On my trip to Alabama, Johnny Sandlin drove me to Muscle Shoals to visit FAME (Florence Alabama Music Enterprises), the legendary recording studios where my father’s life really started to change. We passed through the marshy flatland that mirrored the vast sky above. Fenced cotton fields and neatly groomed farmland, brick churches every other mile, and a smattering of small houses rested quietly beside our two-lane road. Picturing Duane in this rural, peaceful place after the constant action of Los Angeles wasn’t easy. I figured you had better know how to make your own fun if you move to Muscle Shoals.

FAME Studios is located in the same building it was in in 1968. Walking inside, you hear the voices of Etta James or Clarence Carter singing through the little speakers above the door as a stream of hits plays all day. FAME has two studios, A and B, each room partially paneled in wood, with high, angled ceilings, acoustic tiles, and curtains to buffer sound. Control rooms are visible through large panes of glass. Rick Hall’s office is upstairs.

“When I was much younger, much younger,” Hall tells me when we meet, “I was hot as a pistol. I had no time for Duane. I had no time for anybody. I was that guy in Muscle Shoals, Alabama.

“I cut the first hit record here. It was all black music. It was Arthur Alexander, that was the first one. Then Jimmy Hughes’s ‘Steal Away,’ Joe Tex, Joe Simon, Aretha Franklin, Etta James, Wilson Pickett, Clarence Carter, and Otis Redding. Anybody who was anybody—they were here.

“Duane had separated from his brother. He considered his brother to be very talented, but somebody you couldn’t deal with. He was tough and he didn’t understand business. He was a kid. Duane from the first was my guy and I was his guy. We loved each other. We cared about each other. He came here and said, ‘I want to become a studio guitar player.’ My ankles bled most of the time, because he was nipping at them. I’d think, ‘Come on! Back off! Don’t breathe on me!’ And then he’d hug my neck and I’d hug his. I cared for him.”

Rick settled back behind his wide desk and jumped right in at the beginning.

“ ‘Duane, I have six guitar players. The last thing I need is a guitar player. I’ve got guitar players running out my ears. I don’t have a place for you.’

“ ‘Would you mind if I just stayed around and kind of worked my way in somewhere? I will set up a pup tent in the parking lot. I want you to use me on something.’

“ ‘Make yourself at home,’ I said.

“ ‘I’m gonna burn some ass, you will see!’ Duane shook my hand and winked at me.”

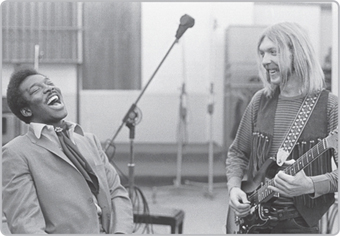

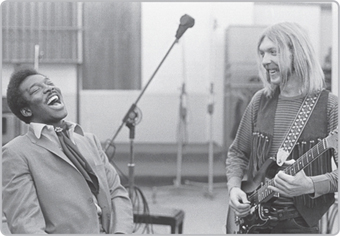

Duane loved Clarence Carter and when he heard he was coming in, he turned up the heat and Rick told him he could play on the session. They cut a real blues thing called “Road of Love,” and Duane’s playing really shined. Rick was very impressed. In the middle of the song, Carter even sang out, “I like what I’m listening to right now,” after Duane’s slide solo, a blast of passion in the middle of a simple, funky groove. Duane brought that track to life.

Duane said, “The blues are coming back, Rick. It’s gonna be big and you can be big with it.”

“I’m tired of that shit,” Rick said.

Rick was a rhythm-and-blues innovator: horns, funky piano, and an all-important singer out front, bursting with personality to really put a song across. Duane was from another planet, walking in with tight striped pants and bowling shoes, his hair down to his shoulders, looking like it had never met a brush. He played so loud the shingles on the building rattled. Rick would say, “You’re killing me! I’m gonna go deaf!” And Duane would say, “But that’s it, Rick! The strings sound wider when you play loud. It overdrives the speakers in the amplifier and gives you that growl!”

Duane’s talent was undeniable, and the artists who came through and the guys in the rhythm section respected his ability and enthusiasm right away. Rick signed Duane to a contract, but to Rick’s mind, Duane’s solo project was a mess.

Duane wanted to sing, play guitar, and do everything on his own, but he didn’t seem to be getting anything accomplished. He bedded down in Studio B and he’d sleep half the day away and smoke pot in the alley for the other half. They were in a dry county, for God’s sake, even alcohol was forbidden, and he’s lighting up without a care in the world.

Duane convinced Rick to do seven or eight sides of him singing. Some weren’t quite finished when Rick’s close friend Phil Walden came by to check him out. Phil had been Otis Redding’s manager from the beginning of his career, when Otis was playing at school dances in their shared hometown of Macon, Georgia. Phil was a self-made industry man, a kingpin in Macon who signed promising black artists and worked hard to help them cross the color divide. Phil managed musicians and brought them to Rick to record. He and Rick shared a sense of themselves as Modern Southern Aristocrats and they had found incredible success. Phil saw Duane’s value right away, a white kid who could bring southern music into the rock scene; he was a dream come true.

“Rick, you’re going to be rich!” Phil told him. “You’ve just got to hang in there. Just go in the studio, light up a cigarette, get you a Coca-Cola, turn the machine on and sit back, and when he gets ready to do something, let him do it, and don’t worry about it.”

Rick was not built that way. He lived an orderly life and ran an orderly studio. His sessions ran like a well-oiled machine. The rhythm section came in day after day and worked regular hours. They knew those rooms intimately and how to get the best sounds out of them, and they wasted no time fussing with any of it. Then here was this skinny dude, curled up on the floor taking a nap in the afternoon. Rick would wake Duane up and Duane would say, “The stars aren’t lining up.”

Twiggs Lyndon was one of the first people Phil Walden introduced to Duane. The buzz about the white guitar player who could really play the blues had reached Twiggs in Macon, and he traveled to FAME to check it out. Twiggs was a musical purist, raised on the real shit; he had no interest in rock and roll, and he truly believed black musicians were tapped into a source white players would never find. Twiggs was a tenacious and brilliant guy who worked as a road manager for several of Walden’s artists. He was born and raised in Macon, although he was cut from a different cloth from most of Macon’s upright citizens. He walked with the swagger of a cowboy and dressed the part, too. Twiggs wore a cowboy hat and a long ponytail, a holstered pistol on his belt. He tucked his blue jeans into knee-high boots. To top it off, he raced through town in a beautiful 1929 Ford Opera Coupe, which he treasured. He had bright blue eyes and great white teeth that flashed in a winning smile. He could talk his way into and out of almost any situation.

Little Richard gave him his first job in the music business when he was not long out of high school and had gone AWOL from the navy. Twiggs met the legendary R&B powerhouse at a club in California and told him they were from the same hometown. Twiggs offered his services doing whatever Little Richard needed doing. The story goes that Little Richard gave Twiggs a suitcase full of money and told him to bring it back the next night, and when he did, without a single bill touched, he was hired on the spot.

Duane flat out blew Twiggs’s mind. He almost didn’t have words for the way Duane’s playing made him feel. In his experience, no white musician he had ever heard was able to play with the soulful feeling that Duane conjured. He said that the first ten minutes he spent in Studio B hearing Duane jam made all the bullshit he had been through in the music business thus far well worth it. He made up his mind right then and there that Duane was his way forward. Just hearing him play would be payment enough for whatever Duane’s band would need.

Rick let Duane play with Wilson Pickett. Rick and Pickett had listened to a bunch of songs, demos from sixteen writers out of Memphis and more in Alabama, but they still didn’t have that one song that felt like a hit.

“Pickett was brutal with songs,” Rick explained. “He’d reject them and was apt to throw the guy who wrote it out and whip his ass. That’s why we called him the Wicked Pickett. But he loved me, and he liked Duane.”

It was Duane’s idea that Pickett record “Hey Jude.”

“Would you stop that? That’s the craziest thing I ever heard in my life! That record is number five this week with a bullet and will be number one in the next two weeks and will be there for eight weeks. And we’re going to cover the Beatles with Wilson Pickett in Muscle Shoals, Alabama?” Rick fairly shouted.

“That’s exactly why we need to do it!” Duane said. “We are going to let the world know we’re not afraid to produce anything on anybody. We’ll cover it and it’s going be a big hit!”

Pickett and Rick laughed and told him he was crazy, but then he started to play the riff, and it seemed like a different groove. Pickett warmed up to it and Rick motioned for him to sing along. He sang, “Hey Jew,” and Rick said, “It’s Jude! It’s a name!”

On “Hey Jude,” Duane sounds like he’s being released, clearly excited by the energy radiating from Wilson Pickett. Duane sat on a small amp facing him and they locked in, matching each other’s intensity and driving each other to a fever pitch.

That feeling, of expanding the possibility of a song with his playing, pointed the way forward for Duane. His fierce solo on the end of the cut was the true beginning of his career; everyone who heard it wanted to know who he was. It opened doors for him.

The sessions came one after another after that: Arthur Conley, King Curtis, Soul Survivors, Otis Rush, on and on. And that was just the first month.

FAME Studios ran like a top, clean and even, tight and satisfying. The session players worked regular hours, arriving in the mornings ready to work, and leaving in the evenings, going home to their families. Then Duane blazes through the place, restless and road-worn. Working a routine schedule wasn’t in his nature or his experience. He wanted to jump into sessions, add his own touch, and leave.

Rick wasn’t going to wait around for Duane to find his identity as a solo act. Phil asked Rick what he was going to do with Duane and if he would sell him Duane’s contract.

Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records stayed dialed in to the music that was being made in the South via Phil Walden. Shortly after the song was cut, in the last days of October 1968, Phil played “Hey Jude” for Wexler, who couldn’t believe what he was hearing. Atlantic offered Rick ten thousand dollars for Duane. Rick said, “Write me a check.”

Duane played his final session at FAME in February 1969, and Rick never saw him again. Duane’s continued session work happened in New York or Miami in Atlantic’s studios, or at the studio on Jackson Highway in Sheffield, Alabama, where the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, also called the Swampers, set up their own shop.

Rick ended his story with a sigh. “Duane was always very up. He was not a downer. He was pleasant, soft, and tender. With me being the reverse of all that, we related well. I had had so many conflicts with tough people, but Duane wanted everybody to be in harmony.”

We walked back downstairs to FAME’s lobby; Johnny was waiting patiently for me. I was wrung out like a rag. Rick had told me the whole story almost without taking a breath.

December 6, 1968

Muscle Shoals, Alabama

Dear Donna,

What do you mean, I might not have been good? If I don’t get no sled, fuck Santa Claus!

I’m sorry I didn’t get to talk to you when you called. I called back but you were gone, so I’ll call you again later.

Things here are going very well. In about a month I’m going to start getting my gigging band together. I can hardly wait. I love working in the studio, and it is very valuable experience, but I know I was born to play for a crowd, and I’m really itching to get started. I’m pretty sure the Duck will be with me, and maybe Paul. I hope to get a couple of black cats, too. They’re definitely good to have.

I received some letter from this band that I was living with for a while, and they want me to produce a record for them. I really want to do it, because it’ll give me a chance to help them out, and myself, too. Man, I’m gonna be some kind of busy.

I should be back from New York by the fifteenth, so shortly after that I want you to come down. I can’t set any exact date because I don’t know what might transpire between now and then, but as soon as it’s possible, I want you to be here with me. Find out how long you’ll be able to stay when you come and tell me. I hope a long time.

I’ll close for now. I love and miss you Skinny, and think of you often—

Love, D

P.S. Last Day of Scorpio (ooooo!)

[mailed December 12, 1968]

Sheffield, Alabama

Last Wednesday

This Year

Dear Skinny,

Thank you for your little letter, I didn’t think it was ugly at all; I loved it.

It’s getting real cold here now. We’re supposed to have snow pretty soon. I can’t wait. I’m gonna get a sled for Christmas; Santa already told me.

I just signed a personal management contract with Phil Walden. He used to manage Otis Redding, and he still manages Arthur Conley, Clarence Carter, Aretha Franklin, and a bunch of other people. I’m going to New York in January to cut Aretha Franklin’s new album. I don’t remember if I told you that or not, but I’m so excited about it, I’ll tell you again. I want you to come up as soon as you can after that, because I’ll have plenty of bread and we’ll be able to do whatever we want.

It looks like I’m going to get some time off for Christmas, but I’ll probably go home to see my mom. I still want you to go with me to Miami to the Pop Festival. I’ll make the necessary arrangements.

I’ll write more later. Remember that I love and miss you and want to see you very much. D Duane began 1969 by writing in the new appointment calendar Rick gave him for Christmas, his name embossed on the cover. He wrote:

This year I will be more thoughtful of my fellow man, exert more effort in each of my endeavors professionally as well as personally, take love wherever I find it, and offer it to everyone who will take it. In this coming year I will seek knowledge from those wiser than me and try to teach those who wish to learn from me. I love being alive and I will be the best man I possibly can—

Duane used his appointment calendar for most of January, and then his notes dwindle down to nothing. The empty pages that follow the last entry speak to how busy his life became. You can already see his frustration with the limits of session work in his entry on January 5, when Rick wouldn’t let Duane change his guitar part. It does contain a few entries that recorded significant moments, like his sessions with Aretha Franklin, and his first meeting with both Jerry Wexler and Tom Dowd, the Atlantic president and the legendary producer, respectively, who would become two of the most influential men in his life.

JAN. 2: I spent today driving back from Daytona with Mike and Vance. A nice day.

JAN. 3: Clarence Carter Session. Clarence cancelled today. Moved into my lake crib and it’s a gas. Spent the day fixing it a little.

JAN. 4: Clarence Carter Session

JAN. 5: Clarence Carter Session—Leave for New York for Aretha Franklin session

First part of session terrible. Couldn’t get Rick to accept new idea for guitar parts. The other cats said I was learning fast when this happened. What a drag. (make a car payment)

JAN. 6: Begin Aretha Franklin Session—In New York. Aretha wasn’t available to record today, so we cut this girl Donna Weiss from Memphis. She was a really nice chick, but I’m afraid not much of an artist. I met Jerry Wexler. What a good cat. Saw Tom Dowd and met Arif Mardin and all the Atlantic folks. A damn good organization.

JAN. 7: Aretha showed today. We cut some things. Nice session.

JAN. 8–9: etc etc

JAN. 13: Wait for Sally’s call at Fame

JAN. 17: Been busy and haven’t been keeping this book up. Need to get some bread from sessions soon. Session tomorrow. Received 18 sessions in New York.

Duane was flown to New York City to play with Aretha Franklin at Atlantic Studios.

She didn’t make it into the studio the first day, which was a real disappointment, but when she got there the following day, everything pulled together quickly. She was a country girl in many ways, comfortable in her own skin and easy to be with, but she didn’t waste time. She hit her stride, singing and playing piano. Duane and Jerry Jemmott, the bass player who was already legendary for his powerful, fluid, and funky session playing, were set up in front of Aretha’s piano, facing away from her behind baffles to keep their sounds clean.

The songs they were working up were closer to pure blues than any other work Duane had done for Atlantic. He pulled back and let a single note ache, resting on his warm tone and touch. The sound of his slide was well suited to her tone; their interplay was a conversation. Duane was confident enough to echo the feeling and richness of her voice. When he was done with his part of their session, he went out and bought a bottle of wine, returned to the control room, and listened to Aretha sing out for the rest of the night. It was an incredible experience for him.

While he was in New York, he went with Jimmy Johnson, a fellow studio guitarist at FAME, to see Johnny Winter play at the Fillmore East. Johnny was playing great, and Jimmy loved it, but Duane seemed restless and distracted. He leaned in to Jimmy and said, “Just you watch, this time next year it’s going to be me and my band up there on that stage.”

Jackie Avery was a singer and songwriter working at Redwall, a recording studio Phil Walden had built and dedicated to the memory of Otis Redding in Macon, Georgia. Some of his songs made their way to Muscle Shoals. He was hoping a song of his would end up on Duane’s solo album. When Duane heard the demos, there was only one element that stood out—the rhythm of the drummer. Whoever he was, he had a whole other sense of timing. He was moving everything forward without force, but in a kind of shifting changing progression that was both reliable and surprising. Duane couldn’t tell if this cat knew what he was doing and was amazing, or if he was getting into that sweet current accidentally. Either way, that drummer had potential. His name was Jai Johanny Johanson, also known as Jaimoe.

Jai Johanny was from Gulfport, Mississippi, by way of the moon. When he was in high school, he found a buried treasure in the school library and came to believe it was sent there by God just for him, via the U.S. Postal Service: Down Beat magazine. The magazine revealed the wider world: Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and more. It was filled with sharp-dressed black musicians with goatees and little glasses, berets and Mohawk haircuts, pressed suits and smiles. Jai found himself a pair of clear glasses without prescription lenses and wore them as a talisman, a taste of cool to call his own. He even shaved the sides of his head into a Mohawk.

Jai Johanny played a drum in the marching band. He practiced next to the football field and watched the team run in swerving patterns, tackling each other and sweating, and it felt like he was missing out. He looked down at the still, pocked white circle of his drumhead, and the bandleader, Mr. Willie Sydney Farmer, saw him.

“Go play football if that’s what you feel like doing,” Farmer said.

Jai Johanny lasted three days at football practice and then returned to the band room ready to learn. Football was something he could figure out how to play, but drumming felt like a riddle that kept shifting. Farmer played Charlie Parker albums for Jai Johanny, engaging his ear on a deep level.

A few years later, when Jai Johanny was playing in a nine-piece band fronted by Otis Redding, Otis told him he needed to learn about time. He was rushing the beat, he said. Jai Johanny couldn’t feel it happening. His next gig was playing with Joe Tex, who fired Jai Johanny three times. After the third time, Jai went home and turned the washhouse behind his grandmother’s house into a studio. He set up his kit and a record player and listened to John Coltrane. He played along with the music, five, six, seven hours a day. One afternoon, he was playing and hit the zone. He can’t say what was different or why it happened that day, but he hit a point beyond which everything became clear. He could not make a mistake if he tried, and time as he once chased it disappeared. He was the time. It was in him.

Charles “Honeyboy” Otis played drums with everyone—Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker, so many players a list would be too long—and he took Jai Johanny under his wing. Jai could rely on him and look up to him. He listened carefully to the things Honeyboy told him. When Jackie Avery told Jai that he needed to go hear a white guitar player who was working at FAME Studios, Jai remembered something Honeyboy once said to him. He said if Jai Johanny wanted to make good money, he needed to find some white guys to play with. Instead of heading to New York to play jazz, which was his dream, he decided to head to the Shoals and meet Duane Allman. He could go to New York a little later.

When Jai Johanny Johanson walked into FAME and introduced himself to Duane, it changed both of their lives. Jai was every inch the rebel Duane was, and they recognized each other as kindred spirits before they played a note together. Jai had the physique of a bodybuilder from working out with railroad ties when he couldn’t afford weights. He wore round sunglasses, a string of beads around his neck, and a close-cropped natural haircut. He was a bohemian, tuned in to improvisational jazz, and had spent years holding it down behind some of the best R&B acts in the world.

He and Duane jammed together in Studio B, and Jai Johanny moved into Duane’s cabin by the lake right away. He brought albums by John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and together he and Duane began to explore the universe. Neither of them had ever played the way they were playing together. Each one led, then followed, the music expanding around them like an endless field of play. It was a joyful, powerful experience to play with another man who didn’t impose limits on himself. They improvised, feeding off each other’s energy. From the first time they played together, they were close as brothers.

Duane wanted to get Jaimoe and Berry Oakley together as soon as possible.

He was feeling confined by the daily routines of session work, even though he was playing with some of the most talented musicians in the world. David Hood on bass, Jimmy Johnson on guitar, Roger Hawkins on drums, Barry Beckett and Spooner Oldham on keys: Those session cats were undeniable, and they made the best-sounding records anyone could ever want to hear. The experience of playing beside them had shown Duane what he could handle. He had learned how to get the sound he wanted out of his guitar. His tone was leaps and bounds closer to the sound in his mind. But all those guys were too comfortable. They were living like all the other working stiffs, day in and day out. Duane needed an audience. He needed to move people. He needed to move, period.

The Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section had shown him that he played best when he played with the best. He wanted to keep that feeling of being driven to the edge of his gifts by the players around him, and the cats in Jacksonville had that ability. When Berry came to jam, their vibe flowed right away, with wild, powerful riffing that scared the other studio players in the building. No one else would pick up their instruments and sit in with them; they were grooving on a whole other level. They followed each other into new musical territory none of them had been able to reach alone.

In January 1969, Donna flew to Alabama to visit Duane. It had been months since they had been together in Nashville and she was nervous. Duane picked her up in the Dogsled, a white two-door Ford with a black hardtop that used to belong to Rick. He traded for it by playing guitar. Duane could talk anyone into anything.

He had to go back to the studio, so Donna waited for Duane in the diner of a motel near FAME Studios, where he was in a session. She sat alone and ordered a cup of tea, feeling like a real lady. When it came, she poured in the milk and squeezed a slice of lemon into her cup and was disgusted to find something was wrong with it. She sent it back and asked for another cup. She did this twice more before the waitress explained that she should choose one, milk or lemon, since both together would curdle.

On the way home, they heard the high moan of a freight train rolling across the narrow road. Duane, Donna, and Jai Johanny were sitting shoulder to shoulder on the bench seat of the car. The train’s whistle rose round and clear in the air as if blown through a horn’s brass body. My father asked Jai what key it might be in, that perfect note? He guessed G sharp and the train passed on into the Alabama night. My mother was eighteen years old that winter. This moment stayed with her, proof of Duane’s musician’s ear. He heard the world blowing cool licks all around him. He saved them up and gave them back, streaming freely out of his guitar. She watched it happening, his inspiration forming, and his strength gathering.

Duane’s cabin by the Tennessee River was small and very homey. He had painted a winding vine of colorful flowers on the paned windows of the French doors between his bedroom and the living room and hung an Indian tapestry on the wall. Donna leaned against a post of Duane’s four-poster bed and described a passage she had read from Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet.

Give your hearts, but not into each other’s keeping.

For only the hand of Life can contain your hearts.

And stand together yet not too near together:

For pillars of the temple stand apart,

And the oak tree and the cypress grow not in each other’s shadow.

She described how love could be between them, how they could stand beside each other like two pillars, not leaning or overpowering, but together. She could see by the look in his eyes how impressed Duane was by this idea, and she panicked for a moment. She did not completely understand the words she had just said.

Donna was still and quiet; a world of words could be imagined in her silence. Her eyes were guarded, as difficult to read as the flat glass eyes of a doll, but her lips were by turns nervy and tight, occasionally venturing between her teeth, where one cheek would pinch back into a half smile of distress. She wasn’t going to give in to Duane right away; he could tell. She ran the back of her hand against his cheek, like a gorilla preening her mate. He reached toward her and stroked the back of his hand against her cheek, his Gorilla Girl.

So many things went unsaid between them, and it was better that way. He seemed to know her thoughts. They lay quietly, curled around each other, and talked about what they would be like as parents if they had a child someday. Duane joked that he would be so hip, he’d give his daughter’s boyfriend a key to the house. Donna squeezed his cheeks together and said, “Say funny bunny.” Through his squished lips he said “Fuck you,” laughing, and they rolled together on the bed. Their thin bodies wound around each other in light sleep, folded thigh to thigh. His fingers moved even while he slept, pushing the patterns of invisible chords against Donna’s skin as he dreamed, his body spooned around hers.

The next morning, he jumped out of bed and began to write “Happily Married Man,” a mean little early rock-and-roll riff with tough and funny lyrics: “My new old lady is out of sight, loving me every day and night. Oh, I haven’t seen my wife for two or three years, I’m a happily married man.…”

Donna smiled, slipping his blue jeans on. They fit her perfectly.

Berry was traveling back and forth between Muscle Shoals and Jacksonville, returning with stories and tunes they’d been working on for Duane’s solo album. He was especially excited about the jams he and Duane had with Jaimoe. He told Linda about this tall pretty blond girl Duane had there with him and how he really seemed to be into her. He knew she and Linda would love each other.

When Donna got home to St. Louis two weeks later, everything felt empty and small. Then a letter came and she held it against her, ran to her room, and closed the door. A delicious ache suffused her chest and raced in tingling streaks through her arms and legs, as if every place he had ever touched her were suddenly alive in the sight of his words. If she had ever doubted what this was, she was sorry, because of course this was love. Lying on her bed, she read:

February 4, 1969

Muscle Shoals, Alabama

Skinny Gorilla Girl That I Love,

You’ve been gone three hours now, and I’m nice and drunk trying not to remember that you’re gone. I thought about cutting my house in half and sending half to you so at least we’d be under the same roof, but my heart’s aching so bad I don’t think I could pull a saw to do it. Jai Johanny took two of those blackbirds and he’s really flying and doesn’t know it; what a groove. He’s sure a fine friend. I sure do love you and miss you and I just wish that this pen would say what I want to say. Oh mama, I need you so bad this minute I could bust. Don’t ever make me watch you leave me again. I don’t think I could handle it at all. I’d better quit this before I get in my car and come after you.

I’ll Love You Till

There’s No Till,

Duane

Duane sat on the bank of the Tennessee River, high and feeling so at ease. The sun weakened into pale syrup by the water’s reflection, the trees murmured and shimmied, everything was encouraging a sense of completeness. The little bottle on his finger was cool and thick. There was a world of sounds between the known chords, whole realms beyond the clean and distinct notes found by pressing and strumming alone. These fluid cries felt so true and sad and human to him: odd notes, long notes, voices pulled out of his hand’s movements. The river smiled up at him and the trees applauded Duane sliding home.

He grinned and ran his calloused fingers over his mustache and rough cheeks. He needed a shave. He looked over his shoulder to Jai Johanny, who was growing thick roots into the ground around the bend. His small leather hat was over his eyes and the corners of his mouth formed a sleeping frown. Jai Johanny’s fingers were interlaced over his chest and spots of sun flickered over him like blown bubbles on the breeze.

Duane played the opening riff of “Statesboro Blues” as Jesse Ed Davis played it, over and over with the stamina of an athlete and the monomania of an addict, the siren call, then the quick run of notes flowing; every change, at first as jagged as rock, was soon worn smooth by his fingers.

Songs are maps, and once you have traveled the route they describe, you can find your way in daylight or darkness alone, no longer thinking as you point yourself toward home.

Duane found his sound at the water’s edge. It was resting in his hands.