On April 25, 1846, Mexican soldiers splashed across the Rio Grande and attacked a small group of American troops. Sixteen Americans were killed, and the rest captured. “Hostilities have commenced,” General Taylor wrote to President Polk. When the letter reached Washington (it took a couple of weeks), Polk immediately went to Congress to demand a declaration of war: “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States,” he said, “has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil.”

Had the shooting really started in American territory? Some members of Congress didn’t think so. “That soil was not ours,” said a little-known House member from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln. To Lincoln, it looked like Polk had purposely sent Americans soldiers into the disputed territory in order to spark a war with Mexico. The war would give the United States an excuse to capture the land Mexico had refused to sell. Pretty rotten, thought Senator Alexander Stephens of Georgia: “The principle of waging war against a neighboring people to compel them to sell their country, is not only dishonorable, but disgraceful.”

Polk objected, pointing out that Mexico had started the shooting. He had always wanted peace with Mexico, he insisted. His opponents joked that what Polk really wanted was not peace with Mexico, but a piece of Mexico.

Either way, the public was on Polk’s side. American soldiers had been attacked, and there was strong support for war. Congress voted to declare war on Mexico in May 1846. Thousands of Americans rushed to volunteer for military service.

As for Abraham Lincoln, he soon heard from angry voters back home, who said his opposition to the war was pretty much an act of treason. One Illinois newspaper actually called him “a second Benedict Arnold.” That was the end of Lincoln’s political career, experts said.

“Mexico should fight to the end,” declared a newspaper in the Mexican city of Nuevo Leon. “As long as there is one man remaining, he should go and fight the unjust invaders.”

The problem with this plan: the Mexican army was in awful shape. Most Mexican soldiers had very little training and terrible equipment, including old-fashioned muskets sold to them by the British (left over from wars Britain had fought thirty years ago). The army could not even have survived without soldaderas, women who traveled along with the troops and did work the army should have done: cooking, making uniforms, caring for the sick and wounded.

Another serious problem was that the Mexican army was led by General Antonio López de Santa Anna, the self-proclaimed genius who had lost Texas. Santa Anna was good at talking tough, not so good at actual fighting. When his army faced Americans at the Battle of Buena Vista in early 1847, Santa Anna demanded that the Americans surrender in order to save themselves.

“Tell Santa Anna to go to [censored]!” barked Zachary Taylor. Then Taylor turned to a staff member and said: “Major Bliss, put that in Spanish, and send it back.”

Bliss put Taylor’s main idea into slightly more polite language: “I beg leave to say that I decline acceding to your request.”

Santa Anna attacked, lost five times more men than the Americans, and declared victory. Then he retreated. In a series of short, brutal battles in the spring and summer of 1847, the American army continued slashing its way toward Mexico City.

Meanwhile, the war with Mexico gave Polk an excuse to do something he’d wanted to do anyway—send American troops to capture California.

Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo woke suddenly on the morning of June 14, 1846, startled by the sounds of shouts and horses. “I looked out of my bedroom window,” Vallejo said. “To my great surprise, I made out groups of armed men scattered to the right and left of my residence.”

As Mexico’s military commander in northern California (and uncle to the young pioneer Guadelupe Vallejo), Vallejo had always been welcoming to American immigrants. He often invited newcomers to stay at his large ranch in Sonoma and helped them settle in California. But that did him no good when armed Americans banged on his door.

“My wife advised me to try and flee by the rear door,” Vallejo remembered. “But I told her that such a step was unworthy and that under no circumstances could I decide to desert my young family at such a critical time.” He jumped into his general’s uniform and opened his door. “The house was immediately filled with armed men,” he said.

These weren’t Polk’s soldiers—just regular guys with guns, wearing greasy clothes and very dirty hats. “They were about as roughlooking a set of men as one could well imagine,” admitted Robert Semple, one of the Americans.

Too polite to say what he was really thinking, Vallejo asked, “To what happy circumstances shall I attribute the visit of so many exalted personages?”

Shouting all at once, the Americans declared that they were there to arrest Vallejo. They were seizing California from Mexico! (And while they were at it, they seized Vallejo’s brandy, and downed it in quick gulps.)

Then the Americans marched to the town plaza in Sonoma, declared California to be an independent republic, and raised a homemade flag on which they had painted a grizzly bear. Well, it was supposed to be a bear.

“The bear was so badly painted,” Vallejo said, “it looked more like a pig than a bear.”

Anyway, the key point is that these Americans had heard that the United States was at war with Mexico. They decided it was a good time to seize California for their country.

A few weeks later, the American soldiers and sailors sent by President Polk started arriving. They took control of California for the United States.

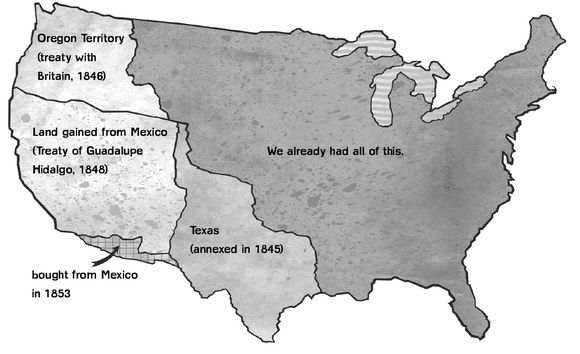

In September 1847 American soldiers captured Mexico City. Having lost the war, Mexican leaders were forced to accept the same basic deal they had angrily rejected two years before. In the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico gave up nearly half its territory, including the disputed land in Texas, all of California, New Mexico, and the rest of what is now the southwestern United States. The United States paid Mexico fifteen million dollars.

Now the West is West: U.S. in 1848

Now all the land we think of as the West today was part of the United States.

While all this was going on, more and more Americans were showing up in the West. Followers of the new Mormon religion even established their own western trail. After getting violently chased out of towns in Missouri and Illinois, the Mormons were looking for a new place to settle. The Mormon leader Brigham Young read about the Great Salt Lake Valley—a giant salty lake surrounded by deserts. It sounded like a good place to be left alone.

In the spring of 1847, Young and his followers established the Mormon Trail, a 1,300-mile route from Illinois to what is now Utah. When the travelers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, they were not impressed. “A paradise of the lizard, the cricket, and the rattlesnake,” one settler said. That was fine by Brigham Young.

“I want hard times, so that every person that does not wish to stay for the sake of his religion will leave.”

Brigham Young

The Mormon settlers began irrigating fields, planting crops, building homes, and laying out the streets of a new town. It took them just a few years to turn Salt Lake City into the second-largest city west of Missouri (only San Francisco was bigger).

Meanwhile, thousands of other Americans were heading west, most of them on the Oregon Trail. When they arrived in Oregon, many travelers stopped to rest at the home of Narcissa and Marcus Whitman—remember them? They’re the missionaries who had settled in Oregon and taken in the orphaned Sager children.

The Cayuse and other Indians of the region watched this migration with growing alarm. Ten years before, Cayuse leaders had invited the Whitmans to settle on their land. The Whitmans told them they were there to teach and help the local people. But now the Whitmans were using their house as a welcome station for huge groups of white settlers. This was not at all what the Cayuse had agreed to. “The poor Indians are amazed at the overwhelming numbers of Americans coming into the country,” Narcissa Whitman wrote.

They had good reason to be amazed, and angry too. The new settlers not only grabbed big chunks of land, but they also brought diseases that had not existed in that part of the world. Measles, for example, was not very dangerous for people of European background. They had developed natural defenses to it over many centuries. But when American settlers brought measles to Oregon in 1847, the disease quickly killed half the people in many Cayuse villages—and nearly all of the children.

Unable to escape from this nightmare, some Cayuse began

wondering, How come Marcus Whitman, who is a doctor, is able to cure most of the white children, while our own children continue to die? A rumor started spreading that the Whitmans were purposely using the disease to wipe the Cayuse out.

“The disease was raging fearfully among the Indians, who were rapidly dying,” said Catherine Sager. “I saw from five to six buried daily.” Four years earlier Catherine had watched her parents die on the Oregon Trail. Now she was thirteen and in for another horrible shock.

The morning of November 29 was foggy and cold, Catherine Sager remembered. She was at home with the Whitmans, helping to care for sick children. There was a sudden burst of banging on the front door.

Outside, pounding with his fists, was a Cayuse chief named Tiloukaikt, along with several other Cayuse men. Tiloukaikt had just seen three of his children die of measles. Now he was shouting for Dr. Whitman to let him in and give him medicine for other sick children.

Marcus Whitman let the men into the kitchen. Catherine, who was in the living room with Narcissa Whitman, heard angry yelling. “Suddenly there was a sharp explosion,” she said, “a rifle shot in the kitchen, and we all jumped in fright.”

Moments later a girl named Mary Ann stumbled into the room.

“Did they kill the doctor?” Narcissa cried.

Panting and pale with shock, Mary Ann managed to say “Yes.”

“My husband is killed and I am left a widow!” wailed Narcissa.

Through the living room window, Catherine could see Cayuse men attacking other settlers in nearby buildings. “Then a bullet

came through the window, piercing Mrs. Whitman’s shoulder,” Catherine said. “Clasping her hands to the wound, she shrieked with pain, and then fell to the floor. I ran to her and tried to raise her up.”

“Child, you cannot help me, save yourself,” Narcissa told Catherine.

Catherine helped carry her younger sisters and two other girls up to the attic, where they hid until dark. Several of the girls were sick with measles, and they called out desperately for water. Catherine could not help them. Finally they passed out from exhaustion. The attic grew quiet.

“I sat upon the side of the bed,” said Catherine, “watching hour after hour, while the horrors of the day passed and re-passed before my mind.” She heard the clock downstairs strike ten, then eleven, then midnight. She listened to the steady breathing of the sleeping children, and the sounds of cats’ paws on the floor downstairs.

Catherine and her sisters survived that terrible night. But Tiloukaikt and his men had killed the Whitmans and eleven other settlers, including two of Catherine’s brothers. Calling for vengeance, white settlers formed armed groups and attacked Cayuse villages, killing many people who had nothing to do with the crime. Tiloukaikt finally turned himself in. He and four other Cayuse men were tried for murder, found guilty, and hanged.

Between the measles epidemic and the attacks following the Whitman massacre, the Cayuse were nearly destroyed. Survivors went to live with other Native American groups.

And Catherine Sager was an orphan again. She and her sisters split up, moving in with different families in the Oregon Territory.

Violent clashes like those between the Cayuse and white settlers in Oregon didn’t happen every day, of course. But the Whitman massacre is an important story because it shows how tense things could get when large numbers of settlers started moving onto Native American lands. And it shows just how quickly those tensions could explode into violence.

Can you imagine what might happen if tens of thousands of settlers suddenly raced to the West? You’re about to find out.

By the start of 1848, a Swiss immigrant named John Sutter had built himself a nice little empire in central California. He owned nearly 50,000 acres, including farms, orchards, stores, even his own

fort—a walled complex of buildings called Sutter’s Fort (soon to become part of the new town of Sacramento).

In January 1848 Sutter hired a carpenter to build a sawmill on some of his land along the American River. The carpenter, James Marshall, led a small group of workers to the spot where Sutter wanted his mill. The men unloaded their tools and started working.

On the morning of January 24, Marshall was inspecting a freshly dug hole when he stopped suddenly. “My eye was caught with the glimpse of something shining in the bottom of the ditch,” he remembered. “I reached my hand down and picked it up. It made my heart thump.”

Marshall held in his palm a little yellow lump, dented and creased, about half the size of a pea. He collected a few more of these lumps and showed them to William Scott, one of the workers.

Marshall: I have found it!

Scott: What is it?

Marshall: Gold.

Scott: Oh! No, that can’t be.

Marshall: I know it to be nothing else.

Marshall was sure he had struck gold! Well, he was pretty sure. Actually, he didn’t really know. “It did not seem to be of the right color,” he later admitted.

James Marshall

Only one person on Marshall’s crew knew anything about gold mining—her name was Jennie Wimmer. As a teenager Wimmer had dug for gold in the streams of Georgia. Now she was working as a cook for Marshall’s men. All along she had been saying that the American River looked like a promising place to search for gold. No one listened.

Now Wimmer took one of Marshall’s nuggets and turned it over in her hands. It looked like yellow chewing gum, she thought, “just out of the mouth of a school girl.”

She looked up and said, “This is gold.”

To prove it, she dropped the nugget into a pot she was using to make lye (a chemical she needed to make soap). “I will throw it into my lye kettle …” she said, “and if it is gold, it will be gold when it comes out.”

Wimmer knew that lye (a strong base) would quickly tarnish most metals, but would have no effect on gold. The next morning she pulled the nugget out of her kettle. “And there was the gold piece as bright as could be,” she said.

The men were still not convinced.

Two days later, John Sutter was working in his office, listening to the rain pounding on his fort. He heard the door crash open and looked up. James Marshall was standing in the doorway.

“He was soaked to the skin and dripping water,” Sutter recalled. “He told me he had something of the utmost importance to tell me, that he wanted to speak to me in private.”

Even before that moment, Sutter had considered the excitable Marshall to be, as he put it, “like a crazy man.” Now Sutter must have been really worried. But he got up and shut the door.

“Are you alone?” Marshall asked.

“Yes,” said Sutter.

“Did you lock the door?”

“No, but I will if you wish it.”

Marshall wished it.

Then Marshall took a rag from his pocket and unwrapped it. Sutter stepped forward and saw a few little yellow blobs.

“Well, it looks like gold,” Sutter said. “Let us test it.”

He got down an encyclopedia, turned to the G section, and looked up gold. He performed the tests recommended in the book, including biting the metal—pure gold is so soft that you can bite down and leave a tooth mark in it.

“I declared this to be gold of the finest quality,” Sutter said.

He raced out to the American River and told his workers to keep the discovery secret. But as you’ve probably noticed, most people can’t keep secrets. The bigger the secret, the harder it is to keep. And this was a secret that was about to change the world.

Even after swearing his workers to secrecy, Sutter himself bragged to a friend: “I have made a discovery of a gold mine,

which, according to experiments we have made, is extraordinarily rich.”

Then, over the first few months of 1848, Sutter’s workers started showing up in San Francisco with bags of gold they had found. One worker went into a store and dropped a bag of gold flakes on the counter, announcing to everyone: “That there is gold, and I know it, and know where it comes from, and there’s plenty in the same place, certain and sure!”

Recognizing a good business opportunity when he saw one, a store owner named Sam Brannan paraded through San Francisco holding up samples of the gold found by Sutter’s workers and shouting, “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!”

As Brannan had hoped, people raced to his store to buy overpriced mining supplies. Then they rushed off to look for gold. By June 1848 three-quarters of San Francisco’s population was gone. Businesses and newspapers shut down. The only school in town closed its doors (and the teacher took his students along with him to search for gold).

“The whole population are going crazy,” one Californian said. “Old as well as young are daily falling victim to gold fever.”

A man named James Carson never forgot the moment he caught the fever. News of gold discoveries started reaching his town of Monterey, California, in the spring of 1848. He was sure the stories were exaggerated. Until …

“One day I saw a form, bent and filthy, approaching me,” Carson

remembered. “He was an old acquaintance and had been one of the first to visit the mines.”

This guy had once been neat and clean. Now his clothes were ripped and his wild hair and beard sprang out in all directions. Carson watched the man open a big bag filled with yellow chunks and flakes.

“This is only what I picked out with a knife,” the man told Carson.

As Carson gazed at the gold, he felt something strange happening inside him. “A frenzy seized my soul,” he said. Carson was catching a disease that was about to spread across the country, across the world.

“My legs performed some entirely new movements of polka steps … piles of gold rose up before me at every step; castles of marble, dazzling the eye … in short, I had a very violent attack of the Gold Fever.”

James Carson

One hour after dancing down the streets of Monterey, Carson had his mule packed with supplies and was hurrying to the gold mines.

Gold fever raced around the world, speeding through South America, Asia, Europe, even reaching the Australian island of Tasmania (eight thousand miles from California). A Tasmanian store owner started selling a new invention he called “gold grease.” The idea: you take off your clothes, smear your naked body with the stuff, roll down a hill—and the gold sticks to you.

American newspapers, meanwhile, were making it sound easy to get rich in California, even without magic grease. Readers in Philadelphia opened their papers and read a letter from a California miner: “Your streams have minnows and ours are paved with gold.” People all over the country were hearing similarly exciting stories.

“The gold excitement spread like wildfire, even out to our log cabin in the prairie,” remembered a Missouri settler named Luzena Stanley Wilson. “And as we had almost nothing to lose, and we might gain a fortune, we early caught the fever.”

Like so many Americans, the Wilson family packed up what they could carry, left everything else behind, and set out for California.

There was no good way to get to California. There were three bad ways.

First, you could cross the country by land, using oxen to drag your wagons along the trails to the western coast. This was bonebruising, slow, and dangerous—and getting more dangerous all the time. As the trails got busier, streams and wells along the way got more and more polluted with human waste. This led to the spread of cholera, an infection of the intestines that causes severe diarrhea and vomiting. Death was often miserable and quick, as a traveler named William Swain noted in his diary:

May 18: One of our company, Mr. Ives, is sick with cholera.

May 19: Mr. Ives is dead.

If you had about six hundred dollars to spare (which most people didn’t) you could travel by sea all the way around the southern tip South America and then north to California. This was safer than the overland trails, though you had to deal with storms, seasickness, rotting food, and barrels of drinking water that got so smelly, passengers had to add molasses and vinegar before they could bear to swallow it. For many, though, the real problem with this route was that it was 15,000 miles and took six months or more—too long to wait when you’ve got gold fever.

The quickest route (if everything went well) was to sail to Panama, cross the seventy-five-mile-wide strip of land by canoe and on foot, and then get in another ship bound for California. Shipping company advertisements made this sound like a pleasant little shortcut. The ads failed to mention that travelers would be tripping through tropical forests and dodging disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Nor did the ads mention that when you finally stumbled into Panama City, there would probably be no ship there to pick you up. Jenny Megquier and her husband were among thousands of travelers who got stuck on Panama’s Pacific coast. Every time a boat sailed

up, desperate crowds raced forward to try to get on. Megquier kept a positive attitude while waiting, though she did find some of the local bugs mildly annoying. “Another insect which is rather troublesome, gets into your feet and lays its eggs,” she wrote. The doctor and I have them in our toes—did not find it out until they had deposited their eggs in large quantities; the natives dug them out and put on the ashes of tobacco.”

Jenny Megquier eventually made it to California alive. So did William Swain and about 10,000 other hopeful people in 1848.

Getting there was just the start of the adventure. A young traveler named Leonard Kip realized this when his ship sailed into San Francisco’s harbor. Kip woke to the sounds of the ship’s captain barking curses. He found an officer and asked what was going on.

Kip: What’s the matter?

Officer: You will have to row yourselves ashore, as all the men have left.

Kip: Indeed!

Officer: Went off last night, on the sly, laughing at us on shore now—next week, in the mines.

This was happening a lot. As soon as ships arrived in San Francisco, entire crews raced to shore and headed inland to join the gold rush. Kip looked around and saw the result: hundreds of ships gently rocking in the harbor. They were flying flags from all over the world. They were all empty.

Kip got the feeling he was entering a very strange new world.