A Risk Arbitrage Convergence Trade: The Nikkei Put Warrant Market of 1989—90

Dr. Thorp and I, with assistance from Julian Shaw (then of Gordon Capital, Toronto, now the risk control manager for Barclays trading in London), did a convergence trade based on differing put warrant prices on the Toronto and American stock exchanges. The trade was successful and Thorp won the over $1 million risk adjusted hedge fund contest run by Barron's in 1990. There were risks involved and careful risk management was needed. What follows is a description of the main points. Additional discussion and technical details appears in Shaw, Thorp and Ziemba (1995).

This edge was based on the fact that the Japanese stock and land prices were astronomical and very intertwined, see Stone and Ziemba (1993) for more on this relationship.

The historical development leading up to the NSA put warrants

•Tsukamoto Sozan Building in Ginza 2-Chome in central Tokyo was the most expensive land in the country with one square meter priced at ¥37.7 million or about $279,000 U.S. at the (December 1990) exchange rate of about ¥135 per U.S. dollar.

•Downtown Tokyo land values are the highest in the world, about $800 million an acre.

•Office rents in Tokyo are twice those in London yet land costs 40 times as much

•The Japanese stock market, as measured by the Nikkei stock average (NSA), was up 221 times in yen and 553 in dollars from 1949 to the end of 1989.

•Despite this huge rise, there had been twenty declines of 10% or more in the NSA from 1949 to 1989. The market was particularly volatile with two more in 1990 and two more in 1991. Stocks, bonds and land were highly levered with debt.

•There was a tremendous feeling in the West that the Japanese stock market was overpriced as was the land market. For example, the Emperor's palace was reputed to be worth all of California or Canada. Japanese land was about 23% of world's non-human capital. Japanese PE ratios were 60+.

•Various studies by academics and brokerage researchers argued that the high prices of stocks and land were justified by higher long run growth rates and lower interest rates in Japan versus the US. See for example, Ziemba and Schwartz (1991) and French and Poterba (1991). However, similar models predicted a large fall in prices once interest rates rose from late 1998 to August 1990, see Chapters 2 and 21.

•Hence both must crash!

•There was a tremendous feeling in Japan that their economy and products were the best in the world.

•There was a natural trade in 1989 and early 1990

— Westerners bet Japanese market will fall

— Japanese bet Japanese market will not fall

Various Nikkei put warrants which were three-year American options were offered to the market to fill the demand by speculators who wanted to bet that the NSA would fall.

NSA puts and calls on the Toronto and American stock exchanges, 1989–1992

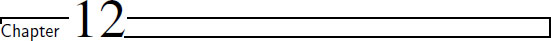

The various NSA puts and calls were of three basic types, see Table 12.1.

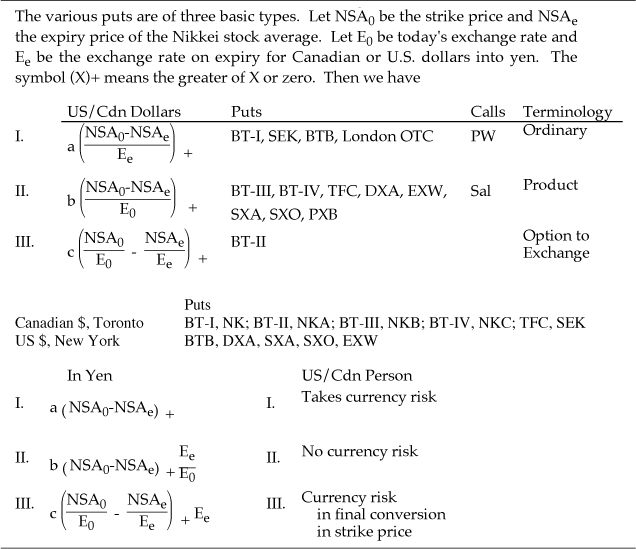

Our convergence trades in late 1989 to early 1990 involved:

(1)selling expensive Canadian currency Bankers Trust I's and II's and buying cheaper US currency BT's on the American Stock Exchange; and

(2)selling expensive Kingdom of Denmark and Salomon I puts on the ASE and buying the same BT I's also on the ASE both in US dollars. This convergence trade was especially interesting because the price discrepancy was based mainly on the unit size and used instruments on the same exchange.

Table 12.2 describes this. We preformed a complex pricing of all the warrants which is useful in the optimization of the positions size, see Shaw, Thorp and Ziemba (1995). However, Table 12.2 gives insight into this in a simple way. For example, 9.8% premium year year means that if you buy the option, the NSA must fall 9.8% each year to break even. So selling at 9.8% and buying at 2.6% looks like a good trade.

Some of the reasons for the different prices were:

•Large price discrepancy across the Canada/U.S. border

•Canadians trade in Canada, Americans trade in the U.S

•Different credit risk

•Different currency risk

•Difficulties with borrowing for short sales

•Blind emotions vs reality

•An inability of speculators to properly price the warrants

Table 12.1:NSA Puts on the Toronto and American Stock Exchanges, 1989–1992

Table 12.2:Comparison of Prices and Premium Values for Four Canadian and Three U.S. NSA Put Warrants on February 1, 1990

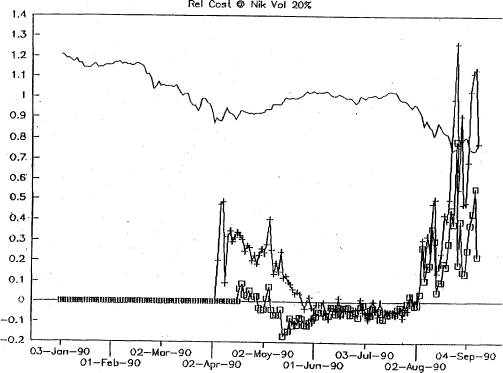

I's were ordinary puts traded in yen. II's were currency protected puts (often called quantos). III's were the Nikkei in Canadian or US dollars. The latter were marketed with comments like: you can win if the Nikkei falls, the yen falls or both fall The payoffs in yen and in US/Cdn are shown in Table 12.1. A simulation in Shaw, Thorp and Ziemba (1995) showed that for similar parameter values, I's were worth more than II's, which were worth more than III's. But investors preferred the currency protected aspect of the II's and overpaid (relative to hedging that risk separately in the currency futures markets) for them relative to the I's. Figures 12.1 and 12.2 show the two convergence trades.

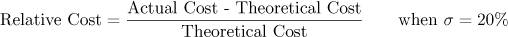

is plotted rather than implied volatility since the latter did not exist when there were deep in the money options trading for less than intrinsic as in this market. Fair value at 20% NSA volatility and 10% exchange rate volatility is zero on the graph. At one, the puts are trading for double their fair price. At the peak, the puts were selling for more than three times their fair price.

Fig. 12.1Relative costs of BT-I, BT-II and BTB NSA put warrants with NSA volatility of 20% and exchange rate volatility of 10%, 17 February 1989 to 21 September 1990. Relative deviation from model price = (actual cost - theoretical value)/(theoretical value). Key: (+) BT=I, type I, Canadian,  BT-II, type III, Canadian and (∆) BTB type I, US and (-) normalized Nikkei

BT-II, type III, Canadian and (∆) BTB type I, US and (-) normalized Nikkei

The BT-I's did not trade until January 1990 and in about a month the Canadian BT-I's and BT-II's collapsed to fair value and then the trade was unwound. The Toronto newspapers inadvertently helped the trade by pointing out that the Canadian puts were overpriced relative to the US puts so eventually there was selling of the Canadians, which led to the convergence to efficiency. To hedge before January 1990 one needed to buy an over the counter put from a brokerage firm such as Salomon who made a market in these puts. The NSA decline in 1990 is also shown in Figure 12.1. Additional risks of such trades is being bought in and shorting the puts too soon and having the market price of them go higher. We had only minor problems with these risks.

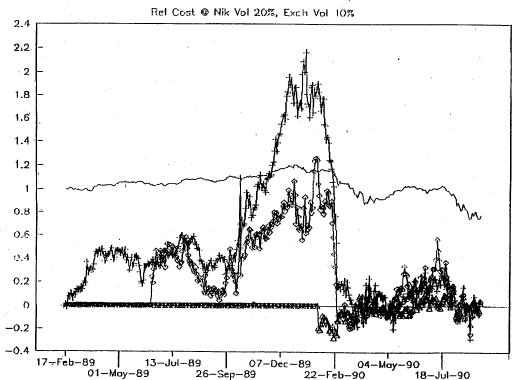

Fig. 12.2Relative costs of US type I (BTB) versus US type II (DXA, SXA, SXO) NSA put warrants with NSA volatility of 20%, January to September 1990. Key: ([]) BTB, type I, 0.5 NSA, (+) avg DXA, SXA, SXO, type II, 0.2 NSA, and, (-) normalized Nikkei

Fair value at 20% NSA volatility and 10% exchange rate volatility is zero on the graph. At one the puts are trading for double their fair price. At the peak, the puts were selling for more than three times their fair price.

For the second trade, the price discrepancy lasted about a month. The market prices were about $18 and $9 where they theoretically should have had a 5 to 2 ratio since one put was worth 20% and the other 50% and trade at $20 and $8. These puts were not identical so this is risk arbitrage not arbitrage. The discrepancy here is similar to the small firm, low price effect (see Ziemba, 2012a). Both puts were trading on the American stock exchange.

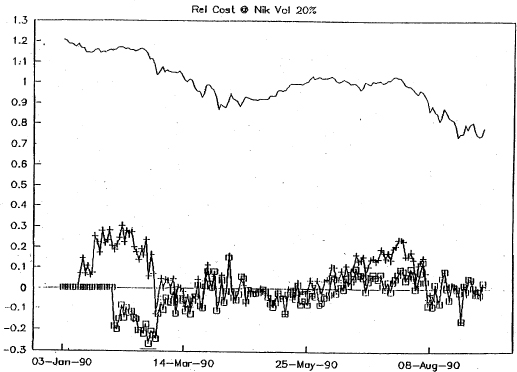

There was a similar inefficiency in the call market where the currency protected options traded for higher than fair prices; see Figure 12.3. There was a successful trade here but this was a low volume market. This market never took off as investors lost interest when the NSA did not rally. US traders prefered Type II (Salomon's SXZ) denominated in dollars rather than the Paine Webber (PXA) which were in yen.

The Canadian speculators who overpaid for the put warrants that our trade was based on made $500 million Canadian since the NSA's fall was so great. A great example of the mean dominating! The issuers of the puts also did well and hedged their positions with futures in Osaka and Singapore. The losers were the holders of Japanese stocks. We did a similar trade with Canadian dollar puts traded in Canada and hedged in the US. The difference in price (measured by implied volatility) between the Canadian and US puts stayed relatively constant over an entire year (a gross violation of efficient markets). The trade was also successful but again like the Nikkei calls, the volume was low.

Fig. 12.3 Relative costs of Paine Webber and Salomon NSA call warrants with NSA historical volatility of 20%, April to October 1990. Relative deviation frommodel price = (actual cost - theoretical value)/(theoretical value). Key: (+) PXA,, (+) SXZ and (–) normalized Nikkei