5

Making Bella Baxter

“GEORDIE GEDDES WORKS FOR GLASGOW Humane Society, who give him a rent-free house on Glasgow Green. His job is to fish human bodies out of the Clyde and save their lives, if possible. When not possible he puts them in a small morgue attached to his dwelling, where a police surgeon performs autopsies. If this official is not available they send for me. Most of the bodies are suicides, of course, and if no one claims them they are transferred to dissecting-rooms and laboratories. I have arranged such transfers.

“I was called to examine the body you know as Bella soon after our quarrel a year ago. Geddes saw a young woman climb onto the parapet of the suspension bridge near his home. She did not jump feet first like most suicides. She dived clean under like a swimmer but expelling the air from her lungs, not drawing it in, for she did not return to the surface alive. On recovering the body Geddes found she had tied the strap of a reticule filled with stones to her wrist. An unusually deliberate suicide then, and committed by someone who wished to be forgotten. The pockets of her discreetly fashionable garments were empty, with neat holes cut in the linings and lingerie where women of the wealthier class have their names or initials stitched. Rigor had not set in, the body had hardly cooled before I arrived. I found she was pregnant, with pressure grooves round the finger where wedding and engagement rings had been removed. What does that suggest to you, McCandless?”

“Either she was carrying the child of a husband she hated or the child of a lover she had preferred to her husband, a lover who abandoned her.”

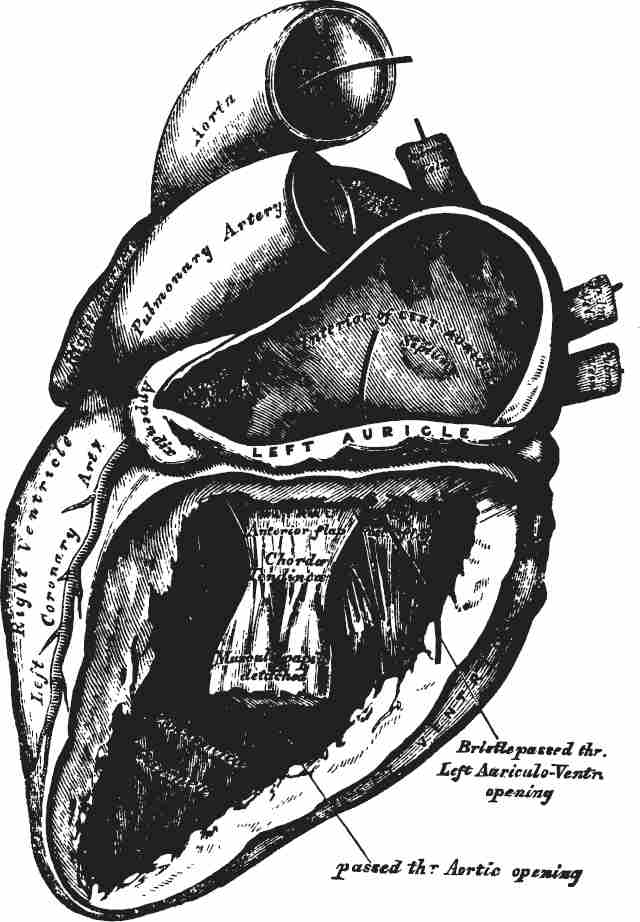

“I thought so too. I cleared her lungs of water, her womb of the foetus, and by a subtle use of electrical stimulus could have brought her back to self-conscious life. I dared not. You will know why if you see Bella asleep. Bella’s face in repose is that of the ardent, wise, sorrowful woman who lay before me on the mortuary slab. I knew nothing about the life she had abandoned, except that she hated it so much that she had chosen not to be, and forever! What would she feel on being dragged from her carefully chosen blank eternity and forced to be in one of our thick-walled, understaffed, poorly equipped madhouses, reformatories or jails? For in this Christian nation suicide is treated as lunacy or crime. So I kept the body alive at a purely cellular level. It was advertised. Nobody claimed it. I brought it here to my father’s laboratory. My childhood hopes, and boyhood dreams, my education and adult researches had prepared me for this moment.

“Every year hundreds of young women drown themselves because of the poverty and prejudices of our damnably unfair society. And nature too can be ungenerous. You know how often it produces births we call unnatural because they cannot live without artificial help or cannot live at all: anacephalids, bicephalids, cyclops, and some so unique science does not name them. Good doctoring ensures the mothers never see these. Some malformations are less grotesque but equally dreadful—babies without digestive tracts who must starve to death as soon as the umbilical cord is cut if a kind hand does not first smother them. No doctor dare do such a thing, or order a nurse to do it, but the thing gets done, and in modern Glasgow—second city of Britain for size and foremost for infant mortality—few parents can afford a coffin, a funeral and a grave for every dead wee body they own. Even Catholics consign their unchristened to limbo. In the Workshop of the World limbo is usually the medical profession. For years I had been planning to take a discarded body and discarded brain from our social midden heap and unite them in a new life. I now did so, hence Bella.”

Like most who listen closely to a tale told in a calm manner I too had grown calm, which helped me think sensibly again.

“Bravo, Baxter!” I cried, raising my glass as if toasting him. “How do you explain her dialect? Is there Yorkshire blood in her veins or do the parents of her brain come from northern England?”

“Only one explanation is possible,” said Baxter broodingly. “The earliest habits we learn (and speech is one of them) must become instinct through the nerves and muscles of the whole body. We know instincts are not wholly seated in the brain, since a headless chicken can run for yards before it drops. The muscles of Bella’s throat, tongue and lips still move as they did in the first twenty-five years of their existence, which I think was nearer Manchester than Leeds. But all the words she uses have been learned from me, or from the elderly Scotswomen who run my household, or from children who play with her here.”

“How do you explain Bella’s presence to them, Baxter? Or are you such a domestic tyrant that your underlings dare not ask for explanations?”

Baxter hesitated, then muttered that his servants were all former nurses trained by Sir Colin, and not surprised by the presence of strange people recovering from intricate operations.

“But how do you explain her to society, Baxter? Are your neighbours in the Circus—the parents of those who play with her—the policeman on the beat—are they told she is a surgical fabrication? How will you account for her on the next government census?”

“They are told she is Bella Baxter, a distant niece whose parents died in a South American railway accident, a disaster where she sustained a concussion causing total amnesia. I have dressed in mourning to support this story. It is a good one. Sir Colin had a cousin he quarrelled with many years ago, who went out to the Argentine before the potato famine and was never heard of again. He could easily have married the daughter of English emigrés in a racial hodge-podge like the Argentine. And luckily Bella’s complexion (though different before I arrested her cellular decay) is now as sallow as my own, which can pass as a family trait. This is the story Bella will be told when she learns that most people have parents and wants a couple of them for herself. An extinct, respectable couple will be better than none. It would cast a shadow upon her life to learn she is a surgical fabrication. Only you and I know the truth, and I doubt if you believe it.”

“Frankly, Baxter, the story of the railway accident is more convincing.”

“Believe what you like, McCandless, but please go easy on the port.”

I refused to go easy on the port. I deliberately filled the glass a second time while saying with equal deliberation, “So you think Miss Baxter’s brain will one day be as adult as her body.”

“Yes, and quickly. Judging by her speech how old would you say she is?”

“She blethered like a five-year-old.”

“I judge her mental age by the age of children she can play with. Robbie Murdoch, my housekeeper’s grandchild, is not quite two. They crawled around the floor very happily till five weeks ago, then she began to find him boring and developed a passionate admiration for a niece of my cook. This niece is a bright six-year-old who, after Bella’s novelty wore off, finds her very boring. I think Bella’s mental age is nearly four, and if I am right then her body has stimulated the growth of her brain at a wonderfull rate. This will cause problems. You did not notice it, McCandless, but you attracted Bella. You are the first adult male she has met apart from me, and I saw her sense it through the finger tips. Her response showed that her body was recalling carnal sensations from its earlier life, and the sensations excited her brain into new thoughts and word forms. She asked you to be her candle and candle maker. A bawdy construction could be put on that.”

“Havers!” I cried, appalled. “How dare you talk of your lovely niece in that monstrous way. Had you played with other bairns when you were young you would know such talk is commonplace childhood prattle. Come-a-riddle come-a-riddle come-a-rote-tote-tote, a wee wee man in a wee wee boat. Willie Winkie runs through the toon in his night goon. I had a little husband no bigger than my thumb. Little Jack Horner stuck his in a plum. But how will you educate Miss Baxter if she outgrows this pleasant state?”

“Not by sending her to school,” he said firmly. “I will not let people treat her as an oddity. I will shortly take her on a carefully planned journey round the world, staying longest in the places she enjoys. In this way she will see and learn many things by talking to folk who will not find her much queerer than most British travellers, and charmingly natural when compared with her gross companion. It will also let me remove her quickly from attachments which look like becoming romantic in an unhygienic way.”

“And of course, Baxter,” I told him recklessly, “she will be wholly at your mercy with no public opinion to protect her, not even through the frail agency of your domestic servants. When we last met, Baxter, you boasted in the heat of a quarrel that you were devising a secret method of getting a woman all to yourself, and now I know what your secret is—abduction! You think you are about to possess what men have hopelessly yearned for throughout the ages: the soul of an innocent, trusting, dependent child inside the opulent body of a radiantly lovely woman. I will not allow it, Baxter. You are the rich heir of a mighty nobleman, I am the bastard bairn of a poor peasant, but between the wretched of the earth there is a stronger bond than the rich realize. Whether Bella Baxter be your orphaned niece or twice orphaned fabrication, I am more truly akin to her than you can ever be, and I will preserve her honour to the last drop of blood in my veins as sure as there is a God in Heaven, Baxter!—a God of Eternal Pity and Vengeance before whom the mightiest emperor oh earth is feebler than a falling sparrow.”

Baxter replied by carrying the decanter back to the cupboard where he had found it and locking the door.

I cooled down while he did this, remembering I had stopped believing in God, Heaven, Eternal Pity et cetera after reading The Origin of Species. It still seems weird to recall that after unexpectedly meeting my only friend, future wife and first decanter of port I raved in the language of novels I knew to be trash, and only read to relax my brain before sleeping.