What Signals Worked and What Did Not, 1980-2009, Part II1

Continuing the series of articles reviewing prediction signals in current market conditions

This chapter is the second in a series of three columns that review various prediction signals and how they preformed for various asset classes but focusing on the equity markets. In many but not all cases the signals such as the bond-stock earnings yield differential, my T- measure of relative put and call options prices, Buffett's stock market to GDP measure, the January first five days and all o January indicator, sell in May and go away, and the VIX volatility index were very useful and accurate in predicting subsequent market dechnes and rises. Also some s hort term anomaly indicators such asoptions expiry, turn-of-the-month and year, holidays , etc. have had predictive value.

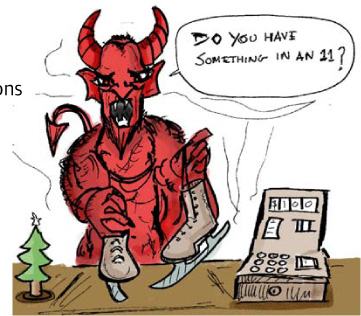

As I write this in June 2009 the S&P500 has had a slow but steady climb from its March 666 iow to the 940 area. Several times the market has reached 950 only to be pushed back each time. But the sense is that there is less bad news, a so-called second derivative effect, and uince the stock market is supposed to predict; six months ahead, it is rising to forecast better times. Nobel laureate Paul Krugman and others have suggested that the US recession (beginning signaled by two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth) will end in the fall of 2009. George Soros said in late June that the worst is over. But the recovery will be slow and painful as Joe Stiglitz and Nouriel Roubini predict and as articulated in the recent Maudlin (2009b) column. Savings rates have increased dramatically which, while cutting into spending, is a harbinger of a new normal as also discussed by El-Erian (2008). Oil prices have doubled since their bottom of $32 in early 2009 and are much higher, over $100, in March 2012. The current $72 is about halfway back to the summer 2008 high of $147 per barrel. Also, as a sign of better growth is the steepening of the yield curve with the 10-year T-bond now near 4% versus 3% a month or so ago. The graphs in Figure 24.1 show this progress.

Fig. 24.1Indicators of improving economic environment

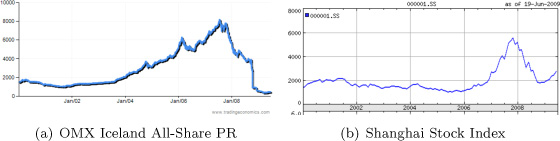

The usually reliable bond-stock yield model was of great help in 2006-9 for the Iceland, Chinese and US markets. In Ziemba and Ziemba (2007) we studied these latter two markets and concluded when we went to press in the fall of 2007 that they were close to the danger zone thus predicting a stock market crash but not quite. But in 2008 a further rise in 5-year bond rates (the long bond in both of these countries) plus a drop in earnings led to the danger signal and the subsequent crash. Figures 24.2a,b show this. This analysis, which is based on Lleo and Ziemba (2012), is discussed in Chapter 21.

In the US there was a sell signal as of June 14, 2007 based on high interest rates relative to trailing stock earnings. The ensuing 2007-2009 crash was credit and confidence related due to a massive build up of derivatives including those based on toxic assets in real estate. The Fed lowered the interest rates and the long bond rate became artificially low. The endogenous creation of liquidity wiped out the efforts of the Fed to control the interest rates and thereby the money supply.

Since June 14, 2007 the BSEYD measure has not signaled an additional crash. The measure must be about +3 to be in the danger zone. That would take a huge increase in the 10-year bond rate plus a big PE expansion (higher stock prices and/or greatly lower earnings). Neither seems likely. Even now with earnings dropping dramatically the measure is still not in the danger zone.

Fig. 24.2 Stock price indices for Iceland and China, January 2000 to June 19 (2009)

In late 2008 and the first few months of 2009, S&P500 earnings and forecasts for 2008 and 2009 were continually dropping. Table 21.9 from Maudlin (2009a) shows this dramatic decline. Even with these low earnings, the model was still not in the danger zone but we did have the June 14 danger signal which presaged these declines. Interest rates have dropped dramatically with short term rates near zero. However access to these low posted rates is not readily available. It is the liquidity crisis that has created a real interest rate that is dramatically high and approaching infinity as credit for many is totally unavailable, credit card companies are denying previous credit limits and recalling credit cards.

What went wrong? Indeed we have been in a period of declining interest rates. The decades before the crash and the crash itself were transitional economic times. While consumption spending is normally a large part of GDP, it had become even more significant as people withdrew equity from their homes, treating them as ATMs. This both fueled the economy and at the same time planted the seeds for the crash as clearly this level of spending was unsustainable especially once housing prices began to soften. During the same period, there was a rapid growth in derivative products that created a huge pool of liquidity, again, unsustainable. The way out of this crisis will be a return to more normal debt instruments that sustain the real economy. Let's look at the history of this crisis.

The subprime crisis and how it evolved

“Let's hope we are all wealthy and retired by the time this house of cards falters.” –Internal email, Wall Street, 12/15/06

In 2004 an estimated $900 billion dollars was withdrawn from home equity through refinancing.2

In the days following September 11, 2001, with the attacks on US soil and the markets very weak, Fed chairman Alan Greenspan said he was extremely worried about the after effects on the US economy. So five day later, when the stock market reopened, the first of a number of interest rate cuts was made. In 2002 President George W Bush said “The goal is, everybody who wants to own a home has got a shot at doing so.” He also referred to the homeownership gap that “three-quarters of Anglos own their homes, and yet less than 50% of African Americans and Hispanics own homes.” (at a speech at HUD, June 18, 2002). At the same time he linked home ownership to national security.

Freddie Mac and Fanny Mae created the secondary mortgage market and between them insured about half the mortgages. Originally these had been made under strict qualifying procedures but they came under pressure by the industry and government policy to loosen their standards. Orange county entrepreneurs wanted a way to circumvent these rules and create a profitable business that was unregulated. They invented the concept of subprime mortgages where anyone could get a loan at a time when Freddie and Fanny were in some trouble. Actual incomes and assets were not checked and largely inflated. Bad credit and no assets (or a lot of debt and liabilities) did not matter. What made this work was a great interest from Wall Street firms to package these mortgages and have them AAA rated so they were investment grade. Then the Wall Street firms could sell these CMOs (collateralized mortgage obligations) around the world. The rating agencies were paid by the firms selling the CMOs not the purchasers. The rating agencies were eager to have the business and the repeat business. Since it was assumed that house prices could not fall - they had not fallen since 1991-2 — this seemed safe. Around the world, investors, a bit greedy to get higher returns were sucked into buying these securities. One example is Narvik, Norway, a small town 150 miles above the Arctic circle. They bought enough of these assets from a representative of Citi Bank through an Oslo representative to lose most of the town's assets.

Meanwhile, house prices roared higher and higher around the world far outstrip-ping income growth. Buyers with no money were able to buy houses then refinance them and cash out the gains to upgrade their homes or just to spend the money. Indeed a huge percent of US consumption in 2003-2007 came from this source. Houses were assumed to rise in value by 6-8% yearly forever. But a bubble was forming and house prices in the US peaked in 2005/2006.

The packaging of the mortgages into AAA rated CMOs and later CDO (collateralized debt obligations which include any asset with a future income stream) continued.

From 2002-2006 as a result of the housing bubble so many speculators gained by buying extra houses on margin. In 2007-2009 the declines in the US hurt such speculators hard and many went into receivership. Indeed over 10 million houses in the US in January 2009 were under water in the sense that their mortgages exceed their current market value.

For the period December 1, 2007 to November 30, 2008 prices in the 20 areas fell a record 18.2% with November 2008 adding a 2.2% decline. The housing market continues to suffer from a large supply of unsold homes, tighter lending standards and a record number of foreclosures. The 10 metro regions also fell 2.2% in November for a yearly drop of 19.1%. The composite 10 and 20 metro regions peaked in mid 2006 and since then (to Feb 2009) have fallen 32% and 30%, respectively.

Areas that had large increases had large falls. This includes many cities in California, Nevada and Florida. From March 2008 to March 2009, for example, San Francisco fell 43%. There were similar drops in San Jose and other areas in California.

The housing price declines have left more than 20% of US homeowners owing more on their mortgages than their houses are worth by the end of Q1:2009. That represents 20.4 million households, up from 16.3 million in Q4:2008. That is 21.9% of all homeowners, up from 17.6% Q4:2008 and 14.3% Q3:2008. On the one hand, the falling home prices are making housing more affordable for first-time buyers and other who have had difficulty getting into the market. On the other hand, the fall in home equity has cut off the ability of homeowners to use their homes like an ATM as refinancing is harder so they cannot take advantage of the low interest rates. The regions with the highest percentage of homes underwater are shown in Table 24.1.

Table 24.1: Metropolitan regions with the highest percentage of homes with negative equity in Q1:2009. Source: Simon and Hagerty (2009)

|

Region |

% Underwater |

|

Las Vegas, NV |

67.67 |

|

Stockton, CA |

51.51 |

|

Modesta, CA |

50.50 |

|

Reno, NV |

48.48 |

|

Vallejo-Fairfield, CA |

46.46 |

|

Merced, CA |

44.44 |

|

Port St Lucie, FL |

43.43 |

|

Riverside, CA |

42.42 |

|

Phoenix, AZ |

41.41 |

|

Orlando, FL |

41.41 |

|

US average |

21.9 |

With such a large number of households underwater, it will be hard to get a consumer led recovery. In the UK, the declines are similar, with the year on year values down about 20% for high end properties in London during 2008-9.

The lending organizations sold off the mortgages and they were cut and diced and bundled into packages like CMOs and CDOs and sold to others who had trouble figuring out what is in them but look at the rating agency's stamp of approval. A triple A rating was desirable for sales of these derivative securities.

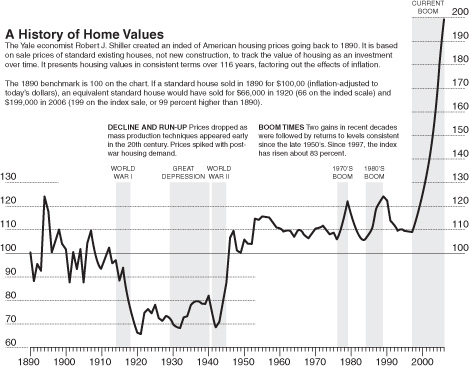

Figure 24.3, starting in 1890, shows the buildup to overpriced areas in 2004- 5 that led to the drop now that is shown in Figure 20.1b. There have been 12 consecutive months of negative returns. The 10-city, 20-city decline and 10-city composite all declined. Case-Shiller and others predict up to a 25-35% drop in prices from the peak in 2005-6, see Figure 24.3.

Fig. 24.3 A history of home values. Source: Nouriel Roubini (2006)

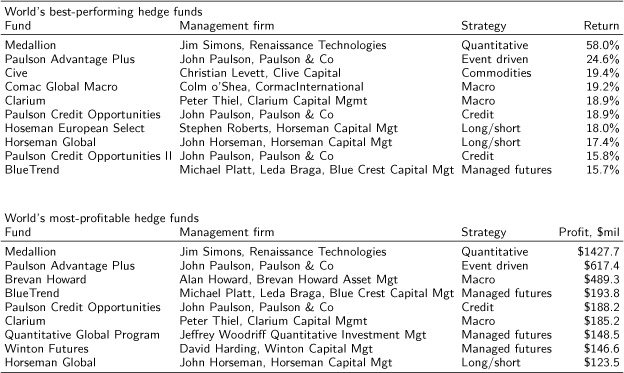

Business was good. Even pizza deliverers became, with no training, mortgage brokers. There was no license, so no training, involved. Once they started arranging the mortgages, they quickly began earning $20,000/month and they soon were buying expensive cars. One Southern California Lebanese immigrant with a 3rd grade education had a firm selling Mercedes to his loan officers. At the peak in 2005-6, he was making $5 million/month. He had money to burn. An example was a movie featuring his girlfriend in which two Ferrari's, one worth $1/2 million and the other worth a full $1 million, were destroyed as part of the filming. When prices of houses and real estate stocks fell starting in late 2005, the defaults multiplied, the CMOs and CDOs dropped sharply in value. One hedge fund trader, David Bass in Texas, saw this coming and made 600% on his investment, some $1 billion, by buying insurance on these instruments which rose sharply in value and was piad off as the house prices fell. Of course, John Paulson was a big player in these and related markets in his various funds, making 1000% in 2007; see Table 24.2 for some 2008 results.

Another factor fueling this in 2004 was Greenspan saying that the market needs “new products for mortgage loans”. These included adjustable rate mortgages with low or no interest payable in the first year or two with the interest added to the loan value. Then with higher interest, higher loans and declining house values, the situation became more difficult and led to millions of mortgage defaults. This destroyed the American dream of owning a home with other people's money.

Table 24.2: Hedge Funds, January to September 2008. Source: Bloomberg

Greenspan still insists that such bubbles are just a part of human behavior and will happen again and again and there was nothing the Fed could have done to prevent it. And it would be bad politics to stop home ownership. He admits now that he was shocked when he learned that 20% of all US mortgages were subprime and that he, with some math and economic training and a staff of 200 with many PhDs could not understand many of the CDO products which made use of option experts trained at leading math finance and other departments. Wow!!

Yet the issue was that there was a gap in regulations and application of prudence in lending. In Canada and many other countries, you cannot get these extreme subprime mortgages and consequently there have not been such a fall in house prices nor as many defaults. Also in Canada unlike the US non-recourse loans, borrowers are at risk on all their assets not just the property that's being mortgaged.

Household and government debt

While US house prices surged from 2000 to 2007, household debt was also surging. Household debt went from 60% of disposable income (after tax) in 1985 to 80% in the early 1990s and soared to 120% in 2007. In the years from 2001 to 2004 about 40% rewrote their mortgages, 25% extracted equity in the process. The under 30s and the over 63s extracted lower rates of equity (15% and 18% respectively). The funds were used for consumption (10.5%), payment of other debt (23.5%), home improvement (32.2%), and investment including stock market (33.8%). In sum, the value of primary residences increased $4,164 billion, and $783 billion was extracted from equity and $267 billion went into consumption. House values increased another $6.4 trillion from 2004 to 2006, if the same ratios held then about $410 billion went into consumption. For the households that extracted equity and then consumed it, their net worth did not increase, but when the bubble burst they have lost net worth as their assets have declined in value while their debt has increased. Up to 2008 those workers near retirement that remortgaged and extracted wealth had lost 14% of net worth just from this shift, in addition they likely lost a lot on their retirement savings. They will have the hardest time recovering retirement savings (Munnell and Soto, 2008).

The US and UK households have very high debt compared to disposable income which has been steadily rising from 1990 to 2008. This is at the heart of the housing declines in both countries. Canada and the euro zone have much less debt which is partly a result of much tighter standards for mortgages and other lending. Banks in the US and the UK basically would lend money to anyone for real estate transactions given their false forecast that prices would continue to rise. Then the decline in real estate values had a much bigger effect in these countries. Table 24.3 shows the government debt as a percentage of GD in 2008. Japan and Italy have the highest debt ratios. But the citizens of Japan have large savings which tempers the risk there. Italy like the UK is in serious financial trouble. The US has one big advantage with its government debt - in US dollars - in very high demand around the world so their constant printing of money, while dangerous, is less so than other countries who have debt in other currencies and thus must earn foreign currency to repay it.

Table 24.3: G7 debt to GDP ratios, 2008. Source: Globe and Mail, January 22 (2009)

|

Canada |

22% |

|

Britain |

33% |

|

France |

36% |

|

Germany |

43% |

|

U.S. |

46% |

|

Italy |

87% |

|

Japan |

88% |

Some 44% of US households were participating in the financial markets in 2007, up from 29% in 1994 representing 88 million individual investors.

More than half of these investors are 45 years old or older, and a third of this group (approximately 17.6 million people) are older than 65, so they have limited opportunities to earn their back to their retirement savings given the 2007-2009 declines of about 50% in equity markets.

Favoring the financial sector: evaluating the policy responses

In the last 25 years, the deregulated finance sector grew as the real production sector was in the decline in the US and in the UK. Profits came to be concentrated in this sector, and indeed it was very innovate with securitization, interest-rate swaps and credit default swaps among other instruments. The effect of this can be seen for the growth in the share of corporate profits going to the financial sector. From 1973 to 1985, this sector earned about 16% of the corporate profits. In the 1990s their profit share ranged from 21% to 31% and in the most recent decade this escalated to 41% of all corporate profits. Concomitant with this increase in profits came rising incomes. From 1948 to 1982 average compensation in this sector was about average for the economy between 99% and 108% of the average for all domestic private industry. But by 2007 it reached 181% (see Johnson, 2009).

In the global economic crisis there have been several phases and various responses by the US Federal Reserve, the US Treasury Department and the Federal government and similar bodies in the UK and elsewhere. So far to early April 2009, these policy responses of monetary easing (open market operations now referred to as quantitative easing) and fiscal spending have had some success but that has been limited. Unfortunately, the policy response has to a large part been to continue to favor finance over real production. Instead of nationalizing the banks and cleaning them up, money has been allocated to them to shore them up.

In part this is a reflection of the structure of the Fed, the US central bank. The seven member board of governors is appointed by the president with the approval of the Senate. The boards of the twelve independently incorporated regional banks are composed of three members appointed by the Fed board and six elected by the member banks. So the chairman of, say, the NY Fed owes the position to the banks in the region and routinely consults with them. In May, 2007 in a speech to the Atlanta Fed, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner said that “the financial innovations had improved the capacity to measure and manage risk” and that “the larger global financial institutions are generally stronger in terms of capital relative to risk” (quoted in Becker and Morgenson, 2009). At this point, New Century Financial had already filed for bankruptcy due to sub-prime losses and by July Fed chair Ben Bernanke warned that the US sub-prime crisis could cost up to $100 billion.

Geithner, encouraged by Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase, was proposing new looser standards for the banks. The problem, according to Callum McCarthy, a former British regulator, was that “banks overestimated their ability to manage risk, and we believed them” (Becker and Morgenson, 2009).

Nobel Laureate and Columbia University Professor Joseph Stiglitz among other economists has expressed the concern that this relationship has led to a regulatory philosophy shaped by and shared with the industry itself. This led a bailout that was designed to get a lot of money into the banks to shore them up without necessarily considering the risks to the public at large (Becker and Morgenson, 2009).

A variety of regulatory changes have been proposed by economists, politicians, journalists, and business leaders to minimize the impact of the current crisis and prevent recurrence. However, as of April 2009, many of the proposed solutions have not yet been implemented. These include (from Wikipedia) the following excellent suggestions:

•Ben Bernanke: Establish resolution procedures for closing troubled financial institutions in the shadow banking system, such as investment banks and hedge funds.

•Joseph Stiglitz: Restrict the leverage that financial institutions can assume. Require executive compensation to be more related to long-term performance. Re-instate the separation of commercial (depository) and investment banking established by the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933 and repealed in 1999 by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.

•Simon Johnson: Break-up institutions that are “too big to fail” to limit systemic risk.

•Paul Krugman: Regulate institutions that “act like banks” similarly to banks.

•Alan Greenspan: Banks should have a stronger capital cushion, with graduated regulatory capital requirements (i.e., capital ratios that increase with bank size), to “discourage them from becoming too big and to offset their competitive advantage.”

•Warren Buffett: Require minimum down payments for home mortgages of at least 10% and income verification. The Canadian banks do this and its more than 10% in almost all loans.

•Eric Dinallo: Ensure any financial institution has the necessary capital to sup-port its financial commitments. Regulate credit derivatives and ensure they are traded on well-capitalized exchanges to limit counterparty risk.

•Raghuram Rajan: Require financial institutions to maintain sufficient “contin-gent capital” (i.e., pay insurance premiums to the government during boom periods, in exchange for payments during a downturn.)

•A. Michael Spence and Gordon Brown: Establish an early-warning system to help detect systemic risk.

•Niall Ferguson and Jeffrey Sachs: Impose haircuts on bondholders and coun-terparties prior to using taxpayer money in bailouts.

•Nouriel Roubini: Nationalize insolvent banks.

In Chapter 25, I look into the results of other signals to assess what worked and what did not.

1 Edited from Wilmott, July 2009.

2This section utilizes the CNBC TV program hosted by David Faber called “A House of Cards” for much information on this episode.