CHAPTER ELEVEN

After the pintxos, Professor Fauna asked Mr. Mendizabal to tell them of the herensuge.

“Legends of dragons have been told throughout this land. But each region tells its own version of the dragon story. Here in Euskal Herria—the Basque Country—we told stories of a dragon with seven heads: Sugaar, the god of the storms. Nearby, in Cantabaria, they tell the tale of a dragon called the cuélebre, who lives in a cave overflowing with treasure. In every town, they tell tales of their own kind of dragon.”

Professor Fauna cut in, “It is my belief, children, that all of the dragon legends of this coast are about the same dragon species. But each time the story of the dragon is told, it changes. Suddenly, you have ridiculous things like seven-headed dragons, like in a child’s game of broken telephoning.”

“Wait, you don’t think there’s a seven-headed dragon?” Uchenna asked.

“No, I do not,” said Professor Fauna.

“I disagree,” Uchenna replied.

The professor laughed. “On what evidence?”

“That seven-headed dragons are awesome, and I want them to be real.”

“That is not the basis for a scientific theory, Uchenna.”

Mr. Mendizabal shrugged. “I agree with the girl.”

“But what about the herensuge?” asked Elliot. “You haven’t told us about the one dragon we’re here to save.”

“Ah!” said Mr. Mendizabal. “I was just getting to her! The legend of the herensuge has been intertwined with the history of my family for generations. It begins more than a thousand years ago, with my ancestor, a sword-smith named Teodosio.

“Tay-oh-DOH-see-oh lived in Bizkaia, the region of the Basque Country where we are right now. He was a true Euskaldun: a proud man, but also a man of honor. He made a guarantee to each person who bought one of his swords that the weapon would never fail in battle. And they never did.”

“Wait, does your family still make swords?” Uchenna asked.

Mr. Mendizabal frowned. “My brother, Íñigo, runs the family steel foundry in Bilbao, but I do not believe he has many requests for swords these days. His steel is used to build buildings and boats and railroads and other such businessy things.”

“Well, if he did have any swords, I might know someone who would want one,” Uchenna said, pointing at herself with both of her thumbs.

“Uchenna,” said Professor Fauna, “this is no time for talk of swordplay. That part of your training may come later, but only if you pay attention to these valuable lessons. Please continue, Mitxel.”

Instantly, Uchenna sat up as straight as she could, crossed her hands in her lap like a model student, and turned to Mr. Mendizabal. He went on with his story.

“One day,” Mr. Mendizabal went on, “a knight’s squire burst into Teodosio’s workshop. ‘Your blade failed,’ the squire said, and he tossed a broken sword onto the floor. ‘My master was escorting a noblewoman through the mountains. He heard of a dragon living in a cave nearby, so he set out to prove his courage and defeat it. My master fought bravely, but your sword could not pierce the beast’s scales. The dragon killed my master and took the lady back to his cave.’”

Professor Fauna threw his arms in the air. “What is this with people attacking dragons all the time? Why can’t they just leave them alone?”

“Exactly!” exclaimed Mr. Mendizabal. “Just like the Euskaldunak. We live in the mountains and we just want to be left alone. We need no one!”

Uchenna and Elliot glanced at each other. Who needs no one? But they weren’t about to question this tough old soldier. He went on:

“Teodosio said, ‘I promised that my blades would never fail, and now your master is dead and a noble lady is in danger. Take me to the cave, and I will rescue her!’”

Uchenna raised an eyebrow. “Hold on. Why do the boys have to go and rescue the girl? Why don’t they give her a sword so she can rescue herself?”

“This story is very old,” said Professor Fauna. “In that time, it was considered wrong for women to fight. I am sure that if you were captured by a dragon, you would not need a boy to save you.”

“Especially when I get my own sword.”

“You know,” Elliot said, “it just occurred to me that we actually might be captured by a dragon. Like, in real life. Like, maybe today.”

“Don’t worry,” Mr. Mendizabal assured him. “This herensuge would never capture you.”

“Really? Why not?”

“She would just kill you.”

All the blood drained from Elliot’s face.

Mr. Mendizabal continued with his story. “So Teodosio took the strongest and most perfect blade he had ever made and followed the squire to the cave of the herensuge. There he found the dragon, its scales glistening in the fading daylight, its brown leathery wings outstretched, perched on an enormous pile of treasure. The terrified noblewoman was trapped in the cave behind it.

“Teodosio stepped forward once. He was afraid, but what could he do? He stepped forward again. The dragon watched him come. Teodosio stepped a third time.

“Which is when the dragon lunged.

“Teodosio swung his sword.

“And the greatest blade of the greatest sword-smith in Euskal Herria . . . shattered. It shattered like glass.

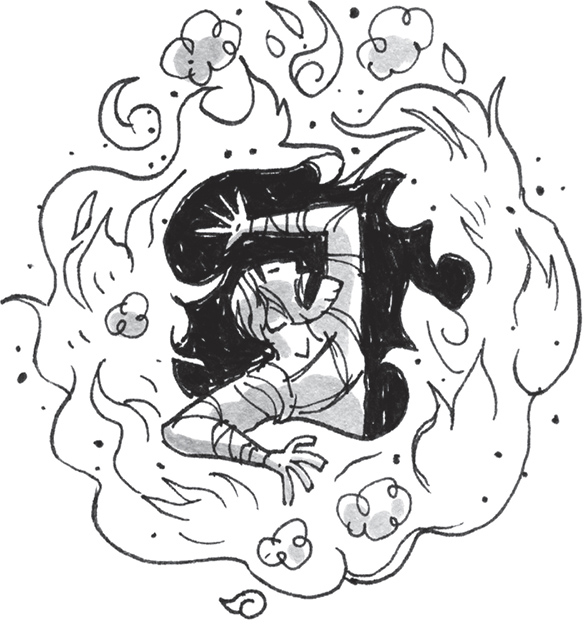

“A roar of flame enveloped Teodosio. He fell to the ground, fire covering his body. The floor was damp, though, and there were scattered puddles. Teodosio rolled to a puddle to extinguish the flame. As he did, he felt wings beating the air above him as the dragon flew out of the cave. A moment later, the noblewoman was beside him, bathing his burned skin with water from the puddles. It was blissfully cool. And then, right before their eyes, the burns healed.

“‘What water is this?’ Teodosio asked.

“‘It is the dragon’s saliva,’ said the noblewoman. ‘It is marvelously powerful.’”

“What?!” Elliot exclaimed. “She washed him with dragon spit?”

“But of course! Teodosio and the noblewoman escaped the cave and were married. Together they built a home for their new family. That home grew and changed over the years—but still it stands. In fact, you are sitting in it right now.”

“Whoa,” murmured Uchenna. “Is that really true?”

Mr. Mendizabal smiled and tugged on his mustache. “My ancestor Teodosio was a real person. He built this house, and his sword-smith trade grew into a large steel business, which we still own. For generations, though, my family believed that the story of the herensuge was merely a fable.

“Until we learned the truth.”