25 Strike!

THE PRESS CALLED THEM “loyalists.” But there were many reasons why hundreds of nonstriking Disney artists drove to work the morning of May 28, 1941. Dumbo and Bambi would not be completed without them. They also shared a gratitude toward Walt, who not only had hired them during the Depression but also had provided them with an opulent new studio. Besides, what kind of tyrant insisted on being addressed by his first name?

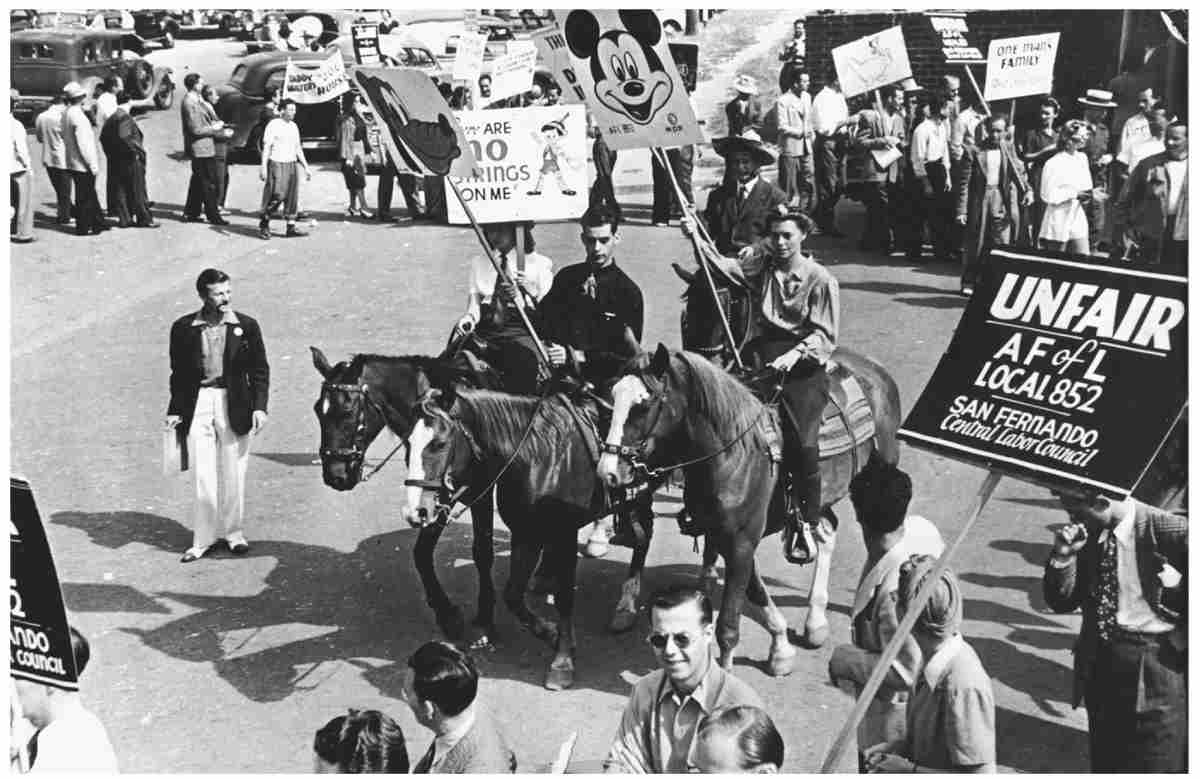

The first thing they noticed as they approached the studio was a seemingly endless line of cars parked by the curb leading to the front gate. What they saw at the Disney entrance was a spectacle they had not anticipated.

About five hundred men and women were on their feet, walking in a large circle in front of the entrance. Nearly one in ten carried wooden picket signs, many painted with cartoon characters.

IT’S NOT CRICKET TO PASS A PICKET, warned Jiminy Cricket.

I’D RATHER BE a DOG THAN A SCAB, chided Pluto.

I SIGN YOUR DRAWINGS / YOU SIGN YOUR LIVES, taunted a caricature of Walt.

MICHELANGELO, RAPHAEL, LEONARDO DA VINCI, RUBENS, REMBRANDT ALL BELONGED TO GUILDS.

The number 600 showed up a few times, too, referring to the total number of Disney artists. A strike handout reported that one sign read, ONE GENIUS AGAINST 600 GUINEA PIGS. Another had, SNOW WHITE AND THE 600 DWARFS.1

The Disney strikers outside the main gate on South Buena Vista Street.

Art Babbitt (left) surrounded by strikers outside the Disney studio.

Traffic entering the studio slowed to a crawl. As each car inched through, the strikers hooted and hollered, calling each strikebreaker a “scab” and a “fink.” A sound truck was parked nearby, providing a portable PA system to the person at the microphone.2 Bystanders and non-strikers were handed flyers titled AN APPEAL TO REASON—its title borrowed from the Socialist periodical that Walt’s father used to read.3

“The salaries of the Disney artists average less than those of house painters,” read a press bulletin. “The Disney girl inkers and painters receive between $16 and $20 a week. On Snow White, the much-publicized bonuses did not even compensate the artists for the two years of overtime they worked. Snow White made the highest box office gross in history—over $10,000,000.00. All the other major cartoon studios in Hollywood have Screen Cartoon Guild contracts. The Disney Studio is the only non-union studio in Hollywood.”4 The strikers were demanding a 10 percent wage increase across the board, a 25 percent wage increase for the lower bracketed artists, and the reinstatement of the nineteen animators—including Babbitt—who they argued were fired for union activity.

The Disney carpenters, machinists, teamsters, and culinary workers refused to cross the picket line. Electricians, cameramen, sound men, and film editors also refused.5 One striker photographed each “scab” who drove through.6 Atop a hill in the eucalyptus knoll across the street, a striker in a beret and smock stood at an easel painting a landscape of the ordeal.7 On the ground, there were “guys pouring their individual speeches into the ears of those on the fence,” wrote one non-striker that day. “I was struck with the magnitude of it all.”8

“The average age was less than 25,” said Herb Sorrell in 1948. “They became the most enthusiastic strikers I have ever seen in my life.”9 Some strikers leaped onto car bumpers;10 other rocked cars side to side.11 Once embattled drivers were through the gates, they were greeted with cheers and claps from a welcoming committee of nonstriking inkers and painters.12

The strikers had each been given two- or three-hour shifts, ensuring a twenty-four-hour picket line. They were mostly inbetweeners, animation assistants, inkers, and painters, but among them were also story artists, effects artists, background painters, and animators. Bill Tytla and Art Babbitt stood out as the highest paid on strike.

The previous night, the Guild had voted to include supervising animators among its membership. This made not only Babbitt and Tytla eligible to strike but also all other top animators. Babbitt was on his feet rallying alongside the other strikers, shouting to non-strikers by name, including Ward Kimball. “I felt terrible,” Kimball journaled that day. “Friends on the inside waving to me to come in. Friends on the outside pleading with me to stay out; Jeezus. I was on the spot!”13

Inside the studio, loyalists were worried. “How the hell can Walt run a studio without us?” asked Norm Ferguson.14 As non-strikers passed the gauntlet of pickets, strikers warned them that once the union won, it would fine them an amount equal to their salary plus $5 per day, plus a $100 penalty.15 Ferguson told his fellow non-strikers, “Any agreement made will have to involve protection for you guys or Walt wouldn’t sign, so stay on and receive your salary!”16 With nearly all the assistants and inbetweeners outside, the animators pitched in to do those jobs for each other. If the films weren’t completed, the Bank of America might foreclose. Right now, everything was riding on Dumbo, the studio’s “B” picture.

Relationships were severed. It was the end of Babbitt’s friendships with nonstriking animators Les Clark and Fred Moore. Babbitt was also dating a blonde secretary named Nora Cochran before the strike; she was unsympathetic.17

The strike took its toll on those who couldn’t choose a side. Novice animator Walt Kelly (future creator of the comic strip Pogo) had friends on both sides, and he packed up and left altogether. He claimed it was to care for his ill sister, but privately he left his friends this note:

For years I have reached for the moon

But the business now is in roon

So I don’t hesitate

To state that my fate

Is to take a fug of a scroon!18

After 10:00 AM, the strikers dispersed to the adjacent eucalyptus knoll. Sorrell recalled that “from 10 to 11 or 11:30, we would talk to them on a loud speaker system, and of course they could hear in Disney’s what we were saying across the street.”19

Every emphatic slur and enthusiastic cheer that erupted from the PA system echoed in the Burbank studio. Walt was still seen smiling at lunchtime. “I’m going to see this to the end,” he said. “I told ’em I’m willing to hold an election, but they refuse, it’s their funeral!”20

Walt was fixated on having a secret-ballot vote to determine the majority, but there was good reason for the Guild to deny an election. The Disney company, it was rumored, was fudging the numbers, counting its non-artist employees as artists. The studio released a statement that there were only 309 absences out of 1,214 total employees that day, and that there would have been fewer if not for the threat of union goons.21 The strikers knew that of those 1,214, there were hundreds of employees—from accounting to security—who were ineligible for an animators’ union.

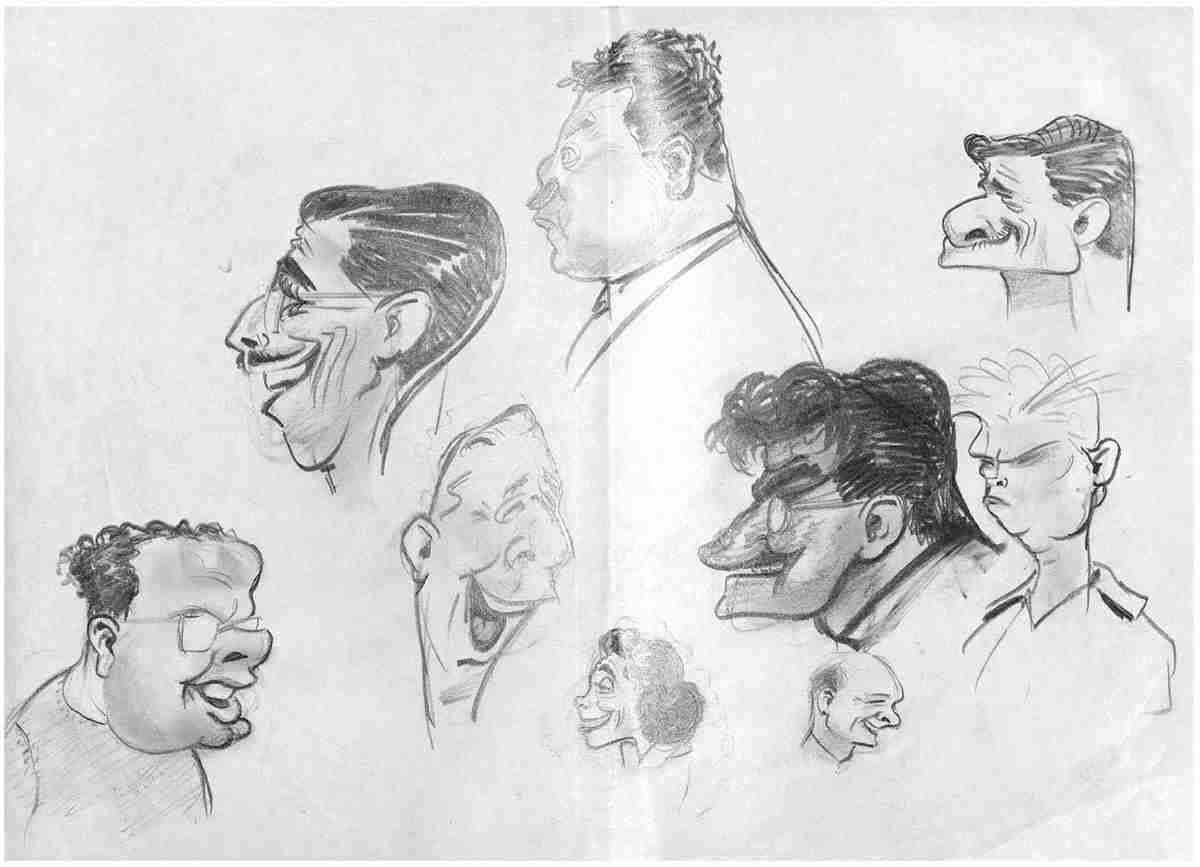

Caricatures of Disney strike leaders by a member of the strike. Top row: Pepe Ruiz, Herb Sorrell, Art Babbitt. Middle row: Dave Hilberman, unknown, Bill Tytla, Chuck Jones. Bottom row: unknown, Bill Littlejohn.

In truth, no one seemed to agree on how many artists were on strike and how many were not. Bill Littlejohn figured 450 strikers out of 580 artists,22 while Babbitt counted 375 strikers out of 550 artists.23 The Disney strikers also reinforced their numbers with spouses and friends on the picket line.24 In actuality, it was an extremely balanced divide, with roughly 330 strikers out of roughly 602 artists. (The evenness of the split was confirmed later by the Guild’s business agent.)25 It was what made the strike so adversarial. If just twenty strikers changed their vote in the heat of a company-led election, the union would lose.

Roy Disney returned that day from a New York business trip and released a statement debunking those number-fudging rumors and insisting on an election to prove it. Guild president Bill Littlejohn responded: “The request of the company for an election is made only for the purpose of beclouding the issues involved in our strike. . . . The Guild is striking against company unionism, intimidation, discrimination and persecution.” At the local Labor Relations Board office, William Walsh sent his chief investigator, field examiner George Yager, to determine just which union had rightful claim of the majority, the Guild or the ASSC.26 Alas, Yager could not.

It was a dry day out in the Los Angeles heat, but those inside were sweating too. At around four o’clock, Walt called a few trusted artists to his office. He had hired a photographer that morning to take images of the strikers on the picket line. Those pictures were printed poster-sized and lined the walls of his office, the faces of the strikers clearly visible. Walt went from picture to picture, pointing at the faces with either incredulity or ire. Roy arrived to reassure Walt, while Lessing, ever confident, promised that the strike would dissipate within a day. Walt liked the sound of that, and went to the fridge in the corner kitchen of his office and poured everyone a glass of sherry.27

As quitting time neared, the strikers swelled the gates again. Guild attorney George Bodle shouted over the loudspeaker, “Unless the Screen Cartoonists is recognized and five union officials reinstated, picket lines will be established in front of every theater showing Disney films.”28

That afternoon, the sound wagon announced that Leon Schlesinger had visited the picket line and stopped by to chat with Sorrell.29 Schlesinger was now sympathetic and offered to help. What if the Warner Bros. animators contributed to the strike? It would be subversive and unexpected—perfect for the artists behind Looney Tunes.

That night, some of the loyalists held an emergency meeting at Abraham Lincoln High School. There was fear, resentment, and a desire to protect the studio. They planned a “back to work” effort intended to woo the strikers. Each loyalist there was given names of three strikers to approach with promises of reinstated bonuses.30 Starting the next day, many of the strikers and their families encountered a loyalist at their front door or on the other end of a telephone line asking them to stop associating with the “wrong crowd.”31

This one-to-three ratio indicates there were significantly more artists fighting for the Guild than were fighting against it.

Babbitt surely noticed that this offer to reinstate the previously withheld bonuses was a familiar strikebreaking tactic. It had been Gunther Lessing’s attempted strategy to win back the Disney cameramen from the IATSE.

As a leader of the strike, Babbitt’s days were packed from dawn until dusk. He was there for the mass picket line from 7:30 to 9:30 AM, chiding arriving loyalists either on the microphone or with the crowd. He contacted several labor groups affiliated with the AFL to spread support for a Disney boycott. He checked on the material that came from the publicity committee at strike headquarters. Each evening, when he wasn’t at the mass studio picket from 5:00 to 6:30 PM, he attended board meetings of other unions and appealed for support. His last task every evening was to plan for the following day with the other Screen Cartoonist Guild leaders, including Bill Littlejohn, Herb Sorrell, Dave Hilberman, and the head of the Warner Bros. unit, Chuck Jones.32

During the day, the publicity committee drafted flyers and bulletins to distribute to studios across Hollywood. Women typed drafts, men operated the printing press, and everyone had copies to hand out to non-strikers, industry professionals, and theatergoers.33 There were also “chalk-talk pickets” at theaters, in which strikers sketched on a portable chalkboard while they educated the public about their cause.34

The American Federation of Labor identified Disney as the only company in Hollywood not employing union labor. Littlejohn petitioned to other AFL unions, “Disney has long paid the lowest wages in the cartoon industry.”35 But there was a distinction between the company and Walt. Even Sorrell said, “The workers tried in every way to reach an amicable agreement but Gunther Lessing blocked their every move to make a satisfactory deal with the company.”36

The biggest blow came from the Technicolor film-processing plant. Disney had had a relationship with Technicolor since 1932. Beginning in 1936, Disney used Technicolor for all its films. That Thursday, Sorrell visited the Technicolor processing labs and met with the head of the laboratory technicians’ union. The technicians not only agreed to stop handling Disney film immediately, but they also threatened to strike if their managers forced the workers to handle a Disney film.37

On Monday, the Disney strike had galvanized the unions representing electrical workers, cameramen, maintenance men, air-conditioning men, teamsters, lab technicians, and culinary workers. The Screen Writers Guild donated $350 to the strikers. The Newspaper Guild at the Los Angeles Daily News refused to print the Donald Duck comic strip. After a speech from Babbitt to the Screen Office Employees Guild, the members voted to offer their complete support as well.

Just as George Bodle promised, pickets marched at movie theaters playing Disney films. Called “flying squadrons,” they got newfound public attention.38 Outside the Hollywood Pantages Theatre, actors Robert Taylor and Barbara Stanwyck talked to one of the strikers. The El Capitan Theatre, which was playing the new hit Citizen Kane, pulled the accompanying Disney cartoon almost immediately.

At the start of that week, the Labor Relations Board began to investigate the legitimacy of the American Society of Screen Cartoonists. The Disney company countered that the Guild signed up workers outside its jurisdiction, specifically from the studio comic strip, the Traffic Department (i.e., messenger boys), and the studio art school.

Strikers as “flying squadrons” picketing a theater showing Fantasia.

As the leader of the art school, Don Graham was torn between his allegiances. Quietly, he left Disney, never to return. Without Graham, the art school and training program both dissolved permanently. The pioneering education program that had elevated Disney animation—the heart of the Disney golden age itself—had come to an end.

Among the loyalists were artists who did not follow either Sorrell or the ASSC. One of these employees called the US Labor Department from inside the studio, begging for a conciliation between the Guild and the ASSC.39 A conciliator came on Monday, but on Tuesday, June 3, he said his hands were tied because Disney refused to recognize the Guild.

Those non-strikers wrote a petition that day, addressed to the president of the United States. Fifty-seven nonstriking artists signed the petition requesting the National Labor Relations Board to intervene. The signers included men and women from every department, like supervision (Jack King), concept design (Lee Blair) and story (Carl Barks). Not one of the names was a lead animator.40

Outside the gates, support for the Disney strike surged as the Screen Writers Guild, the Extras Advisory Council, and the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors joined the strike. With the additional pickets, Sorrell launched a nationwide campaign “to drive Fantasia from the screen.”41 Now Fantasia ticket-holders had to navigate through sixty to one hundred strikers at the theater.42

Though Fantasia was in its twenty-second week, it was still far from breaking even. Disney extended its national run with cheaper, mono-track screenings, but this angered ticket-buyers who paid extra for the “once in a lifetime” experience of Fantasound.43

The Reluctant Dragon was poised to bring in some much-needed income, once it was distributed to theaters on its June 6 schedule. But Sorrell met with Disney’s distribution company, RKO. With the Los Angeles Central Labor Council behind him, Sorrell threatened RKO with a boycott if it didn’t cease distributing Disney films during the strike. RKO deliberated. And with Technicolor striking in sympathy, The Reluctant Dragon’s release was postponed three more weeks.44