The Old Fashioned Whiskey Cocktail—the Old Fashioned, for short1 (and sometimes referred to as the Stubby Collins)2—is a classic American cocktail.3 Although some say it is an adaptation from another cocktail—perhaps the Whiskey Cobbler or the Whiskey Cocktail4—others argue that it is the original cocktail.5 The Old Fashioned has been described as “a truly magnificent cocktail,”6 “the only cocktail really to rival the martini,”7 and “one of the immortals: strong, square-jawed, with just enough civilization to keep you from hollerin’ like a mountain-jack.”8 That’s not bad for a drink that most sources say originated in the Bluegrass State.9

The Old Fashioned also led to other adaptations, such as the Mint Julep. Some older recipes for the Old Fashioned called for a sprig of mint and were described as “Juleps made the Old Fashioned Way.”10 According to the authors of The Official Harvard Student Agencies Bartending Course, the only two ingredients distinguishing the Old Fashioned and the Mint Julep are the bitters in the Old Fashioned and the garnishes in the two drinks: orange slice, cherry, and lemon twist for the Old Fashioned, and sprig of mint for the Julep.11

Traditionally, a cocktail always includes bitters, which separates it from a julep or a toddy. The cocktail has the added distinction of being the original morning drink,12 like a glass of orange juice or a cup of coffee today. In contrast, a julep is a sweetened alcoholic beverage that usually features mint and is consumed at midday (meaning any time from breakfast to dinner), and a toddy is a sweetened alcoholic beverage that can be served hot at the end of the day.

Ted Haigh (aka Dr. Cocktail) observes that the Old Fashioned eventually evolved into an “ugly slurry that has nothing to do with the original drink,”13 which Brad Thomas Parsons (author of Bitters) refers to as “the fruit salad” approach.14 The modern drink is actually a return to the historical version: a simple mixture of a little sugar, a little water (or simple syrup in their place), bitters, whiskey, and a slice of orange or lemon peel—a recipe that delights palates all over the world. The early versions differ from what most people think of as an Old Fashioned in that they lack fruit. The limited number of ingredients, the simplicity of the recipe, and the need to make the low-quality whiskey of the past palatable suggest that the Old Fashioned predates other cocktails.

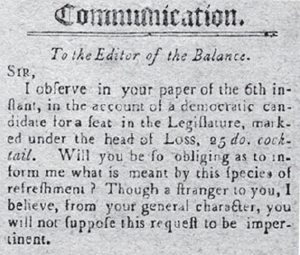

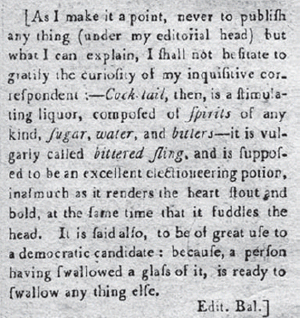

The Old Fashioned is now on the beverage menu of most bars that serve cocktails, and no cocktail book is complete without at least one recipe for the Old Fashioned. But at what point did this cocktail become “old-fashioned” as opposed to a new concoction, which it must have been at some point? As with most great things, there is myth and there is truth. Part of the lore is that the term cocktail dates to 1776 in Elmsford, New York, where the owner of a bar ran out of wooden stirrers and substituted cocks’ tail feathers. During that time, cocktails were also known as “roosters.” In 1806, in response to a reader’s question, a newspaper editor at The Balance and Columbian Repository in Hudson, New York, defined a cocktail as “a stimulating liquor, composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water, and bitters” (note that ice is not mentioned).15 (Both the reader’s query and the editor’s reply are reproduced here.)

To put the timing of this definition in perspective, Thomas Jefferson was the president of the United States, George III was the king of Great Britain, and Napoleon I was the emperor of France. The original cocktail most likely included a domestic whiskey (rye grain was—and still is—grown in New York State and distilled into rye whiskey), as most other “stimulating liquor” would have been imported. The United States’ largest trading partner in 1806 was Great Britain, which was trying to limit U.S. trade with France, eventually leading to the War of 1812. Because of this conflict, the United States relied as much as it could on domestically produced products, including whiskey. In addition, any imported liquor would have been much more expensive because of the import tax levied. At the time, import taxes were the U.S. government’s only source of revenue; items produced in the United States were not taxed, and the permanent income tax did not take effect until after 1913, with passage of the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

In short, in all likelihood, the first cocktail was made in New York State with rye whiskey, bitters, sugar, and water and garnished with the tail feather of a rooster. The whiskey was of strong proof, as evidenced by the last two sentences of the newspaper editor’s answer: a cocktail “is vulgarly called bitter sling, and is supposed to be an excellent electioneering potion, inasmuch as it renders the heart stout and bold, at the same time that it fuddles the head. It is said also, to be of great use to a democratic candidate: because, a person having swallowed a glass of it, is ready to swallow any thing else.” In other words, the drink was so strong that it impaired the judgment of the person consuming it. The “democratic candidate” mentioned by the editor refers to the Democratic-Republican Party of Thomas Jefferson, which opposed the Federalist Party of Alexander Hamilton and John Adams. Jefferson opposed the tax on wine and considered that beverage infinitely preferable to whiskey:

I rejoice as a moralist at the prospect of a reduction of the duties on wine, by our national legislature. It is an error to view a tax on that liquor as merely a tax on the rich. It is a prohibition of its use to the middling class of our citizens, and a condemnation of them to the poison of whiskey, which is desolating their houses. No nation is drunken where wine is cheap; and none sober, where the dearness of wine substitutes ardent spirits as the common beverage. It is, in truth, the only antidote to the bane of whiskey. Fix but the duty at the rate of other merchandise, and we can drink wine here as cheap as grog; and who will not prefer it? Its extended use will carry health and comfort to a much enlarged circle. Everyone in easy circumstances (as the bulk of our citizens are) will prefer it to the poison to which they are now driven by their government. And the treasury itself will find that a penny apiece from a dozen is more than a groat from a single one. This reformation, however, will require time.16

Because whiskey was cheap and wine was expensive (as it was imported and thus taxed), whiskey had become the drink of the masses. And if the whiskey of the time had a harsh taste, some bitters, a little sugar, and water would go a long way toward making it palatable. This was even more important because ice—considered a luxury item and reserved for general refrigeration—would not have been wasted on a cocktail.

Before 1792, whiskey was commonly used as currency in the United States by farmers. Whereas it would have been almost impossible for them to move a large crop to market—requiring a team of horses and a very large cart—the same crop distilled into whiskey required only one donkey to get it to market. In addition, farmers could use the whiskey they produced to purchase most of their necessities. The other option after 1775 was to trade with “pounds” issued by each individual state and denominated in Spanish dollars. Each state’s currency (also known as continental currency) traded at a different rate, which meant that one state’s currency might be stronger than another’s. For example, early in this period, the currency of Georgia was worth more than six times that of South Carolina. In addition, whenever people traveled from one state to another, they would have to exchange their currency. Whiskey provided a strong, consistent currency and allowed exchange-free passage from state to state. The Coinage Act of 1792 established a formal currency for the United States, but for years after its passage, farmers still bartered their whiskey, as they always had. Many found that whiskey was a stronger “currency” than the early U.S. dollar. In fact, when Abraham Lincoln’s family moved from Kentucky to Indiana in the early 1800s, his father, Thomas Lincoln, paid for the Indiana property in part in whiskey.

After the Revolutionary War, the United States found itself saddled with a huge war debt. In an attempt to raise funds to pay off the debt, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton suggested that Congress pass a tax on whiskey. The so-called Whiskey Act, which became law in 1791, imposed the first tax by the U.S. government on a domestically produced product. It provided two ways for whiskey producers to pay the tax: a flat fee or by the gallon. The more whiskey a producer made, the less he paid per gallon. Some small distillers claimed this tax was designed to put them out of business in favor of large distillers. In addition, it acted as an income tax on farmers who were trying to move their crops to market without incurring the expense required to transport undistilled crops.

For the first eighteen months, the tax was largely uncollected. When the government moved to enforce the law, the farmers rebelled by tarring and feathering tax collectors. This became known as the Whiskey Rebellion. In July 1794 the conflict came to a climax when shots were exchanged at the Battle of Bower Hill. President George Washington, as the commander in chief, led 15,000 militia to put down the rebels, meeting minimal resistance. Several people were tried for treason, but none were put to death. (Washington is one of only two commanders in chief to lead an army into battle. The other was James Madison, who in 1814 led troops on a retreat from Washington, D.C., when the British burned the Capitol and the White House during the War of 1812.) The Whiskey Act was repealed in 1801, during the Jefferson administration and shortly before the cocktail was first mentioned in print. While whiskey was important as a currency up to 1792, it took on new significance upon repeal as a drink that could be produced and sold tax free, unlike wine.

According to legend, the Old Fashioned was invented at the Pendennis Club in Louisville, Kentucky. Most people still believe this, and most of the literature reflects this perception. However, David Wondrich has busted this myth, pointing out that the drink was clearly mentioned in the Chicago Tribune a year before the Pendennis Club was founded in 1881.17 I would argue that the Old Fashioned as we know it today (made with bourbon and muddled fruit) might have originated at the Pendennis Club. Regardless, the members of this private club in downtown Louisville have proudly adopted the Old Fashioned and given it a home.

When a member of the Pendennis Club asks for an Old Fashioned, the expectation is that the cocktail will be made with a seven-year-old bourbon whiskey. Although the original cocktail was made with rye whiskey, by the time this drink was ordered at the Pendennis Club, it was more than seventy-five years old—or “old-fashioned.” The Kentucky bartender would have had greater access to bourbon and most likely substituted that for rye. This substitution created a new cocktail called the Old Fashioned.

Some of the first recipes, though similar, look different from the recipes of today. In 1885 La Cuisine Creole by Lafcadio Hearn featured several whiskey cocktails—including a New Orleans–style cocktail and a “spoon” cocktail—that contain all the components of an Old Fashioned except the cherry and the orange slice.18 The difference between Hearn’s two recipes is that the New Orleans–style cocktail is strained into a cocktail glass and has a choice of three bitters (Boker’s, Angostura, or Peychaud), while the spoon cocktail demands Angostura bitters and is served “in small bar glass with spoon.”19 (After almost 110 years, we have advanced from a cock’s feather to a proper spoon.) By 1895, this recipe appeared in the book Modern American Drinks by George J. Kappeler; although it is identical to the whiskey cocktail featured a decade earlier in La Cuisine Creole, it now sports the name Old Fashioned Whiskey Cocktail.20 This simple drink bears little resemblance to the modern Old Fashioned, which has a slice of orange and a cherry. Kappeler confirms Angostura bitters as the type to use for an authentic Old Fashioned and goes a step further, making the distinction between the Old Fashioned Whiskey Cocktail and the Whiskey Cocktail. The latter introduces the cherry (not part of the original Old Fashioned), uses gum syrup (rather than sugar and water), and calls for more ice; there is no mention of leaving a spoon in the glass. Thus, it is safe to say at this point that the Whiskey Cocktail can use any bitters, while the Old Fashioned must contain Angostura bitters.

The Whiskey Cocktail listed in Jerry Thomas’s Bar-Tender’s Guide, published in 1887, is similar to Kappeler’s. Thomas employs gum syrup and Boker’s bitters to create his Whiskey Cocktail. Thomas also lists an “Improved Whiskey Cocktail” that calls for “bourbon or rye whiskey” and gives the reader the choice of “Boker’s or Angostura Bitters,” suggesting that bourbon (or rye) and Angostura bitters are upgrades from the well or house brands.21 Haigh (Dr. Cocktail) draws the distinction between the two drinks in his book Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails: the Whiskey Cocktail may have curaçao added, most certainly has rye whiskey as its base, and is not garnished, while the Old Fashioned has no curaçao, uses bourbon or rye as its base, and is garnished with “a lone broad swathe of orange peel ONLY, muddled to express the orange oil.”22

The Old Fashioned Whiskey Cocktail should be served in a specific glass called, appropriately, the Old Fashioned glass (also known as a “rocks glass”). Not all cocktails have such a distinction; in fact, the Old Fashioned is one of the few. The Old Fashioned glass is perfect for any spirits or other alcoholic beverages served “on the rocks,” or with ice.23 It is also good for all sorts of mixed drinks, from Screwdrivers to Margaritas.24 The Old Fashioned glass is round, short, and squat, with a thick bottom and an opening wide enough to allow one to enjoy the aroma of anything poured into it. The glass holds between 6 and 10 ounces.25 There is also a double Old Fashioned glass that holds up to 12 ounces and is known for its heft.26

The Old Fashioned glass provides enough space to manipulate, crush, or stir the ingredients, and the bottom of the glass is built to withstand the force of muddling fruit, sugar, and bitters. There is enough room for a generous portion of liquid, ice, and fruit, and some bartenders finish the cocktail with soda water to make the glass look full.

In their book The Bar: A Spirited Guide to Cocktail Alchemy, Olivier Said and James Mellgren list the Old Fashioned glass as one of three pieces of “primary bar glassware” needed by the home mixologist; the other two are the Martini glass and the Highball or Collins glass. They note that the Old Fashioned glass is the best choice for serving spirits on the rocks.27

Originally, sugar was added to the Old Fashioned Whiskey Cocktail to make the drink palatable. In the early days of distilling in the United States, the alcohol produced was intoxicating but not very tasty. In addition, the whiskey was very high proof. The sugar sweetened the flavor of the “hot” alcohol, cooling it for consumption. Today’s whiskey is of the highest quality, so the sugar is now used to enhance the flavor of the whiskey. Water is added for no other reason than to dissolve the sugar. The finer the sugar, the more easily it dissolves; for this reason, the bartender or home drink maker should consider using castor sugar or superfine sugar. The authentic Old Fashioned calls for a sugar cube or sugar loaf, both of which require muddling to break up the sugar and allow it to dissolve into the drink.

David A. Embury, author of The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks, states that the only way to make a perfect Old Fashioned is to use simple syrup. He claims that water has no place in a cocktail and that it takes about twenty minutes to dissolve the sugar properly and completely, compared with only two minutes when using simple syrup.28 Simple syrup—sometimes referred to as gum syrup—is easy to make and consists of equal portions of sugar and water boiled for at least three minutes to stabilize the solution in liquid form. Bartenders might also substitute other liquid sweeteners such as honey, maple syrup, agave syrup, or some other flavored syrup.29

Bitters are an infused, aromatic, distilled spirit (or glycerin) containing bittering compounds such as herbs, spices, roots, barks, flowers, peels, or seeds.30 Some are based on fruits, such as oranges, but they can also be made from rhubarb, saffron, sweet rush, and grapefruit. Bitters were originally produced to relax and sooth the stomach, which is why they are sometimes referred to as “digestives.” Angostura bitters are required to create an authentic Old Fashioned. Dr. Johann Gottlieb Benjamin Siegert created Angostura bitters in 1824, after almost four years of experimentation. Siegert was a German expatriate in Venezuela when Simón Bolívar appointed him surgeon general for the military hospital in the town of Angostura. Siegert used his bitters as a natural remedy for Bolívar’s forces, and in 1830 he started to promote his special blend for sale internationally. By the time of his death in 1870, he had established the reputation of Angostura bitters.

Many bartenders used to make their own bitters utilizing a variety of ingredients. While many bitters recipes are proprietary and are kept under lock and key, several examples can be found in pre-Prohibition cocktail books. Thomas lists this recipe for “Decanter Bitters” in his 1887 Bar-Tender’s Guide:31

¼ pound of raisins

2 ounces of cinnamon

1 ounce of snake root

1 lemon and 1 orange cut in slices

1 ounce of cloves

1 ounce of all-spice

Fill decanter with Santa Cruz rum.

As fast as the bitters is used fill up again with rum.

Parsons gives advice and lists thirteen recipes for making homemade bitters.32

Whiskey is the featured ingredient in the Old Fashioned, but not all whiskeys are made in the same manner with the same ingredients, nor do they all taste the same. In fact, producers don’t even agree on the proper spelling of the word. In this book, I use the spelling whiskey throughout, except when referring to Scotch or Canadian whisky (although I concede that some bourbons are spelled whisky, such as Maker’s Mark bourbon whisky). Recipes include different whiskeys based on availability or the author’s personal preference. An Old Fashioned can be made with other distilled spirits such as brandy,33 rum,34 gin,35 or tequila,36 but most recipes feature whiskey. Some people have suggested that a “classic” Old Fashioned is made with blended Canadian whisky.37 However, this seems to oppose logic, given the type of whiskey that was produced and available in the United States around the time the cocktail was created (unless a bartender referenced an old text that called for “rye whiskey” and misunderstood that to mean Canadian whisky). As for the Old Fashioned first made at the Pendennis Club, why would someone from Louisville, Kentucky, use an imported whisky (from another state or another country) to make a cocktail when there was so much bourbon available? In New York, why would someone use a taxed, imported whiskey when tax-free whiskey was available?

To create a traditional Old Fashioned, one might use bourbon whiskey, Tennessee whiskey, Canadian whisky, Irish whiskey, Scotch whisky, rye whiskey, grain whiskey, or corn whiskey. One might also consider Japanese whiskey or Indian whiskey for a twist on tradition. How do all these whiskeys differ?

BOURBON WHISKEY is a product of the United States. It is made from a minimum of 51 percent corn mash that is usually mixed with barley malt and either wheat or rye. Bourbon comes off the still at no more than 160 proof (80 percent alcohol by volume) and is cut with pure water, which is the only thing added to bourbon. The whiskey is placed in a new charred white oak barrel at no more than 125 proof (62.5 percent alcohol by volume), where it is aged. The addition of wheat or rye influences the overall flavor of the whiskey.

TENNESSEE WHISKEY is similar in formula to bourbon, but it must be made in the state of Tennessee and must include the Lincoln County process, which involves filtration through sugar maple charcoal. This gives Tennessee whiskey a unique flavor.

CANADIAN WHISKY is made from a neutral-grain spirit and rye whiskey (which might be why some people confuse Canadian whisky for rye whiskey and believe that Canadian whisky should be used to create an “authentic” Old Fashioned). Canadian whisky can be blended with other ingredients (constituting a little over 9 percent), such as sherry wine, fruit, or other whiskeys (some are blended with bourbon). Canadian whisky must be matured for three years and can be aged in used barrels.

IRISH WHISKEY is traditionally triple distilled and can be made from corn; however, if it is termed “pure pot still whiskey,” it is made from both malted and raw barley. Triple distillation makes the resulting whiskey very smooth. Irish whiskey must be distilled in Ireland and matured for a minimum of three years.

SCOTCH WHISKY is made with malted barley and water in Scotland, distilled to a proof no higher than 189.6 (94.6 percent alcohol by volume), and aged in oak casks for at least three years. Also, the only thing that can be added to Scotch besides water is caramel coloring. Scotch whisky cannot be bottled at less than 80 proof (40 percent alcohol by volume).

RYE WHISKEY is made from not less than 51 percent rye grain and is aged in new charred oak barrels. To be labeled “straight rye,” the whiskey must be aged for at least two years in barrels.

GRAIN WHISKEY is made from any grain or mixture of grains and is generally distilled in a continuous still.

CORN WHISKEY is made from a minimum of 80 percent corn and is less than 80 percent alcohol by volume (160 proof). This whiskey can be aged in used barrels, with no minimum maturation period specified.

JAPANESE WHISKEY is a mixture of malt and grain spirits made in Japan and based on a Scottish model. Like many other aspects of Japanese life and culture, the whiskey is made to exacting standards.

INDIAN WHISKEY is one of the remnants of the British Empire, but what qualifies as whiskey in India might not qualify as whiskey anywhere else. The Indians use buckwheat, rice, millet, or molasses, and according to Indian law, the whiskey does not need to be aged. Some whiskey produced in India does qualify to be labeled as whiskey in other countries.

Traditionally, the garnish for the Old Fashioned Whiskey Cocktail is a slice of orange or lemon peel that is twisted above the glass before being placed in the drink. Over time, the citrus peel twist became an actual slice of orange (or, in some cases, both an orange slice and a lemon slice); the fruit is sometimes muddled in the drink, but it may be used just to garnish the rim of the glass. A maraschino cherry also garnishes this drink.

One of the debates surrounding the Old Fashioned is whether the fruit should be muddled. Robert Hess, in The Essential Bartender’s Pocket Guide, claims that muddling the fruit is a “fairly new addition to the drink” and warns that it “quite likely marks the beginning of the downfall” of the Old Fashioned.38 In fact, most of the early recipes don’t call for fruit at all—just a slice of lemon peel. Even the recipe used by the Waldorf=Astoria just after Prohibition calls for lemon peel.

David Embury, however, says that muddling makes the fruit flavors and liquors blend “exquisitely.”39 Jack Bettridge, writing in Wine Spectator, divides the Old Fashioned into the old (classic) Old Fashioned and the new Old Fashioned (the way people really drink it), based on muddling.40 Professional bartenders or mixologists should ask their customers if they want the fruit muddled; at the very least, the menu should describe the customers’ options. At home, you can make this cocktail however you like.

The Old Fashioned was originally consumed in the morning, as were other cocktails. The cocktail may have served the function of dealing with a hangover, providing a little “hair of the dog.” The idea is that when you wake up in the morning with a hangover, you drink a little of whatever you were drinking the night before to relieve the discomfort. Even if the Old Fashioned was not specifically designed to treat a hangover, its creator included everything needed to do so: the whiskey helps take the edge off, the sugar helps raise blood-sugar levels, the bitters settle the stomach, and the citrus peel adds a pleasant aroma.