26 The Big Stick

One week into the strike, both sides were settling into their roles. The Disney strikers occupied the shady eucalyptus knoll opposite the studio’s front gate. Those who were not on picket duty relaxed there in the folding chairs, hammocks, and six camping tents that spotted the hill. The off-duty Disney strikers kept their morale high with ball games, horseshoes, Ping-Pong, badminton, chess, checkers, archery, and sketching. They called the knoll “Camp Cartoonist.”1

The non-strikers called it “Skunk Hollow.”2

Donations had been rolling in all week, but Thursday, June 5, saw the formation of a makeshift soup kitchen on the eucalyptus grove. It served three meals a day on long picnic tables, built by the carpenters at the Warner Bros. animation studio. The culinary workers’ union donated the services of a union chef, and for lunch served 511 hamburgers, 634 cups of coffee, and 29 pounds of coleslaw. “We served dinner at 6 o’clock after the mass picket line would go off, after the workers had gone through,” said Herb Sorrell. “And then the musicians many nights would send down a truckload of musicians and they would play and these kids would dance in the street in front of the gates.”3 When musicians weren’t available for the dance, the car radios sufficed.4

The spectacle was unlike any the press had ever seen. Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo dubbed it “Hollywood’s favorite strike.”5 Strikers rode donkeys and bicycles, donned roller skates, and dressed dogs with sandwich boards. Bill Littlejohn flew overhead in his biplane, a Luscombe Phantom two-seater, wiggling his wings above the strikers.6

On those long summer evenings, the strike community gathered on the knoll to hear announcements from Babbitt, Hilberman, Sorrell, and other leaders. Cheers and applause closed out each meeting.

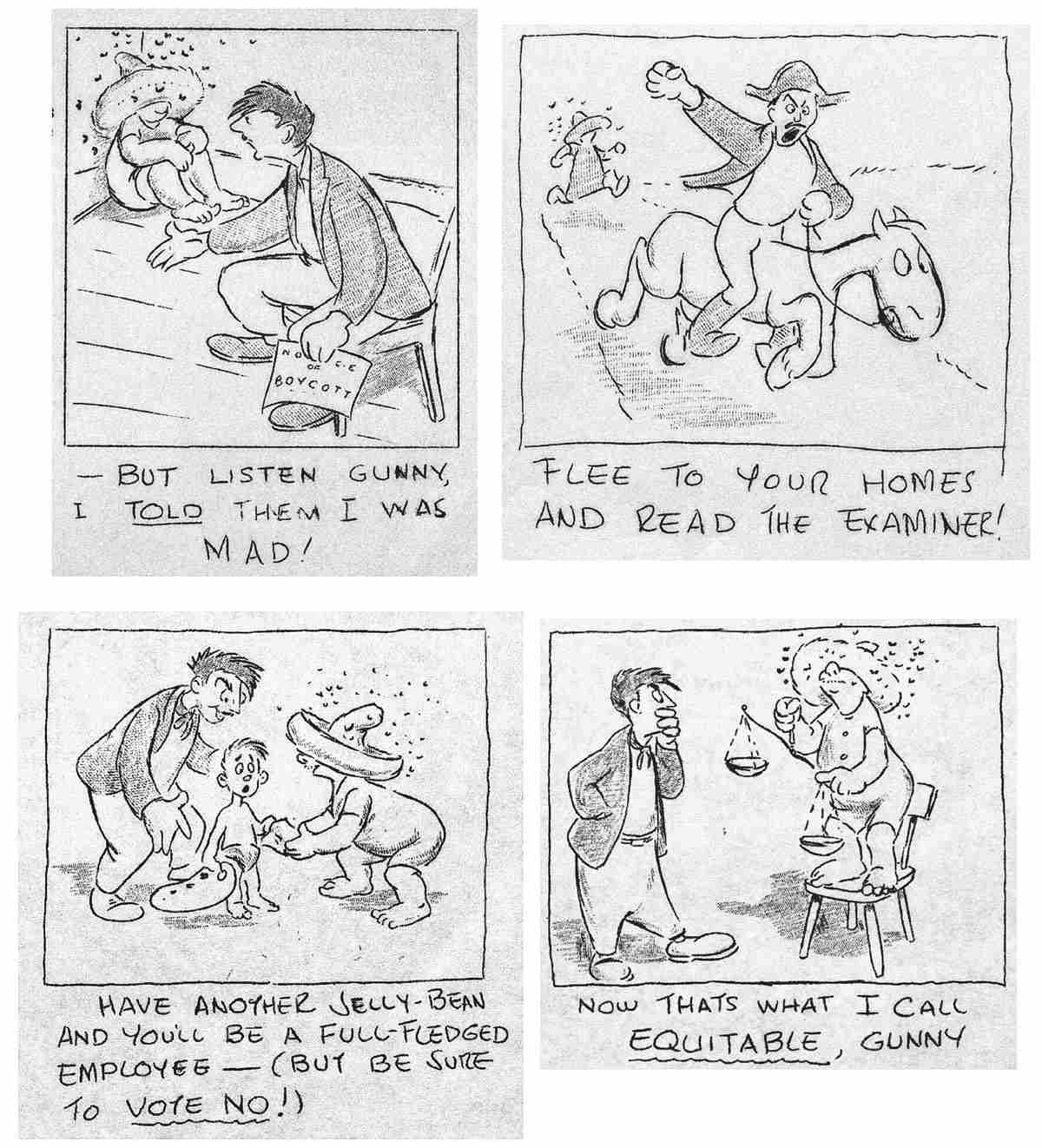

The strikers began receiving an internal daily newsletter called On the Line chronicling each day’s successes. The bottom always contained a single-panel cartoon caricaturing Walt beside a sombrero-wearing crony he called “Gunny.”

Drawings printed in the striker’s daily newsletter On the Line lampooning Walt and “Gunny”: (top, left to right) June 12, June 13, (bottom, left to right): June 18, June 20.

“Be sure and give Disney all the credit due to him,” Babbitt told the press. “The man had foresight and a certain genius and it took plenty of guts for him to buck this industry and prove he had the real thing. But other things are more important than what Walt had. When Disney began to get the idea for this Burbank studio, he became a different man. From a man who worked closely and collectively with his workers, he got to be boss. Since that time, the policy toward his employees—his studio despotism—has been—well, this strike tells you what it has been.”7

Leon Schlesinger made good on his promise. The Warner Bros. animators, led by Chuck Jones, took time at the end of each day to prepare for the Disney strike. Thursday, June 5, saw the Warner Bros. animators decked out as an American Revolution fife and drum corps blocking all traffic along Riverside Drive.

A handmade effigy of the strike’s true nemesis, Gunther Lessing, was hung from a eucalyptus tree, alongside another marked SCAB. Lessing addressed the strikers, requesting the effigy of himself for his office.8

Not every striker remained devoted to the Guild or its methods. Hank Ketcham, who would later create Dennis the Menace, was a young Disney striker early on. “As serious as the issues were, it all struck me as infantile behavior,” he remembered later. He chose to break ranks and return to work. “The loudest insults seemed to come from those whom I once considered my very good pals. It was a shattering experience for many; as in any civil war, the house was divided and close friendships evaporated.”9

One non-striker counted more than thirty-five Disney strikers coming back to work. Babbitt’s rancor didn’t help matters. Several strikers used the microphone with the portable PA system, but only Babbitt was poised in verbal attack mode. His behavior echoed a description of his mother: “If she had it in for you, God help you.”10

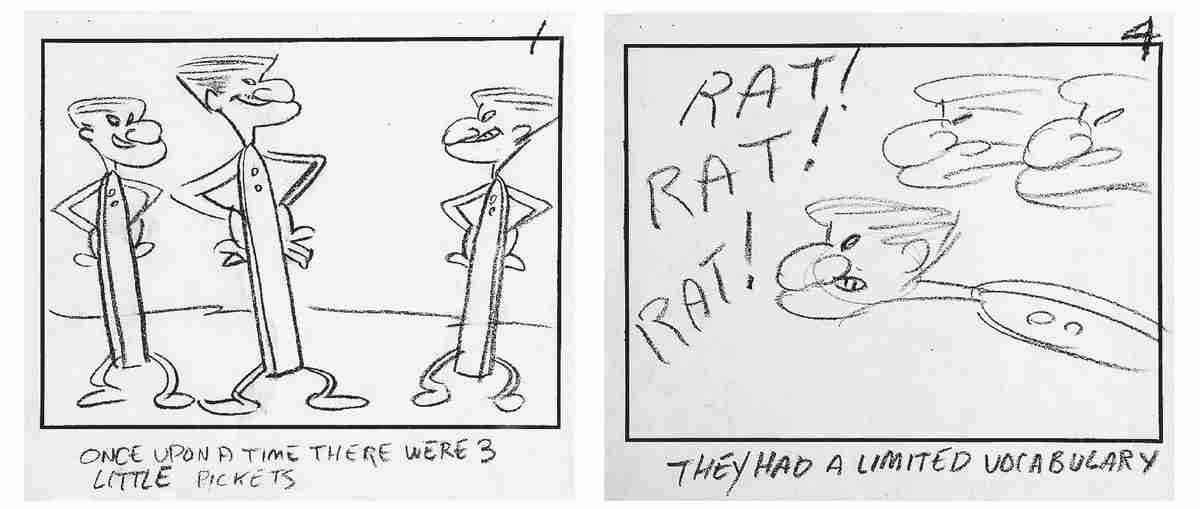

“Heard that this morning Babbitt, microphone in hand, called everybody a big gray rat,” one non-striker wrote. “Didn’t sit well with those within and without. Bad taste. More guys back today.”11 If so, a roughly equal number must have joined. According to records, the number of strikers always stayed around 330.12

Disney studio gag drawings of Art Babbitt on strike, by nonstriking artist Jesse Marsh.

Sometimes Babbitt wished the non-strikers each a loud and sarcastic “Good morning” by name, hoping to shame them. “Well here comes Milt Kahl,” shouted Babbitt one morning. “His wife has to protect him by bringing him to work. Poor Milt!” Mrs. Kahl dropped off her husband, drove back around and returned fire at Babbitt, “You can’t even keep a wife to protect you!”13

Wives on both sides appeared ever supportive of their husbands. Word got out that wives of loyalists joined their husbands crossing the picket line and helped with work in the studio, pro bono.14 The wives of the strikers, on the other hand, formed a committee called the Women’s Auxiliary and began organizing fundraisers, starting with a bake sale.

Bill Tytla remained with the strikers, without his wife, Adrienne. His presence on the knoll and at meetings held weight. Adrienne recalled, “There were phone calls, excited conversations, long meetings, bitter disappointment.” When Tytla drove back to his home after a long day, he had to contend with a wife recovering from tuberculosis who was barely mobile. The two also had a young son, and Tytla had gone from being one of the highest-paid animators in the world to earning nothing. Adrienne sorely needed health care and childcare and could only feel “torn and ambivalent” about the strike.15

The strike leaders were also concerned. Faith in their cause was only as strong as the group’s conviction, and cracks were starting to show. Artists who were friends on opposite sides talked through the studio fence. This was vehemently discouraged, and the strikers’ newsletter didn’t mince words. “Those who have remained inside have been constantly bombarded with misinformation and false promises. . . . DON’T LET THOSE WHO HAVE BEEN FOOLED TRY TO FOOL YOU !!!”16

The Los Angeles Central Labor Council, which was affiliated with the AFL, was trying its best to mediate. Now the council was prepared to finally place Disney on the Unfair/Do Not Patronize list. This potential boycott would be enforced by five million AFL members nationwide. Walt saw this as nothing more than a bullying tactic, waving a threat over his head like a wooden club.

The council committee consisted of president Harry Sherman, executive secretary-treasurer J. W. Buzzell, and representative Lew Blix. Walt agreed to an initial meeting with the council committee on Tuesday, June 10. Walt repeated his demand for a secret election to determine the winning union. The council demanded a cross-check—a name-by-name comparison between the lists of Guild members and Disney employees. Nobody budged.

Walt had a second meeting with the council in his office on Wednesday, June 11, the fifteenth day of the strike. With him were Roy and Gunther Lessing. There were also four strikers who had not yet stoked Walt’s ire, as well as a secretary transcribing verbatim.

J. W. Buzzell, executive secretary-treasurer of the Los Angeles Central Labor Council, in 1940.

“Mr. Disney,” began Buzzell, “the fact that there is a strike here and a petition to put the firm and its products on the official Unfair list for the labor movement, under our law we are required to make every possible effort to reach an amicable, acceptable settlement of the difficulties before we take that kind of action.”

“I think we have given you our answer before on that, Mr. Buzzell,” said Walt. “We are just back where we were when we first started to negotiate.”

“It’s probably true,” said Buzzell. “Our purpose in making this visit is to attempt to see if we can’t change your mind.”

“To me,” said Walt, “it’s the guy with the big stick standing there, trying to make me change my mind. No other way to look at it. No other answer to it. To be very frank, with me you will agree on that, won’t you?”

“I will agree that unless you do it, we are going forward with [the boycott],” said Buzzell, “and there isn’t anything the Labor Council can do except to say to these people we’ll go as far as we can. It is not our desire. We’d rather settle things than fight. But we have to.”

“As long as the big stick settles it,” said Walt, incredulously. “Conditions are not going to improve by the moves that you think are your weapons. But if that’s what it must be, that’s what it must be, and I fought for principles before, and I’ll fight for them again. I have never been yellow—I have never been a coward. I might have been foolish at times, but I sort of have a faith, a faith that kind of pulls you through a lot of these things. When it comes to a compromise of this sort, to me it isn’t a compromise. It’s just laying down. To me it’s one of the most un-American things that can be done.”

Walt continued, “It happens to be, in my opinion, a minority that’s claiming the right to bargain. Now what they are after is the truth, and that’s what we have got to find—the truth of the thing. Who is the majority? In a case of that sort, it should be determined in the proper way . . . and you want to take the big stick and beat them into thinking your way.”

The strikers boiled it down to the one thing they needed. “You simply say we have a majority,” one said.

“The cross-check is definitely unfair,” said Walt. “People have signed your cards under pressure.”

“That’s your opinion, Walt,” said another striker. “We don’t believe that.”

“I have a right to my opinions just as you have to your opinions,” said Walt. “The one way to really find out—the one way to prove it—is to put it up for a vote. And the very fact that you refuse to go to a vote just convinces me that you haven’t got a majority. And for that reason I will fight all the harder on the thing—”

Buzzell replied, “I’m not saying we’re doing it for the purpose of making threats. . . . It is the natural course of events, and if we do it, we shall endeavor like any other fight. If we have to fight, we’re going to throw all the punches we can, and duck all we can, and kick when we can.”

This analogy confirmed the deeply held suspicions that Walt had been harboring since he was a boy. “I know the usual union methods, Mr. Buzzell,” Walt said. “I’ve been brought up through my life with them. My dad was beat up by a bunch of union people one time.” Walt’s emotional inner child—that remarkable insight that produced masterpieces of family entertainment—was now navigating union negotiations.

Lessing heard the boxing metaphor and played to Walt’s fears, saying to Walt, “It must mean that they attempt to carry out the threat to turn this studio into a dust bowl or a hospital.”

“I don’t see anything unfair about a cross-check,” said a striker. “I’d say so many people signed Guild cards—they must have signed them because they wanted to belong to the Guild.”

“What is unfair about a secret election?” asked Lessing.

“I think if we held an election it would still exist under that condition of coercion,” said the striker. “Walt points out they will go in and vote secretly. A lot of people even in a secret vote both haven’t the guts to vote the way they want to.”

“The only coercion I know is that the Guild has threatened them,” said Lessing. “I never pass the picket line without somebody either taking my picture or my name.”

“It’s not the union or things like that that we are fighting,” said Walt, “it’s the methods of determining who should be that bargaining agent.”

“You’re asking us to submit to an election,” finished Buzzell. “There’s five or six very valid reasons why we don’t. I presume you have played poker. If you’ve brought a hand and showed your hand, you wouldn’t submit to dealing the cards over again to find out if you had it right. And we ain’t going to either. That’s what it amounts to.”17

That was that. At noon the next day, the Central Labor Council officially placed Disney on the Unfair/Do Not Patronize list. The nationwide Disney boycott had begun.

On Thursday afternoon, June 12, nearly all the loyalists ditched work early to avoid the strikers. When the picket line surged again at 5:00, the street was almost empty, except for a small group.18 They were dispersed by a parade of marching Warner Bros. animators, this time with costumes and props à la the French Revolution. Several of them dressed like executioners and carried a hand-crafted guillotine on their shoulders. On it lay the effigy of Gunther Lessing, its neck under the blade beneath a sign reading, SEVERANCE PAY OR SEVERING HEADS? Others carried the sign bearing the adapted French battle cry, “LIBERTÉ, FRATERNITÉ, CLOSED SHOPPÉ.”19

Support for the strikers had grown. The Los Angeles Herald Express had pulled the Mickey Mouse comic strip, and telegrams of encouragement came in from the newspaper guilds of Cleveland and San Francisco. The publishing union, Allied Printing Trades, refused to publish Disney comic books. Cash donations kept rolling in.

Some of the nonstriking inkers and painters, tired of being harangued by the striker horde, sneaked into work though the studio’s storm drain. The strikers got wind of this and gleefully called them “sewer rats.”20

The feelings about Walt varied among the strikers.21 Some of them maintained no ill will against the company. Others, like Babbitt, spoke with histrionics, radicalizing the strike into a class war. Walt would learn just how hot the blood ran.

On the morning of Friday, June 13, Walt Disney met with the labor relations council for the Motion Picture Producers Association, Pat Casey. The meeting was as fruitless as the others. “Another appeal to reason terminated in a deadlock as a result of the now well-known Disney stubbornness,” blasted the strike bulletin.22 In the afternoon, the company prepared for a press screening of The Reluctant Dragon on the studio grounds. When the journalists arrived, they were blocked by a massive demonstration, as one of the strikers improvised a “Man on the Street” radio program over the PA microphone.

Walt was not about to give the strikers any more fuel for their demonstrations. Like the day before, he dismissed his employees early, this time to reconvene for a staff meeting at the high school auditorium. The loyalists were all gone by the time the evening pickets assembled.

When the strikers learned where the loyalists had gone, they moved to the high school, sound truck and all. By the time the strikers arrived, many of the loyalists were already heading home. Walt was pleased with having won this battle. He sat in his blue Packard convertible and smiled, tipping his hat like President Roosevelt.

Babbitt grabbed the microphone and roared from the sound truck’s loudspeaker, “Walt Disney, you ought to be ashamed.” He said it again, emphatically: “Walt Disney, you ought to be ashamed!”23

Babbitt ran down while Walt stopped and got out of his car. As Walt’s feet hit the pavement he clenched his fists. “Why you dirty sonofabitch!” shouted Walt. Hundreds of voices booed and cheered. The crowds closed in on them. Before either man could take a swing, Babbitt was pulled away. Walt saw this, got back into his car, and drove off.24