8 Three Little Pigs

BY DAY THE DISNEY animation wing was abuzz with experimentation. The animators had already advanced far beyond anything that had been done before, and new tricks were being discovered every day. After hours, when an animator left for home, Babbitt and the others would pick up a stack of drawings from that animator’s desk and flip the pages. Bursts of invention rippled through the whole department, mostly coming from three animators in particular: Fred Moore, Dick Lundy, and Norm Ferguson.

There was something youthful in Fred Moore (beyond being only twenty-one), and many of the fellows called him “Freddie.” When he drew, he perched jauntily on the edge of his chair, his curved pencil strokes perfect each time.1 His ability to make appealing designs was uncanny. It was Moore who had redesigned Mickey, discarding the mouse’s thin limbs and long snout for shapes that were rounded and childlike.2 As Mickey’s design had changed, his personality morphed from that of a trickster to an all-American kid. Moore was slowly becoming the studio’s specialist in animating Mickey Mouse and anything else that was round and cute. This included drawings of young nude women, and his sketches of coy nymphets with perky breasts and supple buttocks became known as “Freddie Moore girls.”3

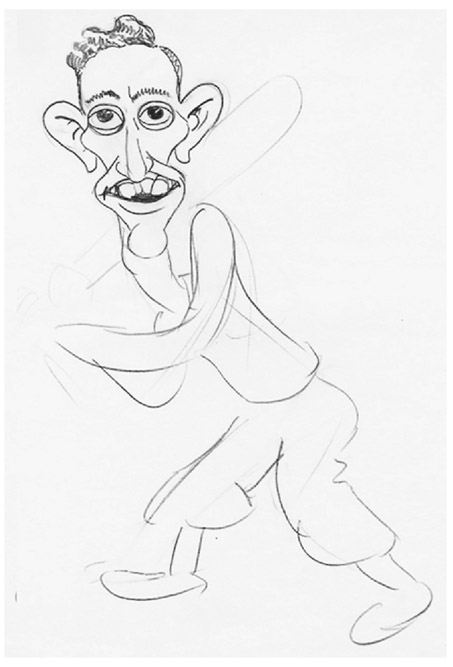

Dick Lundy, age twenty-six, had been at the studio for three years. In that time, he had found his own way to give his animation personality. He had discovered that each character can have a signature movement and a distinct action for a particular emotion. He thought of it as giving a character a dance that fit the tone, one that the audience could identify.4 In a couple years, Lundy would become the studio’s Donald Duck specialist.

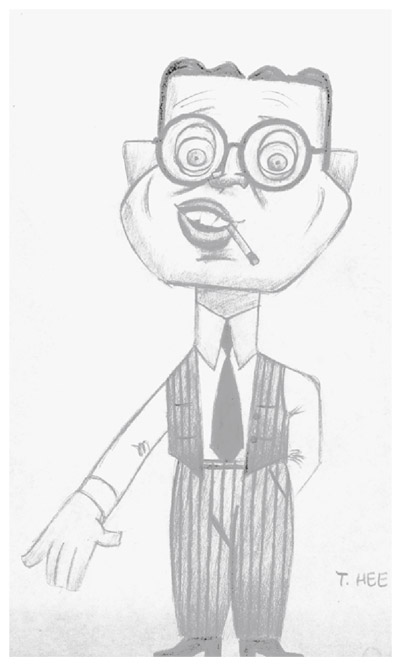

Norm Ferguson, or “Fergie,” was a senior animator at thirty years old. He had a nervous New York energy and as he drew he constantly jiggled his feet.5 He was a little dressier than the others, regularly wearing a vest and tie, but his habits were purely zen. He had a practice of zoning out while sketching, abandoning clean and crisp lines for messy, impulsive gestures. He attempted to get into the minds of his characters, and when animating he added pauses to show that the character was thinking. He was a master of pantomime, was called the Charlie Chaplin of the studio, and would soon be known as the studio’s Pluto specialist.6

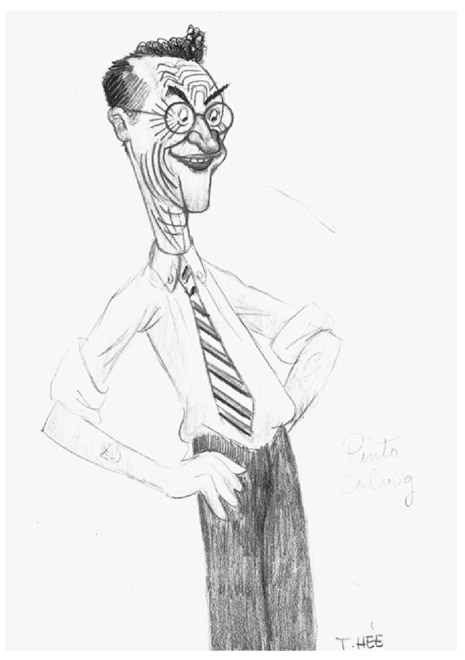

Pinto Colvig, by Disney artist T. Hee.

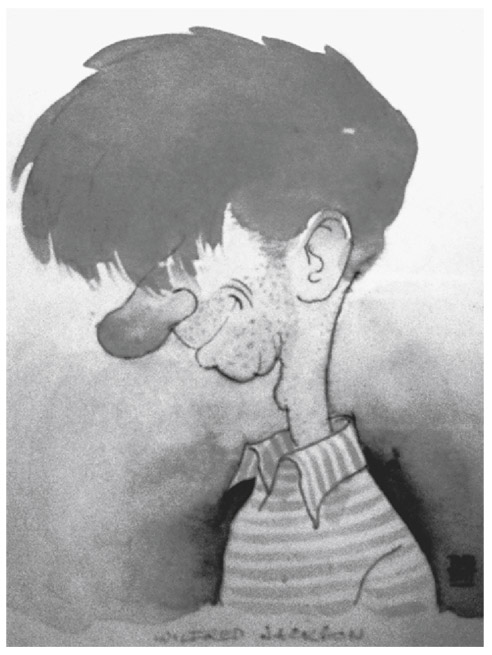

Wilfred Jackson, by Art Babbitt.

Norm Ferguson, by Disney artist T. Hee.

Dick Lundy, by an unknown Disney artist.

Fred Moore, by Fred Moore.

The Story Department took its role seriously as well. These half-dozen men tackled each story session with integrity to plot and character, critiquing and revising. They had a reputation to maintain as the best in the business.

The story team, including Walt, pitched idea after idea to each other. When Walt proposed a rough idea for a “Three Little Pigs” cartoon, his staff wasn’t sold on it. It took Walt time to workshop it in his mind until the idea of the pigs dancing and playing different instruments crystallized. He pitched it again, and this time the story men accepted it. “I don’t mean they threw up their hats, or that even I thought it would be a tremendous hit,” said Walt at the time. “We considered it a typical Silly Symphony.”7

Walt had learned that he could only sell ideas with clear visions. This lesson would play into everything he did from then on.

While the radio played “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” the first public memo for Three Little Pigs circulated in the studio. As expected, Walt wrote that he sought “to develop quite a bit of personality in them.”8 By mid-December the Story Department completed a three-page outline,9 which was tacked on the bulletin board as an open call for gag ideas. A good gag could earn the submitter a twenty-five-dollar bonus—about a week’s salary for the lower-bracketed employees.10

Like all Disney cartoons, there would be music throughout, and the pigs would disclose their motivations in song. Frank Churchill sat at his piano and tickled a little trill on the keys. Story men Ted Sears and Pinto Colvig helped with the lyrics, asking, “Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” with Colvig providing the voice of Practical Pig.

Fred Moore was assigned as lead animator for the cute pigs. Dick Lundy was to animate them dancing their jig—an exercise in character choreography. Norm Ferguson would supervise the animation of the Big Bad Wolf, whose cunning had to be evident to the audience.

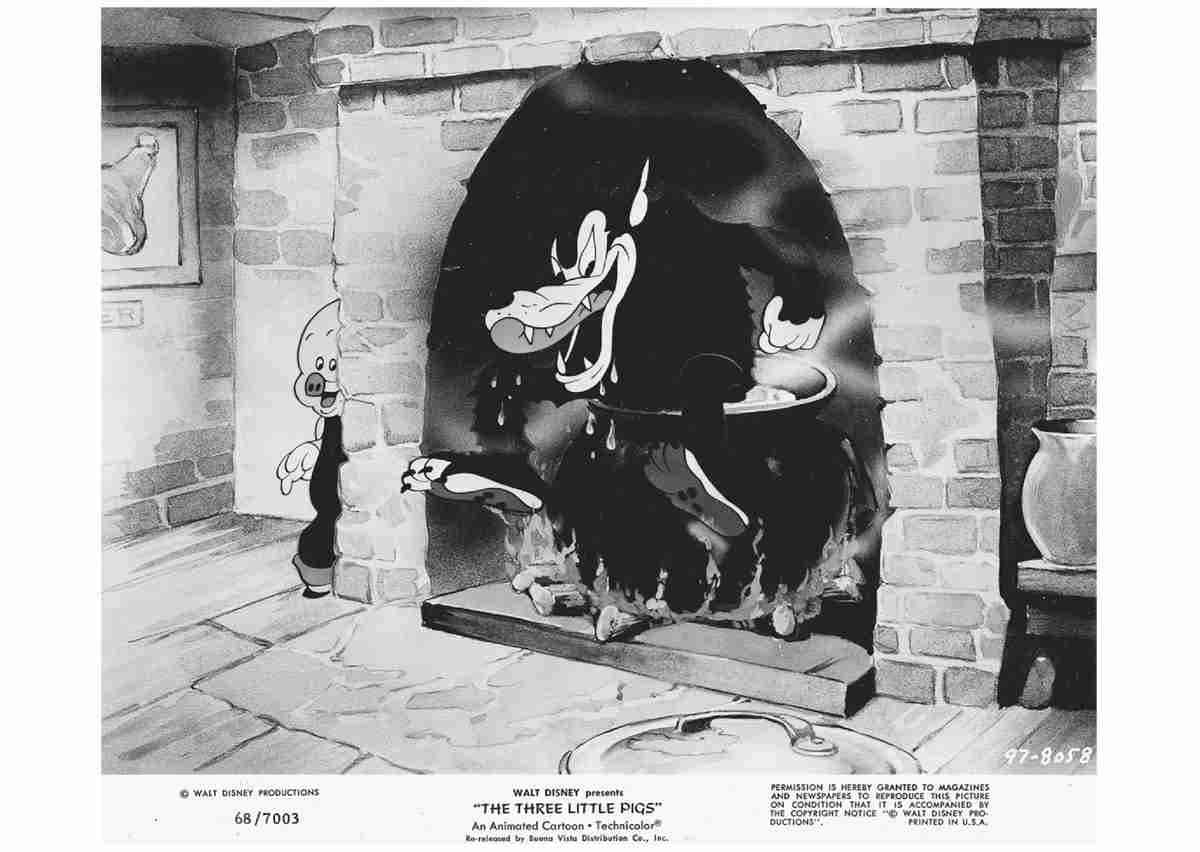

Following Babbitt’s work animating the villainous Mad Doctor and dastardly Dippy Dawg, he was given a few scenes of the wolf. He had a short scene in which the wolf grabs the first two pigs by the tails and collides into a tree. He would also handle the climax: the wolf climbs onto the brick roof and squeezes into the chimney like it was a girdle; Practical Pig removes the heavy lid off his cauldron and pours the contents of the heavy turpentine can into it; the wolf dips himself in, registers pain, and shoots up out of the chimney howling, dragging his fanny off into the horizon.

Walt had several goals with this cartoon. The wolf had to appear cunning; the pigs had to appear organic. But most important, he wanted the identical pigs to exhibit individual characteristics. This was tricky. Actors in the movies were always distinguished by their unique looks, as were Mickey Mouse, Dippy Dawg, and the rest. However, the Three Little Pigs all shared the same basic design; it was how they acted in the cartoon that would differentiate them. While Burt Gillett was directing the cartoon, Walt practically lived in Gillett’s music room, spending more time on it than he had on any cartoon yet.11

Babbitt’s scenes were assigned on Monday, February 20, 1933, and were due in seven weeks.12 Gillett went over the timing notations, as written on the exposure sheet, with the other animators. The layout man provided drawings of what the final staging would be. With his exposure sheet and layouts at his desk, Babbitt made his drawings. He flipped the pages, erasing and redrawing as needed, passing them along to an assistant to be inbetweened.13 When he had a stack of drawings ready to be pencil-tested, he had them delivered to the test camera. The roll of test film arrived the next day, and Babbitt ran it through the Moviola.

Babbitt was in the habit of staying at his desk after hours. He had fashioned a workspace that he found comfortable and inspiring, placing some expressionist art atop his desk. It was a print of Paul Cézanne’s painting of a green jug that he had bought for eighteen dollars and had framed himself with four pieces of door molding from a hardware store.

Late in the evening, when most of the staff had left for the day, Walt walked up and down the narrow corridors of his studio, smoking his cigarette and peeking into the animators’ rooms. Each room had several animation desks, and each desk had several hundred drawings stacked on its shelves. Some stacks were nice and neat, and others were a haphazard mess. Some stacks were tall; some were not quite tall enough. At this, Walt might lower one eyebrow and raise the other, a signature expression that his animators knew all too well.

Babbitt would retell one exchange that occurred when Walt found him drawing at his animation desk after hours. According to Babbitt, Walt pointed to the Cézanne print and lowered his brow.

“I don’t like it,” Walt said.

Babbitt stopped and asked why Walt didn’t like it.

“The top of that goddamned jug is crooked!” said Walt.

Babbitt argued in favor of expressionism, relating it to animation such as how Mickey’s appendages might vary their length as needed.

“Anyway, I don’t like it,” said Walt, and left. Babbitt bitterly packed the Cézanne print and took it home.14

While animating the pigs, Fred Moore made an incredible discovery.

Any animator with a pencil knew the challenge of maintaining a character’s shape from drawing to drawing. Characters’ dimensions were never supposed to change.

Fred Moore tossed that aside. He did not envision the pigs as circles or even as spheres but as voluminous sacks. For a few frames, he stretched them slightly taller or squashed them slightly wider. He kept their mass consistent, not their shapes. This, to everyone’s amazement, created the illusion of appearing soft, lively, and organic.15 The studio would call this technique squash & stretch, and once Walt saw it, he wanted more of it.

Fergie made faces at the small mirror on his desk and translated them onto the page. His own eyes became those of the Big Bad Wolf. The wolf’s eyes were the keys to observing the character’s thoughts. Fergie’s wolf also glanced at the audience, breaking the fourth wall with nothing more than a sly smile.

The artists were in the midst of a breakthrough in personality animation.

Around April 1, when his animation on Three Little Pigs was nearly complete, Babbitt picked up scenes for another assignment. This cartoon, Mickey’s Gala Premiere, centers around Mickey and his friends being honored in Hollywood. The studio hired a new artist, Joe Grant, to design celebrity caricatures for the short.

Walt analyzed each scene for Three Little Pigs in the sweatbox. He especially loved how the pigs’ houses have different wall art: dancing girls for the first, boxing champs for the second, and family portraits for the third (including “Father” as a string of sausages and “Uncle Otto” as a football).16 Three Little Pigs was moved to the Ink & Paint Department, then to the Final Camera stage, and at last to the Technicolor laboratory for distribution prints.

A lobby card featuring one of the scenes animated by Art Babbitt in the groundbreaking cartoon Three Little Pigs. © Walt Disney Productions

Around the end of April, Walt and his artists sat in the back row of the nearby Alexander Theatre in Glendale and studied the preview audience’s reaction to Three Little Pigs. It was a practice they did with every cartoon the studio released, taking notes to see which gags worked and which ones flopped.17 This time, however, was different. The response was extraordinarily enthusiastic.

At the official release on May 27, 1933, Three Little Pigs was a breakout success. It “hit the country like wildfire,” remembered a Disney artist.18 The song “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” played on the radio, becoming a rallying cry against the Great Depression and what Time magazine called “the tune by which 1933 will be remembered.”19

The competition was swept up in pig fever too. Animators at MGM couldn’t stop humming the song.20 Animators at Warner Bros. looked at it “with absolute awe.” With that single cartoon, the Warner animators felt that Disney was suddenly miles out of their league.21

Original artwork from the cartoon was displayed in local theater lobbies. Below each piece were the names of the Disney artists who created it. Under one was Art Babbitt’s name.22

Audiences were paying good money to see features with Three Little Pigs on the bill, and theaters were paying Disney good money for prints of the cartoon. Variety wrote, “Three Little Pigs is proving the most unique picture property in history. It’s particularly unique because it’s a cartoon running less than ten minutes, yet providing box office draft comparable to a feature, as demonstrated by the numerous repeats.”23

The cartoon brought Walt and his company added fame, and on July 1, the Disney company was able to negotiate an enormous new merchandising deal. Soon books, playing cards, dolls, and countless toys all featured Disney characters. When a deal was struck with Southern Dairies, Walt got all his top artists to pose for a photo holding Mickey Mouse ice cream. On the studio lawn, Walt Disney, Art Babbitt, and twenty-three others smiled for the camera. The faces reveal jubilant camaraderie, like a college club yearbook photo. Babbitt appears fully at home among the group. The only person missing in his life was his best friend, Bill Tytla.

In early September 1933, Babbitt visited his family in New York. He discovered that his brother Ike had also developed a flair for performance, practicing being a one-man band. Solomon’s spinal injury had worsened, his broken body nearly entirely bedridden. Zelda Babitzky had become Solomon’s caregiver. Not wanting to burden them, Babbitt stayed with Bill Tytla’s parents, visiting Bill and the friends the two had shared. Babbitt unabashedly tried to coax Tytla to join Disney. After Babbitt returned to Hollywood, he wrote to Tytla that he would keep a light in the window for his arrival.24

Despite the popularity of Three Little Pigs, the cartoon was slow to recoup its cost. It had been an expensive cartoon to make, significantly more than the average $25,000 for a Disney cartoon. Walt presented records showing that it had cost $60,000 and had made $64,000. Some eager journalists estimated the short to have netted nearly $100,000.25 “I’ve heard estimates from outsiders, of course, placing the gross from the ‘Three Little Pigs’ as high as $300,000 to date,” said Walt around that time. “Every time I produce another Mickey Mouse or Silly Symphony, I’m accused of making another million dollars. I only wish it were true.”26

Even at this time, Walt’s prerogative was not to enrich himself or Roy (another way he differed from Paul Terry) but to reinvest everything back into the company.27 Notwithstanding, his goal of making better cartoons was not economically viable. It became clear that cartoon shorts would never command the same price that theaters were paying for feature films.28 To continue his quest for innovation, he had to move beyond shorts. Walt would have to think bigger. No one had conceived of a feature-length cartoon before. It would require more learning, more skill—and a much larger staff.

By late November 1933, while he was animating on The China Shop, Babbitt moved to a more luxurious, Spanish-style home on Tuxedo Terrace, surrounded by a bed of wild golden poppies atop a hill overlooking Los Angeles.29 It had a bar and a comfortably sized salon—perfect for hosting either a large or intimate get-together—and he still had a spare room downstairs, a yard out back, and a Japanese fellow who helped tend the house.30

“I’m not going to bait you,” Babbitt wrote Tytla on November 27, “but you could if you wished—share my house—my grand piano—my view, my 2 fireplaces—my grandfather clock—my tropical fish—my flowers—my ‘Cezanne’ and ‘Daumier’—my wines—my hills and warm weather and my houseboy (the last—with reservations).”

Babbitt went on to disclose a new ambition that Walt had shared with him: “We’re definitely going ahead with a feature length cartoon in color—they’re planning the building for it now and the money has been appropriated. Walt has promised me a big hunk of the picture.”31

It was remarkable that Walt envisioned a feature film at this early stage but also likely that he would not give further details yet. Like Walt’s initial pitch for Three Little Pigs, this feature was still rough in his mind. He needed a clear vision, and that would take some time.

As evidenced in Babbitt’s letter, there was no greater pride for a Disney artist than recognition from Walt. On the flip side, Walt’s scrutiny could be crushing. So it was for Babbitt’s work on The China Shop.

Walt and Babbitt sat in the sweatbox, screening Babbitt’s animation of the slow-moving old man leaving his shop.

There is a very good reason why animated cartoons didn’t have many slow-moving characters. Speed is easy in animation; fast action has more freedom to vary drawings from one to another. Slowness is extremely tricky; those drawings must be nearly identical, and their slight differences have to be carefully measured. It is far easier to bungle a slow-moving action than a fast one.

Babbitt’s scene was a bit of a mess. He had animated the character’s slow shuffle toward the door, yet the doorknob was on the far side of the door, and so the old man had to shuffle downstage. Then the door opened inward, and he had to shuffle backward to pull the door—then shuffle back and pull the door again. Babbitt had treated the man and the door too literally, without any creative license. Walt was not thrilled.

“You know what I’d like you to get in this character here?” said Walt.

“What?” asked Babbitt.

“Some of that exaggeration, some of that sensitivity and stuff—you know,” said Walt, “like Cézanne gets in his still lifes.”32