6 You Can’t Draw Your Ass

Outside the window of Art Babbitt’s transcontinental train stretched the Midwest in July. The Depression had ravaged the region since Babbitt had last been there. The national Farmers Holiday Association was in the midst of an enormous strike and export embargo as farmers demanded fair prices for their goods. Soon the strike would span seven states and barricade the highway between Babbitt’s two hometowns, Omaha and Sioux City.1

When Babbitt arrived in Los Angeles, he saw a growing city surrounded by undeveloped brown hills and dotted with red streetcars and opulent cinemas. The city exuded the mystery of Greta Garbo, the exuberance of the Marx Brothers, the austerity of Spencer Tracy, and the seediness of Edward G. Robinson.

In a miles-wide radius from Griffith Park and its HOLLYWOODLAND sign stood the movie studios: Paramount Pictures, Columbia Pictures, MGM, Warner Bros., Fox Film Corporation, Universal Pictures, and United Artists. Far beyond them to the east, in the rolling desert near the remote Silver Lake Reservoir of Los Angeles, was Hyperion Avenue. Its streets were cracked. Gophers darted across the hill facing the tall concrete wall of number 2719.

In the middle of the wall was a small gate that led to a grass courtyard and an inviting flagstone path. The path lead to a quaint Spanish colonial–style building, two stories tall, with stucco siding and a red terra-cotta roof. On it rested the neon sign in the shape of Mickey Mouse, with the words WALT DISNEY STUDIOS. Shutters hung from every pair of picture windows. Inside, everything was dazzlingly painted in bright tints of light blue, raspberry, and gleaming white—far from the institutional tones of the New York studios.2 Walt Disney’s office was on the second floor; Carolyn Shafer showed Babbitt in.

Walt Disney, age thirty, sat at his wide wooden desk. He normally donned slacks and a thin sweater, and when he wasn’t primed for publicity photos, a shock of his straight black hair tumbled over the side of his face. He wore an expression that was all business. Those who met him were surprised by his youth. “You had a feeling that there was some part of him that was either more mature than most people his age or he had a fixation about something,” one artist remembered. “From the beginning I had that feeling that this man wants things his way.”3

Walt corrected anyone who called him “Mr. Disney”—it was strictly “Walt.” When Babbitt sat down, Walt was straightforward, saying that the studio was full and could not afford to hire him. Babbitt volunteered to work for a free three-month trial period. Babbitt recollected, “[Walt] said, well, he didn’t have any room for me. I told him I only take up a space about four feet by six feet and I’m sure they could squeeze me in someplace.”4

It didn’t come to that. Walt remembered in 1942, “Mr. Babbitt came into my office and said that there was nothing he wanted more than to work for me because he thought I was doing something for the business. It was that enthusiasm on Mr. Babbitt’s part, and that sales talk, [that] was the reason I hired him.”5

Babbitt rented a house near the Hollywood Bowl,6 and started at the Disney studio on Saturday, July 23, 1932.7 The workweek was from 8:30 AM to 5:30 PM Monday through Friday, plus 8:30 AM to 12:30 PM on Saturday.8 Babbitt began as an inbetweener, earning thirty-five dollars a week.9

He was placed with a group of other new men in the inbetweeners’ room, known as the “bullpen”—in the basement of the main building. It was the days before air-conditioning, and sweating inbetweeners would often strip to the waist as they worked.10

The assembly-line process that Babbitt was familiar with at Terrytoons was similar to Disney’s, with two directors each supervising several animators and inbetweeners, though Disney animators had assistants to clean up their roughs. One artist from New York remembered, “The only difficulty in ‘adjusting’ to the Disney approach was that there was no acceptance for slipshod animation, and no thought of cost relative to quantity.”11

Unlike Terrytoons or any other cartoon studio, Disney animators didn’t have to wait months to view their work. Their rough animation was shot under a test camera, and its undeveloped film was returned to the animators the next day. This animation, called pencil tests, came back either in a strip or a loop. The animators threaded it through a Moviola machine mounted on a small table, observing their work through a lens-like aperture.12 Sometimes an action required multiple pencil tests to get just right, and each time the familiar sound of the Moviola running, “like eggs frying,” permeated the studio.13 These tests cost more time and money for the studio, and as opposed to Terry’s rate of one cartoon per week, Disney released one cartoon every three weeks.14

Babbitt was assigned to work under Chuck Couch, an animator one year younger than Babbitt.15 Couch handed Babbitt a folder containing the drawings for his assignment and gave him one week to inbetween it.

The scene was for the upcoming short King Neptune (directed by Burt Gillett), and it was a doozy. A horde of pirates had to scurry up a galleon’s mast. Babbitt placed two extreme drawings on his light disc, put a blank sheet of animation paper over them, and started to inbetween.

He came to Couch late the following day with a stack of drawings in his hands. Couch asked him if he had questions. Babbitt responded no, he had completed the assignment. Couch incredulously sent the scene to the test camera. When the pencil test came back, Couch threaded the film through the Moviola and watched it through the aperture. To his shock, the scene worked perfectly.16

News of Babbitt’s speed and skill spread throughout the studio, and soon word reached animation supervisor Ben Sharpsteen.

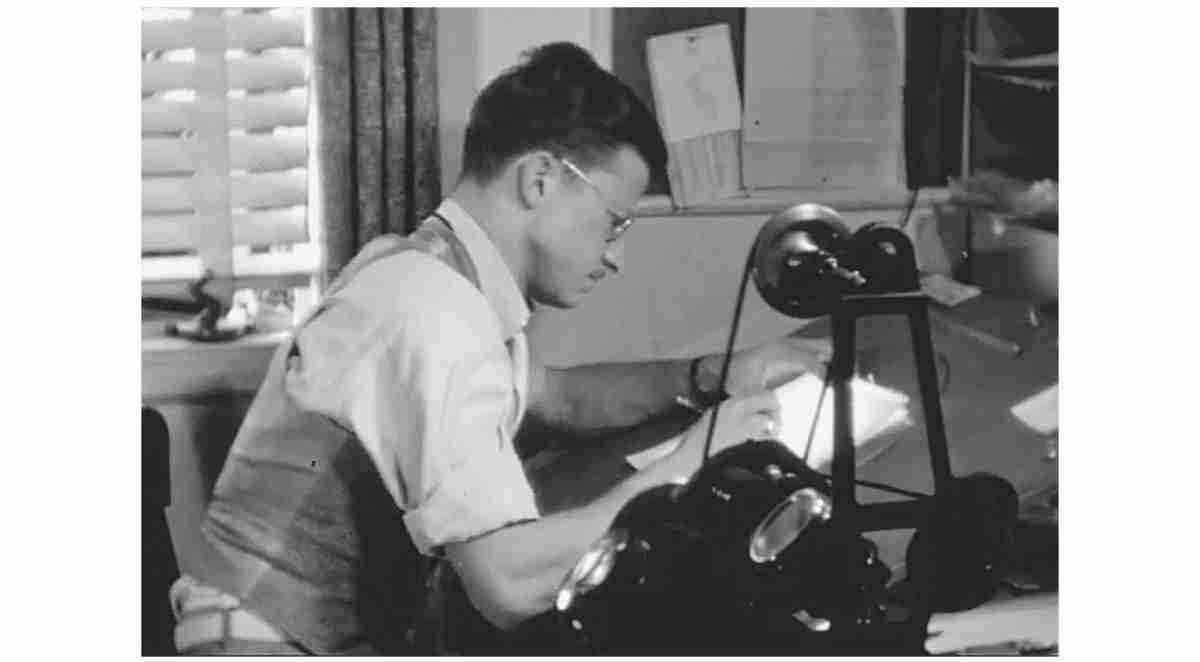

Art Babbitt animating at Disney, next to a Moviola, circa 1932.

Sharpsteen held significant sway. He had been at the studio since 1929, and now, at age thirty-six, he was among the oldest on staff. Walt had chosen Sharpsteen to manage and mentor new hires in a trainee program. Others remembered him as “a hard but fair taskmaster. He insisted on good draftsmanship, staging and action analysis. You had to learn—no shortcuts, just do it right.”17

Sharpsteen took his role very seriously. “They had to go through a very humble indoctrination,” Sharpsteen later said of the trainees, “learning how to animate the way we did, learning how to pick your work apart, learning how to diagnose, learning to cooperate with others, learning to accept criticism without getting your feelings hurt, and all those things. We had a saying, ‘Look, this is Disney Democracy: your business is everybody’s business and everybody’s business is your business.’ If you did not have that attitude, you were not going to stay very long.”18

Sharpsteen would personally review Babbitt’s next animation test. If Babbitt passed, he would advance from the inbetweeners’ bullpen to Sharpsteen’s mentorship.

A folder with Babbitt’s next assignment appeared. It was for Touchdown Mickey (directed by Wilfred Jackson), and it was of just one character, Pluto the pup. However, this scene required Pluto to display a thought process and a change in emotion—in essence, to act. Pluto was to casually move to screen right, do a take, and run back to screen left in a panic. This required a four-legged walk and a four-legged run. Babbitt began animating. If Pluto’s timing was off, the character would seem mechanical and fake. If it was good, Pluto would come alive.

The scene was approved. Babbitt became a trainee in Sharpsteen’s unit, and he was moved to a new animation room among seven others, including Couch.

The distribution of scenes from supervising animators to trainees was called “the handout,”19 and each trainee tackled his handout for the next Mickey Mouse cartoon, The Klondike Kid. Director Wilfred Jackson assigned challenging or important scenes to his top animators, and the remaining scenes would provide a training ground for Sharpsteen’s unit.20

As the days wore on, the other trainees began taking their summer vacations. Babbitt could not; he had not yet earned his vacation time. So, while his coworkers left their desks unattended, Babbitt tackled their scenes as well, and handed those in.21 In all, Babbitt completed ten of the film’s sixty-six total scenes. He had out-produced every other animator on the cartoon.

Walt spent much of his creative time with the Story Department (a far cry from Paul Terry’s gag file). Nonetheless, Walt had an awed admiration for his animators, the “actors” of his studio who breathed life into the characters. Walt wanted to capture what Charlie Chaplin had, and it was not only the gags. The hot-button word across the studio was personality. But without any formula for conveying personality, the directors grasped blindly, hoping for success with each attempt.

The Disney studio was a Hollywood anomaly. It was the largest and most critically acclaimed cartoon studio in the world, yet it was dominated by men and women in their twenties. There were baseball games on a makeshift field in the studio lot, pitting the Marrieds against the Singles. To tame the studio culture, Walt staggered the lunch hours between the male-dominated Animation Department and the female-dominated Ink & Paint Department. This didn’t stop the staff from comingling, or, as they called it, “dipping your pen in company ink.” Amorous couples would shack up at local hotels, the men all signing the same alias for the registry: “Ben Sharpsteen.”22

From the sporty to the bohemian, the coarse to the sophisticated, the studio “had a conglomeration of various types of people, all thrown in together, which made things very interesting,” remembered an early animator.23 These artists all shared a goal: to be the best. This caused the most biting insult to be “You can’t draw your ass!”24

One of the animators that Babbitt gravitated toward was Les Clark, a fellow who could “draw his ass.” Although Clark was more experienced and had been with the studio since the Oswald cartoons, the two had a lot in common. Clark was also born in 1907; like Babbitt, his father had a spinal injury that caused Les to become the family breadwinner, and he had worked as a commercial artist to make ends meet. Also like Babbitt, Clark strove for perfection in his work. His assistant recalled, “He would get you all the quality that was within him.”25

Babbitt and Clark shared meals as well as weekend camping trips. Rather than the sports lovers or the jokesters, they were among the studio’s quiet intellectuals. However, Clark differed from Babbitt in one key way that would become evident in the years ahead. Clark had an unwavering loyalty to Walt.