In the early 1870s factories in the East started using buffalo hides to make leather for shoes, belts, and bags. The word spread west—hunters could make a fortune by bringing in buffalo hides. “They were walking gold pieces,” Frank Meyer said of the buffalo. “I was young, twenty-two. I could shoot. I liked to hunt. I needed adventure. Here was it. Wouldn’t you have done the same thing if you had been in my place?”

There had been about thirty million buffalo in the West when white settlers started arriving. Now buffalo hunters started killing more than a million of them every year. They sometimes blasted buffalo so quickly that their rifles overheated and they had to urinate down the barrels to cool them off. After killing the animals, hunters stripped off the hides, leaving the bodies to rot in the sun.

Some hunters didn’t even bother to take the hides. A woman named Elizabeth Custer got a close-up view of the buffalo slaughter while heading west by train to meet her husband, an officer in the army. “I have been on a train when the black, moving mass of buffaloes before us looked as if it stretched on down to the horizon,” Custer said. As soon as passengers (the men, that is) spotted the herds, they yanked guns from their suitcases and stuck them out the windows of the moving train.

“It was the greatest wonder that more people were not killed,” she said, “as the wild rush for the windows, and the reckless discharge of rifles and pistols, put every passenger’s life in jeopardy.”

The men considered this great fun (and like Custer said, only a few passengers got shot). To the Plains Indians, it was cruel and crazy.

“Everything the Kiowa had came from the buffalo,” said one Kiowa woman. “Their tepees were made of buffalo hides, so were their clothes and moccasins. They ate buffalo meat. Their containers were made of hide, or of bladders or stomachs. The buffalo were the life of the Kiowa.” The buffalo were just as important to the Cheyenne, Lakota, and other Plains Indians.

This actually explains why the U.S. government supported the work of buffalo hunters. Once there were no more buffalo to hunt, Plains Indians would no longer be able to roam freely across the plains. Unable to live their traditional way of life, they’d be forced to settle down on reservations.

As General William T. Sherman saw it, killing buffalo was a way of defeating the Plains Indians—and it was a lot easier (also cheaper and safer) than fighting the Indians directly. “Let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo is exterminated,” Sherman said of buffalo hunters. “It is the only way to bring peace and allow civilization to advance.”

It was a harsh strategy. And it was working. “The great buffalo slaughter commenced in the West,” remembered the cowboy Nat Love. “And in 1877 they had become so scarce that it was a rare occasion when you came across a herd containing more than fifty animals, where before you could find thousands in a herd.”

With the buffalo herds disappearing, more Plains Indians groups agreed to move onto reservations. But the Lakota chief Sitting Bull refused to even consider such a move.

As a young boy he had been known by the name Hunkesni, which means “slow.” It wasn’t an insult, exactly. It’s just that he had a serious stubborn streak, doing everything at his own pace. By 1874, Sitting Bull was a respected chief in his early forties. He was still stubborn too: stubbornly convinced that his people had the right to continue to live free on their own land. As he said to Indians who had agreed to settle on reservations and live on food from the American government:

“The whites may get me at last, as you say, but I will have good times till then. You are fools to make yourselves slaves to a piece of fat bacon, some hard-tack, and a little sugar and coffee.”

Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull was confident the Lakota could continue living in their traditional way—thanks to

the huge Great Sioux Reservation, the territory won by the Lakota in Red Cloud’s War. The Black Hills, in what is now South Dakota, were an especially rich hunting region of the Great Sioux Reservation. According the Fort Laramie Treaty between the Lakota and the U.S. government, this land belonged to the Lakota forever.

So what was the American army doing there? That’s what Lakota leaders were wondering in the summer of 1874 (just eight years after the treaty was signed) as they watched an army officer named George Armstrong Custer lead one thousand American soldiers into the Black Hills. The Lakota knew Custer well—he was famous for his flowing blond hair and his aggressive battle style. Once, after chasing a group of warriors for hours without ever getting out of his saddle, the Lakota nicknamed him “Hard Backsides.”

Custer claimed he was in the Black Hills just looking things over, making sure the Lakota were behaving themselves (not that he had any legal right to do that). The truth is, rumors were swirling about gold in those hills. Custer was ordered to go have a look.

“Our people knew there was yellow metal in little chunks up there,” said a Lakota

teenager named Black Elk. “But they did not bother with it, because it was not good for anything.”

Custer did not agree. “We have discovered a rich and beautiful country,” he wrote to his wife, Elizabeth (without explaining how you can “discover” a country where other people are already living). He was thrilled by the opportunity to add to his growing collection of western wildlife: “I have one live rattlesnake,” he told Elizabeth, “two jack-rabbits, half-grown, one eagle, and four owls. I had also two fine badgers, full-grown, but they were accidentally smothered.”

More important, Custer’s soldiers squatted in streams to pan for gold. It was there, all right. “We have discovered gold without a doubt, and probably other valuable metals,” he reported.

Sitting Bull watched Custer’s army march out of the Black Hills and back toward American territory. There would be no fighting that summer. The Lakota just watched and waited and wondered what the Americans were really up to.

They found out soon enough. Custer’s discovery was headline news all over the country. “Rich Mines of Gold and Silver Reported Found by Custer,” announced one newspaper. This set off a new gold rush, with thousands of miners swarming into the Black Hills.

The American army was legally required to remove the miners. But the government decided it would be simpler just to buy the Black Hills. “You should bow to the wishes of the government,” one senator told Lakota leaders. “Gold is useless to you, and there will be fighting unless you give it up.”

When Sitting Bull heard the government was setting up a conference to work out a price for the Black Hills, he sent a message to President Grant. “I want you to go and tell the Great Father that I do not want to sell any land to the government,” he told an interpreter. Picking up a pinch of dust, he added: “Not even as much as this.”

The government officials came west anyway and tried negotiating with the few chiefs who were willing to talk. It did not go well. The government offered six million dollars for the Black Hills. Far too low a price, the chiefs responded. While the arguments flew back and forth, three hundred Lakota warriors rode up to the outdoor meeting. Holding rifles high in the air, they sang a new song specially written for the occasion:

The Black Hills is my land and I love it

And whoever interferes

Will hear this gun.

And whoever interferes

Will hear this gun.

The frustrated (and nervous) government men hurried back to Washington, D.C., to report their failure. At this point, President Grant and General Sherman decided they were done negotiating. They sent a warning to Sitting Bull and the other Lakota leaders: Report to reservations by January 31, 1876—or the army will come and bring you in.

The job of actually going and getting the Lakota fell to American soldiers stationed in western forts. Here was yet another very tough way to make a living in the West.

Low-paid soldiers spent years stuck in small log forts, hundreds of miles from anywhere. The loneliness and boredom were unbearable. So was the food, which included case after case of moldy biscuits left over from the Civil War.

There were unexpected troubles too, as Martha Summerhayes discovered. Martha’s husband, Jack, an army lieutenant, was assigned to a fort in the West. Like many officers’ wives, she decided to go with him.

“Our sleeping room was very small,” she said, “and its one window looked out over the boundless prairie at the back of the post.” Summer nights were baking hot, and they had to sleep with their window wide open. Along with a slight breeze, this let in the growls of mountain lions. Nothing to worry about, her husband assured her.

One night the cat cries seemed a little closer. “I asked him if they ever came in,” Martha remembered.

“Gracious, no!” Jack said. “They are too wild.”

So she tried again to get comfortable in bed.

“I calmed myself for sleep—when like lightning, one of the huge creatures gave a flying leap in at our window, across the bed, and through into the living-room.”

“Jerusalem!” shouted Lieutenant Summerhayes.

He tumbled out of bed, grabbed his sword from the corner, and, swinging and stabbing wildly, chased the wild cat back into the bedroom, onto the bed, over Martha, and out the open window.

Nothing this exciting (or dangerous) usually happened in western forts. The two biggest health hazards in the forts were disease and alcohol abuse. Soldiers were often so bored that they welcomed the chance to march off toward battle.

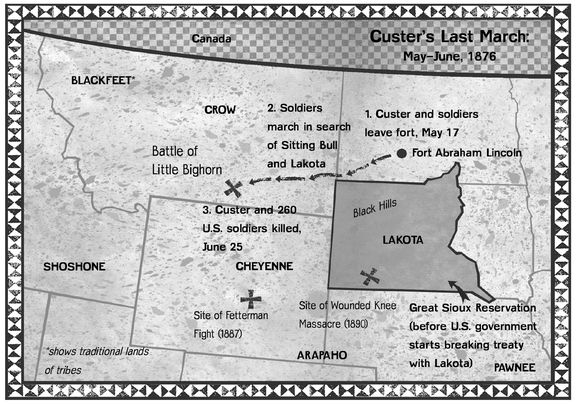

That’s exactly what happened in May 1876. The government’s deadline had come and gone. Sitting Bull and most of the Lakota still refused to surrender. “I think we will have some hard times this summer,” a soldier named T. P. Eagan wrote to his sister. “The old chief Sitting Bull says that he will not make peace with the whites as long as he has a man to fight.”

T. P. Eagan and the rest of George Armstrong Custer’s Seventh Cavalry rode away from Fort Abraham Lincoln, off to find Sitting Bull and drive him onto a reservation. Everyone knew it would be a risky job. “The wives and children of the soldiers lined the road,” Elizabeth Custer remembered. “Mothers, with streaming eyes, held their little ones out at arm’s length for one last look at the departing father.”

Then the soldiers marched away. All the families could do was stay in the fort and wait for news.

“We have not seen any signs of Indians thus far,” Custer wrote to his wife on May 20. He added that he and his brother, an officer in his unit, were having a wonderful time. “Tom and I have fried onions at breakfast and dinner,” he wrote, “and raw onions for lunch!”

“They both took advantage of their first absence from home to partake of their favorite vegetable,” Elizabeth noted. “Onions were permitted at our table, but after indulging in them they found themselves severely let alone, and that they did not enjoy.”

Custer sent an update on June 21: his scouts had found a fresh trail left by a large group of Indians. “I feel hopeful of accomplishing great results,” he wrote.

“I have but a few moments to write,” he added the next day. “We move at twelve, and I have my hands full of preparations … . Do not be anxious about me … . I hope to have a good report to send you by the next mail.”

Two days later Custer stood on a hilltop looking through binoculars toward a huge Indian camp along the banks of the winding Little Bighorn River.

“The largest Indian camp on the North American continent is ahead and I am going to attack it.”

George Armstrong Custer

Determined to surprise his enemy, Custer decided to attack without taking time to study the geography or find out how many warriors he might be facing. He divided his forces, leading 210 men toward the camp himself. Another force, led by Major Marcus Reno, approached the camp from a different direction.

“We’ll find enough Sioux to keep us fighting two or three days,” predicted a Crow Indian who was working as a scout for Custer.

Custer shook his head. “I guess we’ll get through them in one day,” he said.

“It was somewhere past the middle of the afternoon, and all of us were having a good time,” remembered a Cheyenne woman of the moment before Custer’s attack on June 25, 1876.

More than six thousand Lakota, Cheyenne, and other Indian allies—including about two thousand warriors—were camped along the Little Bighorn. They knew the Americans were out there somewhere. “I was thirteen years old and not very big for my age,” remembered Black Elk, “but I thought I should have to be a man anyway.” He was swimming with friends in the Little Bighorn when he heard sudden shouts:

“The chargers are coming!”

“They are charging!”

Black Elk ran to his family’s lodge for his rifle. His friend Iron Hawk, who was fourteen, also prepared for battle. “I was so shaky that it took me a long time to braid an eagle feather into my hair,” he said.

Nearby, young warriors ran into Sitting Bull’s lodge, shouting that Custer was attacking. “I jumped up and stepped out,” said Sitting Bull. He saw waves of blue-coated American soldiers blasting away as they charged on horses into camp. “The bullets were like humming bees,” he said. “We thought we were whipped.”

“They came on us like a thunderbolt,” said a Lakota chief named Low Dog. “I never before nor since saw men so brave and fearless as those white warriors.”

Crazy Horse helped rally the Indian forces, shouting: “It is a good day to fight! It is a good day to die! Strong hearts, brave hearts, to the front! Weak hearts and cowards to the rear!”

“Then came the rush of the enemy,” said Billy Jackson, an American soldier who was part of Major Reno’s charge. Jackson and the

other soldiers suddenly saw at least five hundred Indian warriors charging toward them. “Their shots, their war cries, the thunder of their horses’ feet were deafening,” Jackson said.

Somewhere in the middle of this chaos, Custer was waving his hat and shouting, “Courage, boys, we’ve got them!” But now that Custer was in the Indian camp, he must have realized how badly outnumbered his soldiers were. It was too late to do anything but try to fight his way out.

Witnesses described the next few minutes as a confusing mix of swirling dust, gunshots, and shouts of pain and fury. Custer’s soldiers split into smaller groups, but they were all quickly surrounded. “I think they were so scared that they didn’t know what they were doing,” Black Elk said. “The shooting was quick, quick, pop—pop—pop, very fast,” said a warrior named Two Moons. “We circled all around them—swirling like water round a stone.”

With no time to reload, men swung their guns at each other like clubs. They wrestled and punched and bit. Many of Custer’s soldiers finally threw down their weapons. They were ready to surrender.

But the Indians kept on attacking. Sitting Bull’s cousin watched Indian warriors shooting and stabbing Custer’s men after they tried to surrender. “The blood of the people was hot and their hearts bad,” she said, “and they took no prisoners that day.”

Major Reno and his surviving soldiers—who had attacked from the other side of the Indian camp—never saw what happened to Custer. They spent an endless night on a nearby hill, wondering why they received no messages or orders from Custer. “We felt terribly alone on that dangerous hilltop,” said a soldier named Charles Windolph. “We were a million miles from nowhere. And death was all around us.”

When Reno’s men finally made it to safety, they found out why they hadn’t heard from Custer. “We had a closer view of Custer’s battlefield,” one of the soldiers said. “We saw a large number of objects that looked like white boulders scattered over the field.”

As they walked nearer, they realized that these were not boulders. They were the bodies of Custer’s soldiers, stripped and badly cut up. The men wept as they walked among the bodies, looking for friends.

Meanwhile, back at Fort Abraham Lincoln, the soldiers’ families were suffering through the hot summer of 1876, waiting for news. “Our little group of saddened women, borne down with one common weight of anxiety, sought solace in gathering together in our house,” said Elizabeth Custer.

One day, while the women were singing to pass the time, a messenger arrived. It was an Indian named Horn Toad, one of Custer’s scouts. Panting from exhaustion, he delivered the news in short sentences: “Custer killed. Whole command killed.”

Horn Toad’s report was accurate. Custer and every one of the 210 men he led into battle were dead. Another fifty men from Major Reno’s force had been killed. It was by far the biggest defeat the American military ever suffered in the Indian wars.

The news from Little Bighorn shocked the entire nation—coming right at the moment Americans were celebrating the country’s one hundredth birthday. General William T. Sherman promised to send more soldiers west to crush the Lakota once and for all.

Back at Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull and the other chiefs realized they had won a historic victory. They also knew Sherman. They knew he would come after them harder than ever now, and they were not really prepared. The recent fighting had left them nearly out of ammunition.

The huge Indian camp on the Little Bighorn split up, with smaller groups marching off in different directions.

Sherman’s forces went on the attack right away, just as the harsh northern plains winter began. “The worse it gets, the better,” said General George Crook, who led the attacks. “Always hunt Indians in bad weather.”

Crook pushed his shivering soldiers on long marches across the frozen plains. “I know it looks hard, but we’ve got to do it, and it shall be done,” he said. “If necessary we can eat our horses.”

“I’d as soon think of eating my brother,” grumbled a young officer (not loud enough for the general to hear).

All winter Crook’s soldiers surprised Lakota and Cheyenne villages, capturing horses and destroying food supplies. Indians who survived the attacks were scattered in the snow without food or tents. After attacking one village, an American soldier reported: “The thermometer never got higher than 25 below … . Those poor Cheyenne were out there in that weather with nothing to eat, no shelter.”

Sitting Bull led about one thousand people across the border into Canada, where they were safe from American attacks. But for those unable to escape, there was little chance of finding food on the plains. Buffalo were getting scarce now. As the winter

dragged on, groups of Indians started coming in to reservations. “I am tired of being always on the watch for troops,” explained Red Horse, a Lakota chief. “My desire is to get my family where they can sleep without being continually in the expectation of an attack.”

The Lakota teenager Black Elk felt the same way. “Wherever we went, the soldiers came to kill us,” he said of that winter. He and his family went in to a reservation. There, in May 1877, he watched the surrender of a leader he had grown up idolizing. “Crazy Horse came in with the rest of our people,” said Black Elk, “and the ponies that were only skin and bones.”

American soldiers took the famous warrior’s weapon They handed him some beef and beans.

“I want this peace to last forever,” Crazy Horse said.

General Crook wanted peace too. But he had his own ideas about how to keep it—he wanted Crazy Horse locked up.

Crazy Horse

A group of soldiers surrounded Crazy Horse. They reached for his arms.

“Don’t touch me!” he yelled.

The soldiers started dragging him across the reservation. When he saw he was being taken toward a tiny jail cell, Crazy Horse yanked free and pulled out a knife.

“Kill him! Kill him!” soldiers shouted.

A soldier lunged forward and stabbed Crazy Horse with his bayonet. A few other soldiers reached for the fallen warrior.

“Let me go, my friends,” Crazy Horse said. “You have got me hurt enough.” Crazy Horse died that night. “I cried all night, and so did my father,” Black Elk said.

From his homeland in Oregon, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce watched the fall of the powerful Plains Indians. The message was clear: Indians could win battles against American soldiers. But even the most powerful groups could not win wars against the United States.

Joseph was determined to help the Nez Perce hold on to their traditional territory in Oregon’s Wallowa Valley. He had sworn to his dying father that he would never give up this land.

“You must stop your ears whenever you are asked to sign a treaty selling your home,” Joseph’s father told him. “My son, never forget my dying words. This country holds your father’s body. Never sell the bones of your father and mother.”

“I pressed my father’s hand and told him I would protect his grave with my life,” Joseph said.

This promise put Joseph in an impossible position in 1877. Actually, it wasn’t the promise that caused trouble—it was that American settlers were moving onto Nez Perce land.

How was Joseph supposed to defend this land once the United States decided to take it?