The Allman Brothers Band album did not sell as well as everyone had hoped, but it was a critical success. Rolling Stone magazine’s legendarily tough and irreverent Lester Bangs called it “consistently subtle, and honest, and moving.” The band was utterly committed to playing; sales were not a serious consideration to them. They were already working on songs for their second album while playing more than three hundred shows in 1970. They were tireless.

On the road, the Brothers found parks to play for free on days between booked gigs. They traveled with a bin full of bright orange extension cords that connected into hundreds of feet of flowing current. They would find a willing neighbor who would let them plug in, and they’d find a hippie kid willing to stand by the point where the cords crossed the road and pay him a couple of joints in return. They were not always welcome to stretch out and play as long as they liked. Once in Audubon Park in New Orleans, the police came and unplugged Duane’s amp to stop the band from going over the park’s 7 P.M. curfew. Red Dog plugged him back in and ran like hell, to bait the cops into chasing him so the band could finish their set.

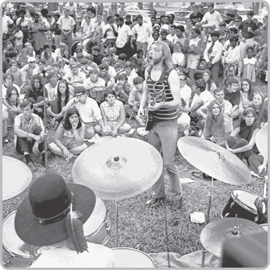

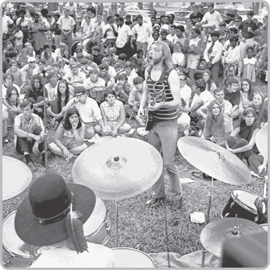

When they were home on a weekend, they’d go to Piedmont Park in Atlanta. The Piedmont Music Festival started out as a casual drop-in jam during the band’s first months in Macon. Folks gathered naturally, until there were hundreds of people spread out in the grass around the musicians. It became a steady weekend gig during the band’s first summer together in 1969, and the crowds swelled to the thousands. By the middle of 1970, it had grown into a proper festival with a stage, a generator, and dozens of other local bands.

To play with the sun on your shoulders, your friends sitting around, thousands of kids gathered peacefully together, was a beautiful thing. It was so chilled out, the police even seemed to enjoy it, and there were never any hassles. The wives and kids would come, too, and that was rare. Berry and Duane didn’t really want Linda and Donna out at concerts, never on the road. They wanted them to stay safely tucked away in Macon, taking care of their babies. But when they played in Georgia, it was a different deal and the wives got to share in the music.

Duane liked to check out other local bands, and one that really caught his attention around this time was the Hampton Grease Band, fronted by Bruce Hampton, a young man everyone called the Colonel. They looked fairly clean-cut, with side-parted hair and suit jackets, but once they started cooking, it was a wild show. Bruce would raise his arms to the sky and preach, dance, and play guitar in completely unpredictable and accomplished improvisations. The music was jagged and jarring one moment, fluid and bluesy the next. Duane saw the bravery and the musicianship in it. He introduced Bruce to Alan Walden, Phil’s brother, at Capricorn Records, and they inked a deal for a record. Duane didn’t give anyone a choice about it. He told Walden to sign them and he did, even though he didn’t have a clue where the Hampton Grease Band was coming from.

Duane was always keen to help musicians he believed in and he made good on his promises. “Duane made you want to give everything,” Thom Doucette said. “When he laid it down, it stayed down, and he was seldom wrong. He was twenty-three going on fifty. The vistas were huge, and it was never about money. Duane wouldn’t waste his energy on petty shit. If there was a problem, it was out in the open and over in a hot minute. Duane was right up in your face; there were no corners or dark spots. If there was a problem with Gregg, it could go on for years.”

Rock festivals were a growing venture in the summer of 1970, and the Brothers played two back-to-back in July: the second annual Atlanta Pop Festival and the Love Valley Festival in North Carolina. The events felt like natural extensions of the free park concerts, and they were often so overwhelmed with crowds, they became free by default when the gates were crashed.

The second Atlanta Pop Festival took place July 3–5 in a soybean field beside the Middle Georgia Raceway in a little town called Byron, about ninety miles from Atlanta. The promoter, Alex Cooley, was hoping for a crowd of 100,000, about the size of the first festival he had promoted the year before, but estimates of the crowd went as high as 400,000 people, making the festival one of the largest gatherings in Georgia history. For fourteen dollars you could spend two days seeing B. B. King, Jimi Hendrix, Ravi Shankar, Procol Harum, and a dozen other bands, including the Hampton Grease Band. But soon the plywood fence that had been constructed to contain the festival was trampled as the crowd grew. From the stage, the crowd looked like a roiling, colorful sea. The summer sun was blazing, over one hundred degrees by late morning, and people wandered naked and jumped in the stream by the road to cool off. Tents were pitched under cover of a pecan grove beside the field.

By Friday morning the highway looked like a parking lot all the way back to Atlanta, and Duane was somewhere stranded in the middle of it an hour before he was supposed to be onstage. Willie Perkins was about to lose his mind when he saw Duane strut through the back gate and strap on his guitar moments before the music started. He had abandoned his Dogsled and convinced a guy on a motorcycle to ride the shoulder all the way to the gig. He barely had time to grin in Willie’s direction before taking the stage. There was only one problem. He didn’t have his Coricidin bottle. He must have left it in the car.

The announcer had a question for the crowd: “Does anyone got like a little finger-sized prescription bottle? A glass bottle? Like a pill bottle? Like a Coricidin bottle or something like that? A glass bottle we can slip on a guitarist’s finger? Or a wine bottle with a long neck?” Ellen Hopkins remembers carefully dragging the broken neck of a wine bottle against concrete, trying to smooth the jagged edge. In the footage you can see the rough dark green cylinder on Duane’s ring finger pressing against the strings of his goldtop Les Paul.

The Allman Brothers played two sets, one to open the festival on the afternoon of the third and one to close it on the night of the fifth, and while there may have been more famous musicians on the bill, they were the hometown heroes. Their performance was captured by a film crew, which was a very rare occurrence. Although legal wrangling has kept the footage under wraps for more than forty years, I have seen a small portion of the film and it is the most vivid documentation of the band at that time. It is electrifying. There is even a brief panning shot down a dusty path that shows Linda and Berry walking together hand in hand, smiling and waving to the camera. Linda saw it for the first time only recently and cried in shock and gratitude.

Then the announcer launches into a bizarre riff of his own to introduce them:

You know in Life magazine they had some pictures of the human egg being fertilized and when I was in school they used to give us this shuck that it’s a big race, you know, and the sperm go out and as they race to the egg and the first one to get there goes into the egg. That isn’t the way it happens. Life magazine … this Swedish nurse or Norwegian photographer took pictures of what happens and what really happens is the sperms surround the egg, the female ovum, and they twirl it with their tails at a rate of eight times per minute in this primordial dance, and this actually happens you know, eight times and, eight is the sign of infinity, right, it goes like this, you know, and that’s where we all come from is this dance, so life isn’t a race, it’s not competing with anyone, it’s playing together like all men play together, and these are the Allman Brothers and they play together, Allman Brothers … All Men!

Duane kicks into “Statesboro Blues,” his knees bouncing, while Berry shifts his weight in a sexy shuffle, smiling like a kid. Dickey’s head and shoulders dip, his cowboy hat shielding his face from the sun. The three of them dance with their axes, loose and limber, as comfortable in the flow as swimmers carried by a tide. Jaimoe holds his drumstick at an angle in the jazz style and bites his lower lip in concentration, while Butch looks straight out into the crowd, the smallest hint of anxiety in his eyes as he drives the band forward. You can see how they amazed one another when their faces bloom into smiles of wonder and encouragement.

Gregg sips from a can of Pabst Blue Ribbon and sings without lifting his eyes from his fingers. He looks so young it is startling. Deep into “Dreams,” the crowd below dances in undulating patterns.

Donna was completely overwhelmed by the playing. Duane was on fire; she had never seen him play so freely. When he walked offstage toward her, she tried to find a way to express how the music made her feel but could only say, “You were so amazing.”

Duane bent his head down to her and said quietly, “I’m glad you liked it.”

He retreated to the comfort of a nearby camper and fell heavily asleep. When Donna tried to wake him to watch Jimi Hendrix play, he was too exhausted to move. As she walked back to her spot on the side of the stage, Jimi passed her in the dark with his guitar in his hand and said hello. Duane missed seeing Hendrix play “The Star-Spangled Banner” at midnight under a sky full of fireworks. Just a couple of months later, Jimi was gone.

Two months before, on May 4, a protest at Ohio’s Kent State University against U.S. military operations in Cambodia ended in violence when members of the National Guard opened fire on student protesters, killing four and wounding nine. Kim Payne told me that the only time he ever saw my father completely unhinged with rage was after he read about the killings in the morning paper. To him it was the ultimate breach of trust. He paced and growled and told everyone they had to fight back, to arm themselves and go after them. A fundamental line had been crossed and now it was war. He was breathing fire, and everyone was a little stunned by his passion and menace. He wanted to round up whatever weapons they could find, get in the van, and drive to Washington, D.C. No one knew what to say to calm him back down. He paced and ranted until he wore himself out.

Even if the purpose was peaceful, any large crowd had a quiet undercurrent of tension after Kent State. The news from Vietnam loomed over these gatherings, too. Music was a galvanizing force against violence, and the South was changing because of it. Bands and their multiracial audiences were directly challenging the social conservatism of previous generations. It felt like a major accomplishment to pull off a concert of this size without incident. When Richie Havens played “Here Comes the Sun” to greet the dawn on the final morning, he seemed to be summoning hopefulness for everyone.

Less than two weeks after Atlanta Pop, the Brothers played the Love Valley Rock Festival in Statesville, North Carolina, a western-themed community of fewer than one hundred people in the foothills of the Brushy Mountains. The town was a single block of rustic wooden buildings linked by a wooden walkway and lined with hitching posts; it looked like a movie set, complete with a church and post office, a general store, and an arena where the festival was held. It was the dream of a young man named Andy Barker, who moved his wife and daughter from Charlotte to a country shack and slowly built the town of which he had always dreamed. The music festival attracted an estimated crowd of one hundred thousand people. The counterculture was spreading through the rural South, alarming many locals, and the events were getting national press.

The footage of that day begins with a hazy, sun-bleached moment. Duane leans into the camera for a kiss, and builds to a passionate and expansive rendition of “Mountain Jam.” The camera stays with him, panning between his hands and his ecstatic face. Duane presses the base of his glass bottle high on the neck and the bright shock of birdsong rings out. He switches seamlessly between playing slide back to straight leads, and as the fever begins to break, the melody of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” flows from his fingertips, all gentle sweetness. There are moments when you can see Gregg, Berry, and Butch all watching him as they play. They shift as he shifts and then, just as you think the song is ending, the band takes the melody into a fiery vamp, a country church service turned rocking roadhouse party. The thread never breaks, only weaves in countermelodies until somehow you are back in the psychedelic expanse of Donovan’s pop song “There Is a Mountain.” By the time they touch back down and the end approaches, Butch pounds a powerful pattern on timpani while Duane bows and rocks his guitar again and again, jumping and landing on the final note.

Linda and Donna traveled to North Carolina to join the band as a surprise, and Duane greeted Donna by asking her what she was doing there. The strain of traveling and playing full-out was showing on him and he was drinking heavily, culminating with him peeing in his sleep on their hotel room radiator in the middle of the night.

When things went dark with him, Donna thought Duane could just stop coming home altogether, or he could come home so changed she wouldn’t want him there. She wasn’t sure which would feel worse. This life she had built with him was so fragile.

From the beginning, Duane wanted to know what went on inside her. He wanted to see if he could open her up, and make her yield to him. She always did, but she also had a temper that could flare up in frustration. Duane didn’t seem to understand how close to the bone they were living while the band was on the road. She and Linda would sometimes take the baby carriages and walk all the way across town to ask for money at the Capricorn office. When she tried to tell this to Duane, he cradled her face in his palms and said, “Oh darlin’, the Ladies Auxiliary has gotten hold of you.”

One night that summer, Duane came home from practice after midnight. Donna prepared him a late meal. He was leaving in the morning, just hours away, and she felt an urgency to connect with him. At the very least, she had to be sure she’d have money to buy what she needed while he was away. She asked for twenty dollars, and he scoffed at her. She would never talk back to Duane, or even raise her voice, but she slowly eased his plate across the table and let it fall into his lap. The hot, wet spaghetti dinner soaked his blue jeans, and she didn’t wait to see how he would react. Her chair scraped the kitchen floor, and she quickly stalked upstairs. She positioned herself on the far edge of their bed so the mattress would be between them if he came into the room. She used to wait in the same position for her father to come pounding upstairs when she had done something wrong. She wasn’t sure what Duane would do. He walked very slowly up the steps and stood in the doorway. “I want you out of here in the morning,” he said, then left. Yeah, right, she thought as she listened to his car pull away. He was the one leaving, not her. His absence was just a different kind of slap.

Part of Donna was always waiting for the end to come. Every hard thing that happened seemed an unwelcome portent of his leaving. When she heard what Twiggs had done, her first thought was This will do it. Duane will leave me. It wasn’t a logical thought, but it felt true. The more stress and pressure he was under, the further apart they grew.

The esteemed British producer Glyn Johns had written to Phil Walden to express his disappointment when Jerry Wexler vetoed the idea of the Allman Brothers recording their first album with him in England. “I am sure all will go well with Adrian Barber. In the same token, I still really want to do the second album. By then things should be a lot more straight on my end.” Duane was still interested in working with him, but when the time came to record their next album, the band locked in Tom Dowd and headed for Criteria Studios in Miami in late August 1970.

Gregg wanted to know why they couldn’t work at home. Capricorn was a state-of-the-art studio, right there in Macon. Duane said, “Dig it. This is Tommy Dowd’s sandbox and his toys. Let’s go give it a try.”

The Allman Brothers recorded together in Studio B, the smaller of Criteria’s two studios. They were arranged as they were onstage, Gregg stage right, Duane and Dickey beside him, and Berry stage left. Jaimoe’s kit was behind Duane and Butch’s was behind Berry. The only overdubs that were done separately were Gregg’s vocals and the occasional corrected lead. Their year of heavy touring between albums was evident. They were able to work through songs quickly because they had aired them out live. This made for comparatively short work at Criteria Studios. Their touring schedule continued on. They divided their time working on the album into several sessions whenever they could find a few free days. They had worked up a portion of the new songs on the road, picking melodies on acoustic guitars in hotel rooms, but some things were still to be determined in the studio.

While they were down in Miami recording, they picked up as many Florida gigs as they could. Jo Jane still spent summers in Daytona with her aunt Jerry, and when the band came within a few hundred miles of Daytona Beach, they would spend hours in Jerry’s tiny red Triumph convertible, just to give her the chance to hug the boys and spend a little time with them. The band and crew called Jerry “Mama A” and treated her like a queen.

Jerry and Jo Jane drove to Pensacola in the summer of 1970 for a couple of nights. The band started very late; they had been delayed by their equipment truck breaking down.

They had played only a few songs by the time the midnight curfew struck, and the promoter cut the power. Jo Jane felt an immediate tingle shoot up her spine, thinking, You do not cut off Duane Allman while he’s playing guitar!

The sudden silence created a vacuum in the room, and people gasped, but Jaimoe and Butch kept playing. No longer tethered to the structure of song, they tapped into the oldest, deepest music used to move bodies and send signals, their drums rumbling in the darkness. The crowd stomped and howled while the rumbling drums built, driving tribal rhythm that moved through the room like a wave. It went on and on, as the rest of the band stood by clapping and stomping their feet, until the promoter had no choice but to turn on the juice and let them finish; the kids were going to tear the walls down if he didn’t. The guitars flew back in like birds crying overhead, swooping in to reclaim their stage. Jo Jane and Jerry were amazed by it. The Allman Brothers were literally unstoppable.

(Years later, I asked Butchie if he remembered that night. “Oh, that used to happen all the time,” he said.)

Kim’s main job was maintaining what they called the Wall, the stack of amplifiers that loomed behind the drummers. For the most part, Duane and Dickey maintained their guitars on their own, without help from anyone on the crew, but occasionally something would go wrong and Kim would jump in. He once replaced one of Duane’s broken strings without taking the guitar from him.

“Seriously, Kim? He kept playing while you changed his string?” I asked.

“Yeah, he kept right on playing. I just stayed away from his fingers best I could.”

One night at the Warehouse in New Orleans, they were opening for Pink Floyd, and when they finished their set, the audience went completely nuts. The band played three encores, and still the crowd was cheering and calling for more. The crew cleared the stage, and Pink Floyd’s crew set up their gear, but the crowd was still shouting for the Brothers to come back. Pink Floyd played a song or two, but the crowd would not let go, chanting for the band, so Pink Floyd walked off the stage to wait them out. Kim walked back to the dressing room and asked Duane what he wanted to do. Duane said, “Set it back up.”

The roadies started to roll out the Brothers’ gear, but the Pink Floyd crew asked them what in the hell they thought they were doing. Kim told them the crowd had spoken and the Brothers were going to play another set, but the other crew wouldn’t back down. “Y’all aren’t from around here, are ya?” Red Dog said, and punches started to fly. In the end, the Brothers took back the stage and played an entire second set, including a version of “Mountain Jam” that lasted more than two hours, until the drummers all but collapsed on their kits.

“We would like to keep playing, but we don’t have any drummers,” Duane said. “We’re gonna go drink a beer, and if there’s anybody still here, we’ll play some more.”

The band moved through towns like a storm system, gathering strength as their cool smacked against the heat of the crowd. Callahan sat at the mixing board in the crowd and received the flood of sound from the many mics onstage. He used his ears to bring them into perfect balance. He taped the shows at the soundboard most nights, for the band to listen to later and mark their progress. When the band fully opened up, he would crank up the volume so the music would be felt down to the bone. The players wouldn’t know the difference from the stage, but for the crowd, it was total sensory immersion.

The year on the road had given the band a patina, a dusty, golden sheen. Nothing could shake their laid-back calm. Sometimes they’d sit on the edge of the stage and talk to people in the audience, shake hands, and make jokes; they remained accessible, engaging, charismatic. The Brothers now had a following they could depend on in a growing number of clubs across the country: at the Warehouse in New Orleans, the Boston Tea Party, Ludlow’s Garage in Cincinnati, Fillmore East and West, and on many college campuses. They lived at the pace set by the road. They felt entitled to their fun, as hard as they worked. They fed girls on songs of love, so what did you expect? They were wanted.

The relationships between the women in the Big House were every bit as significant and satisfying as the Brothers’ relationship to one another. Candy, Linda, and Donna worked hard to make a peaceful and lovely home. They cleaned and baked banana bread, and chased the baby girls around. The wonder of being mothers deeply bonded Linda and Donna. Candy was a working woman, out in the town at the boutique all day. Her thing with Gregg was long over; he had lived with her at the house for a time, but he didn’t stay for long. She found a bundle of love letters from other girls tucked in with his clothes in her wardrobe, and that was it. She started seeing Kim. The women would pass a joint in the evening and confide in one another, describing the men’s bodies and comparing their moves, the little things they liked, and they’d lie stretched out on the floor with the stereo turned up, playing the beautiful music the band sent home. The women felt like muses, hearing the love they shared reflected in the songs.

The Winnebago would roar up behind the house and men would pour out, dirty and tired, talking loud in the alley. Donna would hear them filling up the kitchen, and no one would come upstairs to her. Duane would still be out there somewhere, working. He’d have jumped in on a session or stayed in Atlanta. When he finally came home days later, there were no apologies or explanations. Sometimes he would sleep for days and then leave again. Donna knew what Duane expected of her; he wanted silence and stability. He told her to be “quiet as a mouse.” He wanted to come home and find her waiting. When news came through friends that the band was close, she would dress up, clean the house, and cook. Her anticipation was stronger than any other feeling. When he didn’t come home to her, the strain broke something inside her.

If Duane saw anyone in his band losing their way inside of sadness or stress, he would find words of encouragement to pull them out of it. Everyone had to move forward together. He was so adamant about taking care of everyone, in word and deed, that when the stress of his responsibilities showed on him, it was frightening. Even as the band promoted the importance of their families, the two halves of their lives were fitting together less easily all the time.

Duane’s charm and intelligence were being pulled under a wave of arrogance, and dark moods. He would drink to drunkenness and smoke until he could barely keep his eyes open, repeating himself over and over, saying paranoid things that made no sense. Donna was scared. Listening to Robert Johnson in the music room, he said, “Never poison me,” alluding to the story of the Delta blues master dying at the hand of a jealous man who poisoned his whisky after Johnson flirted with his wife. Duane cut his eyes at Donna over the neck of his wobbling guitar, as if she were the menacing one, picking and slurring out lyrics about no-good women and the evil they make men do.

Donna began to wonder how she had gotten here, so far from herself. Duane could be so crass and cold. After playing a show, he told Donna the concert hall had smelled like girls’ wet panties as soon as he struck a chord. He joked that she was lucky I was born with red hair, or he would wonder if I was his, when he knew he was the only man she’d ever been with. Just mean for the sake of being mean.

In a moment of pure exhaustion, he tried to put the pressure he felt into words, saying, “What is this now? I have you and a baby? And I’m gonna die young.”

Women and children were soft and sticky traps. A man would be wise to take to heart the warnings in his favorite blues songs about low-down women. But here is the rough stuff, bitter and strong: the small paper bindles of heroin, line upon line of cocaine, girlfriends in Atlanta and Los Angeles taken out on the road, teenage groupies used up and cast off. They were all so young, I tell myself. “It was a different time,” Jaimoe says to me. The truth of the matter was, only one person was straying, and it wasn’t my mother.

Red Dog said Duane pitched a bitch when he found a couple of needles hidden in the Winnebago, while they were parked somewhere in rural North Carolina between gigs. Duane paced the length of the caravan, holding the syringes by their empty bellies with fire in his eyes.

“Look, I ain’t calling anyone out. I’m talking to everybody. I am gonna say this once. This shit will not fly. I don’t care who is doing this.” He paused and held a point in the air with his eyes resting on his brother’s bent head. “If I see another needle, that’s it. There will be no conversation, no hard feelings, but this shit is out of the question and you will be gone.”

A little while down the road, he and Dickey were having an argument when Duane grabbed his arm, looking for track marks.

“You can say what you think we all ought to do, and I’ll listen, but you’re not going to check my arms,” Dickey said.

Duane apologized the next day. Dickey told him he knew they were all taking things a little too far, and Duane was right to worry. But Dickey was his own man with his own choices to make, and Duane needed to understand that. He wasn’t going to be dictated to that way.

Cocaine, marijuana, and MDA. Soma and sleeping pills and Robitussin AC, mescaline, LSD and mushrooms, whisky, wine, and heroin. You keep phone numbers scrawled on scraps of paper, but soon you don’t have to call. They just come and wait by the back door when you come to town, and enter the backstage rooms smiling wide. You remember the face of the guy in Boston, in Philly, in New York City who knows how to get you what you want. Folded glassine paper sleeves and a tightly rolled bill, hidden needles and a blackened spoon. The ritual of preparation, the private moment with pills rolling loosely in your palm, the cold beer popped open, the warm, half-empty bottle of red wine, a razor tapping gently through a pile of powder, a little spoon or a long fingernail, a deep inhale, and soon you are restored to yourself. A pulsing energy belongs to you, shining from your eyes, and everything is easier. You see the same ease in the faces all around you. The music blooms in your hands and floats above the crowd, and builds to ferocious crescendos that rock your body. You are in it and of it, fed and freed by the music and the high.

Drugs were taking hold in a deeper way, no longer just a diversion or a way to escape the rigors of the road. Along with the inspirational sound of Coltrane and Bird came the darker story of the relationships between the players and heroin. Heroin stood like an unopened door that might lead more deeply into the songs, and soon Gregg and then Duane stepped through it, the entire band of Brothers behind him. Heroin was easily available and cheap, even in Macon. I asked Johnny Sandlin about the effects of heroin on the band and he said, honestly, at least in the beginning, it was mostly positive. Heroin could give you at once a deep feeling of privacy and an expansiveness, an absence of all discomfort, social and physical. All neurotic static cleared. Heroin was a direct channel into certainty. You felt you had what you needed. In the space it cleared, with each player relaxed and vigilant, they could conjure a pillar of fire. My father and all of the members of the band and crew, with the single exception of Butch Trucks, had fallen in love with heroin. The only thing Duane was more enthralled by was cocaine, and the way he was living, the two walked hand in hand, one taking over when the other trailed off. Cocaine was everywhere; they called it vitamin C. It was coming from sources both high and low, in the pockets of both the business moguls and the creeps who wanted a way in the stage door. Duane told Donna they were either up on it or up looking for more. While no one spelled it out explicitly, drugs were often part of the exchange for playing: payment for services rendered, especially in Miami, where the path to South America was worn smooth and easy.

When I first met Jim Marshall, the photographer who took the picture for the cover of At Fillmore East, he told me the familiar story about his great cover shot of the band laughing together. They were all moody and hard to loosen up, until a guy Duane recognized walked by and he ran after him. He returned with a little bag in his palm and a gleam in his eye. Everybody cracked up, and Jim caught the moment.

Jim grabbed my hand, looked into my eyes, and asked me if I’d ever done cocaine. Before I could answer he said in a conspiratorial tone, “Your daddy loved cocaine. He loved it.” He said it like it was personal and important information. Maybe it is.

Donna says she didn’t see any of it; they kept the hardest drugs out of the house. There was in fact a rule about leaving hard stuff in the garages out back. She wasn’t aware of other girls gathering around Duane, either, until she found a love letter from a girl in Boston tucked into the small compartment of his guitar case that read “I’ll never forget the night we spent together.” She had been looking for the signed divorce papers that had finally arrived from Patti. She wanted to show them to Linda. When she confronted Duane, he said, “If you go looking for shit, you’re going to find it.”

Donna never heard the name Dixie, but everyone else did. Dixie and her friends lived in a house on Taft Street near Piedmont Park in Atlanta, and they notoriously welcomed bands that passed through town. They became known as the Taft Street Girls. When any of the Brothers stayed overnight in Atlanta for “business,” it was clear the meetings were taking place in bed. All the girls the band met and enjoyed on the road were an open secret, rarely discussed. Groupies were part of another life entirely—a road perk like a good meal or pocket money, an irresistible comfort—but the proximity of the Taft Street Girls to Macon was troubling.

In what little time the band had when they weren’t touring, they would retreat together to the cabin they called Idlewild South, named after the packed and frenetic New York City airport now known as JFK. People were in and out all the time; the name was apt. They were still at work on songs for their second album, which would be named after the cabin. Out in the country with no close neighbors to complain, they pulled their extension cords out into the yard and played under the blue sky. One afternoon they were running through a new tune while their wives and girlfriends cooked in the little kitchen. “People, can you feel it? Love is everywhere!” The girls couldn’t help but see the irony. Love was getting starved out in Macon, Georgia, so they made up a chorus of their own: “Practice what you preach! Practice what you preach!”

Hard drugs and groupies were there from the first day. I had imagined an early innocence in 1969, when marijuana and marriage were all anyone wanted, but that’s a child’s fantasy. When everyone was living together at the hippie crash pad on College Street, the men used to go to the local colleges and check girls out of their dorms for the night like library books. If our mothers didn’t know, it’s partly because they didn’t want to know.

I know the tale of a communal case of crabs that forced everyone to sit around a hotel room together with their cocks lathered, laughing, which seemed funny until it was mentioned they had gotten into this mess by “pulling a train,” a poetic way to say a single girl took on all of them.

There was Twiggs’s legendary carousel full of slides, each one a different teenage girl, naked and splayed, and his habit of passing around copies of the statutory rape laws in the different states they passed through. There were stories of girls who waited by the side of the road topless and climbed into the Winnebago ready to be the jackpot in a poker game. Blowjobs were given on the side stage, within sight of the crowd. They balled on moving motorcycles, on the hoods of cars still warm from a ride, in gas station restrooms during a quick refueling, in Rose Hill Cemetery on graves in the moonlight with other men’s wives.

I was often told that my father wasn’t the one who got up to this mischief, that he’d opt out by holding up the book he was reading, but he held his most private cards very close.

The crazy thing is, I wanted to know. Even as I felt a dark rage growing in me, I never shut down the storytellers.

I will always identify with the women, the ones at home and even the girls on the road. But I understand that the temptation for a pack of twenty-year-old rock stars was impossible to resist. If you were generating the kind of heat they were putting out onstage, it would have been impossible to go to bed and shiver alone. My question, though, is why did they marry and have babies so young? Did they need a different kind of life at home, a soft place to fall? Or did they get trapped when our mothers got pregnant? Did they really think of their families that way? Or did they just want it all? Well, they got it all, but it didn’t come cheap.