing in hedge funds or funds of hedge funds. Despite an increased investment in equities especially by pensions in Europe, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, several funds including the U.S. are completely invested in bonds. See Table 10.2 for the asset allocation of several selected funds. This asset allocation not so coincidentally is similar to a common allocation that endowments, foundations, sovereign wealth funds and others have followed. This asset allocation suffered severe short-term losses in 2008 given the correlated losses of most asset classes, especially public and private equity, corporate bonds and especially any leveraged assets .

Table 10.2:Asset Allocation of Selected Public Pension Funds. Adapted from OECD, 2008

Many pension funds, especially from small open economies have increased their exposure to foreign assets especially equities. Funds from Canada, New Zealand and France all have close to 40% exposure to foreign assets.

It may take quite some years for pension funds to recover from the losses in 2008. World Bank research suggests that returns of pension funds, mostly in the developing world suffered losses of 8-48% in the year ending in August 2008 (World Bank 2008). Given the performance of global equities and other assets even later in 2008 (especially September and October 2008), losses were likely far worse than that estimate for the year as a whole. Despite the fact that asset markets have subsequently reflated, some sold assets at a loss and others remain well below the early 2008 peaks.

Public pension funds are investors with a long-term horizon given the long-term nature of their liabilities, which means that they may not necessarily have had to assume these losses. In 2008/9 new capital accruing to these funds dropped in several countries, meaning that the new funds able to take advantage of cheap valuations may have been limited.

Moreover, many governments will likely have more limited funds available to contribute to these funds for many quarters and years to come. U.S. State govern-ments have been underfunding their pensions for some years now. Pensions funded in whole or in part by individual contributions will receive lower funding given the reduction in hours worked in many countries.

Many of the assessments on optimal asset allocations for individual and corporate pensions are also applicable to public pension plans. Like other pension systems, public pension funds must start by looking at the size and time horizon of their liabilities in order to pick the most optimal asset structure. Despite long-term investment horizons, some do have near term cash flow needs. In the developing world, many countries are trying to play a major role of catch up both in terms of asset management depth and asset value. However, specific assets and the overall investment strategies are under review. In particular like university endowments, some pension funds are reassessing their allocation in high-fee hedge funds, which on average underperformed indices. The recent market performance underscored the importance of ensuring that assets were really diversified against all risks and of carefully picking managers whether they be in house or external.

Asset allocation varies by region should be informed by the risks to the pensions funding streams. As noted by Allianz (2008), many Asian pension funds have maintained a more conservative asset allocation, remaining primarily in cash with 2007-8 despite diversification plans. They thus contributed to the flow of funds into government bonds of domestic and foreign (especially U.S. governments). In the longer term the diversification planned by South Korean, Japanese and Chinese funds could be significant in the Asian market. As noted below, the Chinese fund is already been being used as a vehicle to help develop domestic capital markets including private equity.

In the Middle East and other oil exporting countries, investing in commodities and commodity linked assets might be inadvisable given that the governments other revenues stem from these assets. Too large an allocation to assets linked to the commodities that generate government revenue could overexpose these investors to a prolonged downturn.

Sovereign Pension funds and International Capital Markets

Both government and private pension asset allocation may be contributing to distortions in some investment classes. As argued elsewhere in Bertocchi, Schwartz and Ziemba (2010), the increasing flow of funds into financial instruments to meet corporate pension needs led to a change in investment patterns within the U.S. which reduced funds available for real investment, including in infrastructure and instead towards financial investment. Despite the increase in savings by some sectors of the society in practice most Americans boosted consumption rather than savings.

The desire of pension funds to increase their allocation to real assets, one of several examples in which they have shifted to the ’endowment model’ has led to an increase in pension funds investing in commodity funds, including futures. This inflow of capital into futures markets, rather than necessarily contributing to better price discovery may actually lead to bigger swings both in the prices of the underlying assets and the returns on the funds.

Despite the size of these assets, it is very difficult to isolate the effect of these public investors. In part this reflects their significant but not market moving size. In part their asset allocation decisions are offset by those of other actors. Goldman Sachs noted that increased funds allocated to European equities by European pension funds actually had limited effect on market pricing as adjustments of other investors into other assets likely muted this effect. Yet the change in pension fund allocations, coming at a time when other institutional investors were also moving to a set of common allocations, clearly had an affect.

Governance Issues of public pension funds

The different types of funds present varied governance challenges but all types, which may be linked, tend to be subject to political pressures and political oversight. Recent research on sovereign wealth funds (Harvard 2008) suggests that these entities tend not to get lower than expected financial returns despite the goal to maximize them. The researchers argue that the requirement to invest in domestic economies (something very evident in 2008 and 2009!) restricts their ability to chose the best investments.

Intergenerational borrowing

Governmental saving for retirement or rather public pooling of resources for retirement is a form of intergenerational transfer or lending. In other words, workers contribute today to pay for the needs of current retirees, their descendants will make contributions so that todays workers will have funding. As noted in Bertocchi, Schwartz and Ziemba (2009), this intergenerational transfer is breaking down as demographics have resulted in a lopsided system in which the number of workers supporting each retiree is slipping.

Pension reserve funds appear to be an attractive pool of unallocated or not yet allocated government funds in time of crisis. In some cases the link to future pension needs is more implicit than explicit. Russia's national wealth fund is one example. While its is earmarked for future pension needs it is also been used to fund some of Russia's current spending. Drawing on a pension reserve fund may require fewer legislative changes to draw funds than assets which are already deemed to be pension assets and for which beneficiaries may have some ownership stake. For some countries the calculation seems simple, why not draw on these assets to finance fiscal stimulus today

Countries such as Ireland drew on pension savings to finance today's fiscal packages. Still others are encouraging pension funds to increase their investment in domestic asset markets, perhaps withdrawing funds from abroad - Saudi Arabia's pension fund (GOSI) has been used as an equity stabilization fund, increasing its share of its domestic assets (Ziemba 2009). It has likewise reduced its exposure to deposits in foreign banks and increased those abroad.

These pools of capital and their asset allocation can significantly shape domestic capital markets changing the incentives of investors. Many emerging economies tend to lack domestic institutional investors and often are dominated either by domestic retail investors, large corporations or international investors (depending on how restrictive their investment regime. The introduction of a pension fund or pension reserve fund with a long-term investment horizon could add investors who could at least in theory invest for the longer-term. The sheer number of investment options demanded by those managing public and private retirement could contribute to financial depth in these economies and improve the ability of corporations to seek long-term funding domestically. Doing so would limit some of the exchange rate risks they bear.

Some countries have tried to use their pension funds and other pools of government capital as a tool to lure asset managers and develop their financial sector by entrusting a share of government funds to such asset managers who set up operations domestically. Singapore, for one used assets from the Government Investment Corporation (GIC) as well as pensions to attract asset managers. Coupled with regulatory changes that increase ease of financial operations, Singapore's seed capital did contribute to its asset management industry development.

The different government revenue streams of the government may be correlated. As noted in Setser and Ziemba (2008), countries like the UAE faced a concurrent fall in investment income and oil revenue as equity, corporate bonds and alternative asset returns fell even as the oil price and later oil production reduced revenue. The returns on government savings, as well as resource and tax revenue have fallen even as expenditure demands have increased. The following pressures have emerged even as government pension savings have been in even more demand in a new sort of intergenerational borrowing.

The political leaders and the population that elects them does at time seek to carry out issues of public and even foreign policy. California's two public pension funds (Calpers and Calstrs) have been required to divest of any assets linked to Sudan, going even farther than U.S. sanctions.2 Public pensions funds may thus be a political tool (Steil, 2008). When all were racing to take part in the IPOs of PE firms, the California legislature tried to limit co-investment of Calpers et al. in private equity firms partly owned by sovereign wealth funds whose sponsoring governments had not passed certain human rights requirements. While not passed, this amendment is reflective of political debates surrounding public pension funds, and others that may arise in the future.

Public pension funds, especially those of Norway, Canada, Ireland and others are key activist investors, frequently participating in shareholder activities to improve the performance of their assets. Norway blacklists certain investments that fail to meet ethical and environmental standards. With Norway's fund now the largest single holder of European equities, being left off is significant.

Not only might public pension funds be used as a tool of persuasion, governments might also hope to use their funds to promote economic and especially financial development. In 2007, the Chinese Pension reserve fund was given permission to invest in domestic private equity. Motivations were multi-fold, increase returns on savings to boost the capital available for pensions but perhaps more significantly to provide seed capital for the domestic industry. Other countries such as Singapore have used seed capital from their sovereign funds including pensions to lure foreign asset managers to their jurisdiction, helping to develop the domestic asset management industry. In Singapore's case the combination of financial deregulation, changes that made it cheaper to open a trading operation and the seed capital helped contribute to industrial growth. Others such as South Korea have tried to follow such paths.

Many Asian oil-exporting nations have been allocating investment capital for resource investment. While these investments may respond to long-term resource demands of these energy and metal importers, they also may be good financial investments given the likelihood that the lack of investment may lead to high com-modity prices in the long-term. Yet, as with other sovereign investors, some invest-ments may reflect longer term economic or even strategic goals not just financial returns.

Regional Trends

The following section evaluates recent trends in several key sovereign pension funds, with a focus on those in emerging market economies which might experience the largest growth and largest potential diversification into equities, alternative assets etc in coming years. This survey is not comprehensive but illustrates many of the themes across public pension funds.

Asia

As a group, Asian countries have a significant share of savings earmarked for retirement either through individual savings or those of government pension funds. Many of these could be dedicated to riskier assets over time. However the losses such investments faced in 2008 could defer any such diversification.

The more developed Asian economies like Japan and South Korea have significant retirement savings, quite high on a per capita basis even though these tend to be relatively conservatively managed, Singapore reformed its pension system and now lets its residents choose between a variety of investment fund options. Aging populations create a pension burden for many corporations and imply that a lot of the national wealth is invested in low yielding assets (either domestic and foreign long-term bonds). The less developed economies tend to be less prepared for re-tirement needs though some including China are rapidly trying to respond to the challenge.

Middle East

As a whole the Middle East tends to have low levels of pension coverage, limited to those in the formal sector and especially public sector workers. In general there are different trends across the energy-exporting and energy-importing countries. The latter, tending to be poorer, tend also to have lower national savings as a whole. In fact some countries like Egypt and Lebanon are particularly reliant on the financing from foreign sources. Jordan however is an exception with assets of 36.7% of GDP according to the OECD and ILO.

Some of these undercapitalized systems have benefited from the oil boom. Some countries allocated a share of the surplus to bolster retirement savings. Kuwait used the opportunity of high economic growth and great savings to provide transfers to start putting their pension funds on sounder footing. It made transfers of as much as 10% of GDP in 2008 but subsequently stopped transfers as the oil price fell. It is unlikely to make transfers in 2009 even as withdrawals have increased. Despite the transfers, shortfalls still remain both for national funds as a whole and public sector workers in particular.

Overall, these funds tend to be relatively conservative, more so than the sovereign funds of the same governments, and tend to have little international exposure (ILO, 2009). Several such as the pension funds of public workers in Abu Dhabi have become rather sophisticated drawing on the expertise of internal and external asset managers. Increasingly funds are being invested in foreign bonds and stocks as with other government assets. Some countries like Saudi Arabia actually have fairly established pension funds that are significant holders of domestic equity in addition to foreign currency assets. These though are small as a share of GDP and in comparison to the overall asset of the government.

Europe

Public Pension coverage and asset allocation varies quite widely across Europe which also has well established and large private pension funds. Yet public funds still account for close to a majority of retirement savings, particularly for public sector workers. Most funds have significant exposure to equity markets and a small allocation to alternative assets. As such they are significant participants in European equity markets. There are some exceptions. Spain invests only in fixed income. The largest fund, as a ratio of the size of the economy is in Sweden.

U.S./Canada: Public pensions in the U.S. and Canada tend to be co-funded by payroll deductions from employees, contributions from employers, including the government in the case of public sector workers. U.S. social security continues to be completely invested in US treasury bonds. The political debate on the underfunded liabilities related to social security and Medicare will revive in coming years but for now concerns have taken a back seat to shorter term financing worries. By contrast the public funds of individual states for their public employees have tended to increase their allocation to equities and other riskier assets to make up for funding shortfalls as cash-strapped regional governments held back on allocations. Some investments have been sold at a loss, especially property holdings and private placements relied indirectly on leverage.

Conclusion

By virtue of their increase in assets and diversification to increase their risk-adjusted return, public pension funds have become a more significant investor in global, regional and national capital markets. The creation of reserve funds by both developed and emerging economies to help meet the retirement funding shortfall has boosted the size of these assets. In 2009, these funds are trying to process the lessons of the credit crisis and global asset market correction. Several may take the lesson to increase the share of liquid assets in their portfolios to have funds available should the government or beneficiaries claim funds. Moreover given the political pressures inherent in investment losses, some sovereign investors may further try to minimize losses.

Thus, sovereign pension funds must be seen as one of several pools of capital managed by governments. Despite different goals and time horizons, many of these varied types of sovereign capital are being managed with a similar asset allocation. Over time, should pension funds continue to attract assets, their asset allocation might adjust slightly. In particular, given their long-term horizon, it could be in the interest of financial markets, pension beneficiaries and other citizens, if sovereign pension funds filtered more investments into real investment, particularly infras-tructure. Not only might such investment lead to long-term economic benefits but it should also bring a financial return which should hold its value even in the case of rising inflation.

Update: Since writing this in 2009, the retirement funding gap has only become more acute as governments have tended to cut back on transfers to pensions as part of prioritizing current spending needs. These funds are but some of the sovereign managed capital, what is different is that they tend to have implicit if not explicit liabilities.

1Edited from Wilmott, September 2009.

2Author's note: In early 2013, these funds were considering divesting from gun manufacturers.