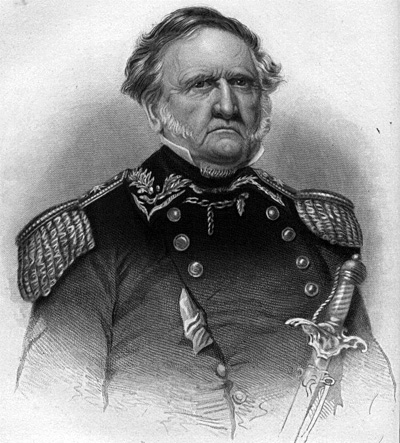

WINFIELD SCOTT (13 June 1786–29 May 1866)

Winfield Scott was born on a plantation called Laurel Branch in Dinwiddie County, Virginia. He attended William and Mary College, studied law, and enlisted as a Virginia military cavalry corporal in 1807. His official military career began a year later when he was commissioned as a captain in the United States Army Light Artillery in May 1808. Known as ‘Old Fuss and Feathers’ for his strict adherence to army discipline, Scott was the ultimate career officer. He served in the military for fifty-three years as an officer, forty-seven of those years as a general. He served under every president from Thomas Jefferson to Abraham Lincoln, a total of fourteen administrations.

In 1838, he was sent to supervise the removal of 130,000 Cherokee in compliance with the Treaty of New Echota. Scott’s troops captured or killed every Cherokee, it was said, in Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee who could not escape. They were held in extremely poor conditions inside stockades with little food until they began the long march to Oklahoma. That march would come to be known as ‘The Trail of Tears’ and go down as one of the most infamous events in United States history.

On 5 July 1841, Scott was appointed as commanding general of the United States Army, and given the rank of major general, the highest in the country. Scott was praised by the Duke of Wellington as the ‘greatest living general’. He was nominated for president by the Whig Party in 1852, but was defeated by Franklin Pierce. By the time the American Civil War broke out, Scott was seventy-four years of age, corpulent, and in poor health, suffering from gout and dropsy. He was unable to mount a horse or review troops, much less lead an army into battle. He offered command of the army to an officer he had served with in Mexico: Robert E. Lee. After long consideration, Lee turned down Scott’s offer and threw in his lot with the South, refusing to raise his hand against his home state of Virginia.

Scott, also from Virginia, opted to remain loyal to the Union and refused to resign his post in spite of his poor health. After the defeat of the Union troops at First Manasses, Scott conceived his ‘Anaconda Plan’ – to close Southern ports and send troops up the Mississippi River to outflank the South. Scott was criticized for his plan by the press, and Lincoln rejected it. Scott was further at odds with Lincoln about the way the army should be structured.

Congress was pressing for Scott’s resignation, and on 1 November 1861, Scott conceded. He was replaced by George McClellan as general-in-chief, but continued to consult with Lincoln. McClellan was the first in a string of generals who Lincoln hoped would bring a speedy end to the war. None were able to do so until Ulysses S. Grant took control of the Union forces and used the same basic strategy of Scott’s Anaconda Plan to defeat the South. Scott did live to see his plan vindicated. He died 29 May 1866 at West Point, New York, and was buried at West Point Cemetery, less than a month before his eightieth birthday.

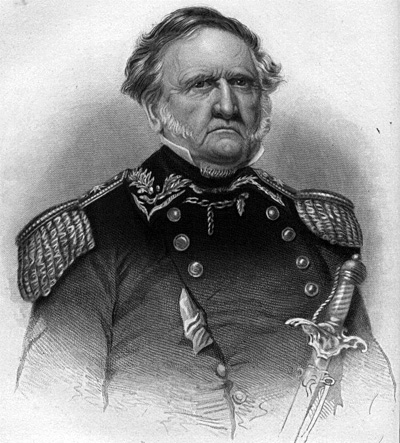

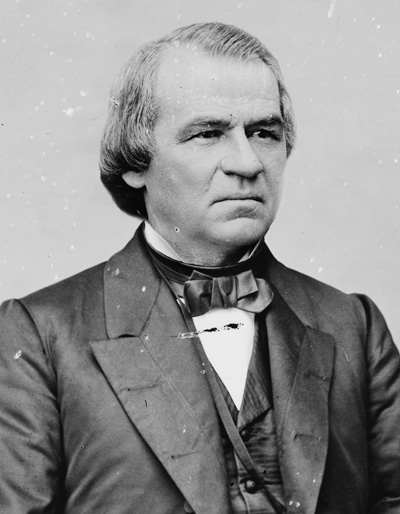

ANDREW JOHNSON (29 December 1808–31 July 1875)

Andrew Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, the son of the town constable, Jacob Johnson, and Mary ‘Polly’ McDonough. After Jacob Johnson died, Polly began to take in laundry to support her three children. It was not an entirely respectable profession. ‘Laundress’ had become a slang term for prostitutes who followed soldiers from camp to camp.

At 10, Andrew was apprenticed to a tailor. At the age of 15, he ran away, but continued to work as a tailor until the 1820s when he decided to explore the west. After travelling around Tennessee and Alabama, he helped his mother and stepfather relocate to Greeneville, Tennessee. In 1827, Andrew married 16-year-old Eliza McCardle. They had five children.

On 4 January 1834, Johnson was elected mayor of Greeneville and, in 1835, he was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives. He began to earn a reputation as a skilled orator. In 1843, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives, where he served until 1853. In August 1853, Johnson was elected as governor of Tennessee by a margin of less than three hundred votes.

When the Democratic Party was torn in two by the issue of slavery, Johnson supported John C. Breckinridge for president, along with other Southern Democrats, while the Northern Democrats put forward their own candidate, Stephen Douglas. The division in the Democratic Party opened the way for an easy victory in 1860 for the Republican Party candidates: Abraham Lincoln of Illinois and Hannibal Hamlin of Maine.

Johnson’s opposition to secession alienated other Democrats and in spite of Johnson’s efforts, Tennessee joined the Confederacy in June 1861. Johnson fled Tennessee, dodging gunshots in the Cumberland Gap. Johnson was trusted by Lincoln from early on: in March 1862, he appointed Johnson military governor of Tennessee. In 1864 the National Union Party put Abraham Lincoln on the ballot for president, with Andrew Johnson running for vice president. They won by a landslide.

Johnson was sworn into office on 4 March 1865. He apparently got drunk and avoided the public for several weeks. He would not meet with Lincoln again until 14 April 1865. Later that evening, Lincoln was assassinated, but the man who was supposed to kill Johnson went out drinking instead. Johnson was sworn in as the seventeenth president of the United States less than three hours after Lincoln’s death.

Johnson had a difficult relationship with Congress and Lincoln’s Cabinet from the beginning. He became so frustrated with Secretary of War William Stanton that he fired him while Congress was not in session. Stanton refused to leave his office, and when Congress reconvened, Johnson was charged with violation of the Tenure of Office Act of 1867, and impeachment proceedings began. Johnson was saved by one vote. He went on to veto the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, which some cite as one of the worst political mistakes in history.

Johnson sought the Democratic nomination for president in July 1868 but lost. On 3 March 1869, inauguration day, the president-elect, Grant, refused to share a carriage with Johnson, as tradition dictated. Johnson refused to attend the inauguration at all. He ran again for public office several times, but was always defeated until 1875 when he was elected once again to the United States Senate. He is the only former president to serve in the Senate after being president. He died on 31 July 1875 at the age of 66.

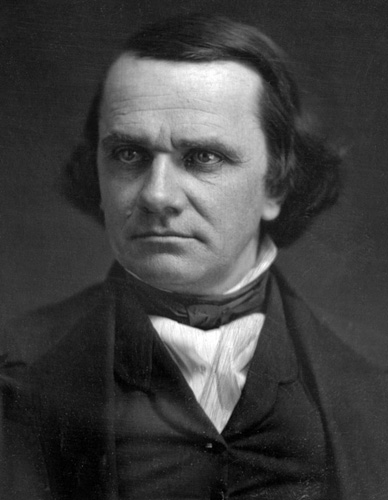

STEPHEN ARNOLD DOUGLAS (23 April 1813–3 June 1861)

Stephen Douglas was born on 23 April 1813 in Brandon, Vermont, to Stephen Arnold and Sarah Fisk Douglas. Douglas had some formal education and found work as an itinerant teacher after he migrated to Winchester, Illinois, in 1833. He began to study law and settled in Jacksonville, Illinois. Not long after, Douglas began his political career when he was appointed state’s attorney of Morgan County, Illinois. It was the first of a string of public offices. Douglas was elected to the House of Representatives in 1842, and to the Senate in 1846.

In March 1847, he married Martha Martin, the daughter of a Mississippi plantation owner. When her father died, Martha inherited the plantation, along with 100 slaves. Her husband was given control of the estate and received 20 per cent of the profits. On 19 January 1853, Martha died giving birth to a daughter who also died. Three years later, in 1856, Douglas married Adele Cutts.

Douglas sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1852 and 1856 but was passed over on both occasions. In 1858, when he once again ran for Senate, he won, defeating Abraham Lincoln. As Douglas travelled around the state, Lincoln followed in his wake, giving speeches that responded to Douglas’s speeches within a couple of days. Douglas, feeling that he was being chased, agreed to seven joint appearances with Lincoln. The Lincoln–Douglas Debates would go down in history as the beginning of a political tradition. He defeated Lincoln by a vote of 54 to 46.

In 1860, Northern Democrats finally made Douglas their candidate for president. It was considered undignified in the 1860s for a presidential candidate to make public appearances. Douglas ignored the unwritten rule and went out on the campaign trail himself. Nonetheless, in October 1860, Douglas told his secretary, ‘Mr Lincoln is the next president. We must try to save the Union. I will go South.’ Douglas duly travelled around the South, trying to rally support for the Union. When Lincoln received 120 electoral votes to Douglas’s 12, Douglas urged the South to accept the man who had been elected as president. He tried to arrange a compromise to avoid secession, which he considered criminal, and became a strong advocate of holding the Union together.

Douglas didn’t live to see the outcome of the American Civil War. He died in Chicago, Illinois, on 3 June 1861 of typhoid fever. He was buried on the shores of Lake Michigan.

EDWIN McMASTERS STANTON (19 December 1814–24 December 1869)

Edwin Stanton was born in Steubenville, Ohio, the son of a physician and a storekeeper. When he was 14, Stanton’s father, also named Edwin, died. He quit school to help assist the family by helping his mother run her general store. Stanton later returned to school, attending Kenyon College.

In 1833, Stanton returned to Steubenville where he studied law and was admitted to the Ohio Bar in 1836. He married Mary Lamson on 31 May 1836. Stanton built a home in Cadiz, Ohio, where he and Mary had two children, Lucy and Edwin. Lucy died in 1841. Edwin survived his father, dying in 1877. Mary Stanton died on 13 March 1844. Stanton’s brother, Darwin, committed suicide in 1846. The loss of three loved ones in five years sent Stanton into a deep depression that would have a lasting effect on his character.

After Mary’s death, Stanton moved from Cadiz to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he met his second wife, Ellen Hutchison. Stanton moved to Washington, DC, in 1856, where he practised law before the United States Supreme Court. He was one of the first attorneys to successfully use the insanity defence. Stanton gave up his law practice in 1860 when he was appointed Attorney General of the United States under President James Buchanan.

Stanton was a Democrat who strongly opposed secession. During the Lincoln administration, Stanton was legal adviser to Secretary of War Simon Cameron. When Cameron was accused of corruption, Lincoln reassigned him and replaced him with Stanton on 15 January 1862.

Stanton proved a very effective administrator of the War Department. He aggressively pursued the court martial of Union officers suspected of Southern sympathies. Lincoln admired Stanton’s ability as well as his obstinacy. Eventually, Stanton came to appreciate and respect Lincoln, and became a Republican. When news of events at Ford’s Theater reached him, Stanton rushed to the Petersen house and took control. He ordered the distraught Mary Lincoln to be removed and barred from the room. When Lincoln was pronounced dead the next morning, Stanton declared, ‘There lies the most perfect leader the world has ever seen.’

The vigorous pursuit of justice had begun before Lincoln took his final breath. Stanton was determined to track down and punish anyone and everyone involved in the assassination. He was so aggressive that he was accused of witness tampering and using his position as Secretary of War to control the military tribunal when the conspirators were tried.

Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, had a difficult time with Stanton. Stanton disagreed with Johnson’s policies regarding readmitting Southern states to the Union and on reconstruction. Johnson became so frustrated with Stanton that the president tried to remove Stanton from office. Johnson was overruled by Congress, and Stanton used the incident against Johnson to bring impeachment charges against him.

In 1868, Stanton resigned as Secretary of War and returned to his law practice. One year later, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Stanton to the United States Supreme Court. Although the nomination was approved, Stanton was never able to take his oath of office. He died of an asthma attack four days after the appointment was approved. His wife, Ellen, and son, Edwin, survived him.

JOHN WILKES BOOTH (10 May 1838–26 April 1865)

Even before he became famous as the first man to assassinate a United States president, John Wilkes Booth was a well-known name. Born into one of the most famous acting families in America, Booth was the ninth of ten children of Junius Brutus Booth. He was born in Bel Air, Maryland, and his mother was Mary Ann Holmes, his father’s mistress until 10 May 1851 when they were married.

At 16, he began to take an interest in the stage and in politics. At the age of 17, on 14 August 1855, he made his stage debut in Baltimore, Maryland. Booth was often described as handsome and athletic. By the time the Civil War began, he was earning $20,000 a year, about half a million dollars today. He was so strongly opposed to abolition that he joined the Richmond Grays, a 1,500 man volunteer militia group that travelled to Charlestown, Virginia (now West Virginia), in order to guard the hanging of the abolitionist John Brown on 2 December 1859 and prevent any rescue attempts.

Booth travelled throughout the South during the war, often using acting as a cover for his spying and smuggling activities. He was arrested in St Louis, Missouri, for making treasonous remarks. In February 1865, he became infatuated with a young woman named Lucy Lambert Hale, the daughter of New Hampshire Senator John P. Hale. The two became secretly engaged.

Booth’s plots against Lincoln began as early as 1864, but at first, the plan was simply to kidnap the president and hold him as leverage for Confederate prisoners. After Lincoln was re-elected, Booth began to meet with accomplices David Herold, George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell and John Surratt at the Surratt Boarding House in Washington, DC. On 12 April 1865, a boarder at Surratt’s named Louis J. Weichmann claimed that Booth told him that he was planning to quit the stage. It was at this point that the planned kidnap became an assassination plot. The previous day, Lincoln had given a speech supporting suffrage for freedmen and Booth declared to Weichmann that it would be the last speech Lincoln ever made. Two days later, Booth would make good on the promise.

Booth received word that Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant were planning to attend the evening performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theater on Good Friday, 14 April 1865. He gave his accomplices their missions. Lewis Powell was to kill Secretary of State William Seward, George Atzerodt was to seek out and kill Vice President Andrew Johnson and David Herold was to assist in the escape for which Booth had already made preparation.

At around 10 p.m., Booth forced his way into Lincoln’s box and shot the president point blank in the back of the head. The actor vaulted over the edge of the presidential box, landing on the stage and breaking his leg. He shouted, ‘Sic semper tyrannis’ (Latin for ‘Thus, always, to tyrants’), and ran offstage. A horse awaited Booth at the rear stage door and he rode out of Washington to meet David Herold. Lewis Powell forced his way into the home of William Seward and attempted to stab the secretary of state, but was unsuccessful. George Atzerodt got drunk and made no attempt on Vice President Johnson. Powell and Atzerodt were captured quickly.

Booth and Herold stopped in St Catherine where they asked for medical help from Dr Samuel Mudd. Mudd set Booth’s broken leg, but later claimed not to know who his patient was. Booth was disappointed that he was seen as a murderer in the South rather than a saviour. On 26 April 1865, twelve days after the president had been shot, Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty and twenty-six men of the 16th New York Cavalry tracked Booth to a tobacco barn on a farm in Virginia owned by Richard Garrett. Herold surrendered, but Booth refused. The barn was set on fire in hopes of forcing Booth out. Sergeant Boston Corbett saw Booth through the cracks between the boards of the barn and shot the assassin. He died two hours later. He was 26 years old.

HARRIET ELISABETH BEECHER STOWE (14 June 1811–1 July 1896)

Harriet Beecher Stowe was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, the seventh of thirteen children. Her mother, Roxanna, died when she was 5. Her father, Lyman Beecher, became president of Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio. Harriet moved to Ohio to join her father after receiving what was considered a ‘male education’ at her sister Catharine’s academy. In Ohio, Harriet met a widower and professor at her father’s seminary named Calvin Ellis Stowe. They married on 6 January 1836.

Born into a family of ministers and abolitionists who worked with the Underground Railroad, Stowe was a staunch opponent to slavery. Such was her influence that she was invited to meet President Lincoln in 1862. Her most famous work, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was the American bestselling novel of the nineteenth century and has been credited as the spark that ignited the American Civil War. It was written following the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 which declared that any runaway slaves, if captured, must be returned to their masters. Uncle Tom’s Cabin: or, Life among the Lowly sold over 10,000 copies in the first few weeks after it was published and around 300,000 in the first year.

Based on stories that Stowe heard from escaped slaves, the main character is Uncle Tom, who is sold by his owners because of financial troubles. His first new owner is a kind man and Tom bonds with his daughter Eva over a shared intense Christian faith. When Tom is sold again, following the tragic death of the father and daughter, he falls into the hands of the evil Simon Legree, who is determined to break Tom and his faith in God through savage beatings. Tom eventually dies just as the son of his original owners arrives to try to purchase him. Stowe’s powerful and emotional work converted many in the North to the abolitionist cause.

Predictably, Stowe’s book enraged white Southern slaveholders. Some Southern authors retaliated with their own ‘Anti-Tom’ literature, defending slavery and condemning Stowe’s work. Stowe wrote other novels, but will be remembered as the author of the book that was outsold only by the Bible in the nineteenth century. She died 1 July 1896 at the age of 85 in Hartford, Connecticut.