THE ISLAMIC VIEW OF THE QURAN

Muhammad Mustafa al-Azami

According to the traditional Islamic understanding of the revelation of the Quran, Muhammad was a monotheist (ḥanīf) even before being chosen as a prophet. He believed in the One God of Whom the prophet Abraham had spoken before him and, like his ancestor, Muhammad never worshipped idols. He was also a contemplative who would withdraw from time to time to a cave called al-Ḥirāʾ on Jabal al-Nūr (“Mountain of Light”), a hill near Makkah, to meditate and be alone with God. On one of these occasions, when Muhammad was forty years old, the Archangel Gabriel (Jabraʾīl or Jibrīl) appeared to him and commanded him to recite (or read), to which Muhammad responded that he could not do so as he was unlettered (ummī). But the Archangel insisted, and the Prophet repeated his response. This exchange continued until Gabriel revealed to him the very first verses of the Quran:

Recite in the Name of thy Lord Who created, created man from a blood clot. Recite! Thy Lord is most noble, Who taught by the Pen, taught man that which he knew not. (96:1–5)

These verses mark the first descent (tanzīl) or revelation (waḥy) to the Prophet. During the next twenty-three years, until shortly before his death, the Quran was continuously revealed to him bit by bit, often in response to existent circumstances and conditions. According to one of the most important transmitters of Prophetic traditions, or Ḥadīth, Ibn ʿAbbās ibn ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib (d. 68/687), the entire Quran was made to descend by God in one night to the lowest Heaven and then revealed on earth in stages that He determined.1

The Revelation

Certain events can be described to, but not fully comprehended by, those who have had no experience of them, such as describing colors to a blind person. Similarly, the advent of revelation and its reception by a prophet are outside the realm of the ordinary experience of human beings. To understand this phenomenon we have to have faith and depend solely on authentic reports from the Prophet and those trustworthy individuals who witnessed him. These include:

Once the Prophet was asked, “O Messenger of God, how does the revelation come to thee?” He replied, “Sometimes it comes like the ringing of a bell, and that is the hardest on me; then it leaves me, and I retain what it said. And sometimes the angel approaches me in human form and speaks to me, and I retain what he said.”2

ʿĀʾishah related, “Verily, once before leaving him I saw the Prophet when the revelation descended upon him on a day that was severely cold. And behold, his brow was streaming with sweat.”3

Yaʿlā once told ʿUmar of his desire to observe the Prophet while he was receiving revelation (waḥy). At the next opportunity ʿUmar called out to him, and he witnessed the Prophet “with his face red, breathing with a snore. Then the Prophet appeared relieved [of that burden].”4

Zayd stated, “Ibn Umm Maktūm came to the Prophet while he was dictating to me the verse, Those who stay behind among the believers . . . and those who strive in the way of God with their goods and lives are not equal (4:95). On hearing the verse, Ibn Umm Maktūm said, “O Prophet of God, had I the means I would most certainly have participated in jihād.” He was a blind man, but added, “So God revealed except for the disadvantaged to the Prophet while his thigh was on mine, and it became so heavy that I feared my thigh would break.”5

The Prophet never possessed any control over when or where the revelation would take place or what it would say. This is evident from numerous incidents. Once some people slandered his wife ʿĀʾishah, accusing her of adultery. The Prophet received no immediate revelation, and in fact he suffered for a full month before God declared her to be innocent in 24:16.

THE PROPHET’S ROLES WITH REGARD TO THE QURAN

The Quran mentions in many places that the Prophet will recite (from the root t-l-w) the revelation to the people (2:129, 151; 3:164; 22:30; 29:45), alluding to his role in disseminating the revelation throughout the community. However, recitation is accompanied by teaching, which was part of Abraham’s supplication to God interpreted by Muslims to refer to the coming of the Prophet Muhammad:

Our Lord, raise up in their midst a messenger from among them, who will recite Thy signs to them, and will teach them the Book and Wisdom, and purify them. (2:129)

The Prophet’s duties toward the revelation (waḥy) he received were many. Not only was he the instrument for the reception of the Divine message; he was also to supervise the proper compilation of the revealed verses, provide the necessary explanations, encourage community-wide dissemination of the revelation, and teach his Companions in light of Quranic injunctions. Just like the message itself, the order of the compilation of the verses and the content of each sūrah came from God, not from the Prophet or scribes, and it was his duty to see them faithfully represented. And so after he memorized what was revealed to him, the recitation of the verses to the Companions, the compilation of the verses, the explanation of the meaning of the verses, and the education of the early Muslims became the Prophet’s prime objectives throughout his prophethood, duties he discharged with tremendous resolve, sanctioned, guided, and protected in his efforts by God. As for explanation of the revelation, the literature of the Prophet’s Sunnah (or the Ḥadīth) as a whole constitutes his elucidation of the Quran and his incorporation of its teachings into practical everyday life.6 The Ḥadīth and Sunnah of the Prophet constitute in fact the first commentary on the Quran.

To continually refresh the Prophet’s memory, the Archangel Gabriel would visit him specifically for that purpose on many occasions every year. To quote some aḥādīth and reports of some of the Companions:

The Prophet’s daughter Fāṭimah said, “The Prophet informed me secretly, ‘Gabriel used to recite the Quran to me and I to him once a year, but this year he has recited the entire Quran with me twice. I do not think but that my death is approaching.’”7

Ibn ʿAbbās reported that the Prophet would meet with Gabriel every night during the month of Ramadan, till the end of the month, each reciting [the Quran] to the other.8

Abū Hurayrah said that the Prophet and Gabriel would recite the Quran to each other once every year, during Ramadan, but that in the year of his death they recited it twice.9

TEACHING THE QURAN

There are no indications that the Prophet ever learned to write, and it is generally believed that he remained unlettered throughout his life. He nevertheless maintained the importance of the skill of writing, whose instruction, in one ḥadīth, is described as the duty of a father toward his son.10 He ordered the literate and the illiterate to cooperate with one another in teaching the Quran and spared no effort in encouraging the community to learn the Word of God. The following reports confirm this fact:

ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān reports that the Prophet said, “The best among you is the one who learns the Quran and teaches it.”11

According to Ibn Masʿūd, the Prophet remarked, “If anyone recites a letter from the Book of God, then he will be credited with a good deed, and a good deed attains a tenfold reward. I do not say that alif lām mīm are one letter, but that alif is a letter, lām is a letter, and mīm is a letter.”12

Among the immediate rewards for learning the Quran was the privilege of leading fellow Muslims in prayer as an imam, a crucial function, especially in the early days of Islam.13

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb states that the Prophet said, “With this Book God exalts some people and lowers others.”14

ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAmr reports these words from the Prophet: “The one who was devoted to the Quran will be told [on the Day of Judgment] to recite and ascend, and to recite with the same care he practiced while he was in this world, for he will reach his abode [in Heaven] with the last verse he recites.”15

Most of the Quran was revealed in Makkah, and ʿAlī, Ibn Masʿūd,16 Khabbāb,17 and other notables from among the Prophet’s Companions were already engaged in teaching the Quran during this period. After the migration to Madinah, many more joined their ranks as teachers, and some were even dispatched for that purpose outside Madinah, for example, Muʾādh ibn Jabal, who was sent to Yemen, and Abū ʿUbaydah, who was sent to Najrān.18

Collection and Recording of the Quran

We have evidence that verses were recorded even during the hardships the Muslims suffered at the hands of the Quraysh. The following famous incident illustrates this point. ʿUmar, prior to his conversion to Islam, drew his sword intending to cause harm at a gathering of the Prophet and about forty followers. One of the Companions tried to dissuade ʿUmar by telling him that his own sister and her husband had followed Muhammad in his new religion. Hearing this news, ʿUmar headed to his brother-in-law’s house, where Khabbāb was reciting the sūrah Ṭā Hā from a parchment. When ʿUmar’s sister heard his voice, she hid the parchment between her thighs, but, when discovered, she refused to let ʿUmar so much as touch the parchment until he had cleansed himself.19 This narration reveals that verses were kept in written form even during this early period. As for ʿUmar, his angry quest that day ended in his embracing Islam.

According to Ibn ʿAbbās, verses revealed in Makkah were recorded in Makkah.20 During the Madinan period, approximately sixty-five Companions functioned as scribes for the Prophet at one time or another.21 Upon the descent of revelation, the Prophet would regularly call for one of his scribes to write down the latest revealed verses.22 Often this was Zayd ibn Thābit, whose proximity to the Prophet’s Mosque granted him this most golden of opportunities.23 Shiite sources insist that ʿAlī also often carried out this task. There is also evidence of proofreading after dictation; once the verses were recorded, the scribe would read them back to the Prophet to ensure that no scribal errors had crept in.24 Given the large number of scribes and the Prophet’s custom of having new verses recorded, we can assume that the entire Quran was available in written form during the Prophet’s lifetime, a fact corroborated in numerous traditional sources.

ORDER OF THE VERSES

If an editor were to change someone else’s book, say, by rearranging the words or changing the sequence of the sentences, it would be very easy to shift the entire meaning of the work. We can in fact no longer attribute this new product to the original author, as only the author is entitled to change the material if the rightful claim of authorship is to be preserved. So it is with the Book of God, for He is the sole Author and He alone can arrange the material within His book. We read:

Surely it is for Us to gather it and to recite it. So when We recite it, follow its recitation. Then surely it is for Us to explain it. (75:17–19)

According to Muslim belief, God Himself sanctioned the Prophet’s arrangement of the verses and their explanation, making them authoritative. Only the Prophet, through Divine Guidance, was qualified to arrange the verses in the order in which they appear in the Quran that we now possess. Whenever revelation occurred, the Prophet asked his scribe to place the new verses in a particular position,25 and no Muslim from any part of the Islamic world has subsequently claimed the right to organize the Book of God in any other way.

We have a wealth of evidence indicating that the verses in the sūrahs have always existed in the arrangements that are to be found in the manuscripts of the Quran that we have. ʿUthmān ibn Abi’l-ʿĀṣ reports that he was sitting with the Prophet when the latter fixed his gaze upon a definite point and then said that the Archangel Gabriel had expressly asked him to place 16:90 in that particular position within that particular sūrah.26 A similar narration exists for 2:281, according to many the last verse revealed to the Prophet.27 But the clearest evidence of all is the history of the recitation of the sūrahs during the five daily prayers. A public recital of verses in unison cannot occur if the sequence of verses is in dispute, and no incident indicating such a problem is known to have taken place.

Although the order of the verses is the same for Sunnis and Shiites and both groups maintain that the order was determined through Divine Guidance and not by later generations, the numbering differs. In the copies of the Quran found in the Sunni world, the basmalah, that is, In the Name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful, is not counted as the first verse except for the first sūrah, al-Fātiḥah. It is the verse after the basmalah that is considered the first verse of most of the remaining sūrahs. In the copies of the Quran commonly found in the Shiite world, the basmalah is counted as the first verse and therefore each following verse is one number higher than that same verse in Sunni copies. (Sūrah 9, al-Tawbah, does not begin with the basmalah, so enumeration of the verses of that sūrah is the same for both segments of the Islamic community.)

Finally, the few variant readings of certain words are found in both Sunni and Shiite copies of the Quran and cannot be used as factors to distinguish the actual text of the Quran accepted by Sunnis from that accepted by Shiites. Except for the inclusion or exclusion of the basmalah in the enumeration of the verses, there is no difference at all between the text of the Quran accepted as the verbatim revelation of the Word of God by Sunnis and Shiites alike.28

ORDER OF THE SŪRAHS

The unique format of the Quran allows each sūrah to function as an autonomous unit. There are no chronologies or narratives that span multiple sūrahs, although there are a few cases, such as Sūrahs 8 and 9, where the ideas expressed continue from one sūrah to the next. Each sūrah stands as an independent unit even if the meaning of this or that verse in a particular sūrah is clarified in another sūrah with similar verses. This fact is the basis for commenting on the Quran through the text of the Quran, a method used in some well-known commentaries.

Because of their independence, it is possible and permissible to change the order of the sūrahs for recitation or study. Scholars agree unanimously, however, that it is not necessary to follow the sūrah order in the Quran in prayer, recitation, teaching, or memorization.29 The Prophet himself once recited Sūrahs 2, 4, and 3 (in that order) in a single rakʿah, or prayer cycle.30 The same is true regarding partial muṣḥafs, or “copies.” It is permissible to copy selected sūrahs in whatever order one chooses, akin to the traveler who prefers to take along a few photocopied pages rather than hauling a whole guidebook in the suitcase. There are many examples of partial muṣḥafs. In the Salar Jung Museum, in Hyderabad, India, an eleventh/seventeenth-century manuscript has the following order of sūrahs: 36, 48, 55, 56, 62, 67, 75, 76, 78, 93, 94, 72, 97, and 99–114. Another from the late thirteenth/nineteenth century has the order 36, 48, 78, 56, 67, 55, and 73.31

Nevertheless, the possibility of studying, reciting, or memorizing the sūrahs of the Quran in the order one wishes does not mean that the actual existing order of the 114 sūrahs is based on humanly contrived convention or that the written order can be changed. It is universally accepted by traditional Muslim scholars that, just as Gabriel directed the Prophet to place a particular verse or set of verses in a particular sūrah, the Archangel also instructed the Prophet in the ordering of the sūrahs. Muslims hold that, although the whole of the written Quran was not bound in a single volume during the lifetime of the Prophet, the order followed in the ʿUthmānī Muṣḥaf and later copies of the Quran is based on the instructions of the Prophet himself. It is he who ordered al-Fātiḥah to be placed at the beginning of the Quran, followed by al-Baqarah, the longest sūrah of the Quran, then Āl ʿImrān, and so on.

The ordering of the sūrahs is not chronological; that is, it is not based on the date of the descent of a sūrah, so that those revealed earlier come before those revealed later. But the order of the sūrahs is not accidental or without its own inner logic either. After al-Fātiḥah, longer sūrahs usually precede shorter ones, although this general quantitative rule is not absolute. In any case the ordering of the sūrahs is part of the Divinely ordained structure of the Quran.32

Compilation of the Quran

It can therefore be asserted categorically that, although the Prophet pursued all possible measures to preserve the Quran, he did not have all the sūrahs bound into a single master volume during his lifetime; he had, however, given instructions about their order. Zayd ibn Thābit stated, “The Prophet was taken [from this life] and the Quran had not yet been collected into a [bound] book.”33

COMPILATION DURING ABŪ BAKR’S ERA

Following the Prophet’s death in 11/632, Abū Bakr was chosen by the majority of Companions as the leader of the burgeoning Muslim community. Upon the Prophet’s passing, incidents of separatism flared up here and there. Chief among them was the claim of Musaylimah the Liar, whose stronghold was in the Yamāmah region in central Arabia and whose forces exceeded forty thousand. When the Muslim army marched against them in battle, the Muslims were victorious, but suffered heavy losses. Many Companions were martyred, and yet Musaylimah was only one of eleven leaders who had openly proclaimed some form of opposition. ʿUmar feared that with Yamāmah and all other ongoing theaters of war, the community of the ḥuffāẓ (those who had memorized the Quran by heart) would soon be wiped out.34 He therefore counseled the Caliph, Abū Bakr, to take the initiative and begin collecting the text of the Quran.

Once he became of the same mind as ʿUmar, Abū Bakr entrusted this momentous task to Zayd ibn Thābit, to whom he remarked, “You are young and intelligent. You used to record the revelations for the Prophet, and we know of nothing that would discredit you.”35 And with this pronouncement, Abū Bakr put his seal of approval upon Zayd’s qualifications: he was young (in his early twenties) and therefore full of vitality and energy, literate, and intelligent (i.e., he possessed the necessary competence for the task), and he had prior experience in recording the revelations. In addition, Zayd had been one of the fortunate few to attend the Archangel Gabriel’s recitations of the Quran with the Prophet during the month of Ramadan.

Abū Bakr’s Instructions to Zayd

The Quranic injunction to write down the terms of business transactions and have them witnessed by two people (2:282) became the basis for the method followed by Zayd. Abū Bakr instructed Zayd to sit at the entrance to the mosque in Madinah and to record only those verses of the Quran brought to him that were validated by two witnesses. Very soon the project blossomed into a true community effort. Though the focus was on primary written sources recorded on parchment, animal skin and bones, wooden planks, and such, the writings were not only verified against each other, but also against the memories of those who had learned the verses directly from the Prophet. Zayd applied the same stringent conditions for acceptance whether the source was written or based on human memory, and in either case he always insisted on two witnesses.36 In any case human memory was only used to reinforce the written word, not to substitute for it. According to the Ḥadīth scholar Ibn Ḥajar (d. 852/1448), Abū Bakr had authorized Zayd to record only what was available in written form. That is why Zayd abstained from including the last two verses of Sūrah 9 until he came upon them in written form even though he and his fellow Companions could recall them perfectly well from memory.37

This procedure shows that nothing was taken for granted, not even Zayd’s own recording and memorization of the revealed verses, and that everything required corroboration. Once complete, the compiled Quran, called the Ṣuḥuf, was saved in the “state archives” under the Caliph’s custodianship.38 On his deathbed Abū Bakr entrusted this text to his successor, ʿUmar, whose reign witnessed the blossoming of schools for the memorization of the Quran in Arabia as well as in the Fertile Crescent area. Toward the end of 23/644 Caliph ʿUmar was fatally stabbed by a slave, but, before passing away, he handed over the Ṣuḥuf to his daughter Ḥafṣah, who was a widow of the Prophet.

Zayd’s Methodology in Compiling the Quran

The typical procedure in collating manuscripts is to compare different copies of the same work. Of course not all copies are equal. In modern times the German orientalist Gotthelf Bergsträsser set out a few important rules39 for this kind of scholarship:

1. Older copes are usually more reliable than newer ones.

2. Copies that were revised and corrected by the scribe through comparison with the mother manuscript are superior to those that lack this step.

3. If the original is extant, any copy made from it has no significance.40

For those who consider modern methods of scholarship sacrosanct, it is of some interest to note that the same benchmarks set by leading fourteenth/twentieth-century orientalists were applied by Zayd fourteen centuries ago in compiling the Quran. The Prophet’s time in Madinah had been one of intense scribal activity, and many Companions possessed verses that were copied from the parchments, wooden planks, and other materials of friends and relatives.41 Zayd, however, limited himself to those writings that were transcribed under the Prophet’s supervision (rule 3), thereby guaranteeing the greatest possible accuracy. Zayd had memorized the Quran and inscribed much of it while seated before the Prophet; his memory and writings could only be compared with material of the same status, not with second- or thirdhand reports and copies.

COMPILATION DURING ʿUTHMĀN’S ERA

During the reign of ʿUthmān (24–36/644–56), the third Caliph, Muslims were engaged in battles in the expanses of Azerbaijan and Armenia in the north. The fighting forces hailed from various tribes and provinces, each with its own dialect, and the resulting regional differences over the pronunciation of the Quran caused some friction within the ranks. Eyeing these tensions firsthand, Ḥudhayfah ibn al-Yamān warned ʿUthmān, “O Caliph, take this ummah (community) in hand before they differ about their Book like the Christians and Jews.”42 In an assembly ʿUthmān sought the people’s advice, and when asked for his own view, his solution was simple and clear: “I see that we should provide the people with a single muṣḥaf, so that there is neither division nor discord.” All those in the assembly applauded his idea.43

There are two accounts of the way ʿUthmān proceeded with this task. According to the first version, ʿUthmān made copies based exclusively on the Ṣuḥuf kept in ḥafṣah’s custody.44 According to the second version, ʿUthmān authorized a fresh compilation using primary sources and then double-checked it against the Ṣuḥuf.45 In either case the Ṣuḥuf played the major role in the new compilation, which came to be called the Muṣḥaf.

Al-Barāʾ reports the first version of the story:

So ʿUthmān sent ḥafṣah a message stating, “Send us the Ṣuḥuf so that we may make perfect copies and then return the Ṣuḥuf back to you.” Ḥafṣah sent it to ʿUthmān, who ordered Zayd ibn Thābit, ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr, Saʿīd ibn al-ʿĀṣ, and ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥārith ibn Hishām to make duplicate copies. He told the three Qurayshī men, “Should you disagree with Zayd ibn Thābit on any point regarding the Quran, write it in the dialect of the Quraysh, as the Quran was revealed in their tongue.” They did so, and after they had prepared several copies ʿUthmān returned the Ṣuḥuf to Ḥafṣah.46

Ibn Ḥajar comments on the Caliph’s choice of the Qurayshī dialect: since all Arabic dialects would be of equal difficulty for non-Arabs who desire to read the Quran, the most favorable choice is the Qurayshī dialect, because that is the dialect in which the revelation (waḥy) was revealed.47

SANCTIONING OF THE MUṢḤAF

The definitive copy of the Muṣḥaf was read to the Companions in ʿUthmān’s presence.48 When the final recitation was over, ʿUthmān dispatched certified duplicate copies to be made for distribution throughout the provinces of the Islamic state. People were also encouraged to make duplicate copies of the Muṣḥaf for their own personal use. Yet, after this process was over there remained the unfinished task of taking out of circulation other existing copies. There was now no need for the numerous fragments of the Quran in public circulation, so with unanimous consent all such fragments were burned. According to Muṣʿab ibn Saʿd, the people were rather pleased and no one voiced any objections,49 a statement seconded by ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, who declared that everything was done “in clear view of us all [i.e., with our consent].”50

It is in fact known that ʿAlī himself was often consulted when the definitive Muṣḥaf was being prepared. Shiite sources also assert that ʿAlī himself had a written copy of the Quran, which was also used to compare various passages. To this day there are in several libraries pages of the Quran whose calligraphy is attributed to ʿAlī, who is in fact considered the creator of the Kūfic style of Quranic calligraphy by Islamic master calligraphers.

According to one report, six certified copies of the ʿUthmānī Muṣḥaf were penned, of which five were dispatched to various parts of the Islamic state and one kept by ʿUthmān himself for personal use. With each dispatched copy the Caliph also sent along a qāriʾ (“reciter”). The reciters included Zayd ibn Thābit, sent to Madinah; ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Ṣāʾib, to Makkah; al-Mughīrah ibn Shihāb, to Syria; ʿĀmir ibn ʿAbd Qays, to Basra; and ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Sulamī, to Kufa. But why send along a reciter? Sending a scholar with every muṣḥaf emphasized that proper recitation was learned through direct contact with teachers whose transmission channels reached back to the Prophet himself and could not depend simply on the written script and spelling conventions.51

Accompanying each certified copy was also ʿUthmān’s decree that all personal fragments of the Quran differing from the Muṣḥaf be burned.52 Ibn Ḥajar mentions that despite the use of the word “burn” in the decree, it is possible that individuals erased the ink rather than burning the fragment.53 Radiocarbon dating of a recently discovered muṣḥaf palimpsest (referring to a parchment whose writing has been washed off or erased and then written over, creating two different layers of text), has revealed with 90 percent confidence that the palimsest can be dated earlier than 34/654,54 placing it very close to the end of ʿUthmān’s reign. It is possible that this parchment was one of those fragments that was erased (in lieu of burning) and copied over with the text from the official Muṣḥaf.

The second reason for sending a qāriʾ with each copy was so that no recitation would be made of the text that was counter to the written script of the Muṣḥaf. ʿUthmān’s script and spelling became the new standard, and from then on all reading and learning of the Quran by Muslims has been always based on the text thus established by ʿUthmān.

© Muhammad Mustafa al-Azami

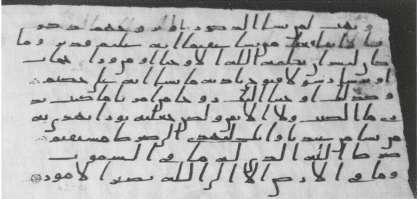

A parchment of a palimpsest muṣḥaf (Stanford ’07 verso).

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ʿUTHMĀNĪ MUṢḤAF

The official copies made under ʿUthmān’s supervision were largely consonantal, frequently dropping vowels, and with no dots. Being devoid of dots, the text could easily be read in many erroneous ways, and some orientalists claim that that is indeed what people did (see “Origin of Multiple Readings,” below). But ʿUthmān’s objective was precisely the opposite: to eliminate all circumstances leading to disputes in recitation. Sending a muṣḥaf by itself or a reciter at liberty to devise any reading he chose would not have achieved this objective. But by sending both concurrently, ʿUthmān brilliantly achieved the unity he sought to establish within the Islamic community.

It was not long before contemporary scholars began inspecting these official muṣḥafs. Many traveled to the various locales that had received a copy and began scrutinizing them, letter by letter, to uncover any inconsistencies between the copies. Their conclusion was that the six ʿUthmānic muṣḥafs were almost perfectly congruent with each other. The minor deviations between them can be summarized as follows: (1) an extra alif in 11 places; (2) an extra wāw in 8 places; (3) an extra character (other than alif or wāw) in 16 places; (4) a character in place of another in 6 places; (5) an extra min in 9:100; and (6) an extra huwa in 57:24.55 These amount to a mere 43 letters out of the 323,671 letters in the Quran. Moreover, none of the variants cause any changes in the meaning of the verse. Interestingly, however, keeping these “multiple readings” was deliberate. While preparing the official copies, Zayd, finding in each case two readings to be authentic and of equal status, retained them in different muṣḥafs.56 Relegating one of them to the margins would have implied inferior status, and placing them side by side would engender confusion, but by placing each variant in a separate copy he gave both readings their just due.

EXTANT MUṢḤAFS ASCRIBED TO ʿUTHMĀN

According to many scholars, the official copies ʿUthmān dispatched are long lost, but in various parts of the world there are a handful of copies of the Quran that are popularly attributed to him, each bearing the label “Muṣḥaf of ʿUthmān,” though not all scholars agree that they are truly ʿUthmānic. They are preserved at the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul; at the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum, also in Istanbul; in Tashkent, Uzbekistan; at the al-Mashhad al-Ḥusaynī Mosque in Cairo; and at the Institute of Oriental Studies in St. Petersburg, Russia.57 Based on the existing description of the ʿUthmānī Muṣḥaf, which none of them fits exactly, the paleographic evidence suggests that these copies of the Quran are from a somewhat later period, possibly the second half of the first century or the first half of the second AH. What is more heartening is that, even though none of them is probably the original of any of ʿUthmān’s six official copies, they all abide by one of the two multiple readings inserted by Zayd ibn Thābit into separate muṣḥafs at each of the forty-three positions mentioned above. The only exception to this fact is the muṣḥaf in Tashkent. In any case there is every reason to believe that these very early manuscripts were copied very scrupulously from the ʿUthmānic muṣḥafs.

Among the so-called muṣḥafs of ʿUthmān, the most celebrated is the one in Tashkent. It is also the one with the richest history and the saddest fate. Initially housed in Damascus, it caught the eye of Tamerlane after he sacked the city, and he had it transported to Samarqand. In 1868 the Russians overran Samarqand and moved the muṣḥaf to the Imperial Public Library in St. Petersburg. As the Bolsheviks advanced near the end of World War I, General Ali Akbar Bashi of the Imperial Army did not trust the young revolutionaries and hurriedly sent it to safety in Tashkent under armed guard. As a result of an 1891 article by a Russian orientalist describing this text, orientalist interest in the muṣḥaf became so pronounced that S. Pissareff opted to publish a full-size facsimile edition. Before doing so, he made the horrendous decision to retrace with fresh ink those folios that had faded over time, in the course of which he introduced many “unintentional” alterations into the text.58 As the text has been corrupted, it is now both pointless and impossible to use it as a serious resource for textual study.

Origin of Multiple Readings

As mentioned earlier, the ʿUthmānī Muṣḥaf was completely dotless and without marks indicating declensions. The Arabic word for “dots” is nuqaṭ, and it is used for referring to skeletal dots as well as diacritical marks; declension marks are called iʿrāb. The former are dots that are placed over or under letters to differentiate them from others sharing the same skeleton, for example, ḥāʾ (ح), khāʾ(خ), and jīm (ج), much like è, é, ê, and ë in the Latin alphabet used in some European languages. Iʿrāb refers to the dots or markings that are used to indicate the sound of short vowels (a, o, i). The position of iʿrāb can also change the meaning of words such as inna (![]() ) and anna (

) and anna (![]() ).

).

Could this dotlessness and lack of declension marks cause divergences in the readings of the Quran? The answer in some cases could be yes if one had only the written text. Clearly a word such as ![]() can be read as ḥamal, khamal, or jamal depending on where the dot is on the first letter or if there is a dot, though not all these words are recognized Arabic terms. In practice, however, the answer to the question is no, because the correct qirāʾah (“recitation”) originated from the Prophet himself and was known to those who were scholars of the Quran.

can be read as ḥamal, khamal, or jamal depending on where the dot is on the first letter or if there is a dot, though not all these words are recognized Arabic terms. In practice, however, the answer to the question is no, because the correct qirāʾah (“recitation”) originated from the Prophet himself and was known to those who were scholars of the Quran.

It must be noted that in the early Islamic period people were not purchasing muṣḥafs casually from the local bazaar and then learning to read them by themselves at their convenience. Verbal schooling from a certified instructor was required. No official reading originated from a vacuum or from personal choice or guesswork. In the case of more than one authoritative reading for a particular word, the source for the existence of the two readings is itself always traced back to the Prophet. Copies of the Quran were later produced with complete dots, markings, and iʿrāb, so that everyone who knew Arabic could read it correctly.

The spread of Islam over the Arabian Peninsula meant the assimilation of new tribes with new dialects.59 For some the Qurayshī dialect proved difficult. The Companion Ubayy ibn Kaʿb reports:

The Prophet encountered Gabriel on the outskirts of Madinah and told him, “I have been sent to a nation of illiterates; among them are the elder with his walking stick, the aged woman, and the young.” Gabriel replied, “So command them to recite the Quran in seven dialects (aḥruf).”60

Over twenty Companions have narrated aḥādīth stating that the Quran was revealed in seven dialects.61 Most agreed that the main objective was to assist those who were not used to the Qurayshī dialect in reciting the Quran. Zayd ibn Thābit said, “The qirāʾah is a sunnah that is strictly to be adhered to.”62 Some dislike the term “variant reading” and prefer “multiple readings,” which is a far more accurate description. The word “variant” arises, by definition, from uncertainty. This is not the case here. As the sole human being chosen by God to receive the Quranic revelation (waḥy), the Prophet Muhammad himself taught specific verses in multiple ways. The doubt factor, which the word “variant” conveys, does not apply here.

But let us for the sake of argument return to the issue of whether dotlessness can cause discrepancy in the reading of the Quran. Many Quranic phrases contextually allow the inclusion of more than one set of dots and diacritical markings. In the vast majority of cases, however, scholars recite them in just one way. When a variation does arise (which is rare), the skeleton of both readings remains faithful to the ʿUthmānī Muṣḥaf, and each group can justify its reading based on a chain of authority leading all the way back to the Prophet. Had reciters been at liberty to supply their own dots and marks, as claimed by some orientalists, the list of variants would run into the hundreds of thousands, if not millions. Consider, for example, the skeletal ![]() . Possible readings are

. Possible readings are ![]() or

or ![]() , which are all legitimate from the linguistic point of view. Going over the entire Muṣḥaf, the Quranic scholar Abū Bakr ibn Mujāhid (d. 324/936) counted roughly only one thousand multiple readings. These are due to the varying placement of dots and diacritical markings on the skeletal backbone of the ʿUthmānī Muṣḥaf. For example, the skeletal

, which are all legitimate from the linguistic point of view. Going over the entire Muṣḥaf, the Quranic scholar Abū Bakr ibn Mujāhid (d. 324/936) counted roughly only one thousand multiple readings. These are due to the varying placement of dots and diacritical markings on the skeletal backbone of the ʿUthmānī Muṣḥaf. For example, the skeletal ![]() occurs in 1:3; 3:26; and 113:2, and contextually it could be read in all three verses as either

occurs in 1:3; 3:26; and 113:2, and contextually it could be read in all three verses as either ![]() (mālik) or

(mālik) or ![]() (malik). However, only in 1:3 is it read both ways (both backed by a valid qirāʾah), while in the other two it is unanimously read only one way. There are thousands of instances where two forms of a word are equally valid contextually, but only one is collectively used.

(malik). However, only in 1:3 is it read both ways (both backed by a valid qirāʾah), while in the other two it is unanimously read only one way. There are thousands of instances where two forms of a word are equally valid contextually, but only one is collectively used.

THE EXAMPLE OF THE WRITING OF ALIF

In Madinah the Prophet employed many scribes, often from different tribes and localities, who were possibly accustomed to varying dialects and spelling conventions. For example, a letter dictated by the Prophet to Khālid ibn Saʿīd ibn al-ʿĀṣ reveals a few peculiarities. The word ![]() (kāna, usually spelled with a kāf, alif, and nūn) is written

(kāna, usually spelled with a kāf, alif, and nūn) is written ![]() (with a waw instead of an alif), and

(with a waw instead of an alif), and ![]() (ḥattā, usually spelled with a ḥāʾ, tāʾ, and alif maqṣūrah) is spelled

(ḥattā, usually spelled with a ḥāʾ, tāʾ, and alif maqṣūrah) is spelled ![]() (with a normal alif instead of an alif maqṣūrah).63 There is no shortage of evidence regarding the variance in writing styles during the early days of Islam. This comes as no surprise when we consider, in our time, the spelling differences, for example, between American and British English.64 Standardized spellings are in fact mostly a modern phenomenon. Variant spellings of individual words were common even in printed books. On the opening page of St. John’s Gospel in the 1526 Tyndale English Bible, we note that “that” is spelled “that” and “thatt” on the same page, “with” is spelled “with” and “wyth,” and “of” is spelled both “of” and “off.”65

(with a normal alif instead of an alif maqṣūrah).63 There is no shortage of evidence regarding the variance in writing styles during the early days of Islam. This comes as no surprise when we consider, in our time, the spelling differences, for example, between American and British English.64 Standardized spellings are in fact mostly a modern phenomenon. Variant spellings of individual words were common even in printed books. On the opening page of St. John’s Gospel in the 1526 Tyndale English Bible, we note that “that” is spelled “that” and “thatt” on the same page, “with” is spelled “with” and “wyth,” and “of” is spelled both “of” and “off.”65

In Arabic, the letter alif (∣) is of particular interest. There are many instances where alif is pronounced but not written. For example, 2:9 in ʿUthmān’s Muṣḥaf is written ![]() while it is actually pronounced

while it is actually pronounced ![]() . Similarly

. Similarly ![]() (al-samāwāt)is mostly spelled

(al-samāwāt)is mostly spelled ![]() , that is, without alif. Most modern printed muṣḥafs adhere faithfully to the ʿUthmānī spelling system and there is a reluctance to deviate from its orthography. Once the famous scholar Imam Mālik (d. 179/795) was solicited for his legal opinion on whether one should copy the Muṣḥaf afresh utilizing the latest spelling conventions; he resisted the idea, except perhaps for schoolchildren. Another aspect of irregularity with alif in the ʿUthmānī Muṣḥaf is that it may be written as a dotless yāʾ, for example,

, that is, without alif. Most modern printed muṣḥafs adhere faithfully to the ʿUthmānī spelling system and there is a reluctance to deviate from its orthography. Once the famous scholar Imam Mālik (d. 179/795) was solicited for his legal opinion on whether one should copy the Muṣḥaf afresh utilizing the latest spelling conventions; he resisted the idea, except perhaps for schoolchildren. Another aspect of irregularity with alif in the ʿUthmānī Muṣḥaf is that it may be written as a dotless yāʾ, for example, ![]() (maʾwāhum). With the oral transmission of the Quran, the pronunciation is never left in doubt even with these irregularities.

(maʾwāhum). With the oral transmission of the Quran, the pronunciation is never left in doubt even with these irregularities.

Even during the lifetime of the Companions a book appeared treating the subject of multiple readings on a small scale. Over time large works came to be written comparing the recitation of famous scholars from different centers and culminating in the work of figures such as Ibn Mujāhid. From the Islamic point of the view the codification of the Quran has been the object of continuous and meticulous study. The traditional Islamic position is not that the history of the muṣḥaf is closed to systematic inquiry, but rather that it has always been subject to such study and that the traditional Islamic account of the transmission and recording of the Quran is the one that is best supported by the available evidence. New theories related to the recording and transmission of the text often are no more than reinterpretations of historical evidence already known to the Islamic intellectual tradition for a millennium, and they are usually based on a set of assumptions brought to the textual evidence rather than deduced in some systematic way from it. Although contemporary scholars outside of the Islamic context have offered a range of imaginative interpretations to get to the “real” Quran, those unfamiliar with the Islamic intellectual tradition should remember that every last “variant” or “alternate reading” used as evidence that the classical Islamic account is inaccurate comes out from the Islamic intellectual tradition itself.66