2. YORKSHIRE’S WOOLLEN PUBS

Ask any Yorkshire football fan where the Blades and the Minstermen play. Without hesitation the answer will be Sheffield and York: it is all a question of identity and loyalty.

So much of Yorkshire’s social and industrial history has been bound up with wool that it came to represent a way of life. From the grazing of sheep for the fleece and the early cottage industry in hilltop villages to the huge mills in the river valleys and faraway markets, whole communities came to depend on wool. Identity and loyalty in the community and in ‘their’ pub became just as important as that of football supporters in the twenty-first century.

A day may come when some of the processes and jobs in the woollen industry are nothing but history. Future generations are likely to be totally baffled by cropping, for example, and wonder why the Croppers Arms was given its name.

Such is the importance of the woollen pubs that examples have been collected together and follow here, along with other buildings of woollen interest.

One of Yorkshire’s most interesting and important woollen buildings is Halifax’s Piece Hall. It was built in 1775 by Thomas Bradley to serve as a cloth market. It has over 300 rooms on the various levels where the cottage weavers from the surrounding district sold their handiwork. It now houses an openair market; in the colonnades are shops, a café, an art gallery and Halifax Tourist Information Centre.

BARKISLAND: The Fleece

Ripponden Old Bank: A58 Sowerby Bridge to Rochdale road. At Ripponden turn left on B6113 over bridge.

Taking merchandise to market has always been important, often difficult and dangerous. Ripponden Old Bank, both long and steep, is one of the most formidable routes that pack-horse teams carrying woven cloth had to negotiate. It’s no surprise then, to find a pub on the hill where the teams could stop for rest and refreshment before continuing south. It must have been with great relief that they paused at the Fleece.

Way below is Ripponden in the Ryburn valley and further distant is the Calder valley. Fine views are to be seen from the garden at the rear of the Fleece, although perhaps less appreciated by packhorse teams than by today’s motorists or walkers. A few cottages face the pub across the road.

Although the date over the door is 1737, that just records when the pub was rebuilt following the seventeenth-century destruction by fire of an older building on the site. During its life the Fleece has been a farm and has accommodated an early friendly society; in every way it has been a typical country inn, developing to meet the needs of succeeding generations. When the Pennine turnpikes came into use, and the days of the packhorse were done, the Fleece became a coaching inn and served wheeled traffic.

Today’s facilities were not available for eighteenth-century coach passengers, but with the M62 not far away the Fleece now offers a quiet and comfortable overnight stay with en-suite bedroom accommodation. Two connecting ground-floor rooms at front and back have bar service and beamed ceilings; first-floor seating is available as well as ‘snug’ table and chair space.

When they light one of the fires at the Fleece it is time to back off by several yards – a practical illustration of the pub’s warm welcome.

The Fleece at Barkisland.

The property was rebuilt in 1737 after the much older original building was destroyed in a fire. It had a variety of uses before it became a pub.

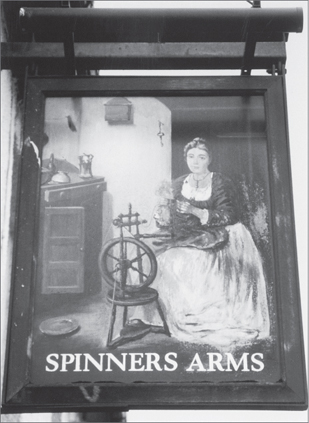

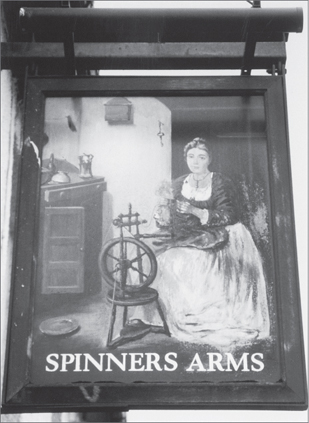

CHICKENLEY: Spinners Arms

Chickenley: M1 J40, then A638 Wakefield–Dewsbury Road.

One of the most unexpected features of the ‘woollen’ pubs in Yorkshire is that there are now so few. The industry has declined, of course, and with that decline has come a severe fall in employment in textiles. There may be little point any longer in names such as the Spinners Arms, or the Weavers, when no mills exist any more in their neighbourhoods. Certainly many pubs have changed their names, and closures have been all too common.

An example of a pub that disappeared was reported in the national press recently under the banner heading ‘The historic pub lost by the Town Hall’. It seems that the White Lion in Stafford was taken down stone by stone in 1978 to allow for the building of a ring road. Put into storage pending a rebuild elsewhere, all the stones and timber have vanished. The local authority don’t know where it is and would be grateful for any leads that would help to find it. Yet another example of the various explanations for vanishing pubs!

Chickenley’s Spinners Arms is one of the few left with that name, and possibly it will soon be the sole survivor in the West Yorkshire woollen district. As part of Dewsbury, famous for its blankets and ‘shoddy’, Chickenley would have had many spinners living and working nearby. Originally a beer house, the Spinners in Chickenley Heath stands on the busy Wakefield road formerly lined with workers’ terrace houses, now cleared. As the only building with bay windows, the pub is prominent in photographs from between the wars, especially with its signs at first-floor level.

Early records are sparse, but the Spinners Arms was in business in 1853. By 1869 it was owned by Bentley’s Yorkshire Breweries Ltd of Woodlesford, Leeds. Village loyalty was particularly strong in the days when people had to make their own entertainment and the local pub was the place where most activities were based. The Spinners Arms had its own rugby football team, now sadly gone. Local rivalries must have produced other competitive activities such as darts, but only very long memories would be able to recall life at the Spinners.

The Spinners Arms, Chickenley.

HIGHTOWN, LIVERSEDGE: Shears Inn

Shears, Hightown, Liversedge: M1 J40, A638 to Dewsbury. Turn right under railway arch. A 638 to Heckmondwike. Turn left A649 Hightown, Liversedge.

Framed on the wall in the most prominent position in the bar of the Shears is The Hartshead Ballad. The first two verses run:

Perhaps a lament would be a better title for the story of the tragic events that had their focus in this rather ordinary pub in 1812. The local shearmen or croppers used to meet in a clubroom over the front rooms on Saturday evenings, and it is their story that is enshrined at the Shears.

They were cloth finishers in the woollen industry using traditional methods to give a smooth finish to cloth, only to be threatened by the introduction of labour-saving machinery, principally Harmar’s cropping frame at the end of the eighteenth century. Two local factory owners brought in the new cropping or shearing frame: William Horsfall at his Ottiwells Mill and William Cartwright of Rawfolds Mill at Liversedge.

Since the frame, tended by one workman, could do the work of ten hand croppers, the desperation of the men of the Spen valley facing the sack and starvation can well be imagined. It would be easy to understand how they were influenced by the so-called Luddites from Huddersfield and elsewhere into using violence. Encouraged by the success of attacks on mills elsewhere, croppers from Birstall, Cleckheaton, Gomersal and Heckmondwike formed a secret society based at the Shears. The landlord, while being well aware of the croppers’ meetings, knew nothing of the conspiracy.

The first successful action by the croppers was an attack on a convoy bringing cropping frames over Hartshead Moor for William Cartwright. They then decided to attack Rawfolds Mill, but Cartwright had prepared his defence, including members of the Cumberland militia. Met with gunfire and unable to break in, the Luddites had to withdraw with several wounded. Two were left dying. Their story is continued on page 150.

The Shears Inn, Hightown.

After the murder of William Horsfall the Luddite conspirators were rounded up, and sixty-six were tried at York for the three acts of violence: eighteen were hanged.

In an alcove near the Hartshead Ballad is a collection of items associated with the Luddite events: a pair of traditional shears and photographs of a shearing frame and of Enoch. Enoch Taylor of Marsden made cropping or shearing frames and Enoch was the name given to the great sledgehammer used to smash machinery: ‘Enoch made them and Enoch shall break them’.

Also on display are the coats of arms of the Fitzwilliams and the Radcliffes. The Lord Fitzwilliam was Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding in 1798 and under his command the army was used to crush the Luddites. Joseph Radcliffe was appointed magistrate for Huddersfield; he was rewarded with a baronetcy following his interrogations which forced Luddite members to turn King’s Evidence and resulted in the hangings.

In pride of place at the Shears is the impressive badge of the croppers for all to see. After the trial the Shears ceased to be the headquarters of the local Luddites, but continued to be what it had always been: an important feature of the locality’s social life.

ROBERTTOWN, LIVERSEDGE: Star Inn

Roberttown: M1 J40, then A638 to Dewsbury and Heckmondwike. At A62 turn towards Huddersfield. Keep right for Roberttown.

Although the name of this pub has no connection with the woollen industry, it played a vital part in the tragedy of 12 April 1812, following the doomed attack by the Luddites and their followers on Rawfolds Mill the previous night (see pages 148–9).

In the knowledge that troops were looking for the conspirators, they became fugitives, desperate to avoid capture. The two so seriously wounded that their lives were in danger, Samuel Hartley (24) of Halifax and John Booth (19) of Huddersfield, were taken by the authorities first to the Yew Tree Inn, now a private residence called Headland Hall. This was originally a clothier’s house of 1690. It seems that crowd trouble was feared, so Hartley and Booth were transferred to the Star Inn; their suffering must have been dreadful, considering the cruel journey from Rawfolds to hilltop Roberttown, then the move to the Star that followed. The landlord of the Star Inn was greatly concerned at the involvement of his pub in all this, as he had the reputation of keeping one of the most orderly houses in the district.

Both Hartley and Booth died within hours of their arrival at the Star, neither revealing any information to the authorities. A grim tale is repeated in all accounts of the night’s happenings concerning the Revd Hammond Roberson, who visited the dying men. He was commonly believed to be anti-Luddite and it was alleged that his purpose in seeing them was to obtain information. The dying Booth is reported to have said to him, ‘Can you keep a secret?’ When the parson immediately said he could, Booth replied, ‘So can I’. The deaths at the Star ended a short but very sad chapter of the Star’s history.

Life at the Star had not always been like this. In happier times it was a popular venue for visitors to the annual Roberttown races that took place on Peep Green. The common land stretched some distance from the Star, and at one point the course crossed the main road; on one occasion the horses ran into a wagon and a jockey was killed, resulting in the races being replaced by a village fair.

The Star consists of two houses joined together on a sloping site. Originally the Star was built with a corner door, a common arrangement for local shops and pubs, and consisted of one room with a small bar in a recess facing the door. Stonework alterations show this, as they do along the side of the building where a bay window has gone, also an entrance door; there is now a modern stone porch. Inside, the extension into the lower level building made steps necessary into a second area with a large bar and a conservatory.

At one time there were stables at the rear, where the local chimneysweep kept his horse and cart and pigs were bred. Photographs from the 1920s show the pub with a large notice proclaiming ‘Springwell Ales’, which came from a former brewery at Heckmondwike.

The Star Inn at Roberttown, Liversedge.

Village life at Roberttown for generations depended on spinning and weaving. Curiously, in this predominantly woollen area, the late nineteenth century saw an ‘invasion’ of workers brought by John Wright to weave cotton at Roberttown. Cottages known as Cotton Row were built to house them, the workers being fed close by at Rattlecan Hall. This weaving went on until the Second World War.

Life has been hard at Roberttown, especially at the time of heavy unemployment in the nineteenth century. It is particularly sad that the events of April 1812 should have spilled over to Roberttown and the Star Inn.

HILLHOUSE: The Slubbers Arms

Hillhouse: From Huddersfield Ring Road take A641 Bradford road. At first lights turn left, The Slubbers opposite.

Since its opening in 1853 the pub’s name has remained unchanged. It is believed to have been chosen because the then owner’s son was a slubber. In the textile industry slubbing is the removal of knots of wool following the carding process. The Slubbers at Huddersfield is the only pub with that name in England, making it a unique part of the local industrial scene.

The intriguingly named Slubbers Arms.

The address of The Slubbers, 1 Halifax Old Road, shows the pub to be located at Hillhouse, at the start of an early route to Halifax. Looking from the traffic lights on Bradford Road, Huddersfield, today it is clear that this has always been an important crossroads where travellers leaving Huddersfield turned from the route to Brighouse and Bradford and climbed steeply to go over the top towards Elland and Halifax.

Within a few yards the roads divide, with The Slubbers standing on a sharply pointed junction created by the road pattern. The result is a door at the pub’s ‘sharp end’ with the building widening towards the rear, where neighbouring property has been taken over as an extension. In the nineteenth century, when the pub was built in a congested area of workers’ dwellings, it must have seemed a good location for business and a corner position of great potential. In Huddersfield’s textile heyday there would have been six mills or so in the immediate vicinity, bringing in plenty of business for The Slubbers and other nearby pubs.

The bar today has some fine examples of textile items, a collection of ale jugs and bottles, reminiscences of the glory days of Huddersfield Town Football Club – indeed a massive display of what the licensee calls paraphernalia. A bona fide 1888 fire range is quite surrounded by textile industry photographs and posters, including ‘Rules of the Mill’ and ‘Rules for the duties of an Overlooker’.

While the bar and snug are full to the ceiling with the collections, the games room at the ‘sharp end’ has quite a different atmosphere. There is no piped music at The Slubbers, but plenty of conversation. The pub was awarded the Winter Pub of the Season 2003 by the local branch of CAMRA, but whether there is any connection between the no music regime and the award must remain a personal point of view!

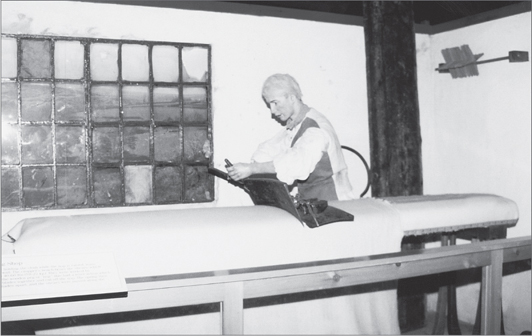

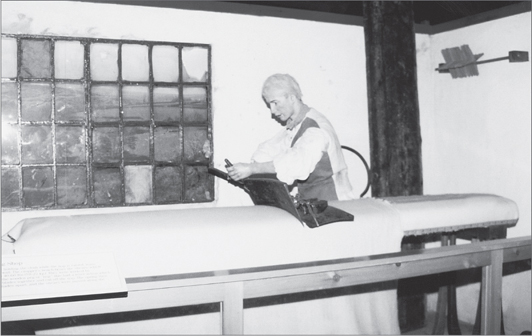

MARSH: THE Croppers Arms

Croppers Arms: M62 J23, A640 towards Huddersfield centre, or From Huddersfield A640 Rochdale Road. Pub ½ mile from town centre.

One of the finishing processes in the production of woollen cloth involved the hand raising of the nap, followed by the use of shears to ensure that the cloth had an even, smooth surface. The name Croppers Arms would appeal to the many textile workers in the Huddersfield area, especially the highly skilled hand croppers or shearmen in or near Marsh.

Exterior of the Croppers Arms.

The Croppers Arms contains some interesting pictures and memorabilia.

‘Cropping’ at the Tolson Memorial Museum, Huddersfield.

In the mid-nineteenth century it was a beer house with something of a bad reputation, and was eventually closed because of gambling on the premises. It appears to have been three cottages originally, although oddly it only has one cellar, which might argue that it was purpose-built as a pub. At the end of the century it was owned by the Wappy Spring Brewery, which used to stand in Lindley Moor Road by the side of the still-existing Wappy Spring pub.

When the licensee of the Imperial Hotel in Huddersfield calculated that a pub on Westbourne Road in Marsh would be a good proposition he was quite right, but the only way he could secure a licence there was by means of a transfer. He persuaded the magistrates to transfer his Imperial licence to the Croppers Arms in 1909 and took his chance. It turned out that he chose the right spot at the right time.

The location of the Croppers Arms on one of the main routes into Huddersfield and close to the town centre is certainly one of the factors in its success. Marsh itself was once a separate community, probably taking its name from common land on the boundary of the town of Huddersfield. Old maps show the land marked by a stone cross which has now disappeared. Today Marsh is very much a part of Huddersfield township, but retains an identity of its own. Certainly the pub has a large number of local regulars as well as many visitors from beyond Marsh. Evening bar meals are hugely popular and the present licensee has developed residential business by offering four en-suite rooms. Apart from the bar accommodation downstairs, there is a separate dining room.

Unlike many pubs these days, there have been very few changes of landlord: only five in the life of the Croppers Arms. Possibly not a world record, but as good as any recommendation a pub can have.

NETHERTHONG: Clothiers Arms

Netherthong: A616 Huddersfield –Sheffield to Honley, at Honley fork right A6024 towards Holmfirth, turn right at mill buildings on both sides of road, B6107, keep right in village for Clothiers.

From Berry Brow on the fringe of Huddersfield, a journey of 15 miles up the Holme Valley in the nineteenth century would have passed close by sixty woollen mills. So say the regulars at the Clothiers with some pride, although the great attraction of water power has long since gone and most of the mills have disappeared along, sadly, with very many jobs.

The pub takes its ‘woollen’ name from the men who were the organisers and financiers when industry was based in homes and every member of the family had a role in the work involved. In such a dispersed system there was a need for businessmen to supply the raw material – wool – to the many spinners, weavers and finishers, and then to market the product. These businessmen were known as clothiers and the pub’s name confirms what is evident from the many mullioned upper windows of Netherthong’s cottages, that it was a weaving village.

Close to the centre of Netherthong with its narrow streets wandering in all directions, the Clothiers Arms is also the centre of social life in the village. It looks little different today from a picture of 1885, when it carried the same name. Inside, the separate rooms have been opened out into a spacious bar and lounge. From all parts the bar in the corner is in full view, a great help when reordering! And in bad weather it is only a step from the houses opposite to the bar of the Clothiers and company of the Netherthong regulars.

In 1847 Deanhouse Mill was built in the village, using a stream to turn a water wheel for power. Unusually, it dealt with cashmere fleeces, but by 1950 it had closed. Change in the village was very rapid in the twentieth century; at one time there were fourteen shops, but today a post office and a general store have to provide for day-to-day needs.

Netherthong used to be very isolated and self-contained as a hill-top village some 700ft above sea level and served by steep, narrow and winding roads from the Holme valley. This must have produced a way of life that many of the ratepayers wanted to retain, to judge by a public meeting called by the local Chief Constable in February 1866 in response to village opposition to a proposal for a new road to Bridge Mill. The mill buildings occupied both sides of the Huddersfield road in the valley just outside Holmfirth. Of course, in the end change had to come and the new road, steep like the old narrow routes, was built and brought villagers much closer to the wider world.

Outside the Clothiers Arms.

The strange use of ‘thong’ at Netherthong, and at its slightly larger neighbours Upperthong and Thongsbridge in the river valley, comes from an early word for a strip of land and from the Danish for a military gathering place. Thong may sound strange, but the people of the village are warm and welcoming, as any visitor to the Clothiers will soon discover.

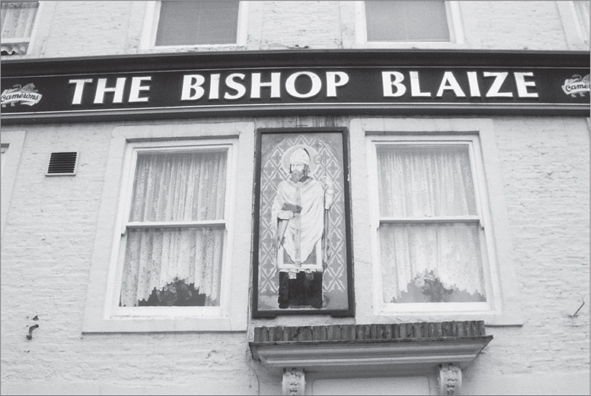

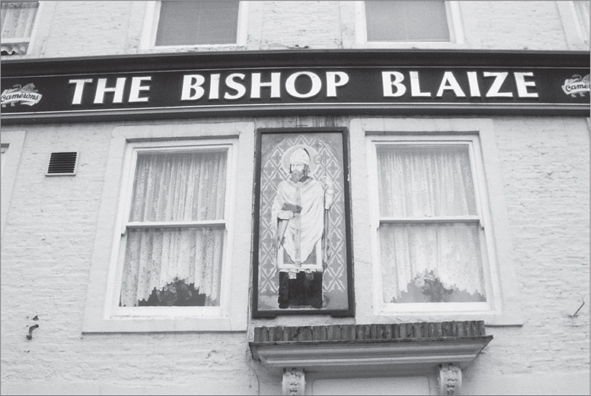

RICHMOND: The Bishop Blaize

Richmond: A1/A1M to Catterick, then A6136.

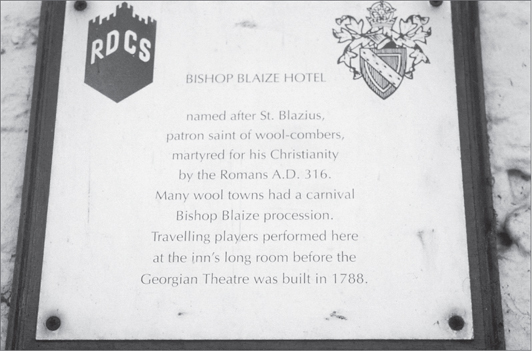

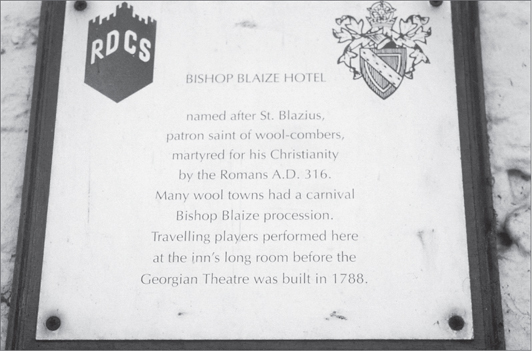

Of all the pubs in Yorkshire carrying names connected with the woollen industry, here in the Market Place at Richmond in the twenty-first century is an example few people would recognise. Fortunately a plaque on the wall of the Bishop Blaize in Richmond unveiled in 1992 now records the link with St Blazius, who was adopted as the patron saint of woolcombers.

Martyred in Armenia by the Romans in AD 316, he was tortured and put to death by the use of iron combs to tear his flesh. The similarity of these to the combs used by woolcombers in the early textile industry made him greatly venerated; indeed, some believed him to have invented woolcombing. His emblem has two crossed candles and a comb. Combing is, of course, a preparatory process in the woollen industry.

The Bishop Blaize premises were probably used for wool distribution in Tudor times. In a town such as Richmond there would have been many houses where spinning or weaving was a home industry and the countryside around supplied the fleeces to textile workers. The pub’s position on the Market Place would have added to its industrial and commercial importance, but its cultural contribution should also be remembered. In its long room plays were performed by travelling actors in the years before the famous Georgian Theatre was opened in the eighteenth century.

The Bishop Blaize, Richmond.

Like other Yorkshire wool towns Richmond would celebrate the Feast of St Blaize on 3 February. In large cities such as Bradford there was an annual dinner and festival with a huge procession of hundreds of workers from all the textile trades including, of course, the woolcombers. Flags and colourful costumes were displayed and bands played.

These activities were at their greatest and finest in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries just as the factory system had begun to transform the woollen industry. It was mechanisation and the fear of the loss of jobs that brought an end to the festivals that were held every seven years and to the public commemoration of the martyrdom of St Blaize.

TODMORDEN: Weavers Arms

Todmorden: M62 J20 to Rochdale, then A58/A6033. Or M65 J10 to Burnley then A646.

By all the rules, the Weavers Arms should not have survived. An old postcard shows the entry to Silent Lane from Burnley Road, Todmorden, partly hidden by shops, including a newsagent’s shop on one corner and the Oddfellows Arms on the other. The shops have now gone and the Oddfellows’ conversion to apartments has changed the scenery, but the Weavers’ landlord believes that Silent Lane is aptly named because you can miss it so easily, as he did on his first visit.

As recently as 1939 there were thirty-three cotton mills and associated businesses in Todmorden; not one mill is operating today. The Weavers’ neighbour was once the huge Adam Royd Mill owned by Charles Crabtree Ltd, now gone like the rest, its premises occupied by companies producing metal units and electrical equipment. The courtyards of weavers’ cottages, tiny houses reached through arches and alley-ways that housed many of the pub’s customers living opposite were cleared; the area is now a car park.

The Weavers Arms.

If the Weavers Arms had been a bigger pub, the loss of three cotton mills in its immediate area would have spelt disaster, but it is a single room establishment with a small bar and one snooker table. It does not need many customers to be crowded and everyone knows everybody else.

An old issue of the Todmorden Official Guide refers to it as a beerhouse and lodging house in 1851. The lodging house notice that once existed on the wall can no longer be seen, neither is there an obvious sign of the accommodation needed for lodgers. An attic window is high up at the Burnley road end of the building, but a row of cottages is built against the opposite gable end. It must have been very dark and extremely cramped when the innkeeper, his family, a servant and the lodgers, thirty-five people, were all at home. But cramped would have perfectly described the nineteenth-century living conditions in the whole area round Silent Lane.

Todmorden is an extraordinary town by any measure, linked by its valley communications to Rochdale and Burnley in Lancashire rather than via the Calder valley to Yorkshire. In fact, until 1888 the town was divided, the boundaries of the counties passing through the Town Hall, where the pediment on the façade has representations of Lancashire industry on the left and those of Yorkshire on the right.

The Freemasons Arms, once a next-door neighbour to the Weavers Arms and now apartments.

The steep valley sides limit Todmorden’s sunshine hours and on an overcast day its character as a former mill town is plain to see. In 1829 the Fielden company had the largest weaving shed in the world; the other big cotton families were the Cockcrofts and the Crabtrees. The railways came, of course, and there are two massive stone viaducts at opposite ends of the Burnley road.

Yet industrialists were also benefactors and reformers. John Fielden, MP for Todmorden, who became rich through cotton, worked for improvements in factory conditions and supported the Ten Hour Bill. He is buried at the Unitarian church of 1865 built by his sons in his memory; their fine family home was in Centre Vale Park across the Burnley road from Silent Lane and the Weavers. Both house and park are now open for the benefit of the public.

One of Todmorden’s proudest claims is that it is the only town in the world to have had two Nobel prize winners: Sir John Cockcroft in 1951 for his research in the field of nuclear physics and Professor Sir Geoffrey Wilkinson in 1973 for his work in chemistry.

WHITLEY: The Woolpack Inn

Whitley: M1 J38, A637 to Grangemoor roundabout, then B6118. In Grangemoor village turn at Whitley sign.

Located at the corner of Scopsley Lane in the small village of Whitley south-west of Dewsbury, the pub is just 2 miles from the larger settlement of Thornhill. Both places were typical textile villages in the days of domestic spinning and weaving, but once mills using water power were built in the river valleys, towns like Dewsbury and Huddersfield grew and many workers left villages such as Whitley for work in the towns; others went to work in one of the Thornhill local mines.

Going back over 200 years to the early days of the pub, much wool traffic would have passed by the corner of Scopsley Lane on its way from the Barnsley and Sheffield area to cross the Pennines to the wool markets of Manchester. Horses or mules and their drivers would have been glad to see the pub and be able to halt there for rest and refreshment. Their heavy woolpacks will have given the pub its name, one easily remembered by travellers in general as well as by the regular wool men.

The Woolpack at Whitley, outside and inside.

The Woolpack’s beginnings were very modest, as it occupied just one room in a series of back-to-back cottages and remaining this size until 1966, when the property was sold to a local businessman. As and when cottages became vacant, facilities were extended and improved. Successive refurbishments provided a snug, a cocktail bar and a restaurant; most recently fifteen en-suite bedrooms were added.

Today the Woolpack describes itself as ‘a pub with atmosphere – and style’. It is good to see that its part in the woollen industry is remembered in the menu with Woolpack Specials and Weavers’ Specials.

The handsome pub sign recalls the years when it was the wool men who were pulling up outside; modern travellers may be different, and are glad to have a spacious car park, but the story of the Woolpack is a long and continuing one.