ACROSS THE WEST SCHELDT the 2nd Division, too, had completed its part in the battle.

On 24 October the 4th Brigade began its advance up the South Beveland peninsula toward Walcheren Island, 40 kilometres to the west. Like the Breskens ‘island,’ it was polder country. For the first 12 kilometres their route led up a narrow three-kilometre-wide neck which abruptly doubled in width at the Beveland Ship Canal which gives access from the Rhine to Antwerp. Beyond that it widened again to some 18 kilometres. About halfway between the Canal and the near end of the causeway to Walcheren Island, was Goes, the largest town. Simonds recognized that the ‘neck’ and the Beveland Canal were the key obstacles to be surmounted in clearing the peninsula. He decided to turn them and speed operations by landing the 5th Brigade on the southern shore, west of the Canal.

While their battalions were completing the clearance of the Woensdrecht area, the brigade staff prepared detailed plans for the landings with the 79th Armoured Division.

By the 22nd it had become obvious that the 5th would not be free of its commitments in time for the operation. Simonds decided to replace it by 156th Brigade of the 52nd Lowland Division and the 5th Brigade’s plans were handed over to them.1

At that time it was forecast that the 4th Brigade would seize the causeway onto Walcheren over which the other two brigades would cross to clear the Island.2 While amphibious attacks were being planned against the south and west coasts of the Island, they might be foiled by the uncertain weather of late October, if not by the enemy. The land route might prove to be the only entrance to the Island fortress and its capture now was vital and urgent.

Leading the 4th Brigade, the Royal Regiment of Canada soon overran the defences in the narrowest part of the neck. Brigadier Fred Cabeldu then ordered a column of tanks, armoured cars and infantry to press forward to the ship canal. Mud, mines and anti-tank guns soon put paid to that venture and the battle, as elsewhere in the polders, became one for the infantry. Real progress could only be made at night. In a series of small outflanking attacks which obviously shook the confidence of the enemy, the Brigade reached Krabbendijke by the 26th. There its weary battalions halted and the 6th Brigade took up the advance.

Early that morning the 156th Brigade of the 52nd Division began landing on two beaches near Hoedekenskerke. They had sailed from Terneuzen in 176 LVTs of 79th Armoured Division and 24 Assault Landing craft of the Royal Navy which had been brought by train from Ostend to the canal at Ghent. Leading the flotilla, as in the Breskens assault, was Lieutenant Commander Franks, the naval liaison officer at First Canadian Army Headquarters. At 4:30 a.m. artillery began firing on the landing beaches, and 20 minutes later, the leading troops touched down. On the right the 4/5 Royal Scots Fusiliers were met by some ineffective shellfire but the 6th Cameronians were unopposed.3

During the day the British expanded their bridgehead in spite of a strong counterattack from the north which made a temporary penetration. By nightfall the 6th Cameronians had taken Oudelande, the 7th Cameronians had landed and the bridgehead was securely held. That afternoon the 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade attacked toward the formidable Beveland Canal which now had been outflanked.

Each of the Brigade’s battalions was directed toward possible crossing places. In the centre the South Saskatchewan Regiment headed for the main road and rail bridges. On the right the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada had two bridges and the vital canal locks at the northern terminus as their objective, while Les Fusiliers de Mont-Royal had the equally important southern locks to capture.

During the advance the Brigade lost its dynamic commander, Brigadier Guy Gauvreau, seriously injured when his jeep struck a mine. That bullets are no respecters of rank had already been shown on the 16th when Lt-Colonel T.A. Lewis, commanding the 8th Brigade, was killed by machine-gun fire south of the Scheldt. The deputy commander of the 156th Brigade and his batman were luckier. They were the only survivors of a direct hit on their LVT.

As dawn broke on a wet and windy 27 October, the Camerons saw that all bridges over the canal had been blown and that the enemy were holding the far bank. Quick crossings were defeated by German mortar fire and when they attempted a boat crossing, eight of their nine assault boats were sunk. In the centre, after initial setbacks, the South Saskatchewans managed to scramble across broken bridges and seized a foothold which they held against two counterattacks. Eventually the Fusiliers too were successful. Wading through waist deep water at night, they reached the locks which they crossed hand-over-hand, and fell upon the rear of a surprised enemy, 120 of whom they took prisoner. By noon, a bridge had been completed on the SSR front and the 4th and 5th Brigades began advancing through the 6th.

On the right the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment worked westward along the north coast. On the 31st members of the Dutch Resistance told Major Dick Porteous, commanding the leading squadron, that there was a small German garrison on the island of North Beveland which lies some 400 metres away across a channel of the Scheldt called the Zand Kreek. Through it the enemy still kept open a line of communications to their troops on Walcheren.

That night Porteous and his squadron, with a company of heavy mortars and machine guns of the Toronto Scottish, commandeered boats and barges near a ferry station and crossed to the island. They found the German garrison concentrated in the town of Kamperland near its western end and demanded their surrender, which was refused. The Canadians responded with 4.2-inch mortar bombs.

By this time, Porteous had been joined by Lt-Colonel Mowbray Alway, his commanding officer, who called for air support. 84 Group was completely committed by this time to operations on Walcheren but agreed to direct a squadron across North Beveland in a show of strength. Alway warned the enemy that his supporting aircraft would make one pass over Kamperland without firing but that on the next they would blow them off the face of the earth.

On schedule, 18 Typhoons roared across the island at 50 feet. The sound of their engines had not faded before the first Germans were seen emerging from the town carrying a white flag. In all, over 450 prisoners surrendered to the 8th Recce on North Beveland.

By the 29th it was obvious that South Beveland would soon be clear. Two brigades of the 52nd Division were ashore and their artillery had joined them by the land route through Antwerp. The 4th Brigade had met them near Gravenpolder and was advancing to the west. The 5th had liberated Goes. The weary 2nd Division was nearing the end of its task.

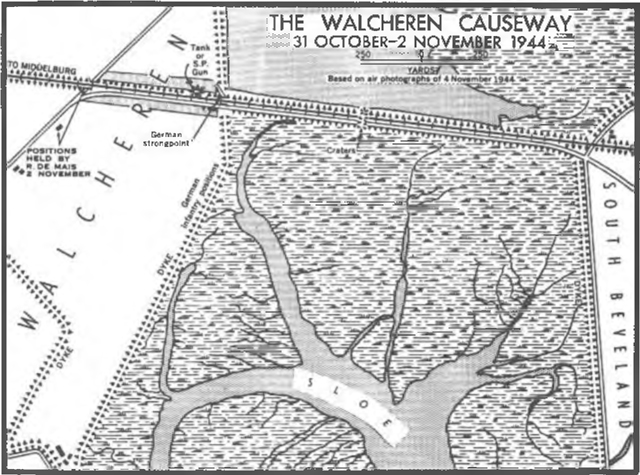

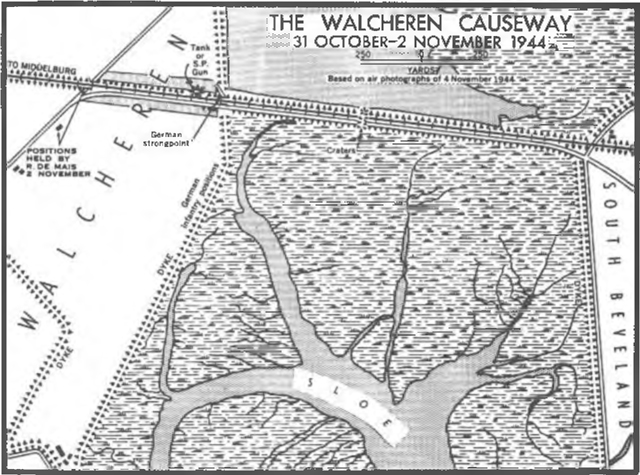

Ahead lay only the causeway which carried a road, a railway and a bicycle path and a thin line of poplars to Walcheren Island. Across it in the past few days, the retreating remnants of the German garrison of South Beveland had been withdrawing. They had fought well enough but since the crossing of the Beveland Canal, their resistance had faltered. An increasing number of prisoners were surrendering and their casualties in dead and wounded had been heavy.

Within the 2nd Division, little was known about the enemy on Walcheren. A large-scale map with an overprint issued on 23 October showed in some detail the German defences east of the Causeway but indicated none at its western end.4

Yet, if the enemy continued to retreat as he had been doing in the past few days, there was a possibility that the Causeway could be ‘bounced’ — taken by a swift, bold stroke — at little cost. And if it were, the opportunity of taking Middelburg, the island’s main town, only four kilometres distant, could not be ignored.

Late on the 30th the Royal Regiment were within 800 metres of the east end of the Causeway. They expected to take the enemy positions covering it by morning. Earlier that afternoon, Brigadier Keefler, the acting commander of the 2nd Division, asked Brigadier Cabeldu ‘to try and exploit further and push a bridgehead over the causeway to enable another brigade, possibly of the 52nd Division, to pass through.’5 At the same time he ordered Brigadier Megill of 5th Brigade to make a plan for clearing the eastern part of Walcheren Island presumably in the event that the 52nd Division was not available.6

Cabeldu did not like the idea. A glance at a large-scale map showed what a daunting task it was likely to be. Rising a few feet above sodden mud flats, the bare 40-metre-wide causeway led 1,000 metres straight across the gap from the mainland. There was not a vestige of cover on it to shield troops from the enemy guns which must surely be trained upon it. And it was mined. On either side the mud flats were bare at low tide but were hidden at high water. He reckoned that a direct assault across the causeway had a slim chance of success if it were carried out by fresh troops. Otherwise a major water crossing would be involved such as that rehearsed in England before the invasion by some units of the Division in anticipation of an assault-crossing of the Seine. It would take some time to mount, and he knew that 5th Brigade had already made plans for it. He discussed the problem with his battalion commanders who agreed with him, then drove to divisional headquarters at Goes to see Keefler. He put the case that given the tired state of his troops — and of the other brigades — an attempt to force a direct passage over the causeway had little chance of success. It would be better to try a storm-boat crossing. In the interests of speed, 5th Brigade, who had done some planning, should be given the task. The Calgary Highlanders of that brigade were one of the two units in the Division who had the necessary training.

Keefler agreed.7

Shortly after the advance onto Beveland began, the task of planning an assault across the Causeway had been shifted from the 4th to the 5th Brigade. On the 29th, the 5th Brigade’s diarist noted: ‘Our job has not changed — we are still to go on as fast as possible to secure the causeway’; words which imply taking its western end.

Few tried to hide their disappointment when their brigadier told them on the 30th, without any suggestion that it was a contingency plan, that they were not to ‘bounce’ the Causeway but to prepare to clear the unflooded part of Walcheren Island. Preliminary orders had been issued to battalions who had briefed their men when word was received that the operation was ‘off.’ The 52nd Division would clear the island. The Brigade was ordered to ‘stand down’ and it was now widely believed that they were to be withdrawn for rest. After a peaceful night they learned that Keefler had changed his mind. 5th Brigade were to secure a bridgehead on Walcheren Island for the 52nd Division.8

The changes of plans, the disappointment inflicted on weary troops and what was to follow gave rise to bitterness and rumour. It was said that Keefler had set a race for the 4th and 5th Brigades. The one which failed to reach the causeway first would have the task of assaulting across it — a cynical way to avoid a commander’s responsibility for selecting men for a hazardous mission. The official history states that he had indeed said that, but, in fact, he had selected the 5th Brigade for the task early in the advance. Later he contemplated giving the job to 4th Brigade but decided against it after Cabeldu’s representations. Nonetheless, before the operation began, officers and men of the 5th Brigade gained the impression that indecision and chance, or both, were playing an undue part in their fate.

Simmering beneath the surface, especially in the Black Watch, was a sense of outrage at the way they had been handled in the past. For them, it had begun when their rifle companies had been practically wiped out in their first major battle in Normandy and had flared up after the disaster of Operation Angus near Woensdrecht only two weeks earlier. In four months they had had more than 1,400 casualties, a rate far in excess of that of infantry battalions in the First World War. The Calgary Highlanders’ casualties were only slightly lower, while those of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve were considerably less, a reflection not of lack of aggressiveness on their part, but of a chronic shortage of reinforcements even worse than in the English-speaking regiments. Any operation about to be undertaken by troops who had been subjected to such severe strains would have to be carefully handled indeed.

So serious was the situation in the Black Watch that Bruce Ritchie, their commanding officer, appended a note to the War Diary of 31 October, 1944, describing the critical situation which had arisen from the shortage of officers, and NCOs and from the lack of training of private soldiers who came to replace their casualties. He added these chilling lines:

The morale of the Battalion at rest is good. However it must be said that ‘Battle Morale’ is definitely not good due to the fact that inadequately trained men are, of necessity, being sent into action ignorant of any idea of their own strength, and after their first mortaring, overwhelmingly convinced of the enemy’s. This feeling is no doubt increased by their ignorance of fieldcraft in its most elementary form.

On the morning of the 31st at 10 a.m. Megill broke the news to his commanding officers that the 5th Brigade was to form a bridgehead on Walcheren Island. The Black Watch would lead the attack by sending a company across the Causeway to determine whether or not a crossing by that route was feasible. The Calgary Highlanders would, in the meantime, prepare to cross the water gap by storm boats at high water, about midnight, when the tide would measure 14 feet. They would be followed by the Maisonneuve.

If the Black Watch were successful in crossing, the Brigade would follow them over the Causeway.9 Few thought that there was much likelihood of that happening. On past form, the Germans would have every inch of it covered by fire, and the gallant old militia regiment from Montreal was heading for another disaster.

While the Watch made ready for their advance to the Causeway, Major Ross Ellis of the Calgaries prepared for the storm-boat assault. Only a pitifully small number of those who had trained in England for the Seine crossing survived, there were no covered approaches to the launching sites and practically nothing was known of the German defences. Having explained his reservations to the brigade commander and being told to ‘get on with it,’ he ordered Captain Francis H. Clarke to run a ‘crash’ training programme.

I couldn’t believe the storm-boat idea. When I got the order from Ross Ellis, I presumed to say that he had to be kidding. He wasn’t. With my veteran platoon commanders, John Moffat and Walt LeFroy, and one or two NCOs, we drew boat outlines on the ground pending the arrival of the Engineers with the real thing, and proceeded with loading and off-loading drills. All the time I, and I believe others, were praying that sanity would return to someone in a position and prepared to stop it before too late.10

Close to midday, C Company of the Watch, commanded by Captain H.S. Lamb, stepped onto the Causeway as enemy shell and mortar fire burst about the approaches. As they advanced, machine guns began a cross-fire whose effect was limited by poor visibility but snipers located in the marshy flats beside the Causeway, were deadly. Beyond the halfway mark, the company found a huge crater or furrow filled with water which effectively destroyed any hope that tanks would be able to follow them. Beyond it, the leading platoon worked forward to within 75 metres of the far bank. Then all forward movement halted as a constant hail of shell, mortar and machine-gun fire drove the company to dig in. One very heavy enemy gun sought out the men on the Causeway sending plumes of water 200 feet high when its shells dropped short. At least one high-velocity gun was firing down the road from close range, ricocheting armour-piercing shells off the road, close to the much-depleted company. Later, even with darkness to shield them, it was impossible to evacuate their casualties since the slightest sound of movement drew a storm of enemy fire.11

The Black Watch had found the expected answer to the strength of the German opposition. And while they occupied the enemy’s attention, engineer officers discovered something else — even at high tide there would be insufficient water for boats to cross to Walcheren and the mud flats would not support amphibious vehicles. There was no other route forward for the 5th Brigade but the Causeway. Megill ordered the Black Watch to hold the position near the far end and the Calgary Highlanders to pass through them and establish a bridgehead. Once they had done so, the Maisonneuve would follow and expand it.12

Major Ellis’s plan was for his leading company to seize an arc about 200 metres deep around the end of the Causeway. His following companies would extend this to a depth of about 1,000 metres, each being centred on a key road junction. Supporting them would be field and medium artillery, 40mm Bofors AA guns, 4.2-inch mortars and medium machine guns. Coopting the mortar platoons of other battalions, he arranged for each of his companies to be supported by six three-inch mortars whose high angle of fire could reach an enemy close by on the far side of a dyke.13

At midnight Captain Nobby Clarke with B Company began to cross, while artillery concentrations were directed at suspected enemy positions. But they were not all covered. The Germans had moved in more close-support weapons which poured a withering fire into the advancing Highlanders. The leading platoon soon practically ceased to exist. Clarke coolly assessed the situation and asked for permission to withdraw his men to the crater in the centre of the Causeway, while a new fire support plan was made. It was granted and he and Ellis went to Megill’s tactical headquarters to explain the situation.

Ellis told the brigadier that, with a new fire plan, he reckoned that the Calgaries could establish a bridgehead but that, because their strength was so depleted, they would be unable to hold it for long. He recommended that the Maisonneuve should be sent over early to help.14

It was 6:05 a.m. when D Company of the Calgaries set out to cross the Causeway. This time the barrage extended well onto the mud flats to take care of snipers. Forty-five minutes later the leading platoon commanded by Sergeant ‘Blackie’ Laloge had inched their way to within 25 yards of a road block covered by concrete positions at the western end. There they were pinned down by machine-gun and 20mm cannon fire.

Major Bruce MacKenzie, the company commander, examined the block with distaste. There was no clever alternative to a direct assault. He announced his conclusions in pure western Canadian, ‘Shit!’15

Huddled in a shell hole with Laloge, he radioed for a two minute artillery concentration at ‘intense rate’ to pound the German positions ahead. As the last shell burst, D Company were on their feet and charging the road block. Men fell in the withering cross-fire of MG42s but speed protected others who, within seconds, were in the German position, spraying the defenders with automatic fire. Fourteen prisoners surrendered and MacKenzie’s men began fighting their way toward their objectives, unaware that they had stepped foot on Walcheren Island at almost the same moment that British commandos had landed at Flushing.

At 9:33 MacKenzie reported that his small bridgehead was secure but casualties had been heavy. Ellis ordered A and B companies to cross and move out to the north and south respectively but to be wary of the high-velocity gun which was still bouncing shells off the roadway. When both were near their objectives, enemy fire on the Causeway once more became so hot that C Company following them was forced to take cover.

Probing south from the western end of the Causeway, B Company was strung out along the bottom of the dyke which marked the edge of the tidal mud plain, their objective a group of farm buildings some 50 metres inland from it. The top of the dyke and the intervening ground were devoid of cover and raked with automatic fire. They needed mortar and artillery support to keep the enemy’s heads down. With both his radios knocked out, Nobby Clarke sent back two runners with requests for fire support but neither reached battalion headquarters.

I clearly recall my despair and exasperation at our position because we could actually see battalion observers across the flood plain on the far dyke. We prayed that they would appreciate our position and act … a ridiculous and foolish hope.16

A Company too were under such heavy fire that they could not move. A determined German counterattack nearly penetrated to the end of the Causeway but stopped and fell back before a furious Sergeant Laloge of D Company hurling grenades practically into their faces. Brigade headquarters asked Ellis when he would be clear of the Causeway so that the Maisonneuve could cross. He replied, ‘Not before 13.30.’

At 3:45 p.m. Ellis, accompanied by George Hees, the brigade major, crossed the Causeway to see the situation for himself. They returned but set out for the other side once more when they learned that Captain Win Lasher, the only officer in A Company, had been wounded for the third time. Hees volunteered to replace him and another artillery officer, Captain Bill Newman, offered to serve as his second-in-command.17

The German fire and counterattacks mounted in ferocity until there was imminent danger of A and B Companies being cut off. There was no alternative for the few who were left but to pull back behind D Company.

With communications destroyed, no orders for the withdrawal were received by Nobby Clarke:

I became aware that … ‘D’ were moving back along the Causeway toward the crater. When I went to ascertain the situation at my rear, I found Sgt Laloge swearing something fierce and returning Gerry grenades as fast as they arrived over the dyke. Unfortunately he didn’t get them all because the handle from one of them struck one of my lads and broke his leg. I put a rifle splint on it and we lowered him into a slit trench, remembering to prop him up because, with the tide, the trench would partly fill with water.

I was now in danger of being cut off. I simply had to maintain contact with ‘D’ at my rear so we began working back. You can believe me that this was the last thing I wanted to do.18

Ross Ellis now ordered A and C Companies to dig in near the cratered area and reported to Megill for orders. He was told to hold fast until instructions were obtained from divisional headquarters. Hours went by while the Highlanders waited under constant heavy fire. It was past midnight when they learned that Megill had ordered Le Régiment de Maisonneuve to pass through them on the Causeway and establish a small, tight bridgehead which 157th Brigade could exploit.19

The War Diary of the 5th Brigade on 2 November reflected one facet of the uncertain direction of the Causeway battle.

During the early hours of the morning the plan was changed by Div HQ once more. Now the R DE MAIS are to be relieved at 0500 hrs by 157 Bde, only one hour after they start their push. This will result in a one company bridgehead only. CALG HIGHRS are to pull out as soon as the R DE MAIS company have gone through in order to make way for 157 Bde’s leading battalion (Glasgow Highlanders).

… at 0400 hrs they started over. Once again they received the same type of reception as the other two battalions and had great difficulty in getting over the causeway and were held up temporarily by shell and mortar fire.

By the time Captain Camille Montpetit’s D Company had struggled onto Walcheren it had been reduced to less than 40 men. Charles Forbes, commanding the leading platoon, captured an anti-tank gun which had been firing down the Causeway and pressed on to a house which was their objective. The remnants of the company soon were fighting a confused and hair-raising battle in the dark, uncertain either of their own or the enemy’s locations. Somewhere close by, three 20mm automatic AA guns were pumping a mixture of high explosive and armour-piercing shells into the Canadian positions.

Dawn broke grey and dirty for the Maisonneuve on Walcheren and there was no sign of the British troops who were to relieve them. But there were Germans aplenty. A column of them, withdrawing toward Middelburg, came down the road toward Forbes’ position from the east. Nearby, across a dyke, Guy de Merlis watched, PIAT ready, as a tank moved toward his position. Then suddenly that menace was no more, as rockets from an RAF Typhoon lifted the turret from its hull. Then Private J.-C. Carrière took the PIAT, crawled down a ditch full of water and destroyed one of the 20mm guns which had been making life difficult for the platoon.10

At 5th Brigade Headquarters, an imperial row had blown up. The progress of the battle for the Causeway had been watched with keen interest and mounting disbelief by officers of the 52nd Division as Megill sent three battalions in succession along that road of death. Their military instincts were revolted by this violation of a cardinal principle — never to reinforce failure. They did not question the need to take a bridgehead on Walcheren and they could not at the moment suggest another way to cross. But given time, they would find one. Of one thing they were certain — there had to be a better way to fight this battle.

Major-General Edmund Hakewill-Smith, commanding the 52nd, who now was to command all the operations on Walcheren Island, had been opposed to the concept of the 5th Brigade’s frontal attack from the outset. When on 1 November, Charles Foulkes, the acting commander of the 2nd Canadian Corps, ordered him to send his men across the Causeway, he refused, saying he would find another route. In an atmosphere of mounting acrimony, the discussion ended with Foulkes threatening to sack him if the 52nd Division failed to attack within the next 48 hours.21

Brigadier J.D. Russell of 157th Brigade was already urgently looking for an alternative to the Causeway for his troops to cross, when Megill demanded that he relieve the Maisonneuve. Russell was unwilling to commit his brigade to the operation but finally agreed to send over as many men as the Maisonneuve had on the opposite side of the Causeway. It was accepted that there were no more than forty.

The history of the 52nd Division described the scene:

It was at six o’clock on the morning of November 2, 1944, that No. 10 Platoon of B Company of the Glasgow Highlanders started to lead the battalion into hell. That conventional phrase does not exaggerate the horrific situation. The Germans had … the Causeway completely taped and plastered. The smoke of continual explosions eddied always over the embankments. The noise and incessant shocks tried the stoutest of nerves. The whole of the dam, sides and surface, was pockmarked with craters. The trees were splintered parodies of green growth. To move a foot in daylight was nearly impossible; to advance a yard in the darkness was an adventurous success.22

Behind them, three companies of the regiment moved onto the Causeway to take over the Canadian positions.

When the Scots reached the Maisonneuve, the enemy fire was so intense that it was impossible for anyone to move. Two hours later, covered by a smoke screen, both pulled back to the Causeway.

During the night of 1 November, two young men, Lieutenant F. Turner, MC, and Sergeant Humphrey of 202 Field Company, Royal Engineers, embarked on one of the most dangerous and technically challenging reconnaissances imaginable. After carefully studying airphotographs, they set out to cross the Slooe channel three kilometres south of the causeway. Picking their way through the quicksand-like mudflats, where more than a hundred Germans were lost in 1940, they found a path which might be followed by infantry and returned to report to a relieved Brigadier Russell. Next night Turner, with three sappers, returned to Walcheren marking the path with tape.

In the cold hours before dawn next day, the 6th Battalion of The Cameronians picked their way across, following the tape, and were ashore on the sea-dyke before they were seen by the enemy. Their reception was typically violent. Counterattacks threatened to engulf the left flank of the bridgehead while the crossing area was heavily shelled. But the build-up of strength continued until the 5th Highland Light Infantry were ashore and able to attack. The going was not easy but next day, in a headlong assault, the HLI broke through the German ring and linked up with their comrades in the Glasgow Highlanders at the Causeway.23

What happened to them later belongs in the account of the battle of Walcheren Island.

The soldiers of the 2nd Division left South Beveland with a feeling of relief that they had seen the last of polders and of the Scheldt. They put the past behind them and gave little thought to the future, determined to make the most of a week’s rest in the outskirts of Antwerp.

They did not know, nor would they have been much interested to learn, that not enough had been done to even the odds against them at Woensdrecht and that the responsibility for that was shared by Montgomery and Eisenhower. But the battle for the Causeway was a different matter. In the words of one soldier, ‘It was a bad deal.’24 By coincidence, the 5th Brigade’s numbers who fought there were almost the same as the 600 of The Light Brigade at Balaclava. Like them they have left us a rare example of discipline and gallantry. And those who came back from that Causeway of death believe to this day that they were ordered across by the military heirs to Lords Lucan and Cardigan.