WHILE THE SCHELDT BATTLES WERE IN PROGRESS, the staff at Army Headquarters were preparing for future operations. The Army was soon to take over the entire line from south-east of Nijmegen to the sea. It would be fighting a winter campaign in snow and frost with all that that entailed in the way of tactics and training, special clothing and equipment, vehicle maintenance, accommodation and camouflage. But first its exhausted divisions would have to be brought up to strength in men and equipment and trained for the hard fighting which lay ahead.

Fortunately Canadian losses in the next three months were relatively light and infantry battalions were restored to full strength. But by this time it was apparent that the Army could not be sustained by volunteers alone. Since 1940 men had been conscripted for service in Canada and by late 1944 thousands of them, trained as infantry were guarding the country against a threat which had disappeared. It took months of persuasion before the Government in Ottawa could be convinced that the only solution to the problem of the rifle company of thirty exhausted and increasingly embittered soldiers was to send these conscripts overseas. In early 1945 they began to arrive and were accepted gladly, with no discrimination, in the ranks of First Canadian Army’s veteran battalions.

It was not only the three Canadian divisions which had been worn down. The Polish Armoured Division lacked reinforcements of any kind and was in even worse shape. The shortage of infantry in British divisions was so serious that two had been disbanded. It was a problem shared by all the Allies. Eisenhower complained in November that the American planners had miscalculated the number of infantry units needed in a balanced army, a deficiency compounded by a shortage of replacements for casualties.

On 7 November Lt-General Crerar, now restored to health, returned to his Army. A week later he was promoted to the rank of General, a rank never held before by a Canadian officer in the field. Simonds returned to the command of 2nd Corps, whilst Major-General Charles Foulkes, who had taken his place during the Scheldt operations, left to take command of 1st Corps in Italy. His replacement as commander of the 2nd Division was Major-General Bruce Matthews.

For exactly three months from the end of hostilities on Walcheren Island — 8 November to 8 February — there were no major operations on the front of First Canadian Army. The respite was put to good use and by the time its next offensive was launched, the Army was at full strength, trained and confident.

Before the Allies could advance into Germany and bring the War to an end, they would have to cross the Rhine. Lying before it, except in the south near Switzerland, lay the formidable defences of the Siegfried Line. The euphoria of the headlong advances across France and Belgium disappeared when the Allies realized the price they were going to have to pay to reach the river.

On 2 November, as the Scheldt battles were ending, Montgomery issued a directive to his army commanders which outlined some immediate tasks. The next operation to be undertaken by Second British Army was to drive the enemy to the east side of the River Meuse (as the Maas is known in Belgium and France). First Canadian Army was to prepare plans for offensive operations:

a) South-eastward from the Nijmegen area, between the Rhine and Meuse;

b) Northwards across the Neder Rijn, to secure the high ground between Arnhem and Apeldoorn with a bridgehead over the Ijssel river.

Planning began at once while the Army took up its new positions. Sir John Crocker’s 1st British Corps now held the line of the lower Maas as far east as Maren, north-east of ’s-Hertogenbosch, with, as Crerar ordered, ‘the minimum strength necessary, maintaining a reserve of mobile and armoured troops in suitable positions to deal with any enemy attempt to cross the river.’

Simonds’ 2nd Corps was to take over the Nijmegen salient from 30th British Corps on 9 November, their forward positions extending from Cuijk, opposite the Reichswald, across the ‘Arnhem island’ to Maren. The Army would then be responsible for a front of over 225 kilometres from the Rhineland forests to the tip of Walcheren. Its most vital defensive task was the protection of the Nijmegen bridge, the only crossing of the Rhine in Allied hands.

Opposite them was Army Group H, commanded by General Kurt Student, with his 15th Army’s front roughly coinciding with that of 1st British Corps, and 1st Parachute Army opposite Simonds.

Before the last shots were fired on Walcheren, 2nd Corps began moving to the Nijmegen area where it took command of two divisions already in position, the 50th (Northumbrian) and the U.S. 101st Airborne on the so-called island between the Waal and Arnhem. On the right the 2nd Division moved into the line opposite the Reichswald between Cuijk and Groesbeek. Between them and Nijmegen, the 3rd Division relieved the U.S. 82nd Airborne on the night of 12 November.

It was the first time that General Spry’s men had had direct dealing with Americans. They were intrigued by their language which was familiar but seemed non-military — torches were flashlights, petrol was gasoline. They were fascinated by their equipment, their robust ‘deuce-and-halfs’ and four-wheel drive ‘threequarters’ (2½ and ¾ ton trucks), their weapons and their rations. They liked the U.S. .30 calibre carbine but wouldn’t swap a Browning automatic rifle for a Bren. In fact, there was little that the Americans had that they envied, certainly not their rations nor their clothing. Everyone shivered in that damp November but the Americans ‘looked’ colder. As one battalion commander put it, ‘They were great guys, good soldiers who had fought well. We gained a great respect for them but their ways were not our ways.’1

Too many visitors can be a problem to a headquarters in the field. That of the 82nd Airborne had to be approached on foot along clearly marked paths because of the danger of mines. Major-General James Gavin was said to be the source of a widely spread rumour that close proximity to the fluorescent tape, which marked them, made men impotent.2

On the right of the Army’s line the two Canadian divisions each held their positions opposite the Reichswald with two brigades. After two weeks in the line, each brigade would spend one in reserve, training.

From positions on high ground both they and the Germans opposite had good observation over the open undulating ground west of the Reichswald. Much of it was strewn with the remains of gliders wrecked in the airborne assault of the previous September. Some were booby-trapped, some were used by the enemy to observe the Canadian positions, as some were used by our patrols. Both sides made strenuous efforts to control this no-man’s land. Almost every night patrols clashed as they tried to gain information or capture prisoners.

As in the First World War, the Canadians kept the enemy on edge with frequent raids. These were carefully planned and rehearsed and were supported by artillery, machine guns and mortars. Though they achieved some valuable results, they could be expensive.

On 20 December B Company of the South Saskatchewan Regiment, commanded by Major Bill Edmondson, raided enemy positions in front of Groesbeek to obtain information for a future attack. The assault was swift, efficient and lucky. One frightened prisoner was hustled to the rear — a staff car driver, who had been sent into the line as a disciplinary measure. But one platoon had mistaken its objective and had left a strong enemy post in action. Casualties mounted as Edmondson, in a wrecked barn, strained to keep contact with his platoons over a crackling radio net and extricate them under enemy machine gun and artillery fire.

At that point a sergeant, obviously upset, said to Edmondson, ‘I’ve got five wounded men in the barn. How am I going to get them back?’

Edmondson rounded on him and shook him into action by saying, ‘I don’t give a damn about your wounded. It’s your job to get them out. Mine is to get those sixty men out there back without any more of them getting hurt.’

The South Saskatchewans lost three men killed and 20 wounded and the sergeant learned an unforgettable lesson in the realities of war. As for the German staff car driver, disgruntled at the Wehrmacht for his punishment, he named every senior commander known to him and gladly shared his unique knowledge of the location of enemy units and headquarters.3

2nd Corps’ primary task was the defence of the Nijmegen bridgehead and of the bridges themselves. On the Arnhem island the 50th (Northumbrian) and 101st Airborne Divisions held soggy positions opposite an enemy equally determined to protect the Arnhem bridge. At this time the Germans were not capable of mounting a large-scale attack, but both sides patrolled aggressively.

At Nijmegen bridges for road and rail, captured intact, span the Waal, the main stream of the lower Rhine. Beside them the British had laid a third across a row of barges. Almost every day the Germans attempted to destroy them by shelling or air attacks. At the end of September enemy frogmen, using mines, blew a gap of 80 feet in the road bridge which was soon repaired, and destroyed a span of that carrying the railway. In November and December they damaged the barge bridge by floating mines down the stream.

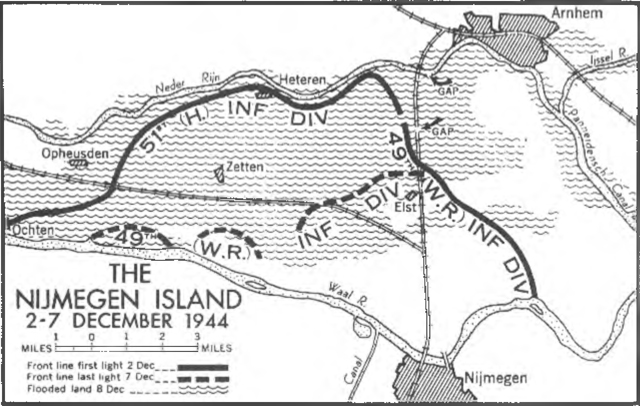

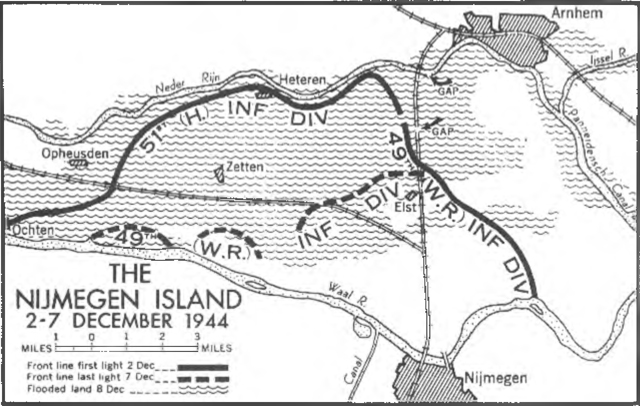

At the end of November the 49th (West Riding) and 51st (Highland) Divisions relieved the troops on the Arnhem island. A few days later the Germans blew the river dyke and the railway embankment south of Arnhem, allowing water of the lower Rhine and the Waal to flood the low-lying farm land. Within two or three days much of the island was under three feet of water. As the floods extended, the few remaining civilians and livestock were evacuated, while the British withdrew to defensible positions closer to Nijmegen. Before dawn one morning, while this movement was in progress, units of the 6th Parachute Division attacked the 49th about three miles upstream from Nijmegen. At first they made some progress but a counterattack drove back the enemy who left behind 60 dead and more than a hundred prisoners.

In January, 1945, the Germans made another attempt to destroy the Nijmegen road bridge. Late in the evening of 12 January Lt-Colonel Roger Rowley, of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, was called forward by Captain Jake Forman of C Company who mysteriously asked his C.O. not to bring his artillery representative with him. When Rowley arrived forward, Forman led him to the river where, alongside a warehouse, on the opposite bank, they made out the shapes of two midget submarines. Men appeared to be loading them. Forman explained that he was moving two anti-tank guns into position and had given them instructions that, on his order, they would open fire with armour-piercing ammunition, followed by high explosive shells. He was confident that he could sink the two boats and didn’t need any help from the artillery who would only claim the credit for it.4

When eventually the submarines moved out into the stream, the anti-tank guns ended their part in what was a much larger enterprise. Other submarines were engaged that night by the 12th and 14th Field Regiments, Royal Canadian Artillery, but the scale of the operation only became known after the War. The Germans had launched 17 midget submarines, or ‘Biber.’ None of them reached the Nijmegen bridge. Eight members of their crews were lost.5

Further west, 1st British Corps held the south bank of the lower Maas with the 4th Canadian and 1st Polish Armoured Divisions on the right and left respectively. The 12th Manitoba Dragoons patrolled the 25 miles of the Maas from its mouth opposite Schouwen to the canal just west of Moerdijk. The 52nd Lowland Division continued to occupy Walcheren.

Generally the front was ‘quiet.’ There were frequent artillery duels and 1 Corps and German patrols probed across the river.

Since early November the planning staff at Headquarters First Canadian Army had been studying the problem of an attack south-east from Nijmegen to clear the west bank of the Rhine. On 7 December Montgomery telephoned Crerar and gave him the responsibility for carrying out the operation. For it the Army would be reinforced by 30th British Corps including one armoured and four infantry divisions. The target date for ‘Veritable,’ as it was to be called, was 1 January, or as soon as possible thereafter.

By the time Montgomery issued a written instruction for the operation on 16 December, preparations were in full swing. Army and Corps staffs had completed their initial plans and the tremendous task of building roads capable of supporting the operation had begun.

On that same morning, 16 December, 1944, in poor visibility, von Rundstedt launched the 5th and 6th Panzer Armies against the thinly held American front in the Ardennes forest. Its primary aim was the encirclement and destruction of 21 Army Group. It achieved complete tactical and strategic surprise. In the days that followed, the German spearheads penetrated more than 80 kilometres. Some American units were completely overwhelmed, but others held their ground tenaciously.

The Allies regrouped and, when skies cleared, the air forces attacked the Panzers. The Germans were halted within two miles of the Meuse.

The enemy’s Ardennes offensive was to have a profound effect on Crerar’s battles in the Rhineland. In the meantime First Canadian Army was not much involved.

On 19 December 30th Corps was taken away, temporarily, to prepare to counterattack if the Germans crossed the Meuse. Two days later the Intelligence Section at Army Headquarters detected some disquieting activity on the part of the enemy north of the Maas in Holland. Four to five divisions were concentrating in preparation for an attack.

Von Rundstedt had ordered Army Group H to be prepared to cross the lower Maas once the Ardennes thrust reached the Meuse. The initial thrust would be conducted by 88th Corps whose pedestrian commander was replaced by Lt-General Felix Schwalbe, a man more suitable for a difficult and dashing operation. His force of two infantry and two parachute divisions would be supported by 150 tanks.

Crerar regrouped 1st British Corps on whose front the attack would fall and positioned divisions ready to counterattack. All administrative units were ordered to prepare for their own defence while continuing their preparations for ‘Veritable.’

Between Headquarters First Canadian Army in Tilburg and the Maas, 18 kilometres to the north, stood one platoon of infantry and an armoured car troop. For the first time it looked as if the staff might have to defend themselves. Officers, clerks, drivers, cooks and signallers drew extra ammunition and grenades, dug slit trenches and manned guard posts. The Armoured Corps section crewed two armoured cars, the artillery some anti-tank guns. All were told of the alarm signal — a Bofors AA gun firing bursts of four rounds across the town.

About 10 o’clock one night, just such a series of bursts was fired. For a time all was silence then suddenly came the unmistakable sound of a Bren from the direction of the nearby Ordnance Field Park. More machine guns opened up.

Inside a school which housed some of the staff, an officer found his young clerk shaking, speechless and near to tears. A sergeant explained that the boy had been on duty as a sentry on a vehicle park and had shot an Army Service Corps officer who had failed to halt when challenged. Fortunately he had just winged him and it was questionable which of them was in worse shape. After half an hour an officer of the Defence Battalion arrived and reported that it had been a false alarm.

Later they discovered what had happened. Two Dutch civilians selected that night to rob the Ordnance Field Park. Armed to the teeth with machine guns taken from stores, the Ordnance unit had never been so alert or so well guarded. When a sentry saw two figures crawling under the wire of the boundary, he opened up with his Bren along the line of the fence. With bullets cracking over their heads, the next post beyond the intruders believed themselves to be under attack and fired back. Others eagerly joined in. Soon a full-scale fire fight developed.

Apart from the two Dutchmen, no one was hurt, but the officer commanding the Field Park noted that there was a marked decrease in pilfering after that.6

With the end of the German offensive in the Ardennes, 30th Corps returned to First Canadian Army. Preparations for ‘Veritable’ which had been continuing, now took top priority. Even before operational plans were finalized, a tremendous amount of work had been done.

In early February the ground was likely to be snow-covered — tons of white sheeting, camouflage suits and paint were distributed. To concentrate some fifteen divisions with thousands of tracked vehicles, guns and a vast quantity of wheeled transport would be far too much for country roads. New ones were built and the others reinforced. Thousands of tons of ammunition, of POL (petrol, oil and lubricants), of engineers’ stores and rations were brought forward and concealed in readiness.

One painful result of the Ardennes offensive was the battle of Kapelsche Veer. There the Germans held an outpost on an island which lies in the river Maas, north of Tilburg. Army Group H had named it as one of the crossing places for their projected attack across the river. On 21 December its garrison was increased to one company, plus an advanced observation post supported by medium artillery, self-propelled guns and mortars from north of the Maas.

Both Crocker and Crerar were very concerned at the condition of the Polish Armoured Division. Its ranks now were filled by ill-trained men who only a few months before had been serving under compulsion in the German Army. Ideally the Division should be taken out of the line for reorganization and training but this was not possible. By the end of December the likelihood of a major German offensive from across the river had faded. Yet it would have been foolish to leave such an active enemy bridgehead on the front of such a weakened formation.

On the night of 30 December Polish infantry attacked. They made little progress against a well dug-in enemy, supported by effective artillery. After suffering 46 casualties, the Poles were withdrawn, taking with them a few prisoners from the 6th Parachute Division. A week later, the 9th Polish Infantry Battalion attacked again. By noon they had cleared the harbour area but could make no progress against the paratroops dug-in on the nearby dykes. After a fierce enemy counterattack and a loss of 120 men killed and wounded they were ordered to withdraw.

Crocker judged that the Poles could do no more and called on 47 Commando Royal Marines to eliminate the bridgehead. On the night of 13/14 January the Marines, attacking from both flanks over the open polder country, made little progress. With a high proportion of their officers casualties and ammunition nearly exhausted, they were ordered to break off the attack.

The struggle for Kapelsche Veer now assumed an importance far beyond the value of the ground or the threat posed by the German bridgehead. To abandon the fight after three failures would be to concede superiority to the enemy, an example to the shaken Polish Division which could not be afforded. Crocker ordered the 4th Canadian Armoured Division to destroy the German position.

On the morning of 26 January the Lincoln and Welland Regiment, supported by almost every gun in 1st British Corps, launched a pincer attack on the German paratroops. The enemy held their fire until the Canadians were virtually on their objective, then opened up so effectively that within minutes all the officers of the two companies attacking from the east were hit. After a fierce German counterattack, they were withdrawn from the island. On the west, despite all its platoon commanders being killed, the leading company gained a foothold, beat off enemy counterattacks and held its position until it was reinforced. By nightfall, on the opposite flank, the battalion’s antitank platoon had fought their way onto the island and there were relieved by a company of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, supported by two tanks of the South Alberta Regiment.

The island was as featureless as the polder country of the Scheldt. The only practical line of advance was along a high dyke, 300 metres in from the edge of the river. A few Shermans crossed to the island by raft or a rickety bridge, but the sodden tracks were virtually impassable for armour.

From east and west the Argylls and Lincoln and Wellands worked toward the German positions, digging in after each short move. For four more days of acute cold and misery, they clawed their way forward while the artillery pounded the stubborn German paratroops. The 15th Field Regiment fired more than 14,000 twenty-five pounder rounds during the operation.

Early on the morning of the 31st the two Canadian battalions met in the ruins of the hamlet. They had captured 34 prisoners and counted 145 German dead on the battlefield. In the final action, the Canadians suffered 234 casualties, of whom 65, including nine officers, were killed. After the War the commander of the 6th German Parachute Division said that the defence of Kapelsche Veer had cost him between 300 and 400 ‘serious casualties,’ plus 100 more men disabled by frostbite.

In all, nearly 1,000 men of both sides were killed, wounded or went missing in the snows of Kapelsche Veer.